Perhaps it goes without saying, but the most culturally significant movie of the 2010s is The Avengers. There were many decades of superhero movies before the release of Joss Whedon’s 2012 box-office behemoth, and the move toward the stylish, ideologically mature comic-book flick had already been made with Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins and The Dark Knight in the previous decade. But The Avengers was the first to prototype the sprawling extended universe posse film, uniting a host of disparate characters from the Marvel mythology in one movie. The Avengers and the movies it inspired—both in and outside of Marvel—challenge the idea that a feature film should function as a standalone narrative work. Its sequels Age of Ultron and Infinity War require an extensive base of background knowledge from the characters’ previous stand-alone movies—and sometimes from the comic books themselves—in order to follow the story, or at least fully appreciate the stakes. Marvel’s Avengers experiment was nonetheless successful, partially thanks to the huge built-in audience, but also to the offbeat choice of writer and director: reliably clever Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Firefly writer Whedon, in only his second turn as a feature film director.

Avengers fever swept over Hollywood, as the film gained both critical and industry accolades and became the third highest-grossing movie in history, with a $1.5 billion box office haul worldwide. Not only did its success incentivize Marvel and DC toward making many more bloated franchise films, it helped justify and encourage the ongoing surge in gritty reboots and modernized reimaginings of all sorts. As the MCU continued to take over the box office, network TV, streaming services, and the internet, another monolithically profitable franchise—Star Wars—would also return, invested with a nostalgic sense of purpose and an over-ambitious slate of projects, all of which seemed to foreshadow many years of increasingly warped complications to George Lucas’original mythology.

The Marvel, DC, and Star Wars microindustries demonstrate the extent to which film and TV culture in the 2010s—more than ever before—was dominated by creators finding savvy ways to retell old stories, as the industry became increasingly devoted to the assumption that “existing IP” has a stronger inherent and quantifiable value than fresh narratives. The trend extended well beyond comic book lore, from The Jungle Book to Aladdin to Planet of the Apes to Shaft (yet again) to a hell of a lot of previously adapted Stephen King material.

Unranked and not intended as definitive, this list largely forgoes discussion of adaptations and tribute projects, and features few of the decade’s major summer blockbusters as a result. (There are exceptions, like Mad Max: Fury Road, which stands as perhaps the most inspired and subversive action film of the decade.) Here, we’re focusing on strong original stories that found broad audiences, inspired trends, spoke meaningfully to sociopolitical and cultural themes, or felt somehow emblematic of the spirit of the 2010s. These are 30 enduring, significant, and just plain great films from the last decade, as chosen and blurbed by the Spin staff.

See also: 30 Great TV Shows That Defined the 2010s

Winter’s Bone (2010)

Debra Granik’s breakthrough feature is probably best known today for launching Jennifer Lawrence’s career, but it should also be remembered as one of the great neo-realist films of the past ten years. Few directors have portrayed extreme poverty in middle America with more nuance. Winter’s Bone offers a devastating portrait of a dirt-poor community in the Ozarks with no infrastructure or government oversight, racked by meth lab explosions, domestic abuse, and petty crime. Like her debut—2004’s Down to the Bone, a C-budget film about the downward spiral of a coke-addicted housewife in upstate New York—Winter’s Bone portrays drugs as a means of escape for the down-and-out, whether psychological or economic.

Ree Dolly (Lawrence) is already the head of her household at the age of 17, struggling to feed her family and keep their house. As she sets out on a quest to find her father, Granik’s film turns into a gripping noir thriller, offering crossover appeal to audiences beyond the arthouse circuit. (It gained enough attention to secure four Oscars nominations, including one for Best Picture.) But Granik’s commitment to using real locations and non-actors, and immersing her central cast of professionals in the extreme locale in which the film is set, gives Winter’s Bone its unique power. It makes the film as immersive as the actors’ experience must have been. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Inception (2010)

Christopher Nolan has always liked puzzles. He spent the 2000s crafting tight, conceptual thrillers with riddles at their core, with Memento to The Prestige being the strongest examples. Even in his relatively straightforward Batman movies, the gambit is structural: Nolan can’t help but play around with timelines, mysterious flashbacks, and twist endings.

The most high-minded of Nolan’s films, Inception is also the densest, featuring unreliable protagonists, nested narratives, and paradoxical point points. As a result, the movie spends a significant amount of its runtime explaining how it works. In this world, shadowy international corporations pull the strings, and the minds of important business people and political leaders are prized targets. Dreams can be infiltrated, and secrets stolen via psychological espionage. Cobb and his crack team of infiltrators explore three layers of dreams-within-dreams, attempting to lead a young Robert Fisher (Cillian Murphy) towards a particular business decision by helping him repair his relationship with his late father. Cobb is seeking redemption from something, and the unknown event’s lasting psychological implications take the form of literal projections, interfering consistently with the mission he is supposed to be carrying out.

Nolan hones in on the intricacies of the dreaming process, but despite his meticulous explanations, the film still manages to inspire a sense of subjective wonder. We can argue about how cleanly the puzzle pieces fit together, but the scope of Nolan’s accomplishment remains staggering. No major Hollywood filmmakers are making blockbusters with this much conceptual ambition. In an increasingly Marvelized film landscape, Inception is a testament to what Cobb calls the “most resistant parasite”: the lasting power of an original idea. —WILL GOTTSEGEN

The Social Network (2010)

The Social Network, the unconventional Mark Zuckerberg biopic directed by David Fincher and written by Aaron Sorkin, got some flack at the time of its release for being a less-than-truthful account of Facebook’s rise to prominence and the lawsuits that resulted from it. But Fincher’s distinctive film does something more important than dramatize history. It evokes the feelings of jealousy, loneliness, and greed that, by some accounts, helped alienate the founder of Facebook from the people who helped him get to the top.

Jesse Eisenberg plays Mark Zuckerberg as a tightly wound ball of nerves and insecurity, simultaneously psychologically unraveling and creating a self-satisfied mythology for himself as Facebook snowballs in popularity. The film looks back on the company’s genesis from the context of depositions by the Winklevoss twins (Armie Hammer), who claim Zuckerberg stole the idea for Facebook from them, and his former best friend Eduardo Sauverin (played by Andrew Garfield). This frame allows the filmmakers to revisit the events that tore Zuckerberg and Sauverin’s friendship apart, including Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake) coming onboard as an early investor and seducing Zuckerberg by telling him everything he’s ever wanted to hear.

Fincher and Sorkin turned out to be an unlikely dream team. Few directors have made banging out code or clicking around an Internet browser as exciting to watch as Fincher. Sorkin has an acute understanding of the effect power has on people, both those who crave it and those feel oppressed by it. The best scene of The Social Network is the one in which Sauverin finds out that he’s been diluted out of Facebook’s shares, and Sorkin’s rapid-fire dialogue heightens the vitriolic intensity of the conflict. (The best anecdote about the making of the film is that Fincher asked Sorkin to read the script the way he hears it in his head, timed him, and used that time to dictate how fast the actors had to talk.)

The score from Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross—the duo’s first and best film project—is the icing on the cake. In his previous work with Nine Inch Nails, Reznor channeled anger and anxiety into a specific industrial rock sound, but adapting his sensibility to film scoring brought out a new side of his musical genius. The Social Network‘s varied soundtrack borrows elements from new wave, post-punk bands like Joy Division, and New York City underground music from the 1980s, helping to enhance the creeping sense of dread in Fincher’s melodrama. —ISRAEL DARAMOLA

Bridesmaids (2011)

As one of the monumental mainstream comedies of the decade, Bridesmaids proved for the umpteenth time that women are more than capable of carrying a summer blockbuster. Ultimately drawing a whopping $288 million at the box office, the movie introduced movie-going audiences to Kristen Wiig’s screenwriting and provided comedic titan Melissa McCarthy with a breakout role. Even more importantly, it features female comedians occupying the gross-out-comedy space producer Judd Apatow typically reserves for his cadre of manchild actors.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the film, however, is how adeptly it navigates the joys and complications of female friendship and the separation anxiety that results when one half of the partnership gets engaged. Like any chick flick, there’s a romance—and an adorable one at that—between Wiig’s adrift failed baker turned underemployed jewelry store sales associate and George O’Dowd’s cop character. But the real love story is the platonic one between Wiig’s character Annie and Maya Rudolph—Wiig’s former fellow Saturday Night Live cast member—as Lillian, the bride. Given how often women are either underwritten or relegated to the role of love interests or harpies in Hollywood comedies, it feels revolutionary to see women portrayed this multidimensionally.

Wiig’s character, in particular, grapples with abandonment issues, jealousy, a propensity to self-sabotage, nagging feelings of inadequacy, and class anxiety. One thing you almost never see in a rom-com is the protagonist worrying about money, since she usually lives in an absurdly spacious Manhattan apartment on a New York media employee’s salary. Bridesmaids breaks the taboo by having Wiig’s working-class background fuel the tension between her and Helen (Rose Byrne), the wealthy interloper who is competing with Annie for Lillian’s affections. Few shots in the movie are more effective than the tight closeup of Annie’s paltry retail paycheck amid discussions of the decadent bachelorette weekend in Las Vegas. —MAGGIE SEROTA

A Separation (2011)

Iranian auteur Ashgar Farhadi’s A Separation is among the most significant international films of the decade, and not just because of the noise it made among U.S. arthouse audiences or its Best Foriegn Film Oscar. Even in a vacuum, A Separation—an emotionally hyper-charged family drama that never ventures into sentimentality or leaps to easy conclusions—stands as a singular and monumental achievement.

