One day in the third-grade lunch room I somehow discovered I was capable of singing “Tutti Frutti” with all new words—clear, intelligent and rhyming ones—for what I was later told was minutes without stopping.

Why Little Richard set me off, I’ll never know, but I do know it caused enough of a scene to lure lunch ladies out from the kitchen, in aprons, who peeled off their rubber gloves and hairnets and watched. God knows what I must have looked like. I remember not quite understanding what was happening, where all of the words were coming from, only that when I really got going, I could almost watch myself doing it.

I do remember it was Fiestada day. All month we waited for Fiestada, an octagon-shaped Mexican sausage pizza our suburban elementary served every third Friday for cultural flare, instead of the standard grilled American cheese. They felt like holidays, Fiestada days; I guess we were just that Pennsylvanian.

It was a fall Friday, 1987, with a varsity football game that night where we could wander the grounds in groups eating Mike & Ike’s and begin to stare at girls, unabated by our parents in the bleachers. In just a few hours we’d feel like what we thought young adults felt like, and a tangible anticipation had arisen in the lunchroom. The magic of the moment was thick.

I remember the actual eating was over and most of the trays had been cleared, but Ms. Norma, the head lunch lady, hadn’t dismissed us just yet. It was always this time of day, cooped up full of processed food and sugar-juice, aching for the playground doors to whip open, that our school’s collective kid-energy always reached a buzzing, frenetic peak. When the lunchroom air grew this combustible, my friends and I had taken to randomly pounding on tables and singing out loud like stimulated chimps, and on a fall Fiestada Friday, the primal urge to flex would not be suppressed.

Without warning, my neighbor Brian jumped up and wailed “Welcome to the Jungle”, while a dozen of us howled and smacked the tables. He forgot the last part of the second verse, so my guy Adam belted AC/DC’s “Thunderstruck” and we closed-fist beat the tables. Around the fourth “Thunnn-durr!” Adam belched, lost his wind, and I spotted my opportunity. Standing on my seat I launched right into “Tutti Frutti”—stop, I know, horribly out of place, but—pause that scene—I did have a plan.

Our music teacher had played “Tutti Frutti” the day before, and while singing it in the shower that night, who knows why, I tried my own words, and soon found new rhyming lyrics pouring out faster than I could think them — so fast they almost didn’t feel like my own. It was oddly effortless, and as I caught a wave and slid into a sort of fugue state it struck me: I had stumbled across a massive social currency, like the kid on the playground who can pop his shoulder out of joint at weird angles.

I had planned to do it (…what was it?) for just our table, but between the dual fail of table king Brian busting an Axl and throne attendant Adam blowing a fuse, I opted for a full-on coolness coup and stood on my chair. With one brash display of verbal acuity, I could drop a few jaws, climb a few table rungs—maybe nab an uneaten Fiestada—maybe steal a glance from Kristy and Megan at the table to the right, whom I would then tell “Maybe I’ll see you at the game tonight”, and walk off.

So, 8-year-old-me did it, an extended, improv proto-rap to a Little Richard melody. The first few lines were rough, then—BLAOW—spontaneous combustion, my effort inverted and what I’d been trying to do was happening on its own. Out came sly lyrics about Sega Genesis, the WWF, Poison, Cindy Crawford, Bo Jackson, and the Philadelphia Eagles, even lyrics about my friends and the things around us (though I wouldn’t say I was completely cognizant). It all felt strangely familiar, like an ability I must’ve forgotten I had.

At some point in the show, our resident bully Rhett (who spat on my back that morning’s recess and is now a mattress salesman in rural Georgia), leaned in from behind and shrilled his highest, most-vilest “Sweet Child O’ Mine”, right in my ear. I was way too deep in the zone to react, but what was happening inside me knew just what needed done. As I turned, the “Tutti-Frutti” melody went monotone sing-song and I began to dissect his entire appearance and personality in ruthless swipes of analytical rhyming.

