There is a lot of loose talk about the proverbial “algorithm” these days, and you can thank Netflix for much of it. In the mid-2000s, when it was still just a DVD rental service (and a similarly minded company like Spotify was still years away from launching), Netflix was already tuning proprietary software that went through customers’ viewing habits with a fine-tooth comb, trying to predict what movies they’d want to watch next. The streaming era brought a wealth of new data with it, allowing Netflix to turn that comb into an atomic microscope. By 2013, after they’d finally pulled the plug on the DVD business and also begun moving into producing original programming, Netflix engineers told Wired that they could track users’ “different viewing behavior depending on the day of the week, the time of day, the device, and sometimes even the location,” as well as when they “pause, rewind and fast forward” in a given program.

That year saw the premiere of House of Cards, the first original series produced exclusively for Netflix. (Today, users may forget their first foray into TV production: 2012’s misbegotten comedy-thriller Lillyhammer, featuring Little Stevie Van Zandt as a gangster in witness protection, which made in collaboration with Norwegian television.) Today, House of Cards stands as perhaps the most important television show of the 2010s. It was, for one thing, the second show ever (again, we are forced to account for Lillyhammer) to release all of its episodes at once. The ritual of binge-watching itself became a part of the selling point. Also, Netflix claimed that it based its decision to buy David Fincher’s political drama on the same user data that was powering its recommendations—an elaborate system of microtargeting that made old-school practices like focus groups and ratings analysis look primitive by comparison.

According to a report from the New York Times after the premiere of House of Cards’ first season, Netflix agreed to produce the show after it determined that Fincher’s films were especially popular on their service, as were movies starring Kevin Spacey (remember those days?) and British TV thrillers like the original House of Cards. Everything about the show made it a sound investment for Netflix—a sure enough bet that the service reportedly ordered two seasons of the series up front, without even watching a pilot, and shelled out $100 million for the privilege. The move was unprecedented at the time, but today, we are inundated with products that seem reverse-engineered to fulfill existing algorithmic niches and resonate with popular keywords: from uncannily targeted print-on-demand t-shirts for mothers who listen to Iron Maiden and were born in August to Netflix’s own Stranger Things, which is hard to imagine existing without known market demands for ‘80s nostalgia, alien stories, and Spielberg-eque shots of kids on bikes.

Not everyone in the industry was on board. “Data can only tell you what people have liked before, not what they don’t know they are going to like in the future,” FX president John Landgraf commented to the Times in their report. “A good high-end programmer’s job is to find the white spaces in our collective psyche that aren’t filled by an existing television show.” History’s great television shows, he argued, were created “in a black box that data can never penetrate.” But House of Cards proved Landgraf’s theory wrong, at least in terms of public engagement. Thanks to (or in spite of) its subtlety-free high melodrama and protagonist Frank Underwood’s Batman-villain antics, the show was instantly popular, and remained so across five more seasons, even as it buckled under the weight of its own self-seriousness and scrambled awkwardly to a conclusion following the public disgrace of its star actor. Its commercial success spurred a complete repositioning of Netflix’s role in the industry, helping the company to grow drastically and driving it to exponentially increase its original offerings. In 2015, Netflix produced Beasts of the Southern Wild, the first of hundreds of feature films. The company broadened its service to international markets in 2016, and was available in 190 countries by 2018. That year, it spent $8 billion on a proposed slate of 700 series and 80 original films.

Now, six years after House of Cards premiered, everyone in the television business is trying to be Netflix. Networks and corporations from Amazon to Epix to YouTube to (most recently) Apple are trying to compete by producing their own top-shelf original programming, and mounting video streaming subscription services to put their exclusive IP behind a paywall. Companies face a creative quandary: balancing the seemingly boundless demand for creative new programming with their natural instincts toward conservative, fiscally defensible business decisions. Netflix found success by attempting to solve this problem with data analysis, but not all companies have access to the algorithm they’ve developed for over a decade. Other corporations use whatever techniques they can to determine what expensive star-studded programming is a “safe” bet. (Amazon made its foray into original programming by having viewers vote on their favorites among a collection of pilots to determine which be produced.) With even Netflix running up billions of dollars in debt every year, one wonders how much money television producers—and streaming services, especially—will throw at the wall before the bubble bursts.

On Spin’s staff list of television picks from the 2010s, we privileged shows that spoke to the more utopian possibilities of the Wild West period, rather just House-of-Cards-level commercial triumphs. In an industry where anything seems possible, the anomalies—the weird niche programming we find deep in our recommendations queue—feel as emblematic of the era as the zeitgeist successes. As we noted back in a 2016 year-end essay about the state of television, the TV and video streaming-industrial complex is becoming more and more like the modern Internet as a whole. Theoretically, it should be a place where anything is possible, with endless opportunities for strange and individual visions to find audiences, but the field is still largely defined and controlled by the whims of just a few corporations.

There’s only so much critiquing we can do of the cynical race for TV eyeballs without acknowledging our own similar motivating factors. We hope that this list of the 30 shows that mattered most to Spin staffers this decade (we limited this to series that premiered no earlier than 2009, Mad Men and Breaking Bad fans) provides some enlightening or at least interesting perspective. But we can also call it what it is: a flashy piece of content produced by a mid-sized online media company that—like the Netflixes and Epixes of the world—is also in constant need of devising new ways to get through to its perceived audience and keep them coming back for more. Throw us a bone and read on below.

See also: 30 Great Movies That Defined the 2010s

RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009-present)

Everything ever written about RuPaul’s Drag Race is true. There is perhaps no show on this list as holistically successful as this one, which has enriched its participants and our society in different but equal measures. As the decade concludes, drag culture has been pulled from gay clubs squarely into the mainstream, giving a whole generation of teenagers—and adult pop stars—a refreshingly diverse new set of idols to pattern themselves after. World of Wonder, the bootstrapped production company behind Drag Race, is now a cottage industry unto itself, producing a constant stream of shows, live tours, conferences, and, as a result, millionaires. Real Drag Race heads will encourage you to dive into Drag Race Thailand, available to watch only on World of Wonder’s streaming app, WOW Presents Plus, which also features myriad original series from Drag Race contestants.

RuPaul embarked on the endeavor of turning drag queens into crossover superstars decades ago, and it certainly could not have been an easy road. Drag Race has elevated him to pop culture royalty, but it came after decades in the figurative wilderness. RuPaul’s personal triumph, like that of his little-show-that-could, is also a societal one, but all the righteous good feelings about Drag Race can obscure the fact that it became a sensation not just because of its cultural timing, but primarily because it’s insanely good television. It turned out, after all those years, that the best vehicle to convey the totality of drag—the performances, fashion, slang, camaraderie, and community—was not music, or movies, or even the stage; it was, instead, a competition show that requires queens to sing, dance, act, joke, sew, and walk the runway, in the process peeling back the curtain to show the blood, sweat, tears, and shade of it all. One could say plenty about everything reality television has wrought; but for this show alone, it was worth it. —JORDAN SARGENT

Parks and Recreation (2009-2015)

Nearly fifteen years after its premiere, it’s hard to understate the influence of NBC’s The Office on television comedy. The American adaptation of the British series of the same name mapped the screwball sensibilities of Christopher Guest’s mockumentaries and Monty Python onto a story about white-collar bureaucracy at an inherently banal paper company in Pennsylvania. From its deadpan interviews and low-budget production to its often impressive commitment to unflinchingly specific bits, the show rethought foundational assumptions about the sight and sound of the primetime sitcom, stretching the possibilities of an endlessly familiar workplace setting to their limits in pursuit of an unexpected laugh.

As its closest successor among a number of NBC offshoots, Parks & Recreation built on the success of The Office’s handheld, faux-vérité style, trading one form of agonizing middle-management ennui for another. SNL alum Amy Poehler plays Leslie Knope, the deputy director of Pawnee, Indiana’s Parks and Recreations Department; joined by a cast of then-rising stars including Aziz Ansari, Chris Pratt, and Aubrey Plaza, Poehler’s character constantly subjects herself to the most demeaning aspects of being a local government official in her clumsy attempts to climb the ranks of local government. Like many comedies before it, the series plays up all the worst qualities of its transparently flawed characters, riding the ups and downs of an office full of brain-damaged narcissists and their futile attempts to affect change in their community.