A Separation nests a story about a housekeeper who loses her child to a tragic accident within another about a couple going through a divorce (or rather, fighting for the right to do so). Farhadi offers a multifaceted, contradictory portrait of every character he puts on screen. If our sympathies are naturally aligned with the couple—Nader (Peyman Moaadi) and Simin (Leila Hatami)—at the film’s outset, our allegiances become muddled as class double-standards and other complicating factors present themselves. Nader’s rival Hojjat (Shahab Hosseini) initially scans as a toxically insecure and controlling husband, but as Farhadi elucidates the ways in which Iranian society underserves and scapegoats people from his socioeconomic background, the character becomes harder to judge.

Most of the central arguments between characters devolve into elaborate litigations of blame. It is difficult to pinpoint which disastrous events we are meant to chalk up to fate and which are the products of a broken societal infrastructure. The film highlights many restrictive cultural norms that do not account for the needs of real individuals, and for their inevitable flaws. Farhadi leaves his devastating parable open to free evaluation and reconsideration, steering gently clear of directly subversive critique, which allows him to explore themes and paradoxes that a more aggressively didactic movie might have circumvented. A Separation challenges all of us to take a more empathetic view of the individuals with whom we are thrown into conflict in life, and to constantly interrogate the inherited principles and codes that inform our actions. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

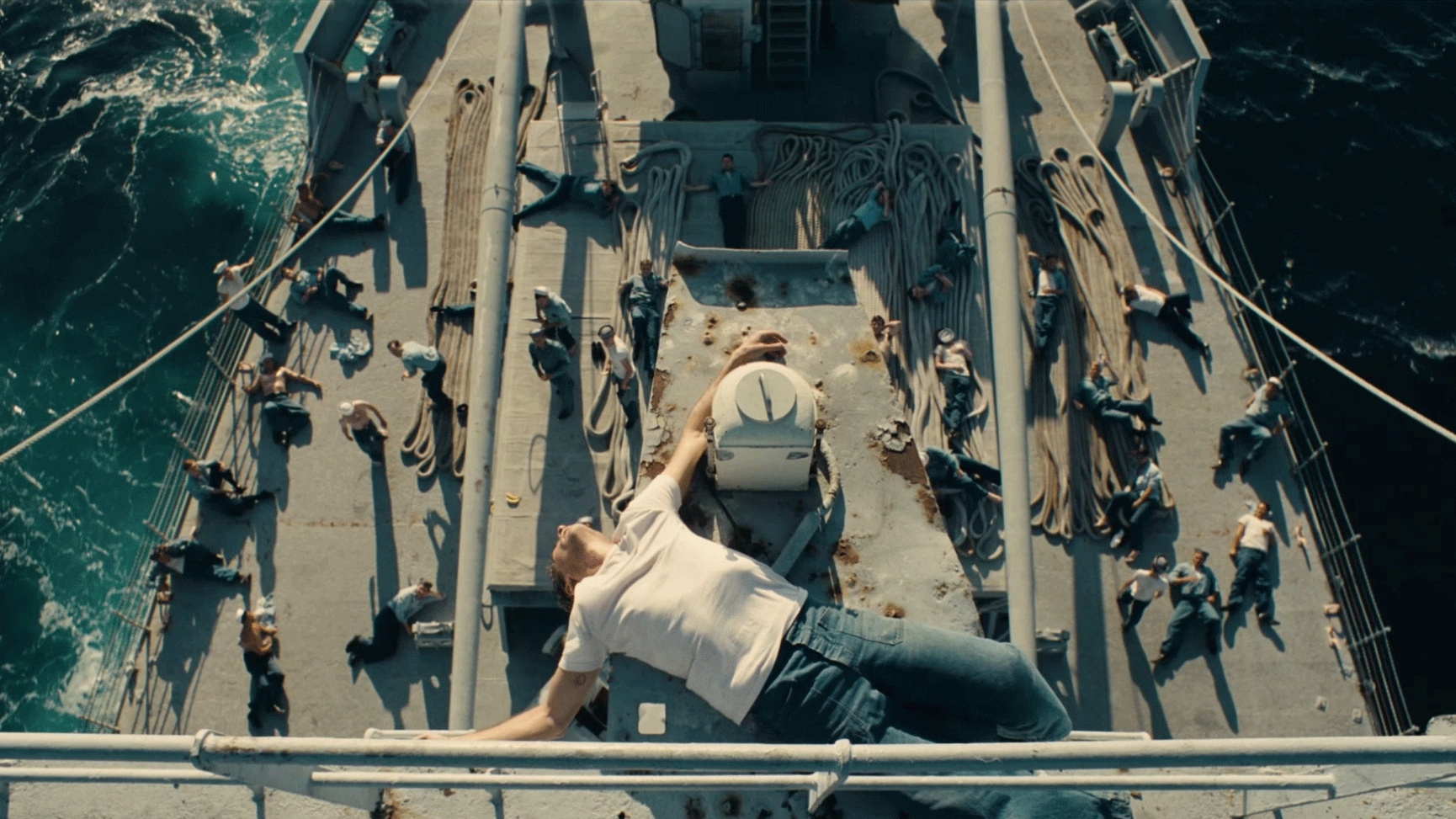

The Master (2012)

Any two Paul Thomas Anderson fans could spend hours arguing over their favorite of his films from the 2010s, but The Master has a lot to recommend it as his most enduring and apropos statement. As a story about a con man (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and an angry, misguided follower (Joaquin Phoenix) taken in by his manipulation, the film has even more resonance today than it did upon release.

Rewatching the movie in the second half of the decade, it’s easy to imagine Freddie, Phoenix’s mouthwash-drinking nightmare of American masculinity, as a representation of the silent and malcontented majority who empower our most prominent purveyors of snake oil. Lancaster Dodd, Hoffman’s charlatan character, is a proxy for L. Ron Hubbard, but he ascribes to a more genteel cult-guru business model than the Scientology founder. (The Master is just one of many great cult stories from this decade, from Holy Hell to The Invitation to Get Out to Wild Wild Country, to the non-fictional Scientology exegesis Going Clear.) Despite some parallels, Dodd’s methods of persuasion are distinctly non-Trumpian, combining a down-to-earth joie de vivre with a charismatic pseudo-intellectualism.

The Master offers an oblique retake on The Great Gatsby‘s central Nick-and-Jay dynamic from the perspective of a far more unreliable narrator. The film’s expressionistic cinematography and erratic pacing evoke Freddie’s constantly compromised state of mind and delusions of grandeur, with support from Jonny Greenwood’s seasick score, which—as with all of his soundtracks—functions like another character in the film. As the followup to his career-altering experiment There Will Be Blood, The Master showed that Anderson was intent on solidifying a new, wholly original voice for his films in this new decade, which would later include forays into different time periods and genres. The Master is both his murkiest and multivalent work—the one that most easily invites new interpretations with every rewatch. —Winston Cook-Wilson

Holy Motors (2012)

Holy Motors opens with motion. A man runs back and forth, as if he’s in a zoetrope, in a few crackling frames briefly looped between the opening credits. Another throws a brick at the ground, over and over. The title card fades in over an auditorium of shrouded heads, facing us as they face as the screen. A foghorn sounds.

The credits form a kind of mission statement for French filmmaker Leos Carax’s fifth and most ambitious feature. Fittingly, we spend the next two hours observing a man who is constantly in transition. Denis Lavant plays Monsieur Oscar, a Chaplinesque performer inhabiting various real-world roles over the course of a single day. Cruising through Paris with his faithful driver, he stops to play a homeless beggar, a disgruntled father, and a motion capture performer in an alien sex scene. Lavant also reprises his role from Carax’s contribution to the film Tokyo!, as a street leprechaun of sorts named “Merde.” He licks armpits, defiles graves, kills, and dies. The Agency employing M. Oscar keeps a tight schedule, and appears to have panoptic access to the city and its inhabitants. The line between performance and “real life” is often blurred; when Kylie Minogue shows up for an impromptu musical number, the line is erased entirely.