I compared his singing to cats copulating, I pointed out his watermelon-sized and egg-shaped head, I negged his rusty-ass Schwinn bike (which I also admitted to having blown the seat off of with M-80s.) I reminded him about that time in 2nd grade he came back from the bathroom with poo on his leg, and about the week before last when he cried after Adam clotheslined him during recess, and for the deathblow, I inquired why his mom’s legs didn’t change shape from her thighs down to her ankles — the lunchroom exploded, and someone hit Rhett with a strawberry milk.

No sooner had I defeated the dragon than the bell rang, lunch lady Ms. Norma propped the playground doors, and 70-some kids sprinted out into autumn. As Rhett slunk off to the bathroom, and I stood there in shock, Kristy and Megan approached with two uneaten Fiestadas—dry as plywood, but you can’t eat gold either—and told me they’d see me at the game. As the girls left, Ms. Norma returned with a warm octagon wrapped in aluminum foil, leaned her corpulent, heavy-smoker face in, winked, and said “You just keep doing what you do.”

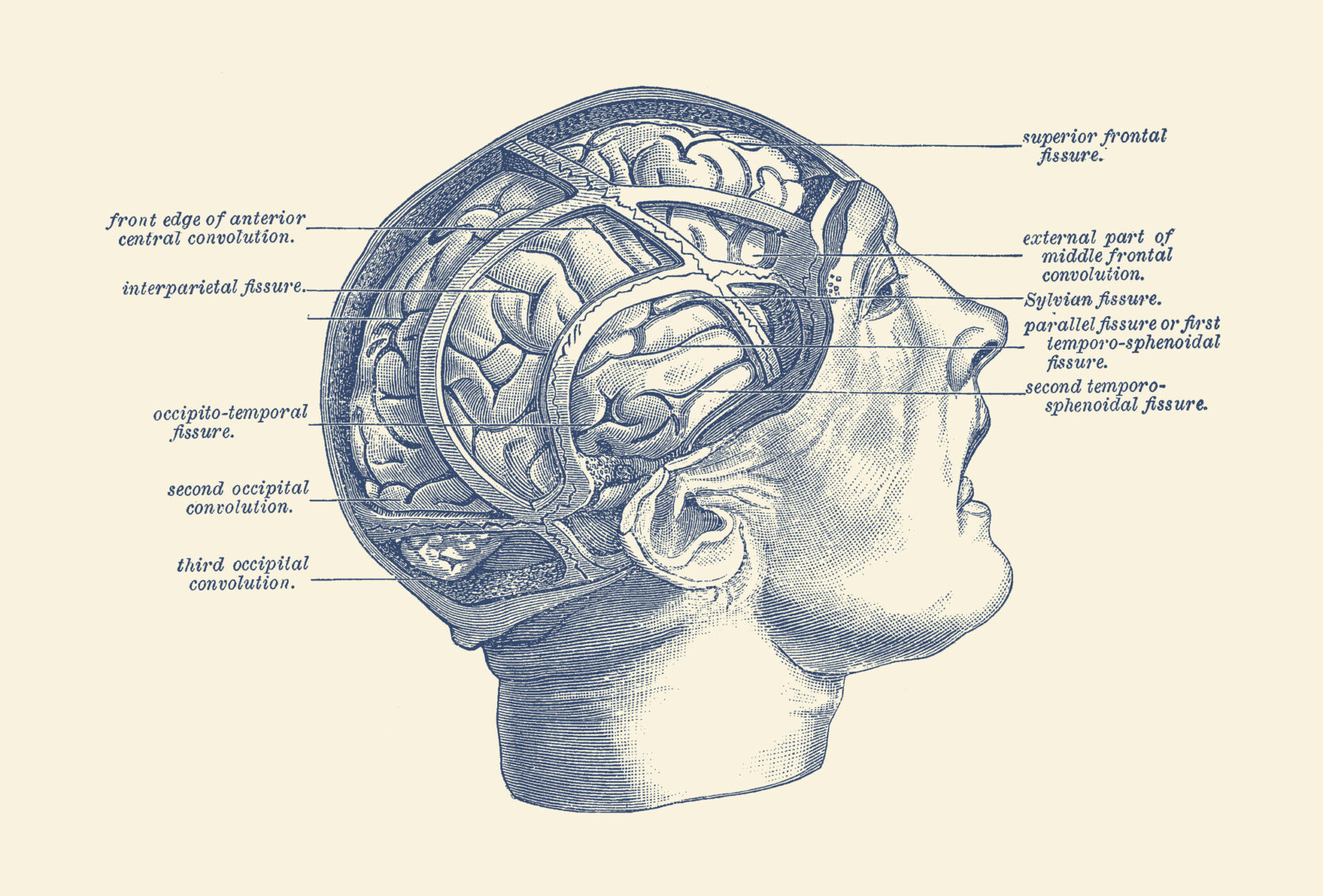

But what was I even doing? It wasn’t until the Beastie Boys debut reached town in ‘88 that I even realized I had been rapping, let alone freestyling. Well, leave it to the masters of modern science to explain the living daylights out that day’s supernatural performance, identifying every last detail of the action in my gray matter down to the exact neural networks firing throughout my tempest. It was a bummer to learn I’m not a deity, but the finds are pretty fascinating nonetheless.

