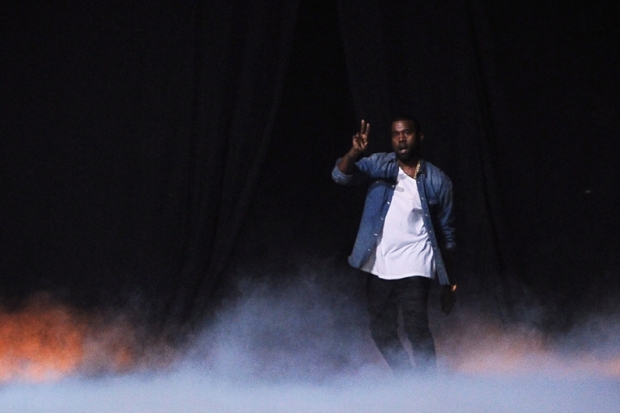

Kanye West’s latest, Yeezus, was supposed to be his statement-making, punk-infused noise-rap record: A rousing, leather jacket-sporting, Saturday Night Live appearance premiered the incendiary “Black Skinhead” and a fascinating New York Times interview (in which Kanye reminded readers of his connection to dead prez), seemingly prepped listeners for a burst of realer-than-real talk from a wildly popular rapper without a whole lot to lose at this point.

Instead, Yeezus is a relentless spleen-vent against the women in his life — the women he’s fucked or wanted to fuck or who fucked him over or lied to him or whatever, that’s occasionally provocative thanks to political asides that West has done more with more nuance and humor in the past. Frankly, even calling Yeezus (particularly it’s lumpier second half) a “spleen vent” mischaracterizes its wounded bro rage. This intends to be a raw, ugly album, and it is. When Rick Rubin tells the Wall Street Journal that much of the record was completed in just two days, it makes a lot of sense. Yeezus sounds like an album knocked out in less than two days.

On paper, there is something refreshing about Kanye rejecting the minor-key misogyny of 808s & Heartbreak – which Drake has managed to turn into a career — and just “goin’ in,” as it were. But Yeezus couldn’t have come at a more problematic moment for rap — smack in the middle of a year where it seems like misogyny in the genre might be hitting a tipping point. We all have our “I give up” moments and Yeezus found me reevaluating rap’s nastier aspects. I still believe that part of rap’s power comes from its ability to put everybody up against the wall. Anything that makes people of varying political persuasions and sensitivities uncomfortable is a great thing.

At the same time, however, rap feels like it is reverting. Most notably, it has been shoved back into the strip club, and with that has come a woozy, dark, too-many-drugs vibe that producers have cribbed from eccentric Internet rap and R&B groups like the Weeknd. The result of this aesthetic shift is that the shake club, at least in much rap and rap-influenced music, has transformed from an exploitative, but often joyfully escapist setting for songs, to a disturbing and evil locale of lecherous lurkers and predatory creeps. Consent gets foggy because a lot of drugs are being thrown around in these songs. Tellingly, Yeezus‘ sole guest verse is from King L, a Chicago rapper whose semi-hit from last year was titled “My Hoes They Do Drugs.”

Issues of consent in hip-hop party rap became too big to ignore earlier this year when Rick Ross rapped about “put[ting] molly” in a woman’s drink and then having sex with her on Atlanta rapper Rocko’s stoned street hit, “U.O.E.N.O.” Here was someone quite literally making explicit what so much of the genre had been saying more carefully or in coded slang: Drugs and alcohol serve as a way to take advantage of women, all under the guise of having a good time. At the time of the song’s release, I acknowledged those lines by pointing out that they were “horrifying [and] rape-y,” but then I just kept it moving. That’s more than some other critics and blogs did, but it makes me feel uncomfortable in retrospect. Namely, it was a half-step to free me to wax poetic about Childish Major’s beat without feeling so guilty.

Thanks to protests and outraged thinkpieces, which put the spotlight on “U.O.E.N.O,” Rick Ross lost his Reebok sponsorship. And the aftermath of “U.O.E.N.O.” was surprisingly well-handled: Ross was removed from the song and dozens of remixes appeared burying his voice; a nice grace note was Black Hippy’s ScHoolboy Q adjusting Ross’ lines: “This hoodie here about two stacks / Hell yeah, that bitch could go ham / Molly in her drink, but she asked me to, and oh yeah, I got this on cam.” Hip-hop governed itself, it seemed, and the various protests were effective. But for the most part, when it came to this issues, rap writers weare pathetically silent.