While there’s an inherently political dimension to any show about local government, the series largely shies away from meatier questions about partisanship, keeping it light with a focus on civic inefficiency. In season two, when Pawnee faces a government shutdown amid what’s implied to be the 2008 financial crisis, the characters largely shrug off what could be a compelling look at the political process. Even the show’s most ideologically consistent character Ron Swanson (Nick Offerman) rarely escapes his own myopia, ending each episode steeped in the same bullish delusions that he had at its beginning. Such is the glue of nearly every primetime sitcom since Seinfeld, but despite it all, Parks & Recreation remained one of the funniest and most comedies on the small screen in this decade. —ROB ARCAND

Teen Mom (2009-2012; 2015-present)

Say what you will about the artistic merit of MTV’s long-running teen parenthood docuseries franchise, which was birthed after the launch of 16 and Pregnant in 2009, but it seems to have had an important real-world impact. Naysayers might argue that these shows glamorize teen pregnancy, but studies have shown that the opposite seems to be true. One such report, published in 2014 by Wellesley College economist Philip Levin and University of Maryland economist Melissa Kearney, theorized that Teen Mom and 16 and Pregnant could be partially credited for a dip in the teen birth rate that occurred over its first year and a half on the air.

Beyond inspiring teens to use contraception by showing the difficulties of being a young parent, MTV’s franchise has been a major force in television culture throughout the 2010s. After the success of Teen Mom OG, MTV launched Teen Mom 2, Teen Mom 3, Young and Pregnant, Young Moms Club, and multiple standalone specials, including one about abortion. Across the pond, there’s MTV UK’s Teen Mum, and even a Teen Mom Australia. TLC also got into the game in 2012 with High School Moms, then launched Unexpected in 2017.

There’s a reason why MTV’s franchise has been so successful: The unscripted drama is hopelessly addictive. OG and TM2 stars Maci Bookout, Catelynn Lowell, Amber Portwood, Chelsea Houska, Kailyn Lowry, and Leah Messer, along with former subjects (and trainwrecks) Farrah Abraham and Jenelle Evans have since become reality stars and tabloid fodder. Stories about the cast members’ most private moments—weddings, splits, pregnancies, miscarriages, feuds, arrests, custody battles, drug issues—appear frequently in anything from celebrity and gossip magazines to prestigious national publications. After the news cycle, viewers then see the events play out on the shows, which often have cameras capturing these news-making moments as they happen, with the film crew also breaking down the fourth wall to provide a glimpse into how decade-long storylines survive and become appointment TV.

The longevity of the Teen Mom franchise means that none of the girls are actually financially struggling or teens anymore, but their tales still serve a double-pronged purpose: entertaining viewers with unsparing character studies and educating them about the trials and tribulations of teen parenthood. —ANNA CHAN

Game of Thrones (2011-2019)

People forget that Game of Thrones used to be good. Back before the stray Starbucks cups, the Bam Margera lookalikes, and the nonsensical, would-be poetic plot twists, it reimagined big-budget TV both in its scope and substance. Couched in pseudo-medieval fantasy plotlines, the series and the books it drew from thoughtfully explored the dynamics of power and politics. Thrones raised the bar set by Peter Jackson with his adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings nearly ten years earlier in creating a richly symbolic universe with a popular appeal that drew in fans far beyond the ranks of genre fiction obsessives.

The story begins simply, with knight-hero Ned Stark riding south to stake a claim for his family in the continent’s capital. To the East, the last survivors of a once-great royal family are plotting their eventual return from exile. In the far North, whispers of an ancient evil are exchanged among rangers of an order known as the Night’s Watch. From there, the narrative branches off in countless, disparate directions. Some plotlines are only tangentially related to the core themes established in episode one. These strands might be drawn out for five seasons without resolution, or be cut off prematurely after a few episodes with minimal fanfare. Traditional narrative structure was never important to showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, but that helped make the show compelling and, inevitably, surprising.

Beyond the pulpy maximalism of its source material, the show’s greatest strength has always been its acting. The books were told from multiple points of view, building readers’ investment in characters over time, and modulating perspectives to allow for a healthy dose of dramatic irony. Without the benefit of shifting lenses, the heavy lifting in the final seasons of the show was done by its cast, many of whom delivered some of the decade’s great TV performances. Even in the last season, when the show’s story surpassed the still-unfinished book series and took a turn for the ridiculous, Liam Cunningham, Gwendoline Christie, Peter Dinklage, and, in particular, Alfie Allen, outshined the increasingly disappointing scripts. Minor characters, too, were assets at different points throughout the show’s run—think of Kate Dickie’s Lysa Arryn and Pedro Pascal’s Obyern Martell, in the role that gave him a career.

Standout acting anchored the series’ most ambitious moments, from the Battle of the Blackwater to the Red and Purple Weddings. In these scenes and many more, GoT established itself as the most technically masterful show on television, with shots costing millions of dollars and production crews numbering in the thousands. An entire documentary covering production of the eighth season, with its unprecedented $90 million budget, demonstrates how much work went into making the show’s world as immersive as it is. Though it was visually dazzling until the end, the show eventually undermined its central themes, morphing into something too grandiose to be controlled. But before it lost sight of the power struggles and plot twists that made it great, Game of Thrones was a genuinely revolutionary 21st-century epic: fantasy elevated to the level of high drama, and television made on a Hollywood scale. —WILL GOTTSEGEN

Read our 2019 retrospective essay, “A Requiem for Game of Thrones” here, and the rest of our GoT coverage here.

Girls (2012-2017)

Depending on your personal tolerance for Lena Dunham’s insular take on post-collegiate life in the big city, the initial “voice of her generation” headlines that came in Girls’s wake may or may not have seemed warranted. (“Or at least a voice. Of a generation,” Dunham joked during the pilot.) But it’s hard to contest the point that there was no true analog for her NYC-based millennial dramedy Girls on television when it aired. There were also not many young showrunners with limited small-screen bonafides getting that level of professional opportunity, let alone female ones—let alone with as much creative carte blanche as Dunham clearly had. The TV industry had not yet inflated into a leviathanic balloon where any piece of vaguely enticing intellectual property could get a writer a foot in the door.

HBO and producer Judd Apatow took a leap of faith by allowing Dunham, a 25-year-old writer and director with only one niche indie film to her name, to helm a series. It paid off. If you were looking to reduce Girls to a simplistic tagline, it would be easy to describe it as Sex in the City for people born in the late 1980s, with with Hannah (Dunham), Marnie (Allison Williams), Jessa (Jemima Kirke), and Shoshana (Zosia Mamet) defining the categories that viewers could place themselves into. These characters had a classic-sitcom je ne sais quoi about them that made it easy to follow their bleak and ribald capers, whether you found them to be relatable, or detestable, or sociologically fascinating, or all three.

But Dunham pushed the limits of her familiar ensemble-comedy frame, exploring extreme bedroom realism and weighty plotlines about substance abuse, depression, and sexual coercion. In later seasons, Girls experimented with bottle episodes and elliptical plot lines; episodes ceased to flow into one another in the manner of a normal serial show, or remain discretely episodic. (At the same time, Louis C.K., who was then frequently spoken about in the same breadth as Dunham, was engaging in formally similar but much less ideologically progressive experiments on Louie.) Dunham’s polarizing series ran for six seasons despite modest and declining ratings, following an unstable trajectory shaped by its own miscalculations. Strangely, the worst ideas on Girls—say, season two’s half-baked Donald Glover arc, seemingly carroted in due to criticism of the show’s near-total lack of people of color—helped it remain close to the zeitgeist. Its missteps and unexpected triumphs were perfectly suited to a changing internet that was just starting to turn toward TV recap content and politicized debates about pop culture on platforms like Twitter.

The influence of Girls on today’s TV landscape is massive. There are plenty of shows that might not have been greenlit at all without Dunham’s series paving the way for uncompromising television about the lives of anti-heroic women and millennials more generally, from Broad City to You’re the Worst to Difficult People to Fleabag and beyond. As Crazy Ex-Girlfriend’s showrunner and creator Aline Brosh McKenna put it to Vulture in 2016: “A lot of the things we’ve done we wouldn’t have been able to do without Lena.” —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Veep (2012-2019)

It’s easy to forget that Veep is a remake—at least, kind of. Creator Armando Ianucci adapted the HBO political comedy series from The Thick of It, his viciously funny mid-aughts satire of the backbiting bureaucracy of the British government. Like its English forebearer, Veep offers a refreshing, if demoralizing, view of the inner workings of the White House and Capitol Hill. In this way, it diverges meaningfully from over-earnest and milquetoast fairy tales like The West Wing, and forms an absurdist counterpoint to the Machiavellian cloak-and-dagger operations in House of Cards.