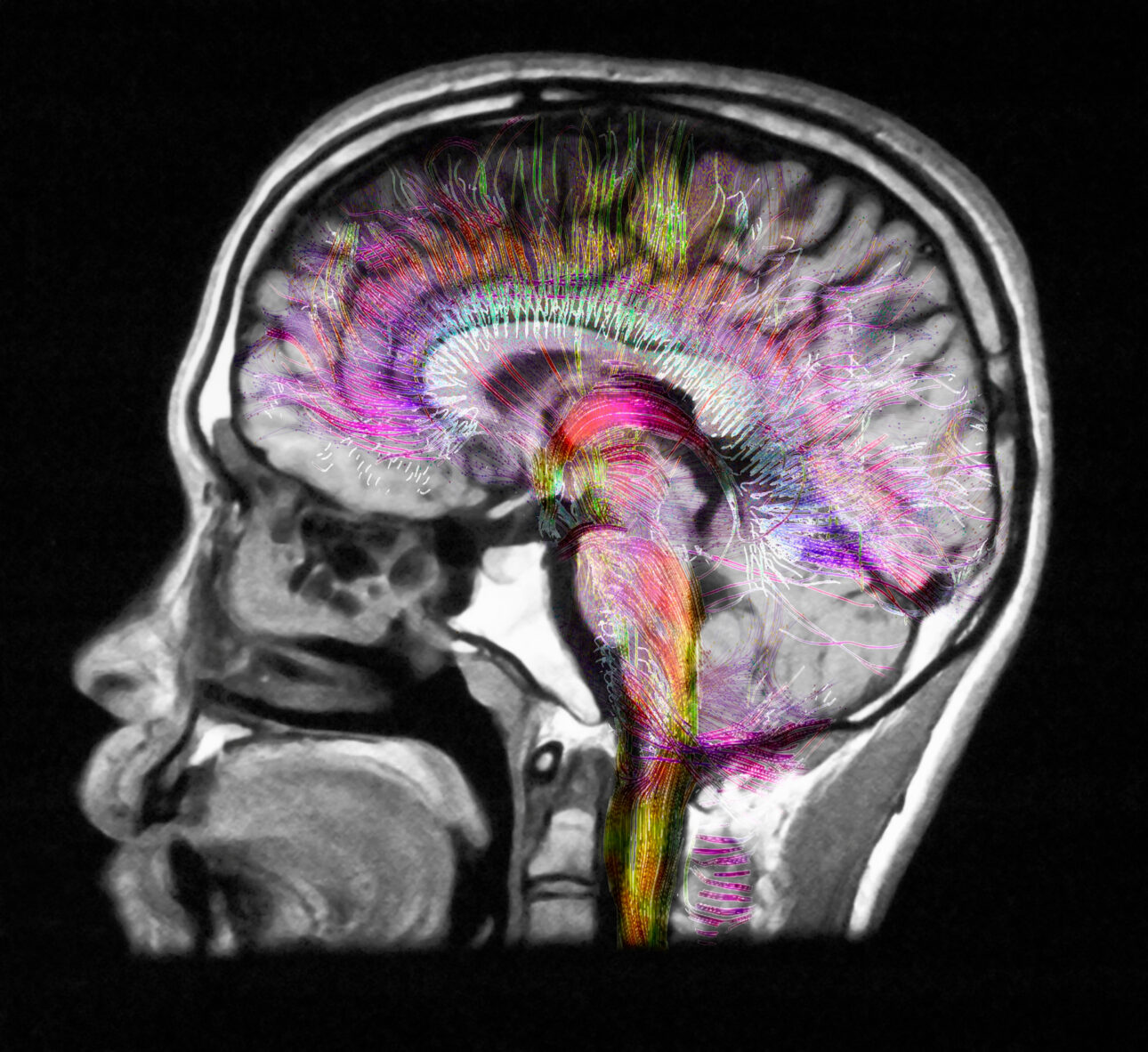

Dr. Siyuan Liu of the National Institutes of Health is the one who pruned my angel wings, when in 2012, he then gathered 12 talented MCs and monitored each with an fMRI machine while they rhymed. Over the same 8-bar instrumental, each rapper first freestyled, then performed pre-written verses, and lo and behold, during the freestyles, certain brain regions not typically known to interact were observed working in tandem. (Fun fact: Dr. Liu performed a similar study with jazz musicians, and the same areas lit up during their improv.)

In med-speak, an upswing of activity in the medial prefrontal cortex was observed during freestyles (an area involved in motivating thoughts and actions), with a simultaneous decrease of activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal zone (which self-monitors and supervises our thoughts). NIH study co-author Dr. Allen Braun describes this as the perfect equation for open-gate creativity, enabled by an “absence of attention”. The doctor elaborates, “When the attention system is partially offline, you can just let things fly […] without critiquing, monitoring or judging them.”

In layman’s terms, this means that during an actual freestyle the conscious-and-critical mind state with which you read and digest this sentence ceases to exist. No chatty inner voice, no “hmm, on second thought”, and as a result, no timid performances thanks to self-doubt. While in the freestyle state, the mouth displays the mind almost instantly, and thoughts are manifested as words without first passing through the mental filters of standard consciousness — pure creative freedom.

So that’s what happens — but how does it happen? Many freestylers don’t even appear to be trying to rap, but instead, tuning into some cosmic frequency and broadcasting rhymes like a radio. From where does this eternal transmission originate? Is it an internal or external source? Modern science has again uncovered answers, as further freestyle research studies in academia’s most hallowed halls have identified a Voltron-like brain mode called FBS.