All speed and gesture, Holy Motors is as stubbornly committed to its elusive project as M. Oscar is to his, posing far-reaching questions about art, technology, and modern love without answering them. Moments of intense violence, sexuality, and grief pass by on screen before we’re able to fully digest them, making us feel constantly disoriented. Asked at one point why he does whatever it is he does, M. Oscar puts it simply: pour la beauté du geste, or, the beauty of the act. “Performance” is the bottom line for Carax and his characters, animate and inanimate, all of whom are being watched by the Agency, by passive onlookers, or just by the moviegoers themselves. —WILL GOTTSEGEN

The Queen of Versailles (2012)

Thanks to accidental good timing, Lauren Greenfield’s documentary Queen of Versailles was able to distill the state of the modern American economy in the lead-up to and immediate aftermath of the Great Recession into a haunting microcosm. It begins in the mid-2000s, trailing the Siegel family—led by the the computer-engineer-turned-model Jackie and her timeshare magnate husband David—as they attempt to build one of the largest and most expensive homes in the United States. The plans for the sprawling, 90,000-square foot Florida estate include gigantic custom-made stained glass windows, each costing six figures, and separate wings for the family’s children. After the recession hits, Siegel’s timeshare business, which relied almost entirely on the sort of reckless easy loans that triggered the crisis, is crippled, and construction on the family’s gargantuan dream house halts. Starting out as a reality-TV-like portrait of an obscenely wealthy family, The Queen of Versailles suddenly becomes a horrifying downward-spiral story that parallels the implosion of the global economy in the late 2000s.

Eventually, the Siegels, who had not been particularly well-prepared for the crisis but were rich enough to be insulated from actual suffering, decide to lay off most of their largely foreign-born staff, many of whom were supporting families in their home countries that they hadn’t seen in years or even decades. Interviews with their domestic workers provide a devastating glimpse into the international ripple effects of the meltdown. Another one of the Siegels’employees—the family’s limo driver—reveals that the millions he’d accumulated in local real estate are now worthless.

These moving testimonials are interspersed with plenty of moments of incidental visual poetry: the family’s half-built, indefinitely delayed mansion is reclaimed in part by nature, with grass and other plants taking over the driveway and other open areas, as is the massive house the Siegels already reside in. With fewer cleaners and nannies (they, of course, still employ several), dog shit and other filth accumulates indoors. One of the children’s pet iguana dies in its cage after being left without food or water. Ultimately, Jackie and her kids have to ditch the private jet and fly commercial to upstate New York for a visit with her family members, who still live in the same humble circumstances Jackie was raised in.

The film also includes clips of middle and working class families touring David Siegel’s luxurious timeshare condominiums, which they are assured are theirs in perpetuity as long as they make the necessary payments on time. These clips take on an increasingly unsettling quality as the film goes on: viewers can only imagine how their lives have been destroyed, and how much they could use their down payments back now. The timeshare company’s once-bustling call centers are shown empty, with most of the regular employees having been laid off, and a postscript to the film reveals that David was eventually forced to sell a majority share of his prized Las Vegas tower. (Earlier in the film, David brags that Donald Trump once complained to him about the brightness of the Vegas tower’s sign; later, he mentions that a potential bailout loan from Trump—surprise, surprise—never came through.)

The access granted to Greenfield at the beginning of filming, presumably under an assumption from the Siegels that she would present them in a complimentary light, helps invest The Queen of Versailles with an unusual power. We also don’t see talking heads retroactively discussing the cause of the financial crisis, or interviews with people who have lost it all after they have lost it all. Greenfield shows it all happening almost in real time, with admirably frank commentary along the way from the Siegels and their extended family and employees. We see the peak of their self-delusion, the disregard for common sense, and of course the decadence turning into squalor.

The film ends with the Siegels’life, and the world economy, still in chaos, but a quick Google search confirms that their time share business has since rebounded. (Wealth estimates should be taken with a grain of salt, but for what it’s worth, David’s is currently listed at $900 million.) Construction at Versailles has also resumed, and Jackie promises it will be finished by this fall. The renewed boom times haven’t protected the Siegels from the next major plague to strike America, though. In 2015, their daughter Victoria died of a drug overdose, a fact which Jackie has blamed in part on publicity from the film. Now, she herself is making a film about it: The Princess of Versailles. —TAYLOR BERMAN

Spring Breakers (2012)

In 2012, the prolific hip-hop producer Alchemist released a 12-minute single titled “Yacht Rock,” which juxtaposes smooth jazz and soft pop samples with raps about absurd violence and tasteless wealth. New York goons Action Bronson—in character as a spoiled banker’s son—and Roc Marciano show up to choke sharks, crash boats, and facilitate sex trafficking. The song is punctuated by clips of salesmen pitching gaudy new yacht features, seemingly ripped from an aspirational lifestyle program on some unknown cable channel. Near the middle, Big Twinz enters with a shrapnel growl that could shred the finest sails, rapping bluntly: “We on a yacht, celebratin’non-stop.”

Harmony Korine’s 2012 postmodern comedic thriller Spring Breakers might reasonably recall many different rap songs; after all, hip-hop culture is an integral part of its exploitative pop-art aesthetic. But for me, the movie feels like a cinematic version of Alchemist’s mini-epic, if it was being told from the perspective of the women on the yacht, and if they were secretly plotting to get revenge on the hustlers who brought them there. In Korine’s movie, his wife Rachel and three family-friendly child stars—Selena Gomez, Vanessa Hudgens, and Ashley Benson—play college students desperate to “get the fuck out” of their stale on-campus bubble. They decide to take a journey that has become archetypal for a certain subset of American adolescents: the spring break trip. Almost always clad in bikinis, Hudgens and Benson play the group’s devious rascals, Rachel Korine the down-for-whatever accomplice, and Gomez the church girl tempted to bite the apple.

The movie opens with its most iconic image: a slow-motion pan through a crowd of revelers hitting beer bongs to Skrillex on the beach. With scenes like this, Korine initially seems to be laying the framework for a warped comedy about teens coming of age through partying. But the armed robbery that yields the money for the girls’trip suddenly pushes the film into unfamiliar and more unsettling territory. James Franco shows up as a mob boss who looks like Riff Raff loves Scarface and Britney Spears; after bailing the girls out of jail, he enlists them as his posse of gun-slinging accomplices. The four girls’vacation turns into a voyeuristic tour of the criminal underworld in a South Florida community—one that is mindlessly exploited by frat stars for part of every year—and suddenly, Spring Breakers becomes a surreal gangster film.The film culminates in another shocking and illogical spree of violence that gives our protagonists the last laugh.

The eerie menace that lurks in the background of Spring Breakers, and in so much of Korine’s work, stems from the fact that his characters’motivations are often opaque; anything can happen at any time. In Spring Breakers, the writer and director creates an atmosphere that is both sensual and hostile. His camera explores the glistening surfaces surfaces of pools, assault rifles, and grillz. We might understand the movie as taking the glorification of violence and excess wealth in popular culture to some kind of nihilistic extreme. After all, our protagonists seem to ultimately fulfill their mythic vision of themselves—at least, the final two left standing are convinced they’re heroes. One thing is clear, though: the blacked-out Skrillex fans on the beach will never stop dancing. —TOSTEN BURKS

Frances Ha (2013)

Frances Ha is a film about living life with big dreams, and what happens when those aspirations come to an uncomfortable head with reality. Its titular protagonist is a struggling modern dancer (Greta Gerwig) who gets dumped by her boyfriend about five minutes into the movie, and is essentially homeless by the 15-minute mark. For moral support, she relies heavily on her best friend from her days at Vassar: the shrewdly ambitious Sophie (Mickey Sumner), who now works in book publishing, and has her shit a little more together than Frances. The quiet intimacy they share in the film’s early scenes amounts to something like a mother-daughter relationship, with Sophie even letting Frances sleep in her bed.

“Tell me the story of us,” asks Frances, snuggling up to Sophie like a wide-eyed child expecting her favorite bedtime story. Sophie plays along: “Again?” The story they tell together—because Frances can’t help but jump in—is one of professional, creative, and romantic success. In this imagined world, they have Parisian apartments, unnamable lovers, and endless “honorary degrees.” And though it already feels like a pipe dream, it only slips further away as the narrative progresses.

Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig’s script captures the precarious experience of being young and middle class in New York, negotiating the viewer through a sea of rich art kids and burnt-out English majors, irresistible faux-socialites and indelicate name-droppers. Frances’lingering questions are distinctly generational: Have I made it yet? Why are all these people having an easier time than I am? When do I graduate from the profoundly unglamorous present, and waltz into the future I’m really meant for—that New York City of our collective imagination?

Like Antoine Doinel of François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, who seems to have been a point of inspiration for Baumbach and Gerwig, Frances wants more, both practically and spiritually. But unlike Doinel, Frances ultimately finds a hard-won resolution, reconciling her greatest ambitions with the inauspicious truth of her personal and professional life. She makes some modest but crucial changes, settling into a gig teaching dance to children, repairing her increasingly strained relationship with Sophie, and finally landing her own apartment. There’s a sense, too, that she might even find love.