Like Frank Underwood and his amoral allies, Vice President Selina Meyer (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) and her underlings’ self-interest supersedes any genuine investment in the well-being of the American people. Unlike in House of Cards, though, Veep’s characters aren’t brilliant and connected backroom operators tossing journalists off train platforms and thinking twelve steps ahead of their enemies. Instead, the government officials foregrounded in the Veep universe are portrayed as petty Capitol Hill lanyard-wearers, middle aged burnouts, and schlubby men in baggy suits whose senses of dignity were surgically removed the moment they stepped inside the Beltway. Meyer’s rank-and-file desk jockeys spew bile and call each other things like “Frankenstein’s Monster, if his monster was made entirely of dead dicks.” Any would-be shrewd power play turns into a comedy of errors where the fabulists, careerists, grifters, and—in Jonah Ryan’s case—dipshits routinely trip over their own egos.

Some of the best comedic moments in the show stem from Louis-Dreyfuss’s character being unable to hide her revulsion while interacting with the regular folk she ostensibly sought higher office to serve. In the pilot episode, Meyer cynically refers to a photo op with constituents as an opportunity “to meet some regular normals,” and then spends those meet-and-greets either awkwardly fumbling for conversation, passive-aggressively insulting everyone, and feigning a comically strained smile. (In a particularly resonant moment in the Season 3 premiere, Meyer pretends to be impressed when a woman at a book-signing brings her an unsolicited butter sculpture in the shape of Iowa.) Veep panders to our sinking suspicion that the people who have sworn to look out for our best interests only care about advancing their own. Luckily, the staggering volume of surgically well-crafted jokes packed into each 30-minute episode offsets the grimness of that implication. —MAGGIE SEROTA

The Mind of a Chef (2012-2017)

Aside from memes and the destruction of several industries, millennials’ greatest cultural contribution may be the cultivation of an explosion in riveting television programming about food. By the end of the decade, Netflix would provide a couple of bloated and excessive capstones in the form of Chef’s Table, an overwrought documentary series that treats modern cooking with reverence normally applied to renaissance art, and Final Table, a show where 12 acclaimed chefs from around the world cook rare and expensive ingredients in a ridiculous thunderdome of a studio for no prize money at all. Instead, the winners simply receive the satisfaction of having triumphed in Netflix’s grand cooking competition. The implication is that the competition is so pure that the chefs don’t even care about cash, but the subtext is that an acknowledgement from TV’s new kingmaker is worth more than any dollar amount. Watching this insane spectacle with an even baseline knowledge of the ways in which global food production exacerbates global warming and environmental destruction makes it feel even more ridiculous—the cooking contest we didn’t ask for but most definitely deserve.

The revolution in food TV was spearheaded, of course, by Anthony Bourdain, whose groundbreaking No Reservations series premiered in 2005. Along with hosting nine seasons of the show, Bourdain would produce several spin-offs and offshoots before moving to CNN in 2013 to begin Parts Unknown, a show that leaned even more heavily on the political consciousness that made No Reservations feel so radical in the first place. But for my money, Bourdain’s most purely enjoyable show is one that he executive produced but appears in only as a disembodied narrator: The Mind of a Chef, a PBS program that debuted in 2012. Where Bourdain’s earlier work expanded the idea of what food TV could be, The Mind of a Chef is a far more simple and humble endeavor that ties his travelogue style to the genre’s early beginnings in shows like Julia Child’s The French Chef.

Which is to say that on The Mind of a Chef, well-known cooks like David Chang (Momofuku), Sean Brock (Husk), and April Bloomfield (then of The Spotted Pig) mostly stand before you in the kitchens of their restaurants and make dishes. This is the primary appeal of the show: the simple pleasure of learning about technique and ingredients, and of seeing great food made in front of you step-by-step. But this is a documentary series, too, and over the course of each season the chefs begin to peel back the layers of influence behind their cooking, venturing out of the cocoons that are their restaurants in order to dig up the roots of their inspirations. Brock, for instance, travels to Senegal to trace the history of dishes from the low country of South Carolina, a state that was originally built on the backs of West African slaves; Gabrielle Hamilton, chef at the fantastic New York bistro Prune, escapes to Rome, where she compares ravioli recipes with an elderly Italian woman, in the process crashing headlong into cultural differences regarding feminism. Bourdain was behind far more celebrated programs than The Mind of a Chef, but it is here where you can most easily see his essence—the show was clearly created and nurtured by a generous and optimistic soul, one who loved good food and wanted it to be celebrated, and truly understood, by the world. —JORDAN SARGENT

On Cinema (2012-present)

When On Cinema began as an unlikely web series near the beginning of the decade, it seemed like just another of Tim Heidecker’s countless short-lived side projects, sure to end up buried among YouTube-only gems like his Comedians in Cars Getting Comedy parody, his cooking show, or his Coca-Cola standup routine. On Cinema, however, would progress a long way from its initial premise as a banal Siskel-and-Ebert-style review show where Heidecker and his cohost Gregg Turkington (best known as his anti-comedian persona Neil Hamburger) rated films they clearly hadn’t seen. Playing warped fictional versions of themselves, the two comedians gradually began using On Cinema to stage a surreal battle of the egos, sprouting from the Turkington character’s staunch commitment to keeping the show focused on the movies, and the Heidecker character’s insistence on discussing his personal life and promoting various music projects and short-lived entrepreneurial schemes.

This ongoing struggle culminated with Heidecker being charged with murder for selling faulty vapes that killed 20 people at an electronic music festival. Adult Swim subsequently posted a full five-part trial, featuring exhaustive attention to the formal tedium of legal proceedings and little in the way conventional jokes. That willingness to take a patently silly setup to its most elaborate possible conclusion is the norm for On Cinema, a show that has now spawned live tours; a yearly Oscar special; an entire book (and an exhaustive Vulture reference manual) devoted to its complex mythology; the secret-agent spoof Decker, an entirely separate Adult Swim series supposedly conceived by Heidecker’s On Cinema alter ego; and, most recently, a feature film. Taken all together—and with thanks to Cartoon Network’s admirable tolerance for Heidecker and Turkington’s high-conept antics—the On Cinema universe has transcended its humble beginnings, becoming the most ambitious avant-comedy experiment in recent memory. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Vanderpump Rules (2013-present)

An offshoot of one of the predominant reality TV franchises of the 21st century, Vanderpump Rules follows a group of aspiring models, actors, and musicians who are paying their bills by working in a Los Angeles restaurant owned by Lisa Vanderpump, a former Real Housewife of Beverly Hills. These people clearly want to be celebrities, and in some sense, they’ve made it: it’s just that they’re famous now for their status as fame-seekers on the show, forever condemned to a limbo of playing themselves at the day job that was supposed to briefly support them on the way to some other, ostensibly more substantive, form of stardom. Reasonable people might view this outcome as some sort of hellish paradox—the result of a wish on a cursed monkey’s paw. But the men and women of Vanderpump Rules are not reasonable people. They seem quite happy with the way things have worked out.

Their onscreen adventures generally involve drinking too much, sleeping with each other’s partners, publicly accusing each other of sleeping with each other’s partners, and—in the case of DJ James “White Kanye” Kennedy—constantly getting fired. The self-absorbed drama and petty narcissism of a bunch of service workers with showbiz ambitions isn’t unique in and of itself; any current or former restaurant employee is familiar with the sort of sexual musical chairs that can go on between staffers. But there’s something transfixing about this particular bunch of vapid freaks—the way they make the same mistakes over and over again, but show just enough growth to delude you into thinking they may someday get their shit together.

Perhaps unintentionally, Vanderpump Rules more vividly illustrates the insane ouroboros of this decade’s attention economy than most things on TV. But the genuinely compelling interpersonal drama, and occasional moments of unexpected sympathy, make it more than that, too. These people may be drunk shitheads, but they’re our drunk shitheads. —MAGGIE SEROTA

The Americans (2013-2018)

When the possibility of collusion between the Trump campaign and the Russian government—give or take a piss tape—became the biggest news story in the country in 2016, The Americans still had two more seasons to run. Russian covert operations of the sort depicted on AMC’s Cold War spy drama had once again become a point of popular interest, and the show could have easily turned itself into a heavy-handed allegory for the Trump era. Fortunately for viewers, it stuck with the precision-crafted plot arcs its writers had already planned out. “We try to stay in a bubble because we don’t want anybody to ever feel like the people doing this show are watching current events,” series creator Joe Weisberg told The Hollywood Reporter in 2017. Nonetheless, The Americans, which had already established its reputation as a remarkably potent and reliable drama, suddenly became easy to view as a cipher for contemporary issues, whether or not it was intended that way.

The plot revolves around two KGB spies—Keri Russell and Matthew Rhys as Elizabeth and Philip Jennings—enjoying a cozy life in 1980s D.C. with an FBI agent as a neighbor. The show was restrained in its style from the very beginning, eschewing bloody kills as much as possible to make the ones that had to happen really count. It paid special attention to the emotional effect that violence had on its perpetrators, who were often acutely uncertain of whether they were doing the right thing. The storylines in which conflict was ultimately avoided could be more powerful than the violent ones, enhancing an apropos atmosphere of paranoia for an era in which fears of international conflict were just as often baseless as grounded in fact.

