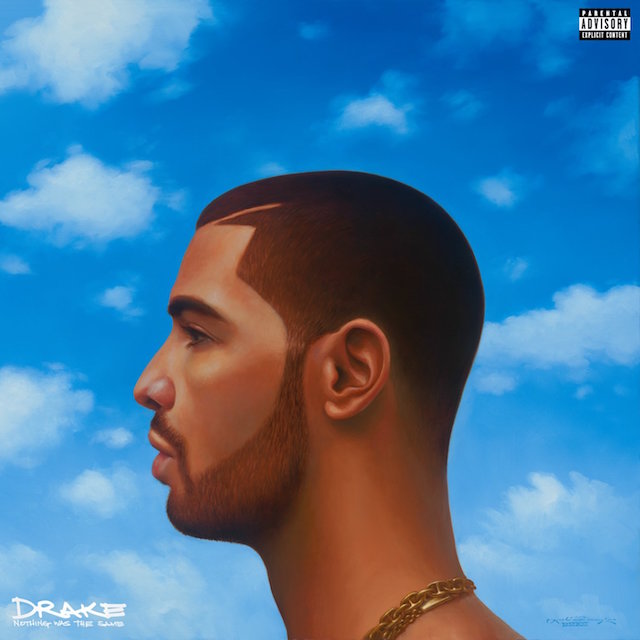

Release Date: September 24, 2013

Label: OVO/Young Money/Cash Money/Republic

Before YOLO was something your mom texted you ironically, Y.O.L.O. (You Only Live Once) was the name of a planned mixtape between Drake and Rick Ross. The two have a history of memorable collaborations, but their connection as avatars of contemporary rap will prove to be much more lasting. Since around the turn of the millennium, rap has been wrestling with the definition and importance of “realness” — thanks mainly to Kanye West, but also because of Andre 3000’s shapeshifting and Cam’ron’s pink furs and 50 Cent’s gunshot wounds. Kanye won out on the strength of sheer genius, eventually leaving two diametrically opposed rappers — one a half-Jewish Canadian ex-child actor, the other a one-time football player from Miami’s Carol City projects turned corrections officer — to fight out the death rattle of a debate neither wanted to be at the center of in the first place.

You know this now, of course, but Drake and Rick Ross are victors, both likely helping to alter how rap will operate years down the road. Rozay triumphed by creating a world in which the concept of “real” didn’t exist at all. He was outed as an ex-cop then immediately wrote his most important song by comparing himself to America’s most legendary drug dealers. He consumed hate like Kirby and it only made him more powerful. But what Drake did is more enduring: He changed the definition of “real” entirely. For him, at least, the concept of realness didn’t refer to childhood realities or street bona fides (though he still sometimes panders to both), but to total emotional openness. He fully came into his own on 2011’s “Marvin’s Room,” an R&B song where he mutters to himself for six minutes about drunk dialing an ex. It started as a one-off track leaked onto the web, but quickly became an organic radio smash, with the newest megastar of popular music’s most unforgiving genre softly singing, “The woman that I would try / Is happy with a good guy / But I’ve been drinking so much / That I’m-a call her anyway.” This was nothing less than a redefinition of manhood.

Drake won the little battles — like Common calling him soft — and he won the war. With two straight Top 10 singles, he is now bigger than ever. It doesn’t matter that a Google search for “Drake” + “simp” returns 3.16 million results. It doesn’t matter that Bossip posted a new track called “Girls Love Beyonce” under the headline “Simp or Dopeness?” or even that he named a new song “Girls Love Beyonce.” Drake knows all of this, and it has hardened and emboldened him. How could it not have? How could he not come back more confident, more defiant? How could he not follow through on the prediction — “my junior and senior will only get meaner” — that ended his sophomore album Take Care? This is the lens through which to view his third album Nothing Was the Same, a steely affair that finds Drake and longtime producer Noah “40” Shebib pulling their sound and worldview further inward to increasingly murky results.

Also Read

KEEPING IT REAL — ROUND TWO!

Drake’s confidence — in his talent, in his vision — is understandable, if not admirable. But there is a downside to the shedding of humility, as well as the fear that accompanies it, and it’s what bogs down an album that was shaping up to be his best. With Nothing Was the Same, Drake and 40 invest too much in their own hype, in the praise that crowned them as sonic innovators and Drizzy as a rapper who could be both a simp and a player. Compared to its sprawling, dynamic predecessor, this album too often regurgitates 40’s iced-over soundscape to the point of dreariness, while Drake — perhaps unsurprisingly — reveals that the redrawn parameters of masculinity allow for plenty of space to be a plain old bro.