The film’s big reveal—that “Frances Ha” is really “Frances Halladay”—feels like a testament to the triumph of the individual spirit in a gargantuan, sometimes oppressive city. Like Lena Dunham’s influential series Girls, which premiered a few months before Frances’ festival debut in 2012, the movie distilled white urban millennial ennui into a genuinely transcendent artistic statement that should stand as a tentpole of coming-of-age comedies in the 2010s. Cautiously optimistic, Baumbach and Gerwig’s film suggests there’s always a reason to keep dreaming and smiling through the bullshit. —WILL GOTTSEGEN

Her (2013)

When Her premiered at the 2013 New York Film Festival, Siri was two years old. Instagram was still an app for grainy, faux-Polaroid photos, not an era-defining social network courting a dazzling visual aesthetic. Snapchat had just released its first iPhone app, Tinder was only available in a handful of major cities, and ASMR was still an obscure acronym relegated to the backwaters of kooky medical forums. Yet somehow, Spike Jonze’s fourth directorial effort anticipated the cultural dimensions of 2010s techno-capitalism with an uncanny accuracy—one that few sci-fi projects have achieved in the years since its release.

The effectiveness of Her doesn’t just stem from its appealing bright colors and Gore-tex-chic costume design. The movie also acknowledges how rapidly the role of digital communications is shifting and expanding in our everyday lives, and offers some astute theories about upcoming developments. In the film, Jonze foregrounds even the most banal, bleary-eyed interactions with smart devices. From the earliest shots of our protagonist—the wistful and somewhat anonymous Theodore Twombly, played by Joaquin Phoenix—viewers wade into an isolated world lubricated by headphones, video games, and ghostwritten personal letters.

Lonely, single, and struggling to finalize his divorce, Twombly finds the perfect outlet for his raw, overflowing emotions in Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), an “operating system” designed to be as much of a friend and companion as she is an efficient personal assistant. While the sensual scenes may be clunky and the dialog a little contrived, the film’s eagerness to explore the furthest limits of human-computer relations makes up for its kitsch factor. Samantha becomes a compelling remedy for Theodore’s alienation, allowing him to live a richer inner life without adjusting his daily routine—something his ex-wife brusquely criticizes when she says that he’s “madly in love with his laptop.” Ultimately, her indictment extends to nearly all of the film’s characters, who each find their own ways of escaping into vices that are both computational and social.

At its best, Jonze’s visually dazzling film moves beyond hackneyed man-vs.-machine hand-wringing, laying important groundwork for a more thoughtful approach to speculative fiction that’s as interested in exploring the nature of personal connection in the modern world as much as offering technological critique. Jonze also managed to import all of these ideas into the plot that resembles a romantic comedy, making Her an even stranger and perhaps more impressive achievement. —ROB ARCAND

Boyhood (2014)

In 2014, the third installment of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s autobiographical series My Struggle was released in English; the subtitle, translated from the Swedish, was Boyhood Island. It was the year that the books, which begin with a forensic account of the author’s coming of age, came to their greatest cultural prominence in the West. Around it, other notable works of quotidian autofiction or pseudo-autofiction popped up: this was also the year that Sun Kil Moon released Benji, that Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series became a phenomenon in the U.S., and that Ben Lerner published 10:04. It was an appropriate moment for Richard Linklater’s Boyhood, a sprawling bildungsroman of a movie about the coming of age of a Texas boy. Filmed over the course of 12 years, the film traced Mason (Ellar Coltrane) across seven different phases of his life, beginning in early elementary school and ending with the beginning of his freshman year at college at the University of Texas. Coltrane’s real-life experiences often dictated the direction of Linklater’s story, and most of the actors devised the details of their characters from their own life experience.

Despite its audacious scope, Boyhood feels modest. (Its budget certainly was, much of it seemingly reserved to fund the eminently recognizable, of-the-moment music cues.) We watch Mason-Coltrane learn to adjust to the world, trying to solidify and maintain a sense of self among rapidly changing circumstances. The film’s scenarios are usually small, specific, and simple—only occasionally explosive and never overwrought. When Patricia Arquette’s overworked single mother and Ethan Hawke’s semi-absentee charming slacker of a father proffer “wisdom” to Mason, it is a direct and believable outgrowth of their own experience as we have seen it transpire onscreen. We watch them earn their grey hairs, noticing things Mason might not have been able to understand at the time. Everyone is going through their own crises while Mason is learning to find his way; the movie is about him, but he is not the center of its universe.

In the 2010s, several landmark films got inside the heads of children. The first visionary epic of the decade was Terence Malick’s The Tree of Life, featuring virtuosic child acting that was much more powerful than its CGI dinosaurs. From there, films like Moonlight, The Florida Project, Eighth Grade, Call Me By Your Name, and We the Beasts offered subjective windows into the pre-teenage and teenage mind. But Boyhood‘s project remains unique within these ranks. It is neither a traditional story nor a shapeless indulgence; Mason’s trajectory across so many years seems instinctual, and is pleasantly resistant to tidy analysis. At the same time, the film offers us a documentary-like experience: an opportunity to watch the characteristics of a real person alter subtly (or extremely, around the time puberty kicks in) across their most active period of physical and mental change. And it all happens in just three hours. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

John Wick (2014)

What Keanu Reeves lacks in traditional acting chops, he makes up for with a gentle and stoic charisma. In additional to his looks, it’s this unwavering mien that has helped him remain a major star in Hollywood since the early ‘90s. Still, the unexpected 2014 action hit John Wick seemed to unlock a whole new level of action-hero potential in the former Speed and Matrix star, zeroing in on a new way to exploit his narrow but potent appeal. Reeves’eponymous antihero character—comically taciturn, unwaveringly committed to his bizarre missions—is the takeoff point of the finest action franchise born in this decade.

Directed by stuntman-turned-filmmaker Chad Stahelski, John Wick is a loud and expensive modern action movie like so many others, but the sensibility also feels like it taps into older and more playful cinematic traditions. In many ways, it comes across like a loving ode to the “gun fu” action movies of John Woo and takes cues from the more recent The Raid series. Aside from its base of influences, Wick‘s carefully fleshed-out and fanciful mythology also makes it stand out. In the New York of John Wick, hired killers and bounty hunters are part of a well-organized association with a convoluted system of rules. They have their own currency, doctors, retail, and transportation services, and bureaucratic cronies. Central to the network is The Continental, a hotel and central base for the criminal underworld that works to protect and rein in its members. It’s a clever plot device that injects a bit of humanizing mundanity into the lives of the movie’s motley cast of hard-knocks and murderers.

Yes, all of this is totally ludicrous, and that’s without touching on the primary point of conflict in the film: Wick begins his unsanctioned revenge spree because he is furious about a Russian thug killing his dog. But this absurdity helps the film and its sequels stand apart. Things are possible in the Wick movies that wouldn’t be in action movies with more banal and self-serious plots. The world-building also heightens the stakes in the films’well-crafted action sequences, causing you to become invested in a way that might feel impossible in a movie starring a more boilerplate Jason-Bourne-type leading man. Reeves’commitment to the physically demanding role, even as a man in his fifties, also helps these scenes’intensity. He performs his own stunts, punishes his body in ways that are almost scary, and murmurs threateningly; to celebrate John Wick is really to celebrate Keanu Reeves. —ISRAEL DARAMOLA

It Follows (2014)

The best horror movies revel in ambiguity, and It Follows, which stands as one of the decade’s best arthouse genre films, leaves open a wide range of possible interpretations. A mysterious entity hunts a group of young adults in a decaying working class suburb on the outskirts of Detroit, with its reign of terror beginning when Jay (Maika Monroe) contracts an unidentifiable disease on what seems like an auspicious date with a dude using the assumed name “Hugh.” Director David Robert Mitchell offers no origin story for the movie’s central deadly force—that is, the sexually-transmitted shape-shifting “it” that pursues the infected host and kills them before they can pass the disease to a new victim, like a deadly game of conjugal hot potato.

Most contemporary horror films are in some way referential, but Mitchell avoids winking into the camera and foregrounding his points of inspiration. In a sense, It Follows is a spiritual successor to John Carpenter’s Halloween, complete with chilling synth score and low body count (just two kills!) Even the main character’s name, Jay, is a nod to Jamie Lee Curtis, the original scream queen. But Mitchell aims to construct a unique, collage-like universe rather than open a time capsule. Despite its faded aesthetic and early splatter-film reference points, it’s impossible to nail down when the action in It Follows is supposed to be taking place. Among other things, a recent car model amid a sea of shitty old beat-up used sedans and a quick shot of a Kindle-like e-reader confuse initial suspicions that the movie is intended as a ‘80s period piece. The scrambled reference points make Mitchell’s aesthetic all his own, transforming the film’s inherent nostalgia into something more subjective and unsettling. —MAGGIE SEROTA

Mad Max: Fury Road (2014)

No accounting of the decade’s cultural works that deal with our potential future on this planet would be complete without George Miller’s exhilarating but sobering resuscitation of his Mad Max franchise. Mad Max: Fury Road is such a titanic achievement in terms of the literal act of filmmaking that it will always be remembered most for its technical accomplishments, but it also offers much more: an affecting peek into a world where the fabric of society has been undone by an absence of resources. In Fury Road‘s vast desert wasteland, everybody is fighting for something: water, milk, blood, bullets, gasoline, a simple recognition of one’s humanity. But the focus is on the battle being waged by Charlize Theron’s Furiosa in her search for a utopia she remembers from childhood. That Miller dubs it “the Green Place” makes the allegory obvious.

