“That’s the dog. That’s the dog.”

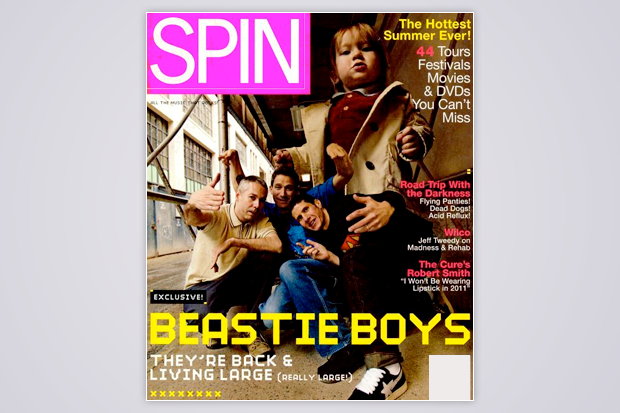

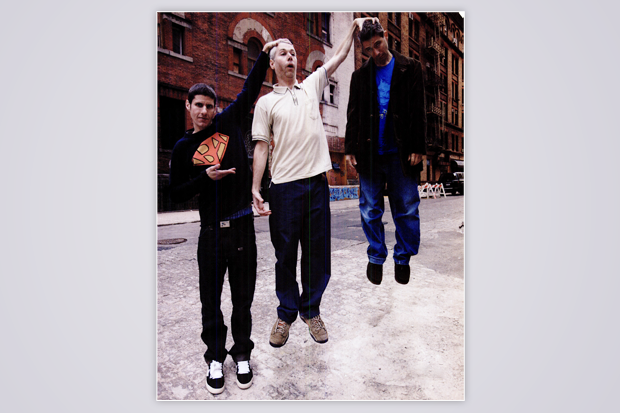

Adam “King Ad-Rock” Horovitz, Adam “MCA” Yauch, and Michael “Mike D” Diamond are in the back of a Lincoln Navigator, and we’re all driving toward a loft on Manhattan’s Lower East Side where the Beastie Boys used to play music while battling blood-hungry rats and unscrupulous landlords. We’ll arrive at the loft in ten minutes. But right now, there’s a terrier crossing the street, led by an old man wearing a cowboy hat. “This is a great story,” Yauch says, looking at Horovitz. “Tell the story about the dog.”

“This fucking little piece of shit dog bit me twice,” says Horovitz. The others don’t laugh, but not because the statement isn’t funny — they don’t laugh because these guys always seem to communicate through one-liners. In Beastie World, this is conventional dialogue. Diamond sardonically voices fear that such a statement will make the Beastie Boys seem like animal haters, but Horovitz is unmoved. “I don’t hate animals,” he says. “I hate that dog. And that dude with the cowboy hat? That’s my neighbor. I went over to his house when I first moved in, and I rang his doorbell to introduce myself. But there’s no answer. I wait and I buzz again. This time I hear the dog inside barking and barking. The guy finally comes to the door, and he’s 80 years old, and he’s completely naked, except for his underwear. He opens the door six inches, and I say, ‘Hi, my name is Adam,’ and he says, ‘Don’t let the dog out’ So I bend over and block the door with my hand, and the dog bites my finger and will not let go. I finally push the dog away, but now blood is everywhere. It’s all over my shirt. And the guy says, T can’t talk now, I’m in my shorts.’ He closes the door on me. He never said a single word about the dog!”

This is only the first half of the story, the second half details another incident a year later involving the same terrier diving into Horovitz’s calves with extreme prejudice. Diamond questions the accuracy of the story, pointing to Horovitz’s inability to describe the old man’s underwear. Yauch suspects that Horovitz just visited the neighbor so that he could later ask to use the man’s swimming pool. The conversation feels like something from what MTV would have classified as a “rockumentary” in 1989. It’s clever, rapid, and a bit vapid.

We’re driving around New York because more than anything, the city defines who the Beastie Boys are. We’re touring the places they loved before anyone loved them, and the trio is at the apex of their comfort: operating as an insular group, obscurely referencing one another’s obscure references, bantering about the quality of pedestrians’ mustaches, and making a living off their sharp, city-bred wits. When all three Beasties are in the same place at the same time, it’s impossible to get a straight answer about anything.

And it’s not much easier when they’re alone.

For nearly 20 years, the Beastie Boys have represented all things to all people; they just haven’t done so at any one time. On 1986’s Licensed to Ill, they were downtown wiseass punks pretending to be suburban imbeciles; they toured with Madonna, dated Molly Ringwald, and embraced black culture so aggressively that they almost seemed to ridicule it. By 1989’s Paul’s Boutique, they had evolved into musically protean West Coast stoners with an affinity for billy goats and Japanese baseball legends (Sadaharu Oh). Check Your Head, proved they could play their own instruments and became 1992’s college-rock prototype for knit-hat slackers. Ill Communication showed how rap rock should be done with “Sabotage” and became the soundtrack for ’94 Lollapalooza ticket holders who wanted to reminisce about episodes of Starsky & Hutch they’d never actually seen. Hello Nasty was for Buddhist-loving electro ironists interested in Boggle and insane reggae legends (Lee Perry). And through it all, the Beasties have always been a step ahead of the cultural curve.

Few groups have changed their ideological existence as much as the Beastie Boys. For more than 40 years, the Rolling Stones have expressed the same general sentiments that they did in 1964; AC/DC has been around for 31 years, and they’re still expressing the exact same sentiments that they did in the summer of ’74. Ideologically, the Beastie Boys have almost nothing in common with who they used to be. If the ’86 B-Boys and the ’04 B-Boys met each other now, somebody would end up in the emergency room — or at least covered in egg yolks. Yet one thing has remained unchanged over the years, and it’s the unifying principle that has allowed Horovitz, Yauch, and Diamond to remain relevant longer than anyone could have anticipated: The Beastie Boys understand what it means to be cool. It’s almost as if being cool is their full-time job. They can make any retro reference seem contemporary; they innately sense the line between savvy cultural recognition and esoteric self-indulgence. They basically discovered Spike Jonze, made shouting out neglected soul-jazz musicians trendy (Dick Hyman, Eddie Harris, Richard “Groove” Holmes), and taught people born in 1978 to care about the American Basketball Association. The Beastie Boys are hip-hop’s version of the “mavens” that Malcolm Gladwell wrote about in The Tipping Point: They are cool hunters for the rest of us.

But during the six years since their last album, it’s become clear that the Beastie Boys have become less invested in the process of manufacturing cool. They closed their magazine and record label Grand Royal in 2001, then officially declared bankruptcy in 2002, even holding an online auction to sell the label atbid4assets.com. They’ve made social responsibility an increasingly important part of their identity: The group has chastised fans they felt were being abusive toward women in mosh pits; in 1999, Horovitz publicly apologized for the group’s homophobic lyrics circa Licensed to Ill; Yauch remains an earnest celebrity front-man for the movement to liberate Tibet; and last year, they posted to their website the antiwar song “In a World Gone Mad,” which was mocked for its simplistic (if well-meaning) message.