Arguably overstuffed with familiar sci-fi tropes pertaining to cloning, mind control, and the oft-malevolent motivations behind historical social reforms, director Juel Taylor’s They Cloned Tyrone — co-written by Tony Rettenmaier (Space Jam: A New Legacy, 2021) — prefers to hover in the realm of lightly socially conscious comedy, sometimes to the material’s detriment. Adjacent to something like Boots Riley’s infinitely more troubling and unapologetically bonkers Sorry to Bother You (2018), Taylor’s directorial feature film debut often feels more exciting to talk about as a conversation piece than as a viewing experience, with its leading trio of characters more often competing than coalescing.

Also Read

Takin’ It Too Deep

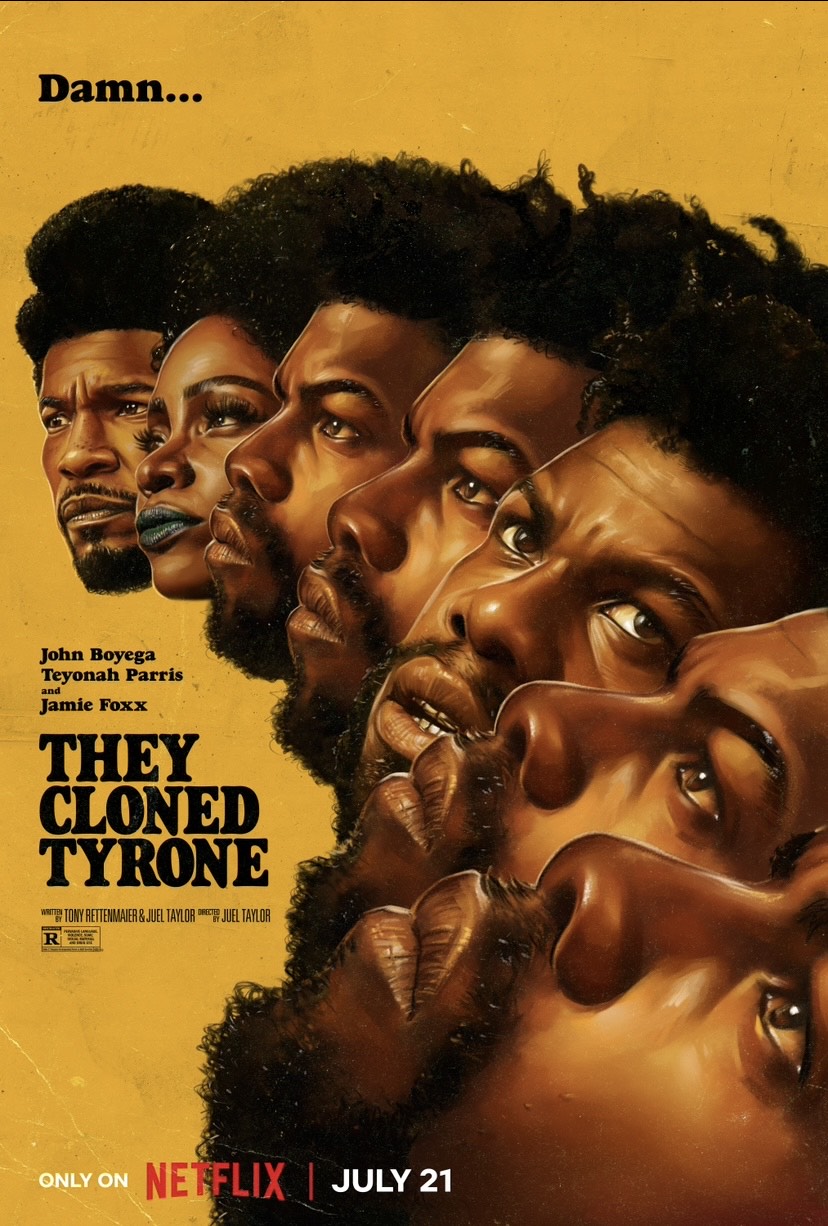

Struggling to retain his territory in The Glen, a neighborhood in a Black, urban metropolis where the license plates facetiously read “A Swell Place,” drug dealer Fontaine (John Boyega) is gunned down by rivals in a motel parking lot. Awakening the next morning perfectly healthy, but retaining his memory of the shooting, Fontaine tracks down the pimp Slick Charles (Jamie Foxx) and sex worker Yo-Yo (Teyonah Parris), who witnessed the crime. Together, the three of them locate the vehicle Fontaine’s murderers were driving and eventually find an elevator leading to a subterranean lair. It seems some secret governmental organization is performing devious experiments on the community. The more they dig, the closer they cleave to danger, leading to revelations none of them could predict.

Ultimately, They Cloned Tyrone often feels like something of a missed opportunity, eschewing how technological realities would likely have furthered the plot’s catalysts more effectively. Prizing a gritty, 1970s palette courtesy of DP Ken Seng (Deadpool, 2016), Taylor’s influential cinematic reference points are in full force. Its principals are a hodgepodge of homage to Blaxploitation cinema, with Parris directly compared to Pam Grier’s iconic Foxy Brown (1974), while Boyega channels the endearing innocence of early Glynn Turman, specifically in the haywire hybrid J.D.’s Revenge (1976).

But it’s Jamie Foxx as a pseudo flamboyant pimp, in the tradition of Rudy Ray Moore, who scores most of the laughs (particularly opposite Parris, whose vivaciousness matches his). In the film’s extensive lead-up to major revelations, Boyega’s studious, mannered persona often feels sublimated by their energy. The three of them play like a reconfiguration on themes explored in Gordon Parks Jr.’s 1974 flick Three the Hard Way, where Jim