Russell and Rhys’s unimpeachable performances drove the show through six slow-burning seasons, the real-life partners subtly exploring the intimacies and contradictions of a marriage arranged by the KGB for the purpose of espionage. Noah Emmerich’s Stan Beeman, the G-Man neighbor, was a perfectly unassuming adversary; for long stretches of the series, it was easy to forget that he was anything other than a close family friend of the central couple. Emmerich rendered his character’s emotional conflicts expertly, even when he was just giving a worried stare and lightly flicking his lip—a weird and unforgettable tic. It’s rare that television portrayals of stoic and repressed people are as emotionally sensitive and credible as these three.

The Americans established its tone, ethos, and mood in its first episode—fear and unfulfillment always hanging thick in the air—and maintained it to the very end. It should be judged on the same level as its star AMC siblings Mad Men and Breaking Bad; at quite a few junctures in its run, it was a cut above. In the Wild West era of the medium, a modest and effective television series that stays the course and knows when to bow out is a rare and valuable thing. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Read our 2018 essay “Goodbye to The Americans, One of the Century’s Finest TV Dramas” here.

Nathan for You (2013-2017)

At the turn of the decade, the United States was still feeling the effects of one of the largest economic downturns in history. The crushing weight of the financial crisis was always bound to fall on the backs of small-business owners, who received little assistance in comparison to leviathanic Wall Street companies’ generous stimulus packages. Hundreds of thousands of Americans had the carpet pulled out from under them, with foreclosure and unemployment rates soaring as part of an implosion many consider more devastating than the Great Depression.

Comedy Central’s Nathan For You focuses on the kind of small businesses that were affected by the recession, and introduces us the people behind them. However, everything is channeled through the singular sensibility of Nathan Fielder, an awkward comedian who plays an exaggerated version of himself as a successful business consultant. After graduating from “one of Canada’s top business schools with really good grades,” Fielder makes it his mission to help small businesses chart a course to profitability. He justifies his value to clients with elaborate schemes ranging from the convincing (installing video ads in bathrooms) to the chaotic (selling poop-flavored froyo, creating something called “Dumb Starbucks”) to the mind-bendingly cruel (forcing gas station customers to climb a mountain in search of an impossible rebate). It’s a journey into the black heart of managerial capitalism, and a candidate for the most original and rewarding comedy series of the decade.

Lots of comedy series have derived punchlines from unsuspecting participants, but Fielder’s genuine sympathy for his victims always shines through in unusual ways. In its incredible Season 4 finale, Fielder helps an old man named Bill Heath track down his high school sweetheart, road-tripping across the country to scour gravestones and attend Heath’s high school reunion. As the episode veers further and further away from its ostensible central storyline, viewers are forced to confront the profound loneliness of the pair’s situation, as Fielder breaks through the artifice he’s sustained throughout series to reveal just a glimpse of something deeper. Even if Fielder left us hanging a little in the end, it’s a poignant and appropriate conclusion to a show about the human cost of corporate ineptitude. —ROB ARCAND

Read our 2017 essay “The Series Finale of Nathan For You Was a Flawless Documentary on the Black Heart of the American Dream” here.

Hannibal (2013-2015)

Let us never forgot how insane it was that NBC greenlit a homoerotic crime show in which the most visually beautiful scenes feature a dandified serial killer either cooking his prey or serving the final product to his unwitting guests. It’s even more ridiculous to think about how such a violent and transgressive show managed to last three seasons on the network, especially with creator and showrunner Bryan Fuller constantly pushing the envelope in terms of what he could get away with. He closed the second season with a scene in which deranged meatpacking magnate Mason Verger (played to perfection by Michael Pitt) slices off pieces of his own face and feeds them to a pack of dogs. Despite this, there was another more Hannibal the following year, even if the show’s time slot kept having to be moved around to accommodate more consumer-friendly shows.

Novelist Thomas Harris’s characters Hannibal Lecter (Mads Mikkelsen), Will Graham (Hugh Dancy), and Jack Crawford (Laurence Fishburne) have been reimagined several times in various films. The most famous Harris-based adaptation, The Silence of the Lambs, earned Anthony Hopkins an Academy Award for the definitive portrayal of the culturally refined “Hannibal the Cannibal.” That makes it all the more impressive that Fuller was able to highlight completely fresh aspects of Harris’ universe in his show. He made a daring but brilliant choice, too, in casting Mikkelsen, a creepy-hot Danish superstar with black shark eyes who was previously unknown on this side of the Atlantic before his turn as a poker-playing, bloody-eyed Bond villain in Casino Royale. Mikkelsen, a former gymnast and ballet dancer, interpreted Lecter with a newfound physicality and muted menace.

Fuller’s flair for baroque visuals also set the show apart not just from other network programming , but from anything on television; quickly, it distinguished itself as one of the best horror shows of all time. The writer and director often borrowed from creators of iconic art-horror films like Stanley Kubrick and Dario Argento, with imagistic, dreamlike episodes that created an experience that felt truly cinematic. Hannibal was never a hit, but the fact that it weathered the storm on the same network that airs America’s Got Talent for 39 episodes is no small triumph. —MAGGIE SEROTA

True Detective (2014-present)

Neither the feverish incoherence of True Detective’s second season nor the muted overcorrections of its third can dull the brilliance of the original, whose mix of lurid murder mystery and beer-drunk existential meditation was not quite like anything else on TV when it aired in 2014. In its wake, there has been no shortage of crime dramas that reach for quasi-mystical profundity. But none have the bottled lightning of creator Nic Pizzolato’s collaboration with director Cary Fukunaga, who helped craft a spectral Southern Gothic atmosphere that more than made up for Pizzolato’s sporadic weaknesses as a writer.

Most of the show’s imitators lack the skill and campy awareness that Matthew McConaughey brought to his role as the reluctant cop and amateur philosopher Rust Cohle. Surrounded by empty Lone Stars in a drab wood-paneled office, Cohle answers questions about a years-old case by offering seemingly unrelated monologues to his unimpressed interlocutors, ignoring queries about dates and evidence files and expounding instead on the cyclical nature of history and the essential loneliness of humanity. McConaughey’s performance acknowledges the terrible truths of these ideas while also conveying the fundamental absurdity of the script’s attempts to explain them. In his deep-fried delivery, a line like “Time is a flat circle” lands both as a grave revelation and as the punchline to a cosmic joke. This duality is crucial to the appeal of True Detective as a whole, right down to the season one finale, in which the show dismantles its own carefully constructed occult mythology and gently chides you for getting so wrapped up in it. Death is always senseless, even when the killer leaves some pretty compelling clues behind.

Season two is better than you remember, though perhaps not in the ways that Pizzolatto intended. It’s like he was shooting for Raymond Chandler and accidentally came up with Thomas Pynchon: the frayed and tangled storylines, which never approach resolution or even recognizable continuity; the bizarre pacing, impossible to keep up with but also unbearably slow; the manically uncanny performances, just a few degrees removed from the real. The disorder of the form expresses Pizzolatto’s ideas about the unmoored experience of contemporary life more truthfully and vividly than the actual content does. In its attempts to keep you interested in an inconsequential tale of municipal corruption and violence, True Detective season two challenges the very notion of narrative, with each of its clumsy turns questioning the baseline assumption that events should flow and develop from one to the next in discernable fashion. Does Colin Farrell discover the Birdman before or after Vince Vaughn has a vision of his dead father in the desert? Where do all those highways lead? Is this a TV show or an amphetamine-induced waking nightmare? Do the words these people are saying mean anything at all? The answers are unimportant. Rust Cohle would approve. —ANDY CUSH

Read our review of True Detective Season 3 here.

Mozart in the Jungle (2014-2018)

Only at a particular Wild West moment in the peak-TV era could a show about a fictional New York City orchestra dealing with the eccentric and self-destructive behavior of a young and capricious foreign conductor (Gael García Bernal) be greenlit by a major corporation, with an expensive star-studded cast, and last for four seasons. Yet Amazon took a chance on Jason Schwarzman and Roman Coppola’s niche half-hour comedy, seemingly giving the showrunners complete creative free reign.

For those who could bear the whimsy and the subject matter, Mozart in the Jungle’s absurd comic romp was singular among contemporary television shows. Its fundamental conceptual inaccessibility was offset by a bizarre and charming ensemble cast (amazing side turns from Bernadette Peters, Malcolm McDowell, Danny Glover, and more) and a welcome lack of self-seriousness. Despite its winks to classical music fans, with passing references and cameos by some of the industry’s most famous figures—from Emmanuel Ax to Joshua Bell and Nico Muhly—it made itself eminently comprehensible, making it possible for viewers with no background in the subject matter to settle into its world.