In 2017, Cambridge University research psychiatrist Dr. Akeem Sule and neuroscientist Dr. Becky Inkster performed additional analysis on the findings of Dr. Liu and the NIH, seeking to reveal how freestyle rappers are able “enter and stay into an altered state of mind […] that can cause disassociation with time, place, space, and even self.” The answer is what could reasonably be called a neurocognitive preset, which the duo identifies as FLOW Brain State (FBS).

FBS stimulates five key areas in the brain that otherwise rarely work together; areas that control functions regarding emotion, motivation, mental processing, language and motor skills. It’s quite the unlikely cerebral collab, and when FBS really gets cranking, it seems a semi-transcendent state becomes reachable, an ethereal place any freestyler worth their spit at least knows the name of, and seeks to reach at least once: the Zone.

The Zone is a mysterious dimension of creative cruise control — without self-realization or linear thought. Accessing it isn’t easy, and many never will, though one universal rule of thumb exists: searching instead of receiving will never lead to The Zone. Trying too hard is what inevitably keeps any MC from reaching this dopest and deepest level of flow, the purest state—and by strictest definition, the only state—of freestyle.

While in the Zone, a defocusing of the ego occurs, thought and verbalization merge, and the rapper becomes present but not: manifesting rhymes rather than trying to make them up. When the Zone experience reaches its apex, a creativity so immediate and involuntary takes hold that a depersonalization occurs wherein many rappers have reported the sensation of their words not feeling like their own—it’s what Eminem means by “Lose Yourself”.