Other moments have also suggested a collective “enough’s enough”: Lil Wayne lost his endorsement deal with Mountain Dew after rapping “beat the pussy up like Emmett Till” on Future’s “Karate Chop”; Protestors at a show in Australia confronted Tyler, the Creator (who also had his female problems when he directed a Mountain Dew ad) and Tyler responded by calling the protestors “cunts” from the stage; Action Bronson, who seems to pushing the limits of working-class-dude misogyny the higher his profile rises, has suffered a minor backlash over the cover of his new EP, Saab Songs (it features two women doing something or other in the bathroom as Bronson looms over them); the possessive nice-guy cruelty of Drake, J. Cole, and others has become a bit of a “SMDH” for plenty of thoughtful rap fans who see through their know-what’s-good-for-you deceptively controlling attitude. Also, there’s a sense that the conquest of women, always a staple in rap, has now taken on a more nefarious edge. As Julianne Escobedo Shepherd asked in SPIN’s “Sheezus Talks” roundtable: “When are rappers gonna stop dissing their rivals by telling them they fucked their women (“bitches”)? We’re not chattel.”

Frankly, there is a tendency for rap critics to hide behind our liberalism and entry-level sensitivity training when it comes to sexism and misogyny. First, by thinking that it’s acceptable to just acknowledge the problem and quickly move on (though very few rap writers do even that), or to entirely defer to female writers on the topic. In other words, playing mindful outsider while making sure not to dominate the discussion because, hey, we get it, and certainly don’t wanna be called out for mansplaining. But often, that decision smacks of passing-the-buck cowardice. Men should wrestle with these issues, as well.

To put it in dude terms: Male rap writers like myself should grow a pair and step into the conversation, even if it makes us look like dolts sometimes. For example, a counterpoint that needs to be addressed is what gets muddled when the conversation solely focuses on misogyny. Intentionally or not, songs about murder and poisoning the community end up being less subject to critique. It’s a construct that cannot hold when Rick Ross loses his sponsorship for rape raps, yet his rhymes about murdering young black men are given a pass.

Let’s stop hiding behind the “this is art” defense because it’s not that simple. One way to approach rap, as a fan who cares, is to realize that the rap songs you enjoy, maybe even the ones by your favorite rapping human right now, are products. And like products, they are first and foremost providing a service. Mostly, they are going to promote the lowest-common-denominator values of a population. Accepting this doesn’t mean we’re condescending to these songs or taking them less seriously, but let’s stop this pseudo-high-minded junk where we invoke art every time Kanye West or Gunplay tell a woman to suck his dick. It’s lazy and insincere.

It’s also worth considering how exactly we got here. See, radio rap is now controlled by major labels to such a degree that it seems as though saying hateful things about women is one of the few rote topics that rappers can get away with on the airwaves. Rap on the radio is no longer a voice of the streets. Gun and drug references are bleeped or turned into vague platitudes, when they appear at all. Gun and drug talk was never just amoral sloganeering in rap. It often helped call attention to the epidemic of violence in urban areas, reminding the comfortable that there was a pointless drug war still going on (“Black CNN” and rap-as-reportage and all that good stuff). But it is not a coincidence that journalistic details have been rubbed out of popular rap, finally. And it is not a coincidence that misogyny is still pervasive, either. As a result of the “cleaning up” of rap content, all that’s left is objectifying of women and lots of songs about buying lots of things.

Rap critics and fans should strive to acknowledge those moments when the music kicks back against misogyny. Eve’s Lip Lock is one of the most confident and adventurous rap albums of this year, and it was afforded little praise or attention. That’s mostly because the radio has its female rapper already with Nicki Minaj; she’s great, of course, but it’s 2013 and there’s no reason why there can only be one female rapper deserving of greater attention. The best guest verse on Chance the Rapper’s buzzed-about Acid Rap is from a female MC named NoName Gypsy on the song “Lost.” Gypsy raps from the perspective of a victimized young woman, yet affords the persona some agency and even touches on an under-discussed topic like the tendency for women to be medicated more frequently than men.

Earlier this month, DJ Mustard released the mixtape Ketchup. It houses some of the most innovative minimalism I’ve heard in quite some time. It’s also full of fuck-her-face shithead raps. But it also has two inspiring female rewrites. On “Straight Ryder,” R&B vocalist Candice turns Tupac’s “Ambitionz Az a Ridah” into a personal anthem of independence. “Get out my way or get knocked down,” she croons over a Mustard-ized take on that classic rap beat. On “LadyKilla,” female MC Cocc Pistol Cree raps about drugging a guy’s drink, then convincing him to pay her tab while she waits on an older gentlemen that she’s dating to die so she can get his money. That’s so much darker (and entertaining!) than any of Yeezus‘ bitter scenarios. It plays out like Quentin Tarantino penning a take-no-prisoners, revisionist flip of Rick Ross’ insensitivity (or just radio rap in general), yet it doesn’t seem like anybody was even listening.

Rap music clearly has a serious misogyny problem. Admitting that won’t lead to the elimination of the music altogether and it doesn’t mean that all other social issues have to take a backseat. But once the problem has been acknowledged, let’s don’t just leave the self-evident truth sitting there. Actually continue to think about this stuff. Too often, rap’s misogyny has been treated as a given. And that’s just as dangerous.