Mozart in the Jungle featured some continuous throughlines—most importantly, a soap opera romance between Lola Kirke’s protagonist Hailey Rutledge and Bernal’s Rodrigo—but Schwarzman, Coppola, and their co-producer Paul Weitz mostly ignored standard season trajectories and boring tonal continuity, giving equal attention to wacky new B-plots and concepts that made each episode feel like a show unto itself. Mozart’s orchestra began to travel all over the world, fracturing and come back together, grappling with economic and systemic forces which were always threatening to dismantle it for good.

Released in 2014, Mozart was one of Amazon’s initial run of original shows, and the beneficiary of a briefly and strangely utopian period for TV. It is perhaps the clearest example of a corporation throwing everything at the wall in an attempt to cash in on streaming, the fact of its quality a happy near-side-effect of this particular technological and economic boom. The received wisdom of the streaming business has calcified since then, as Netflix programming continues to dominate the conversation and the pressure to produce shows that slot into clear genre categories continues to increase. Sadly, it’s difficult to imagine a big-budget, low-key oddball like Mozart getting funded today. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Read our essay “On Mozart in the Jungle, The Man in the High Castle, and the Twilight of Television’s Golden Age” here.

Happy Valley (2014-2016)

It’s difficult to pull off crime fiction in which the audience gets to know the killer and the detective at the same time, in parallel storylines, without accidentally diffusing the tension of the mystery itself. It’s even dicier when you’re trying to make the killer seem believably human, and even sympathetic. Happy Valley is the better of two major British Netflix-distributed procedurals to take this risky approach across a season-long arc, along with the more popular and star-powered The Fall. A scrappy portrait of cop and criminal rubbing up against each other in a claustrophobic section of West Yorkshire, Happy Valley draws its power the rare intensity of Sarah Lancashire’s performance as police sergeant Catherine Cawood. Lancashire’s character is funny, tough as nails, and reluctant to show vulnerability unless she is pushed to the absolute edge of what a human can tolerate.

Of the many contemporary TV police detectives whose judgment is compromised by past trauma, Cawood’s backstory is one of the most devastating, involving the suicide of a teenage daughter. James Norton plays her adversary, the moody, paranoid, and baby-faced ne’er-do-well Tommy Lee Royce, who often seems too loutish and irritating to be capable of unabashed cruelty. The story of Happy Valley gives Cawood an opportunity to find closure and perhaps revenge for her daughter, and the tension of remaining professional and psychologically glued-together in the face of this possibility, as well as Royce’s unusual dynamism as a villain, animate the show’s action.

Writer and showrunner Sally Wainwright is a modern gem of British television, having made one of the country’s best procedurals after creating one of its most humanistic dark comedies: the septuagenarian love story and family drama Last Tango in Halifax. And Lanchasire is a triumph, giving one of the strongest leading performances by any actor in a drama series in recent memory. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

The Leftovers (2014-2017)

At first, it seemed like a recipe for disaster—or at least, eventual disappointment—that Damon Lindelhof had produced another cryptic dramatic television show. But with his speculative HBO epic The Leftovers, the polarizing writer and director responsible for Lost not only managed to deliver a satisfying and modest three seasons of television; ultimately, the show turned into perhaps the most structurally adventurous drama ever produced by the network. As an adaptation of Tom Perrota’s episodic 2011 novel, Lindelhof’s series initially played out like an extended Twilight Zone concept with hard-to-parse Christian overtones, but went far beyond its initial premise in its second and third seasons. Lynchian free-associative imagery and plotlines were certainly part of the bargain, but Lindelhof successfully tread the fine line between intriguing subjectivity and self-indulgence. The bottle episode became one of the show’s primary modes of operation, leading to installments that felt like chapters in a postmodern novel rather than serial television episodes. (This was especially in the third season, with its vestiges of the Kevin Finnerty Sopranos episodes). By committing to an uncompromisingly non-linear method of storytelling, Lindelhof trained viewers to stop expecting plot lines and mysteries to be worked through conventionally, or worked through at all—challenging the idea that cliffhangers should always be followed up on, or characters’ motivations elucidated. The power of the characters, speculative concepts, and mise-en-scènes made his most alienating choices feel justified.

After all, the feeling of strands left untied is the subject of The Leftovers, as well as the impression it often leaves you with as the credits roll on an episode. It takes place in a version of our world where most of the population is searching for order and purpose amidst chaos and omnipresent collective grief. Some of its characters keep attempt to live their lives as if the Sudden Departure never happened, continuing to trust in the conventions of family, morality, and societal infrastructure that used to tie their lives together. Ultimately, they can’t rein their impulses in; in their own ways, they are forced to accept that they have become something different than they were. Watching them—most rewardingly, the excellent Justin Theroux and Carrie Coon’s character—gradually work around to that conclusion, and find their own curious form of peace with it, is the show’s most crucial trajectory. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Read our 2017 essay, “In Season 3 of The Leftovers, Everyone Is Waiting Around to Die,” here.

Fresh Off the Boat (2015-present)

Since Margaret Cho’s All-American Girl left the small screen in 1995 after just one season on ABC, Asian-American culture has barely been represented on network television in a three-dimensional way. Sure, there have been notable characters (shoutout to Sandra Oh on Grey’s Anatomy, Lucy Liu on Elementary, BD Wong on SVU and AHS, Mindy Kaling on The Office and Mindy Project, among others), but the experience of being Asian in America is rarely a focal point. That is why Fresh Off the Boat, a comedy series created by a female Asian showrunner and starring an entirely Asian cast, felt like such an anomaly at the time of its premiere in 2015, and why it remains so important.

Premiering on the same network 20 years after Cho’s groundbreaking series, Nahnatchka Khan’s show gave a primetime TV audience a rare glimpse into the daily lives of a specific group of Asian-Americans. Set in the ‘90s and inspired by chef Eddie Huang’s memoir of the same name, the family at the center of the show (portrayed by Constance Wu, Randall Park, Hudson Yang, Forrest Wheeler, and Ian Chen) is Taiwanese-American and living in suburban Florida. The show explores many Taiwanese and Chinese traditions, and shows U.S.-raised children trying to assimilate even as their parents insist on keeping traditional Asian culture and values alive at home—and sometimes at school. How many American scripted shows—sitcoms or dramas—have devoted entire episodes to “sitting the month,” Chinese New Year, and the difficulties of applying for citizenship? How many feature major characters who only speak in a non-Western foreign languages, or showcase foods that might make the non-Asian viewers scratch their heads in confusion?

Fresh Off the Boat showcases and embraces these cultural practices, juxtaposing them with more distinctly Western traditions and rites of passage like Halloween, the first school dance, and getting a driver’s license. Obviously, this causes some tension: the teenager who loves rap and Shaq is the black sheep of the family. Now entering its sixth and likely final season, Fresh Off the Boat deserves credit for characterizing the daily experience of a sizable group of Americans that are incredibly underrepresented in popular culture, and doing so with plenty of sensitivity, heart, and humor. —ANNA CHAN

Making a Murderer (2015-present)

The clearest prototype for the high-end true crime programming that has overtaken TV and streaming in this decade is Errol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line, a hypnotic 1988 documentary that investigates a murder from different perspectives in an attempt to exonerate a man who had been falsely convicted. By early 2016, the first three defining documents of the modern true crime renaissance—2014’s investigative podcast Serial, 2015’s HBO miniseries The Jinx, and Netflix’s 10-episode epic Making a Murderer of the same year—had become major cultural phenomena, attracting a level of internet-forum watercooler discussion to rival the most popular scripted series of the time. Eventually, someone asked Morris for his take on the bumrush. The legendary documentarian told Slate he was enamoured with and even “jealous” of Making a Murderer, which he categorized as an “extended essay using found footage.” He explained: “I found it extraordinarily powerful, and ironic, because there really is no investigation...It’s reporting other people’s investigations.”