Having strength in one’s convictions can be freeing, and the run-up to Nothing Was the Same is a case in point. Drake establishing himself as an unmovable force was the only way he could pull off “Started from the Bottom,” a sneering yet wholly ridiculous darkening of his pop smash “The Motto” that is nonetheless one of his best singles. It was the only way he could get away with “Hold On, We’re Going Home,” a delectable shred of new-wave cotton candy that features Drizzy and guest Majid Jordan singing only in their high registers. How else could he release a song called “Wu-Tang Forever” about sexual power dynamics? These are confrontational songs, all three of them. Each is not without risk, but they drip with self-assurance and taunt like a wide receiver who knows he can beat his man at will. This is Drake at his best, when his innate pop skills combine with a mischievous desire to see exactly what he can get away with.

But such convictions can lead one into rocky territory. The aforementioned tracks suggest that Drake and 40 are far from boxed-in by their own sonic palette, so maybe this album’s grey, amelodic streak is the result of the duo getting drunk on self-mythology. Their sound, minimalist and misty, is derived from the atmosphere of ’90s R&B, the slow-mo seep of DJ Screw and the moping thump of Kanye’s 808s & Heartbreak, and in cracking open that matrix, they altered the sound of the radio and let loose a stream of imitators/collaborators (like the Weeknd and Jhené Aiko, who appears here). But never has that template sounded more hollowed-out than it does on Nothing Was the Same, which flips back and forth from basic Just Blaze rips to keyboard pulses frozen in amber. What separates this album’s “Furthest Thing” or “Connect” from staples off Drake’s 2009 mixtape So Far Gone? Nothing really except that the former two sound like someone was squeegeeing a floor in the studio. The frosted atmospherics of “Own It” and “The Language” are similarly reductive — this is what it sounds like when a Drake album takes many steps backwards.

Far from all are duds, mind you: “305 to My City” is a stripper anthem submerged in the waters of Biscayne Bay, and the simultaneous thrashing of tortured yelps, garbled commands, and piped-in backing vocals at least adds depth to an album whose production is startlingly surface level. Boi-1da’s “Pound Cake” brilliantly slices Ellie Goulding’s coos, while “From Time” and bonus track “Come Thru” are bouncy and melodic, the feeling of air being let into an overly stuffy room. But Take Care now looks in retrospect like a kaleidoscope, with its YouTube sample of Aaliyah confidant Static Major and Stevie Wonder harmonica solo and flip of New Jack Swing and dollop of house music. Nothing Was the Same didn’t need to build off its predecessor, but is it a coincidence that one of the absolute standouts (the Sampha-assisted “Too Much”) calls back directly to the stunning final stretch of Take Care?

On Take Care, Drake allowed the Weeknd to flesh out his sinister side, but there was also an undercurrent of tenderness on tracks like the title track or “Look What You’ve Done.” He was also bright and clear on origin stories like “Over My Dead Body” and “The Ride,” displaying a genuine, relatable self-awareness that differed from his normal self-awareness, which was actually just him acknowledging that he’s an unforgivable asshole to women in his life. Even if you didn’t see yourself in Drake — didn’t see your relationships in his — he still offered a way to connect to his music.

Here, those openings are harder to find. There is “Own It,” in which he elevates a girl in his life to his level (though we do know where this typically leads). There is “Started From the Bottom,” gritty and inspiringly mean. There is the open therapy session “Too Much” and bits of the opener “Tuscan Leather,” in which he lays out interpersonal problems but comes off as a measured mediator. There is the earned swagger of “Pound Cake / Paris Morton Music 2.” But overall Nothing Was the Same is cold and isolated, and it’s not hard to understand why.

“I’ve made a lot of music about love being the only thing I’m missing. I think this is the first album I’ve made saying, ‘I’m okay. I’m enjoying right now,'” Drake told GQ writer Michael Paterniti in June. “Maybe this is my time to grind it out, make a run for it and add some memories with my boys.” If that sounds like a frat boy talking, it’s because Drake brags across Nothing Was the Same about being isolated in his mansion recording his album, a place his “boys” call Disneyland. He’s spent a lot of time in a very expensive frathouse of his own design, playing tennis and romanticizing his own bad behavior. No new friends, after all.

This is mostly a subtle shift for Drake, the defiance he derived from his version of realness now consuming the other aspects of his personality. The weird thing, though, is that it feels put on, like a puffed-out chest that at some point will have to recede. Drake acknowledges too that he’s trying to be someone he’s not: “All these ’90s fantasies on my mind,” he spits during the third verse of “Tuscan Leather,” referring to the aesthetic that has almost come to dominate his 2013, right down to the instant meme that was his ridiculous Dada two-piece and Tims. The man who redefined “real” now finds himself drawn to the imagined.