Furiosa’s hunt for this fertile wonderland is an escape in more ways than one. In tow are the five young wives of Joe, the grotesque dictator who lives high above his sunbaked, sand-covered populace with a rainforest in his lair; when the starving hordes gather at the bottom of his fortress begging for water, he turns the spigot on for about as long as it takes to wash your hands. Joe’s pursuit of Furiosa and his wives—well, one in particular—triggers a clash that Miller renders as a race across the desert, and against time. The result is a series of scenes that reimagines the Fast and Furious franchise as a grindhouse film, as Furiosa’s big rig snakes around the dustbowl, fending off armored attackers, leaving explosions and wreckage in its wake. It is a thrilling spectacle—in another context, it could be a sport in this chaotic, ruthless world, history bending itself back towards the days of the gladiator. But ultimately it is a desperate one, driven simply by a desire for basic human rights in a world that can no longer provide such a thing. Furiosa kills Joe but it feels empty; the Green Place is swampland, a mud pit pocked with the rotted husks of trees. The dictator, meanwhile, lived a life of gluttony and died quickly. —JORDAN SARGENT

Magic Mike XXL (2015)

Magic Mike XXL begins three years after its predecessor ends, with an update on the titular Mike Lane (Channing Tatum), who isn’t doing as well as fans might have hoped. The custom furniture business he long dreamed of building is now up and running, though not successfully enough; we quickly learn that he can’t afford to provide health care for his one employee, who will have to quit soon. We also learn that he’s single (no longer burdened by Cody Horn’s character or her awful performance in the original film). Mike spends a day partying with his old group of male stripper buddies, who are trying to figure out what to do now that their leader Dallas (Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike) has abandoned them. They have vague plans for a road trip to a competition in Myrtle Beach. That night, Mike hears Ginuwine’s “Pony,” a staple of his old stripping routine, on the radio, and the siren call of his relatively simple past life as a male entertainer proves too much to resist for the budding entrepreneur. Just like that, the ridiculous plot is on, all real world concerns are abandoned, and Mike and the gang are off to South Carolina.

What follows is 100 minutes of unrepentant fun. The crew stretches what should be a nine-hour road trip from Tampa to Myrtle Beach into an epic three-day voyage. Along the way, they shed the baggage from their everyday lives—literally in one scene, as they toss their old costumes out of the FroYo truck they’re inexplicably riding in—and embrace the exhilaration of the moment, of the planning and choreography, and then, finally, of their performances. Those performances are as fantastic as any in the first film. Tatum, this generation’s Gene Kelly, leads the way and is excellent as always, but Joe Manganiello, as the aptly titled Big Dick Richie, steals the show. (In a just world, his dance in a gas station alone would have earned him a Best Supporting Actor nod). There are, of course, notable plot events—a crashed van, a squabble over a girl, new love interests, and so on—but they all exist as excuses to push the movie forward to the next dance routine or at least to the next party.

Unlike Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike, which—assless chaps aside—was weighed down by its attachment to realism, Magic Mike XXL, helmed by frequent Soderbergh collaborator Gregory Jacobs, exists purely as a vehicle of escape. The unrelenting focus on surface-level pleasures eventually becomes its own sort of profundity, leading to one of the era’s most deeply entertaining films. Traditionally essential components, like plot and character development, don’t matter here. What’s important is the bliss of the performance and everything that surrounds it: not just for the film’s audience, or the women in the film watching the strippers dance, but for Mike, Big Dick Richie, and the rest of the crew themselves. For them, this trip represents a break from the everyday anxiety about their future. Neither Mike nor Soderbergh’s film has any illusions about the fleeting nature of such a reprieve, no matter how fantastical and successful the routines become. The movie ends, just as the three-day road trip does, with Mike watching fireworks explode over a beach, his friends all around him, happy but knowing that this moment is over. It’s back to the real world now. —TAYLOR BERMAN

The Witch (2015)

In the world of horror films, no production company’s imprimatur has been quite as unmistakable as A24’s in this decade, even while factoring in the significant work of the prolific Blumhouse Productions. A24’s 2015 acquisition The Witch, directed by Robert Eggers, is exemplary of their favored filmmakers’ethereal and often metaphorical approach to the genre. Eggers, an obsessive production designer and early American history fanatic, wanted to tell a weird tale about zealous early 17th-century colonial Puritanism, and decided to funnel his inspiration into a genre film in hopes of accessing a wider audience. It worked: Eggers’incredibly strange debut feature was served up to some multiplexes as part of its limited release, surely pissing off and rattling viewers expecting a more conventional Friday night horror flick.

Coming across like a Nathaniel Hawthorne short story recast as high-end Hammer horror and dipped in bad acid, The Witch represented the best-case scenario when it came to A24’s weird experiments in terror. Eggers’plot was a downward spiral story that zigzagged wildly during its descent, delving into realms that the director refused to clarify as either reality or fantasy. Its characters’language was sometimes as dense as Shakespeare’s, and the depth of Eggers’period research was almost distractingly apparent. But these elements were no more suffocating than the film’s claustrophobic action and mise-en-scène. The Witch takes place almost entirely in a hut, a tiny stable, a rotten field, and a non-descript patch of nearby woods. The players are a small and stoic family for whom Christianity functions primarily as an excuse for self-punishment. The film’s biggest provocation is its twist ending, which explodes implications that are only hinted at during the rest of the film, angering those who take it literally and delighting those who assign it a more symbolic significance.

A24 would go on to produce a number similarly high-concept horror movies by younger directors in the following two years, including It Comes at Night, Green Room, and The Blackcoat’s Daughter. Another breakthrough came with Ari Aster’s horrifying Hereditary, a major box-office breakthrough for the company in 2017. This year, Aster’s follow-up—the folk-horror epic Midsommar—seemed to deliberately tip its Swedish bonnet to The Witch in its transcendent final minutes. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Hunt for the Wilderpeople (2016)

The dominant strain of mainstream kids movies these days feels engineered in a lab to trigger pre-approved and powerful emotions in children and adults alike, providing cookie-cutter lessons parents can use to assuage their guilt over allowing two hours of mindless screen time. Just try watching a beloved neo-classic of the genre like Coco and not sobbing for at least half of it. (The lesson of Coco is to remember your loved ones long after they die and also, I guess, that even the most evil plagiarists can thrive in the afterlife, unless a meddling child saves the day.) This fine-tuned, audience-tested mass manipulation makes sense when you consider how profitable these films have to be, and that’s okay. As far as these sort of tentpole movies go, the recent spat of Pixar films have all been technically very well-made, and in terms of quality and respect for their audiences, they’re light years ahead of their rival in family mass entertainment: the largely cursed Marvel franchise. That said, they still have about as much spiritual heft as your average Nike commercial.

On the other hand, there’s a film like Hunt for the Wilderpeople. Written and directed by Taika Waititi, and based on Barry Crump’s novel Wild Pork and Watercress, Wilderpeople follows 12-year-old Ricky Baker (the fantastic Julian Dennison), a “real bad egg” living in foster care who was abandoned by his mother and adopted by Bella (Rima Te Wiata) and “Uncle” Hector (Sam Neill), an older couple living on a farm near the New Zealand bush. Without getting into too many spoilers, Ricky and Hector, along with their dogs Zig and Tupac, find themselves on the run in the bush as an increasingly absurd number of police and child welfare service agents chase after them. The cantankerous Hector and rambunctious Ricky initially resent each other but eventually become close out of necessity (surviving for months in the bush is no easy feat) but also out of a shared love of mischief, a distaste for authority, and a sense of mutual mourning.

Waititi understands as well as any filmmaker the importance of balancing adventure and humor, both in relatively smaller films like this and in larger blockbusters. (The Marvel films are only largely cursed thanks to Waititi’s Thor: Rangarok, a clinic on how to make a fantastic big-budget comic book movie.) Wilderpeople‘s themes of loss and abandonment could easily drift into twee sentimentality if Waititi’s chaotic comedic sensibility weren’t so finely calibrated. We—just like Hector and Ricky—can’t be sad for long when we have to reckon with ridiculous car chases, wild boar attacks, insane bushmen, and the Terminator-like persistence of a George W. Bush-paraphrasing child welfare officer named Paula (Rachel House). It’s a perfect example of what a kid’s movie should be: full of mischief and fun, with an earned message of resilience that never once feels cloying or pedantic. —TAYLOR BERMAN

Moonlight (2016)

The title of the play that serves as the inspiration for Barry Jenkins’2016 film Moonlight—In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue—perfectly evokes the bittersweet, dream-like tone of the movie. Set in Miami, Moonlight is a complex and heartbreaking coming-of-age story which offers snapshots of its protagonist Chiron during three different and pivotal stages of his life: childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Throughout Chiron’s maturation, we see him struggling with his sexuality while being bullied both by his peers and his drug addict mother Paula (Naomi Harris). However, he develops a touching friendship with a neighborhood dealer named Juan (Mahershala Ali) and his partner Theresa (Janelle Monae), and during his time with them, he seems to feel worthwhile and free to be himself.