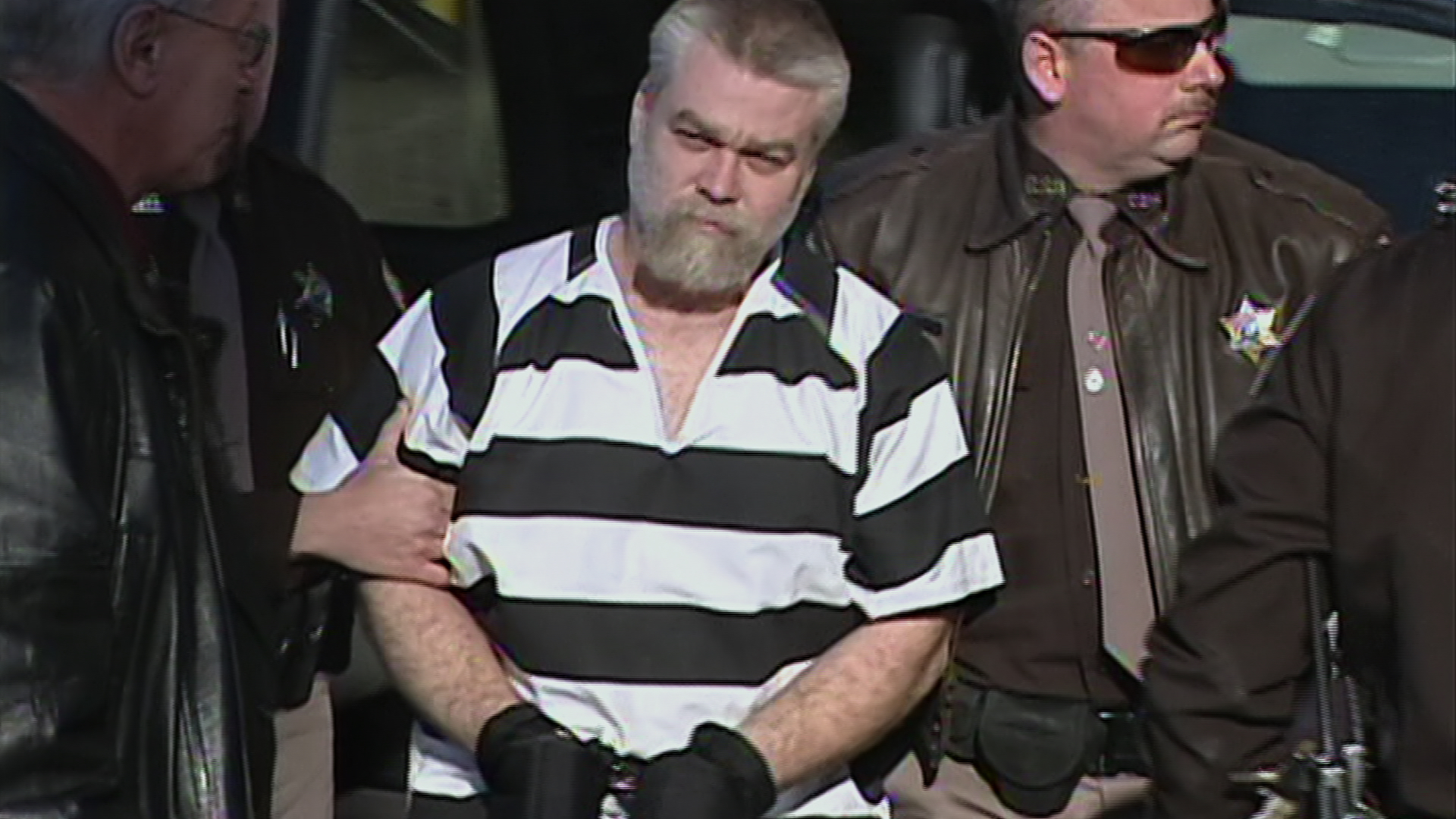

Whereas The Thin Blue Line, Serial, and The Jinx sought answers to their rediscovered cases—to dig up new evidence and present it dramatically, to re-enact events in myriad ways in hopes of locating a hidden truth—Making a Murderer mostly just presented existing information. Filmmakers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos reported the series over 10 years, chronicling the trials of convicted murderers Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey, but also telling a story about their families, Avery’s coming-of-age and struggles as a younger man (very much related to the final case), Wisconsin’s Manitowoc County as a whole, and several dark and grimy corners of the American legal system.

Ultimately, Making a Murderer does not work towards exonerating Steven Avery or Brendan Dassey, or push us decide whether they are guilty or not. Instead, it shows us how local law enforcement did many things outside its purview in the process of getting them to jail and keeping them there. (The second season, which is overall a significantly weaker project, does shed light on Dassey’s almost comically difficult struggle to be released while his case is being reevaluated.) The show offers a variety of convincing possibilities for how and why a small town police force might rush to close an investigation preemptively and perhaps improperly. It leads the viewer toward seemingly inevitable conclusions, but it uses its runtime rigorously, documenting each step of the legal process and fairly characterizing its subjects.

Ultimately, as Morris puts it: “One thing that you do learn in an investigation is that we’re all prisoners of narrative, and we can’t escape from narrative.” Making a Murderer gives us more compelling potential storylines than perhaps any other true crime series of the modern era. For better and for worse, it’s also one of this decade’s most influential documentaries. Since the release of its first season, it has helped inspire a range of shows and films, from poor imitations to projects that have actually worked to help wrongfully convicted incarcerated people. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Billions (2016-present)

Billions exists in a sweet spot in the aspirational wealthy-bro-drama genre to which it belongs. It’s easy to imagine a new TV show in this style instantly turning off the uninitiated 2019 viewer and coming across as hackneyed. But unlike predecessors like Oliver Stone’s heavy-handed and often misinterpreted Wall Street, the Showtime series offers no cautionary tales or earnest condemnations of capitalism. Unlike the exhilaratingly decadent The Wolf of Wall Street, the characters, for the most part, are not irredeemable sociopaths, and the reckless partying is largely reserved for one character: the indefatigable Mike “Wags” Wagner (David Costabile). Most importantly, unlike the dumber-than-a-box-of-rocks Entourage, Billions is a meticulously crafted show, with writers who create elaborate—if ridiculous—plots that remain inevitably satisfying, even four seasons into its run.

Showrunners Brian Koppelman and David Levien also know which parts of the films and shows that inspired them do work, and borrow from them when appropriate. Bobby “Axe” Axelrod (Damian Lewis), the hedge fund manager with the aforementioned billions who serves, alternately, as a villain and hero in the series, flies in private jets and drives absurd sports cars and pals around with celebrities like Metallica and Kevin Durant, just like an Entourage character. In season two, Axe spots a rare spark in a talented intern named Taylor Mason (Asia Kate Dillon) and takes them under his wing, revealing the intoxicating effects of great wealth and power—just as Wall Street’s Gordon Gekko does to Bud Fox. And of course there’s Wags’ hedonism, which, if not quite on the level of Wolf’s Jordan Belfort snorting cocaine from a prostitute’s ass, is close and at least as fun.

Outside of Axe, the show’s other protagonist is Charles “Chuck” Rhoades, Jr. (Paul Giamatti), the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, who is obsessed with catching Axe in one of the many financial crimes Chuck is (correctly) convinced that the hedge funder has committed. There’s another reason for Chuck’s obsession: His wife Wendy (Maggie Siff) works at Axe Capital as a highly paid in-house therapist and professional confidant who is privy to many of the company’s secrets. This gargantuan and clearly untenable conflict of interest gets at another of Billions’ charms. Like any great show, it operates in a universe that is entirely its own, following rules that make sense only if you surrender to that fact that it’s not taking place in reality, despite the surface-level similarities. It’s a testament to the success of Koppelman and Levien’s world-building that their dialogue—often so densely packed with obscure pop culture references that it sounds like something Bill Simmons might have written on crank—is one of the show’s many strengths and not grounds for ridicule. Their gonzo Billions-world logic allows us to accept story arcs that are as ludicrous as they are expert, involving things like elaborate stings built around the coordinated poisoning of a fresh juice chain’s products on the day of its IPO. Combine the fearless writing style with the A-list stars obviously having a blast, and a murderer’s row of great character actors in supporting roles, and you get the most entertaining show on television. —TAYLOR BERMAN

Read our 2018 essay “Billions Is Back and Still More Fun Than Your Favorite Peak TV Drama” here.

American Crime Story (2016-present)

In 2016, both the sprawling ESPN documentary O.J. Simpson: Made In America and FX’s scripted series American Crime Story: The People vs. O.J. Simpson explored the way in which Simpson’s murder trial became a powder keg that exacerbated racial tensions inpost-Rodney-King America. But American Crime Story leaned into the trashiest aspects of the story, exploiting our morbid fascination with celebrity scandals to unusual and polarizing effect. Developed by writers Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski (Ed Wood, The People vs. Larry Flynt), The People vs. O.J. Simpson offered a melodramatic and arch portrayal of the so-called “trial of the century, while also powerfully evoking the racism, toxic masculinity, and violence that factored into the trial, the media circus surrounding it, and the crime itself.