Brown, Jim Kelly and Fred Williamson thwart a nefarious plot by white supremacists attempting to poison the nation’s water supply with a toxin only fatal to Black people. However, Taylor’s timeline often seems confused in its attempt to sidestep the onset of social media, where flip phones, analogue technology, and a reference to Denzel Washington in 2010’s The Book of Eli suggest the time period to be the early 2010s.

They Cloned Tyrone really kicks into gear when the investigating trio (who appear to be taking a page from Nancy Drew’s techniques) infiltrate the Mt. Zion church with David Alan Grier, in his sole sequence, preaching to a congregation clearly modified by mind-altering substances administered in their grape drink. Suddenly, the film feels like Jordan Peele’s version of Aaron McGruder and Mike Clattenburg’s Black Jesus. Medical experiments resembling Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) (the filmmaker is referenced again with a DJ credited as Strangelove) or Michael Crichton’s Coma (1978) enhance the narrative’s vintage flavors, especially paired with its themes on cultural annihilation as a form of assimilation. Cultural traditions and beliefs, including social and religious, inherently become the mechanisms allowing for the ultimate form of captivity, imploding the film’s subtexts into shards of Marxist admonitions underlined by Langston Hughes.

What happens to dreams unceasingly deferred by social-induced stupors? Well, it would seem inevitable obliteration via cultural extinction. There’s a thread of something quite revolutionary at play in They Cloned Tyrone, not unlike the outline of schizoanalysis in Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus, where schizophrenia is posited as the only balm to capitalism, the ultimate disruption of a harmful system because it refuses the codifications to participate in its rigid dictates.

The whitewashing of culture into a controllable assimilation nation is really the troubling theme of They Cloned Tyrone, even if Taylor’s film sidesteps actual confrontation by trying to provide some semblance of resiliency. There’s enough food for thought to make an impression, but ultimately They Cloned Tyrone should feel more provocative either as a mordant comedy (something this year’s The Blackening leans into) or a troubling exploration on how capitalism’s survival depends on our compliance and obliviousness to conformity.

Watch Nick and his husband Joseph review (and spoil) films on their YouTube channel, Fish Jelly Film Reviews. Their podcast of the same name is available everywhere.