Moonlight has many harrowing moments, but Jenkins never defaults to a cliched, torture-porn-like portrayal of life in lower-class black America. The writer and director offers a sensitive and nuanced perspective on life in Liberty City, offering a meaningful context for its scenes of violence. Moonlight was labeled at the time as a movie about a gay black man’s coming of age, but Chiron’s struggles with his sexuality are merely one aspect of his crisis of identity, and the film’s larger exploration of Black masculinity. For much of the movie, Chiron is unsure of everything about himself because his environment has dictated so much of what he believes he is supposed to be like. By the time we reach the film’s finale, the real victory is the fact that he finally feels able to say how he feels instead of keeping it bottled up.

Of course, Jenkins’gorgeous visual poetry is a large part of what makes Moonlight so distinctive. He creates a beautifully glazed, sweaty vision of Miami—towering palm trees, tricked out cars, and endless lonely highways—that feels like a love letter to the city, and Florida more generally. He also uses light expertly, framing his actors’faces in ways that enhance their pain and vulnerability. In the scene in which Chiron asks Juan and Theresa about his mom’s drug use, Mahershala Ali’s face says more than anything in the script. The way in which Jenkins’camera captures Juan’s discomfort and heartache during that exchange results in the film’s most powerful moment. —ISRAEL DARAMOLA

Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping (2016)

In the second half of the 2000s, Andy Samberg taught network television the concept of “going viral,” thrusting Saturday Night Live into its future existence as a well-funded YouTube channel that also happens to broadcast on NBC. Eventually, his comedy group The Lonely Island cemented itself as one of the great breakout successes in the show’s long history, using its 2005 Digital Short “Lazy Sunday” as a launching pad for a full-fledged musical act that hit the pop charts with parodies featuring guests like T-Pain, Akon, and Kendrick Lamar. SNL has birthed feature films out of far less than this, and so a Lonely Island movie was inevitable. It seemed like an obvious on-ramp to wider post-TV stardom for Samberg, who the group originally existed to elevate when it was just an experiment hatched by three friends who were still low on Lorne Michaels’list of priorities.

The group’s eventual film, 2016’s Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping, ended up arriving years after the group’s commercial peak in the early part of the decade. All of the group’s members had since become respected actors, writers, and directors in their own right, and Popstar demonstrates the way in which their skills had only been sharpened since the days of “I’m On a Boat” and “Dick in a Box.” It is one of the best comedies of the decade—a perfectly smart-dumb satirization of a time in history where the pop-culture-industrial complex was supporting doofuses like Justin Bieber and Macklemore. The latter artist, who is borderline-forgotten now, takes the brunt of one of the film’s best gags: a new single from Samberg’s character Connor4Real innocuously named “Equal Rights.” The track is a brutal riff on Macklemore’s 2012 single “Same Love,” which opens with the rapper explaining that he thought he was gay as a kid because he was good at drawing, but is actually straight. Connor4Real’s song takes Mackelmore’s weird distancing and blows it into a deranged, frenzied homophobia, which is much closer to how lots of gay people took “Same Love” than Macklemore would like to think.

Within the context of Popstar, the song highlights the deep insecurity that motivates Connor4Real: a fear of being revealed as a talentless prop. This pushes him toward pursuits like teaming up with an appliance brand that blasts his music every time a homeowner opens his fridge and attempting a magic trick that leaves him naked on stage. It’s the latter bit which begets the film’s most pointed and piercing parody: a version of TMZ called CMZ where a bunch of airheads, led by Will Arnett as Harvey Levin, one-up each other’s maniacal but hollow laughs while sipping from increasingly large coffee cups. Popstar has the right targets, and does not spare them. —JORDAN SARGENT

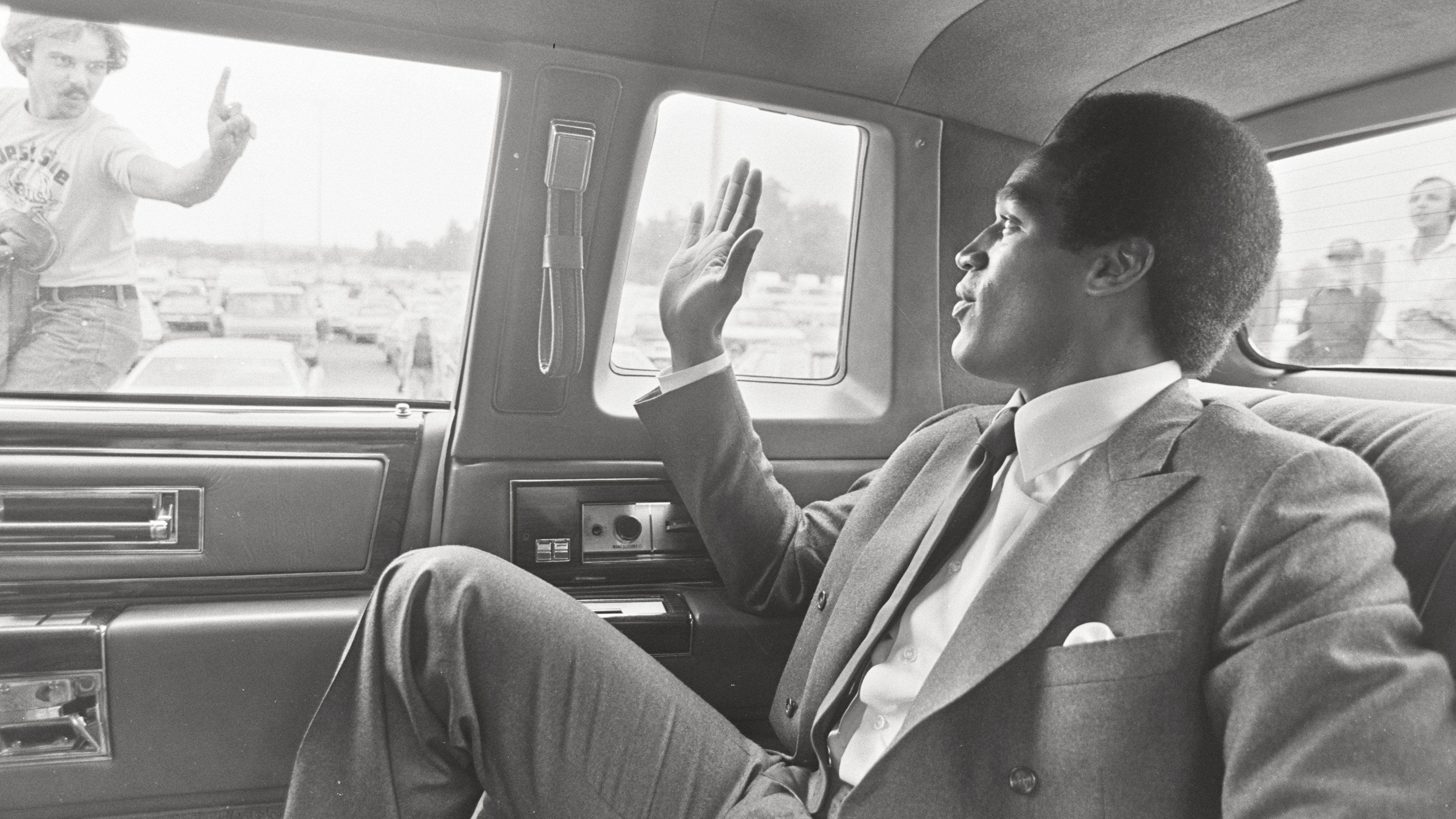

O.J.: Made in America (2016)

From the beginning, the O.J. Simpson trial was as much a cottage industry as a criminal proceeding, crawling with opportunists and talking heads—some of them working for the prosecution or defense teams—who were acutely aware of what all the available television air time could do for their bank accounts. This phenomenon was chronicled at the time by The New Yorker’s Jeffery Toobin, who commented on this unprecedented symbiotic relationship between the press and justice system while also participating in it. His book on the case, the wonderfully written The Run of His Life: The People v. O.J. Simpson, was the basis for Ryan Murphy’s scripted series of (almost) the same name, which reopened the O.J. content factory in 2016 to great fanfare.

Both the book and the show offer something different to consumers fascinated by the legendary trial. The former is an insightful, granular analysis of why the case unfolded as it did; the latter offers a searing and stylized look at the individuals who became enmeshed in one of the most highly scrutinized spectacles in American history. But neither has the scope nor the impact of O.J.: Made in America, a six-part, eight-hour exhumation by ESPN that would go on to win an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. Unlike Toobin and Murphy’s examinations, O.J.: Made in America argues that the Simpson trial was no mere confluence of events, but rather a calibrated collision of history with roots in nothing less than the original sin of this country.