Above all else, it was the show’s cast allowed the risky project to succeed. Its best performances felt emotionally nuanced as well as hyperbolic, including Courtney B. Vance’s Johnnie Cochran, Sterling K. Brown’s Chris Darden, and Sarah Paulson’s Marcia Clark. John Travolta’s Robert Shapiro, David Schwimmer’s Robert Kardashian, and Cuba Gooding Jr.’ O.J. were more bizarre, but their scenery-chewing characterizations provided an interesting point of contrast and served their specific purpose in the story well.

American Crime Story’s first season was a huge success for FX, which is not surprising given the high-profile subject matter. To follow it up, the show tackled a darker and less ubiquitous tale: Gianni Versace’s murder at the hands of serial killer Andrew Cunanan. Versace lacked O.J.’s intermittent lightness and absurdity, painting a heartbreaking and deeply disturbing portrait of a kid losing his grip on sanity in his pursuit of glory. (Darren Criss’ pitch-perfect performance as Cunanan was ultimately the season’s highlight.)

In the 2010s, Ryan Murphy established himself as one of television’s most distinct voices, and quite possibly its most influential. The Glee and American Horror Story creator has an inconsistent track record—he produces so many shows that it would be almost impossible for it not to be—but his loud and theatrical style is particularly well-suited to tales of real-life violence and depravity, heightening their most lurid elements without losing sight of their essential humanity. In taking a bold and singular approach to sensitive subject matter, American Crime Story encapsulated the best parts of the Murphy empire’s creative legacy. —ISRAEL DARAMOLA

Read our 2016 essay “Let’s Appreciate The People v. O. J. Simpson’s Emmy-Worthy ‘N***a, Please’ Scene” here, and our 2018 essay “Gianni Versace Is the Beating Heart of the Show About His Death” here.

Flowers (2016-2018)

Ten years ago, getting access to a relatively obscure British show like Flowers might require you to purchase a set of DVDs online, or to risk your internet access by downloading an illegal torrent. Now, it’s as easy as cueing up the correct Roku channel. For all the faults of the streaming era, it’s undeniable that Netflix, Hulu, and their ilk have made it easier for Americans to access the sorts of idiosyncratic international shows that might not have crossed the pond otherwise. One of the strangest and most inspired shows in this category to show up on a major streaming service was Flowers, a two-season black comedy starring Julian Barratt and Olivia Colman as a suicidal children’s book author and his long-suffering wife.

In this decade, especially its second half, discussions of mental health have been a welcome component of the pop-cultural zeitgeist. On TV, this tendency has mostly manifested in the post-Girls idiom of stylishly quotidian shows about depressed millennials working in coffee shops and having bad sex. Flowers bucks that trend in spectacular fashion, putting the depression of Barratt’s patriarch Maurice Flowers and the inherited trauma of his wife and two children at the center of a fanciful and surrealistic tale that also involves a lapsed clown, a troupe of avant-garde musicians, a hysterical nymphomaniac neighbor, and a lesbian ex-junkie priest. The show’s wild visual and narrative languages often feel like manifestations of its characters’ inner states: sometimes foggy and slow, other times feverishly paced and deliriously colorful.

Series creator Will Sharpe plays a bumbling but kindhearted Japanese-British illustrator, a role that dares you to laugh at what would at first seem like an ugly caricature of Sharpe’s own heritage, but soon becomes much more complicated. Flowers as a whole is similarly steadfast in its refusal to offer the viewer predictable comforts, giving a depiction of mental illness that is boldly inventive, crushingly sad, ridiculously funny, and uncommonly true. —ANDY CUSH

The Night Of (2016)

HBO’s limited series The Night Of’ offered a nuanced take on the criminal justice system, exploring the fallibility of every party involved without indulging in overblown cartoonish portrayals of corrupt cops and bloodthirsty criminals. This attention to detail earns it a place among the top tier of this era’s crime shows, like a small-scale procedural version of The Wire, which series co-creator Richard Price helped to write.

In its pilot, a young Pakistani-American kid named Naz (a thoroughly impressive Riz Ahmed) is apprehended near the scene of a grisly murder, with incriminating evidence on his person. Over eight episodes, the question of Naz’s guilt is explored in police precincts, in courtrooms, and in the claustrophobic cells of Rikers Island, where Naz is left to await trial. Facing the cynical institution that is the New York County District Attorney’s Office with nothing more than a budget defense attorney (John Turturro), the once-naive Naz wises up pretty quick, mingling with high-profile prisoners and picking up a crack addiction in the process. The city’s attorneys know something’s not quite right with the case, but they need a win badly enough that they don’t really care. And Naz’s shabby attorney, though his heart seems to be in the right place, doesn’t have the legal chops to make a compelling case on his behalf.

Everyone is falling apart, physically as well as psychologically and ethically (Turturro’s character has a severe eczema problem that fluctuates along with Naz’s case). Nothing works quite as it should, and there isn’t a single character on this show that escapes the inevitability of compromise. The Night Of’s most memorable moment may be its last—when a free Naz, his head now shaved, his body tattooed, looks out onto the Hudson and takes a hit from his crack pipe, thinking back on the naive college student he once was. Across the city, his committed attorney takes a call from a new client. The state of criminal justice hasn’t changed, though Naz has. And it’s the same for the countless others, whose experience of a deeply imperfect system comes to shape their lives irrevocably. The river rolls on. —WILL GOTTSEGEN

Read our 2016 interview with Riz Ahmed about The Night Of here.

Vice Principals (2016-2017)

Comedy auteurs Danny McBride and Jody Hill are experts in evoking a particular strain of Southern life. In both their inspired debut HBO series Eastbound and Down and its superior followup Vice Principals, the showrunners’ protagonists—both played by McBride—are amplified versions of a familiar type of Carolina-born idiot. Eastbound’s self-destructive ex-pro-baseball pitcher Kenny Powers is the definition of a has-been, and high school vice principal Gamby is perhaps better characterized as a never-has-been. They are at turns cocky, selfish, vain, insecure, and cruel, but—if you squint hard enough—also empathetic and somehow worthy of redemption. They are also inevitably hilarious, with McBride’s buffoonish presence and precise delivery highlighting the gap between his characters’ self-perception and their actual standing in the world.

In Walton Goggins, Vice Principals has a perfectly cast second lead. As Lee Russell, Gamby’s dandyish co-vice principal at North Jackson High School, Goggins prances and peacocks around in outlandish suits that should’ve won the show’s costume director every award on earth. Whereas Gamby is an oafish disciplinarian, who huffs and curses his way through life in short sleeve button downs and clip-on ties, Russell is an ingratiating sycophant desperate to weasel his way into a position of true power at the high school. The retirement of North Jackson’s longtime principal and announcement of an outsider, Dr. Belinda Brown (the excellent Kimberly Hebert Gregory), as his successor triggers a seemingly infinite number of insecurities within Gamby and Russell. The two former rivals join forces to sabotage Brown’s tenure, ramping up their antics from petty in-school hijinks to full-fledged arson.

Over its two seasons, the show spends an increasing amount of time detailing Gamby and Russell’s warped personal lives. We see Gamby struggle to connect with his daughter Janelle (Maya G. Love), his ex-wife Gale (Busy Phillips) and her new husband Ray (Shea Whignam), all of whom are trying their best to support him despite his constant unprovoked antagonism. He has a disastrous fling with one co-worker and a more substantial but doomed relationship with another. It’s hard to know if the dysfunction and failures of his professional or personal life are worse, but the end result is the same: he’s profoundly fucked up. The second season focuses in on Russell’s life at home, in particular his relationship with his long-suffering wife Christine (Susan Park). As a doctor, she is more professionally successful than he is, which clearly eats away at him. No matter how hard she tries, she can’t do enough to assuage his myriad vanities and ambitions, and as a result, Russell repeatedly insults and humiliates her (along with her Korean mother, who lives with them and hates Russell). At various points, Hill and McBridge suggest deeper motivations for Russell and Gamby’s insecurities and moments of cruelty: Russell is a youngest sibling with two sadistic sisters who tormented him as a child, and watching Gamby attempt substitute teaching for a day reveals he’s less educated than the average upperclassman in an AP class. However, at no point does the show’s writing excuse or justify their behavior, or make their undeserving targets the butt of the joke.

As bleak as the concept of two mediocre middle-aged men sorting out their insecurities in increasingly destructive and depressing ways sounds, the show is still somehow one of the funniest comedies of the past ten years. McBride’s vision and sensibility remains unique, at once juvenile—he revels in dick-and-balls slapstick humor and innovative cursing—and profound. The deeper struggles of his characters are always clear but they exist on the periphery, fueling the comedy rather than providing a counterpoint to it. We laugh at Gamby and Russell as they bumble through a world they’re too stupid and damaged to thrive in, insulting and belittling everyone in their path, because we know at the end of the day the joke is on them. —TAYLOR BERMAN

Fleabag (2016-2019)

Phoebe Waller-Bridge has a staunch quit-while-you’re-ahead attitude. When you’ve created, written, and starred in two perfect seasons of television, wanting to go out on top is understandable enough, even if viewers may feel deprived of potential future greatness.