The film lays out a timeline that begins in the mid-20th century, when Jim Crow and the Second Great Migration brought Black residents of states like Louisiana and Georgia west to cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles. Many who flocked to L.A., in particular, expected to be freed from racial persecution in a land of sunshine and palm trees; what they found instead was a police force that was regressive and racist to its core. When Simpson debuted for USC in 1967, quickly establishing himself as maybe the greatest running back anyone had ever seen, the city’s black populace had been locked into a cycle of oppression under the LAPD. Elsewhere in America, athletes like Lew Alcindor and Jim Brown were contemplating what their role in the nationwide fight for racial equality could, and should, be. Simpson, though, viewed his race only as a burden, one that could be shaken off as easily as a linebacker’s tackle as long as he performed on the field and stayed quiet while off of it. Across the documentary’s half-dozen installments, director Ezra Edleman lays out how Simpson, an entitled schmuck and unrepentant domestic abuser, would end up the beneficiary of a just but misapplied takedown of the LAPD’s entire rotten history—the wrong man at the right time.

O.J.: Made in America is also the only high-profile piece of O.J.-related entertainment to expose his life after being found not guilty. Simpson escaped to Miami to protect his assets under Florida law, living a dark and lonely existence, subsisting on the last dregs of his notoriety and surrounded by the types of hangers-on who would find it cool to be seen with a washed-up celebrity accused of murdering his wife. Simpson, recently released from Nevada prison after a bizarre robbery attempt, still finds himself in much the same place. You can go on Twitter to see him thirsting for retweets—a man who escaped a lifetime sentence but nonetheless locked himself in a prison of his own creation. —JORDAN SARGENT

Toni Erdmann (2016)

A comedy epic is a rare thing, and (with apologies to Mr. Apatow) a great one is even harder to come by. German writer and director Maren Ade’s wildly inventive second feature, 2016’s Toni Erdmann, fulfills both criteria. A rambling saga about the strained relationship between the comically overworked German business consultant Ines (Sandra Hüller) and her eccentric music teacher father Winfried (Peter Simonischek), it elicits tears at its funniest moments and remains empathetic even in its most cringe-worthy scenes.

Ade offers a cynical view of modern industrial greed and millennial amorality, but the character who puts the filmmaker’s message across is incapable of finger-wagging or self-serious proclamations. Winfried, who has a habit of inventing new personas for himself, disguises himself as a mysterious high-powered consultant named Toni Erdmann, donning a ridiculous mop-like wig and fake teeth and tailing Ines to restaurants, clubs, and dinner parties. He watches his daughter twist herself in knots for the benefit of thankless bosses, and does anything he can to break her paranoid focus and help her rebuild her sense of self-worth.

Ultimately, though, Erdmann is much more than a didactic Scrooge story. Ade shows tenderness for not only to her central pair of characters, but also for the worst businessmen of the bunch—deeply misguided, incapable of self-reexamination—and the objects of their exploitation. The movie features a staggering number of indelible set pieces, full of beautiful humanity and striking perversity in equal parts. A sexual liaison involving a petit four offers an image that is both absurd and inspiring, a hilariously protracted nudist dinner party is a major moment of cathartic release, and a ludicrous Bulgarian bear costume somehow manages to provoke the worst waterworks. You’d be hard-pressed to find a more charming movie made this decade. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Personal Shopper (2016)

Oliver Assayas’haunting and irresolute “ghost story” Personal Shopper is the most unusual case study of the millennial condition you’ll find on this short list. Our first impression of jet-setting personal assistant Maureen (Kristen Stewart) is how lonely her life seems to be. She goes in and out of the most chic shops in Paris and London, trying on and buying clothes on behalf of a client she is barely even permitted to see. At other times, Maureen tries her hand at being an amateur medium, boning up on best practices by looking at YouTube videos. She is struggling with the loss of her brother, with whom she was very close, and attempting to communicate with him in the afterlife.

In the midst of all this, a stalker of sorts starts pursuing her, at least on her personal devices. In one of the most singular sequences I have seen in a film within the past few years, Assayas creates tension through a long sequence of scenes solely through the use of iMessage threats. Maureen escapes into her phone or laptop many times throughout the film, searching for answers and new ways to communicate or express herself. We learn much more about her from her digital activities than from her disaffected and self-consciously cool IRL demeanor; when she is finally forced to face reality, it’s no longer clear what is a fabrication and what isn’t. —WINSTON COOK-WILSON

Read our year-end 2017 film essay “Ingrid Goes West and Personal Shopper Were 2017’s Best Films About Being Online“ here.

Call Me by Your Name (2017)

Luca Guadagnino’s tale of a brief but intense romance between the precocious teenager Elio and the self-assured grad student Oliver (adapted from André Aciman’s 2007 novel of the same name) was perhaps the decade’s most boldly sensual piece of filmmaking. Elio and Oliver meet in the summer of 1983, on vacation in northern Italy. They spend their days discussing big ideas, playing and listening to guitar and piano, sitting by pools and swimming holes, riding bicycles down cobblestone roads and dirt paths. In Guadagnino’s previous feature A Bigger Splash, an attempt at this sort of languid and idyllic existence is doomed from the start: attraction sours into jealousy, and old tensions boil into violence. But for Elio and Oliver, the usual rules and consequences are suspended, at least until summer is over. Oliver shows no concern for the woman back home who will later become his fiancé; Elio’s parents—who are also Oliver’s employers—seem similarly unperturbed by this relationship between a boy on the brink of manhood and a man just on the other side of the threshold.

The timing is important: as several critics have pointed out, Call Me by Your Name‘s early-’80s setting places it near the outset of the AIDS crisis, though the film never makes direct mention of the disease. Beneath the beautiful sunkissed bodies, there is an elegy for the lost utopia of youth and the unrealized possibilities of a world unravaged by an epidemic that would nearly wipe out an entire generation of gay men. Between Oliver and Elio, love and pleasure are the only things that matter, and death may as well not exist. In the face of darkness, Call Me by Your Name dares to celebrate desire—specifically queer desire—not as a pathway toward some greater fulfillment, but as an essential pursuit unto itself. —ANDY CUSH

Get Out (2017)

In the age of endless remakes and reboots, comedian-turned-director Jordan Peele established himself as an exciting and unique filmmaker with just one movie, based on a socially resonant original story. With his debut feature Get Out, he set out to make, as he once put it, a kind of “horror-thriller that’s never been made before.” He accomplished this, and landed an unexpected box office smash, by carefully constructing an incisive modern-day allegory about the gentle tyranny of benevolent racism—the kind quietly practiced by white suburban NPR listeners all over America. Taut, exhilarating, repulsive, and hilarious, Peele’s film deserves to be ranked among the formative “social thrillers” that helped inspire it, from Rosemary’s Baby and Night of the Living Dead.

If movie goers were surprised that a comedian could craft such a gripping and haunting film, they shouldn’t have been. If comics and horror writer/directors understand one thing, it’s timing. Every beat in the script of a good scary movie—every jump scare, reveal, and kill—is planned with surgical precision, and comedians consider rhythm, tempo, and pacing while writing the most effective version of a joke. Plus, Peele had already demonstrated his knowledge of the horror genre several times over in the various Key & Peele sketches that sent up tropes from vampire, zombie, and torture-porn flicks. It’s hard to write a good parody without intimate knowledge of and keen insight into a genre.

Peele’s adeptness as a filmmaker also comes through in his casting choices and the ways he exploits the strengths of the members of his varied ensemble, which consists of a healthy mix of industry veterans, newcomers, and comedians making their first foray into the horror genre (Lil Rel Howard, most notably). Daniel Kaluuya’s star turn took him from being a relative unknown to an Academy Award nominee. Peele also brilliantly weaponized Bradley Whitford, an actor best known for making white liberals feel morally righteous via the countless Aaron-Sorkin-penned monologues he delivered on The West Wing. —MAGGIE SEROTA

Read our 2017 review of Get Out here.

First Reformed (2017)

Writer and director Paul Schader’s First Reformed provides an urgent dramatic context to examine an issue whose importance to ours and all future eras which is impossible to overstate. Ethan Hawke plays Reverend Ernst Toller, the pastor of a small and sparsely attended historic church in upstate New York, who spends his days reading, fighting for funding from the church’s slick owners, mourning the loss of his son in the Iraq War, and drinking whiskey. When a young and pregnant parishioner named Mary asks him to counsel her husband Michael, an environmental activist whom she fears is about to commit some sort of radical violence, Toller obliges.

The scene in which they first meet glows with formal accomplishment and ripples with moral force. Philip Ettinger delivers a brief but indelible performance as Michael, who is unwilling or unable to close himself off to the raw truth of climate change, the way many of us do in order to maintain the sanity and stability of our everyday lives. He speaks of crops withering, continents flooding, societies falling into anarchy, comrades dying, children growing up in a world that would be unrecognizable to their forebears. He gives other small indications of the storm brewing within him: fidgeting, stuttering, a stare that could put a hole through a wall. Toller uses every strategy he knows to talk Michael down—to convince him, ultimately, that it’s worth bringing his and Mary’s baby into the world, and being alive to see the baby grow up. We understand immediately that Michael isn’t buying it, and eventually that Toller isn’t, either.

For the reverend, the encounter with Michael sets off a crisis of faith in God and in humanity, leading him down a path of alienation and rage that clearly recalls the arc of Taxi Driver, Schraeder’s first screenplay. (“At some point, I realized that the poltergeist of Taxi Driver, of Travis Bickle, had slipped into the room and as watching me,” Schraeder has said of writing First Reformed.) There is one key difference: the anger of Taxi Driver is nihilistic, while First Reformed’s righteous fury is humanistic. After watching the former, we might ask ourselves what circumstances could drive people like us to behave in the manner of a person like Bickle. After watching the latter, we might look around and wonder why we haven’t already strapped our torsos with explosives and barbed wire.