The most brilliant aspect of the 12-episode run of Fleabag, Waller-Bridge’s dark comedy for Amazon, is how deeply it immerses us in the intensely complicated inner life of the main eponymous character—the series’ dirtbag anti-hero. We experience her grief, depression, and familial trauma, as well as a fear of intimacy so pervasive that she never even tells us her name. Fleabag communicates with the audience by breaking the fourth wall, privileging us with information that we then watch her keep from the people closest to her. As Vulture’s Jen Chaney pointed out during the show’s first season, every time Fleabag addresses the camera, she’s telling you something she’s afraid to tell the people closest to her, but desperately needs someone to hear and understand.

It’s in these pointed asides that show’s biggest laughs usually come—whether Waller-Bridge’s character is unloading impure thoughts about an obscenely hot priest (Andrew Scott) or providing the venomous subtext to a stealthy slight from her passive-aggressive mother-in-law (Olivia Colman). In those moments, Fleabag communicates more with a flicker of a glance or the slight curl of the lip than an entire season’s worth of Jim Halpert bemused reaction shots. —MAGGIE SEROTA

Read our 2019 essay “Fleabag Season 2 Gives a Fresh and Honest Perspective on Grief” here.

Atlanta (2016-present)

At first, Atlanta—the brainchild of actor, rapper and comedian Donald Glover—seemed like an unlikely prospect. A show about a rapper living in the most bustling city in hip-hop, made by a guy who once rapped about Asian fetishes and being the only black guy at Sufjan Stevens concerts, seemed like a recipe for comic misfires and generally embarrassment.

Instead, the FX series ended up playing to Glover’s strengths as an actor and comedian, doing oddball service to the city. With the help of a crack team, including directors Hiro Murai and Amy Seimetz and writers Stephen Glover and Stefani Robinson, the show offers a complex and nuanced look at the everyday business of being a mid-tier street rapper in a city that is full of them. It offers oblique commentary on fame, pop culture, and family, as well as uncommonly truthful and empathetic portrayals of black southerners and young people whose lives have run astray.

Atlanta follows Earnest (Glover), a college dropout who hopes to glom onto the local success of his rapper cousin Alfred, aka Paper Boi (Brian Tyree Henry), and also prove that he can be a provider for his young daughter and sometime partner Van (Zazie Beetz). But the show is at its best when it departs on surreal tangents from its guiding plotline. Episodes like “Juneteenth” and the season two premiere “Alligator Man” are isolated forays into the lives of characters at the edges of the show: the former finds Earn and Van attending an extravagantly weird dinner party of a wealthy mixed-race couple, and the latter centers around Earn’s uncle Willy (Katt Williams), who exemplifies a worst case scenario for Earn’s professional career. Season two standout “Woods” takes a bizarre approach to exploring the trauma people carry around with them unknowingly, taking Alfred on a dreamlike spirit quest.

Perhaps Atlanta’s most infamous episode is “B.A.N.,” which is basically Glover and company’s extended version of a Chappelle’s Show skit. Alfred goes on a public access talk show to defend his offensive lyrics from the criticisms of an educated feminist, complete with a series of hilarious fake commercials for Arizona Iced Tea and a Trix-like cereal, reaching an unexpectedly disturbing climax that we won’t spoil here. With “B.A.N.,” Atlanta definitively proved that it could be whatever it felt like being from week to week, and audiences agreed to go along for the ride. —ISRAEL DARAMOLA

Read our 2016 essay “Donald Glover’s Atlanta Is Black and Essential” here.

Twin Peaks: The Return (2017)

When Twin Peaks premiered on ABC in 1990, it seemed like it could be a typical crime procedural. The plot seemed to revolve around a dead homecoming queen, a do-right lawman, and a small town full of secrets—nothing too out of the ordinary. However, it became clear soon enough that David Lynch and Mark Frost’s whodunit was something much more unusual and unprecedented. It explored otherworldly mysticism and adopted a postmodern approach that sometimes served as a hilarious commentary on popular television genres of its era, including daytime soaps, teen dramas, and mystery-of-the-week stories.

The adventures of Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) and the residents of the town of Twin Peaks only aired for a little over a year, but the show remained consistently exciting, confounding, and truly strange throughout its 30-episode run. Still, the idea that 27 years later, a network would mount on a reboot of the series—and one that was significantly more experimental—must have seemed incredibly unlikely after the show’s cancellation for sagging ratings, and especially in the wake of the commercial failure of its follow-up film Fire Walk With Me in 1992.

Of course, Twin Peaks and Fire Walk With Me were released before David Lynch had solidified his reputation as one of the most uncompromising and influential filmmakers of all time. As his profile rose, the cult around the Twin Peaks universe expanded greatly. By the mid-2010s, the director’s style was much better understood and accepted by fans and industry executives alike, and television had turned into a diverse medium that could accommodate Lynch’s expansive vision for a new Twin Peaks story.

With Twin Peaks: The Return, Lynch and Frost returned to the eponymous town to explore the secrets and traumas still haunting it 25 years later. Cooper’s doppelgänger from the Black Lodge, or Mr. C (MacLachlan), has been terrorizing the world the real Cooper has remained stuck in the Lodge. Cooper is meant to re-enter the world after 25 years and automatically replace Mr. C, but the evil twin has devised a plan to keep himself around and trap Cooper in the body of Dougie Jones, a shady businessman in Las Vegas. While stuck in that body, Cooper is initially barely able to move or speak, let alone track down his double. In the meantime, Twin Peaks’ deputy police chief Hawk (Michael Horse), deputy Andy (Harry Goaz), and Sheriff Truman—not the original but his brother, played by Robert Forster—revisit the Laura Palmer case, while FBI agents Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrar), Gordon Cole (Lynch), and Cooper’s former assistant Diane Evans (Laura Dern) investigate a series of connected “Blue Rose” cases. This is only the tip of the iceberg: the series introduced many other new characters, locations, and mysteries, making the town of Twin Peaks itself hardly even the focal point.

Less light-hearted than the ABC seasons—to say the least—certain sections of The Return function like extended meditations on suffering, the tangled legacies people leave behind them when they die, and the ways in which we carry grief with us throughout our lives. There are strangely tear-jerking moments, and drawn-out sequences that seem intentionally tedious. For some reason, most episodes end with a musical performance, like Lynch’s take on Saturday Night Live. Inevitably, the often-inscrutable series makes a point of shifting gears just when you think you understand what’s happening.

And just as the original series did, The Return interacts with the conventions of television in the modern age, stacking its cast with “difficult men” and scenes of unsparing violence. It also set an important example for other creators of reboot series and films, which are only becoming more popular in the era of streaming TV and Marvel movies. The Return foiled pre-existing expectations to dazzling effect, exemplifying how filmmakers can resume an old creative project in a dynamic way, and without leaning on nostalgia and fan service.

More broadly, Twin Peaks: The Return proved that in our current era of small-screen oversaturation, the medium can still provide new opportunities for directors and writers. Few showrunners could reasonably pull off an experiment this strange and grand-scale—and not even Lynch and Frost managed to land a ratings hit—but that doesn’t mean people shouldn’t keep trying. —ISRAEL DARAMOLA

Read our 2017 essays “Twin Peaks Ended, Once Again, With a New Beginning” and “Why Twin Peaks: The Return Was One of the Funniest Shows of 2017” here and here.

American Vandal (2017-2018)

As this decade’s fetish for high-end true crime programming turned into an industry craze, driven by breakout hits like Serial and Making a Murderer, the genre received its fair share of parodies, but none disrespected the form more satisfyingly than Tony Yacenda and Dan Perrault’s Netflix scripted comedy series American Vandal. The show applies a trendy template—an earnest journalist investigating a controversy on behalf of the accused—to the dumbest possible crimes. In the first season, someone spray-paints penises on high school teachers’ cars, and in the second, someone sneaks laxatives into a high school cafeteria’s lemonade supply. Vandal’s central joke—painstaking, poker-faced analysis of doofus pranks—manages to get funnier as the pranks are broken down from every possible angle by straightfaced student journo Peter Maldonado, played by Tyler Alvarez, over the course of many hours. He is assisted by his friend and partner Sam Ecklund (Griffin Gluck) and their several dozen sources, including a nun who explains: “This poop was not wet and gooey, this was more of a poop dusting.”