The power of Schraeder’s unhinged, expressionistic, and occasionally polemical film lies in that question. Most viewers will share Toller’s conviction that the stakes of global warming are life and death, but few if any will follow that belief to the same conclusion as him. Is he crazy, or are we? And if his response to our situation is inappropriate, what might an appropriate one look like? —ANDY CUSH

Minding the Gap (2018)

Few filmmakers have closer access to their subject matter than Bing Liu, the young director of Minding the Gap, a startlingly poetic documentary about skateboarding, domestic violence, racism, and working-class malaise in his hometown of Rockford, Illinois. Liu trains his camera on himself, his close friends, and their families, and he augments the film’s new footage with an archive of tape he shot in adolescence as the resident videographer in his local crew of skater kids. This sort of intimacy between documentarian and subject can be a powerful incentive toward elision of uncomfortable details: It would be easy to edit out the ugliest parts of an interview when the person you’re questioning is your own mother, as in one of Minding the Gap‘s most unsparing and memorable scenes.

But Liu never looks away. The film’s turn comes when he learns, unintentionally, about behavior from one of his characters that reinforces the notion of abuse as a trauma that replicates itself across generations. Liu has since spoken publicly about the “moral crisis” this revelation provoked in him, and as you watch, you feel some sliver of the overwhelming anxiety he must have felt as a filmmaker and a friend. Onscreen, he proceeds with clarity and empathy, indulging neither in high-handed judgement nor easy equivocation. His resolve allows Minding the Gap to probe convincingly at several of the central issues of our current American crisis. His eye for the balletic grace that his friends possess as skaters also provides the film with a note of cautious optimism. In any circumstances, Minding the Gap suggests, people will find ways to create their own beauty. —ANDY CUSH

Annihilation (2018)

When we meet Lena (Natalie Portman), the biologist at the center of Alex Garland’s psychedelic science fiction film Annihilation, she’s lecturing a college class about cell division. The process of one becoming two, she explains as cells divide onscreen, is fundamental to the propagation of life on Earth, but also to death. These are cancer cells we’re watching, it turns out, turning a body’s normal process of growth and repair against it until it breaks down entirely. Lena soon finds herself whisked out on a secret government expedition into Area X, a quarantined zone where a mysterious contaminant is causing the environment to behave in ways that undermine our normal understanding of such divisions and dualities. A deer has flowers on its antlers, and seems to move in tandem with its companion as a single being. People turn into plants. An alligator’s teeth grow in rows like a shark’s.

Lena resolves to enter Area X in part out of a sense of duty to her husband, who is the only known survivor of all previous expeditions there; recently, he has returned home severely diseased and emotionally unrecognizable. Over the course of Annihilation, we learn that his decision to accept the mission was probably related to his relationship with Lena. She replays a particular scene from the past in her head several times, unable to take back her own disloyalty or perhaps even to understand it. It also becomes clear that the distortions of Area X are psychological as well as biological: the monsters that roam the earth run parallel to the beasts that Lena glimpses in the corners of her own mind. She and her cohort cling to their roles as observers, even as the barrier between them and the untamable nature they traverse proves to be illusory. In one of the decade’s most spectacularly overwhelming sensory experiences, Annihilation‘s conclusion dramatizes these dual senses of alienation from yourself and connection with your landscape, playing out like a thunderous DMT-assisted update on 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Garland adapted Annihilation from Jeff VanderMeer’s novel of the same name, but the film resembles the book only in mostly superficial ways. At a time when unimaginative and crassly commercial takes on existing franchises dominate the movie industry, Garland deserves recognition for using an adaptation to pursue an idiosyncratic original vision, rather than simply cashing in on preexisting fans. (Sadly, his audaciousness probably contributed to Paramount’s apparent disinterest in the film and its subsequent failure at the box office.) Annihilation is an audiovisual marvel and a feat of genre storytelling, one that finds meaningful resonances with contemporary life despite its outlandish premise. To live in the 2010s was to experience regular fragmentations of one’s own consciousness: attention dispersed across multiple locations at once, seemingly incompatible identities dissolving into one another. Historical egocentrism tempts us to chalk this feeling up to the effects of the internet, and that’s surely a contributing factor. But Annihilation reminds us that these fragmentations are as deep and primal as our very cells, as old and terrible as awareness itself. —ANDY CUSH

Read our 2018 essay “Annihilation Deserves Much Better Than the Raw Deal It Got From Paramount” here.

Burning (2018)

The Korean New Wave movement emerged from a country destabilized by economic insecurity and social stratification. In the wake of the Asian financial crisis of the late ‘90s, filmmakers like Park Chan-Wook, Bong Joon-Ho, and Lee Chang-dong responded to a changing cultural landscape with films that dealt explicitly with these tenuous conditions. IMF bailout packages and crumbling generational business models inspired movies about betrayal, memory, masculinity, and the long shadow cast by Western interventionism. Think of The Host‘s explicitly American antagonist, or Oldboy, which has as much to do with class relations as with kidnapping and hypnotism. Lee Chang-dong’s 1999 film Peppermint Candy was an unflinching portrait of corruption and crisis, told backwards, tied up in the story of a single man across a single lifetime. It dealt with brokenness—cultural, personal, and economic—and with weak, pitiless men.

The South Korean economy changed significantly between Peppermint Candy and Lee’s 2018 film Burning. Korean millennials, like American millennials, were fucked over by their parents’generation; class divisions are starker than ever, and prosperity isn’t promised. “The millennials living in Korea today will be the first generation that are worse off than their parents’generation,” said Lee in an interview with Variety. “They feel that the future will not change significantly. Not able to find the object to direct their rage at, they feel a sense of debilitation.”

Essentially a thriller about credit card debt, Burning is very much in the tradition of the Korean New Wave, tackling the personal as a function of the economic. But its approach is singular, and uniquely global. Our protagonist is Lee Jong-su, an aspiring novelist living near the North Korean border, who finds work where he can. He winds up in a strange kind of love triangle with his one-time neighbor Hae-mi and a slick, globe-trotting rich kid named Ben (Steven Yeun, never better.) Ben’s “fun”-oriented lifestyle, his Porsche, and his Gangnam apartment signal his inherited wealth, and, over the film’s two-and-a-half hour runtime, contribute to mounting tensions between the characters. The possibility that a murder has been committed exacerbates the situation, and the slow smolder of cultural division becomes a literal conflagration. Rendered digitally in rich blues and violent golden-hour oranges, Burning is a primal scream on behalf of a generation, and one of the decade’s most compelling depictions of the millennial situation. —WILL GOTTSEGEN

High Life (2019)

Great sci-fi tends to have an aesthetic responsibility. The images in 2001: A Space Odyssey are cold and measured, presenting space as medium for evolution, rather than its endpoint; the sepulchral dinginess of Blade Runner works in parallel with its questions about identity, technology, and the ambiguities of memory; in Solaris, psychological instability is mapped onto the rippling green of a hostile ocean. These high-minded epics use their own visual grammar to approach the limits of human experience, and to conjecture about what comes next, suggesting that what a new historical age might look like is as important as anything else.

Claire Denis’vision of the future is organic, physical, and overwhelmingly orange. High Life tracks a group of death row prisoners from earth to space, where they’re ostensibly given a second chance, hurtling towards a black hole in the hopes of collecting valuable data from the outer reaches of the universe. The ship is both prison and laboratory, with Juliette Binoche as a sort of witch doctor using the crew for experiments in human reproduction (one character calls her a “shaman of sperm”). Visually and thematically, Denis is more concerned with bodies than with environments. She coaxes primal, animalistic performances from her cast, lingering on sweat, saliva, blood, shit, and semen. We see people eat, sleep, and fuck. There’s even a recurring shot of the ship’s mechanism for separating human byproducts into grey, white, and black water.

Space isn’t supposed to look like this. The future isn’t supposed to look like this. Denis posits that for all our technological progress, and our dreams of a sterile, asexual future, there are certain physical realities we’ll never escape. The prisoners describe the sensation of near-light speed travel as that of “moving backwards even though we’re moving forwards, getting further from what’s getting nearer.” The deviant aesthetics of High Life seem to mirror that sentiment, foregrounding human limitations over fantasies of the stars. — WILL GOTTSEGEN

Read our April essay “Claire Denis’s Harrowing High Life Is a Sci-Fi Movie About Prison, Not Space” here.

All images screenshots except: The Social Network (Columbia/Kobal/Shutterstock); Bridesmaids (Suzanne Hanover/Universal/Kobal/Shutterstock); Frances Ha (Pine District/Kobal/Shutterstock); Mad Max Fury Road (Moviestore/Shutterstock); OJ: Made In America (M. Osterreicher / Courtesy of ESPN Films); Minding The Gap (Hulu / Courtesy Everett Collection)