Today however, I stand prepared to attest to an even deeper level of freestyle, to be known as Third-Eye, in which semi-consciousness returns and an independent line of thought becomes available to the MC, while Zone-rhyming continues unimpeded. This means of thought allows for lucid idea-browsing, as well as basic observation of one’s surroundings. Third-Eye also brings a slowed conception of time, but with no reduction in speed-of-thought, and as a result, scores of words always remain ready well before the MC’s mouth is.

Third-Eye freestyling is no minor matter. It’s the revelation of a built-in brain hack, that is, dare we say … near-Holy? After all, channeling voices in a state of partial possession is routine stuff throughout the Bible, as well as in revivalist and Baptist church traditions, where enraptured parishioners have long been known to shout and sing at length in unidentifiable dialects (Check out Acts, 2:4, as the Spirit makes Jesus’ disciples speak in tongues and chant rhythmically, a real cypher if ever there was one.)

Of Godly origin or not, freestyle was once a sanctified thing, a happening not to be faked, and a title too special to be slapped on any written and recorded verse. In mid-Atlantic urban regions during the ‘90s, I routinely witnessed MCs harassed verbally, refused stage time at open mics and muted by soundmen for false freestyling. I once saw a deceitful MC stripped of his shoes and pants for fronting about rhyming “off-the-top”. My rap colleagues in Los Angeles have concurred; in the golden-era ’90s, fake freestyle was a “stolen valor,” like civilians falsely claiming military service.

All this pomposity, yet it’s come to be known many ’70s hip-hop OGs actually looked down on freestyling as a show of unpreparedness. Other rap pioneers like Big Daddy Kane and Kool Moe Dee shun our operative definition entirely. Kane calls freestyling any rhyme about “no particular subject…basically just bragging about yourself”, adding, “Off-the-top-of-the head, we just called that ‘off the dome’.” Aww, shucks Big Daddy, our mistake. Alright, great ending, right? Now back to that third-grade Fiestada Friday varsity football victory tour.

At that night’s game, I was a golden god. Rhett had done us all dirty at least once, and my public shaming of him earned me a candy homage that lasted throughout the first half. Blow Pops, Fun-Dip, Big League Chew — Mike & Ike’s from Kristy and Megan. Twix from kids in other grades saying “Do that thing you do!”, which I would, for a bit, then drop their candy in the front-fold pocket of my Starter coat. As I watched it develop a nice bulge, I recall first grasping the true power of the spoken word … then gorging artificial sweets until my teeth hurt.

Post-graduation, The Zone and I embarked on a decade-long rap career, including battle tours with The Source and major label releases featuring collabs with multiple Grammy-winners. 30-some years later, my freestyle game is still firmly intact. So don’t you go and get funny in the comment section!

EXERCISES FOR THE FREESTYLE-CURIOUS

Whether experienced or first-time rapper, singing simple sound patterns in the shower is the perfect way to establish vocal rhythms from which rhymes can emerge — the hot water and warm acoustics also help to loosen your vocal chords and nerves.

Chant some sounds of your choice at your own pace, inserting a word here and there. Continue to add and randomly vary them, without stopping, for what feels like a minute. Take time with the words if you must, just don’t stop chanting. Even near-nonsense words can help you explore creative vocal expression.

Or, maybe try when you’re not ass-naked and covered in foam, wondering if your partner hears you moaning. Improv can get easier when the active mind is occupied with larger tasks, so try entry-level rhyming while doing the dishes, walking the dog, folding laundry, or driving (ok, the editor says not driving).

When it’s time for a beat, select a simple, mid-tempo instrumental. Look a few feet forward and relax your vision, don’t focus on any one thing. Pay close attention to the sounds you hear, let them overwhelm your mental commentary. Nod along (make sure you do, it generates great momentum), and once sound is all that’s left in your mind, try some vocals.

It doesn’t all need to rhyme yet. Just establish a rhythm, don’t break stride, and as those who fly kites must wait on the wind, stay patient. Hear your own voice in the beat, let your raps come into focus like 3D-eye pics from the mall in the 90s, as freestyles can’t be forced, only allowed to emerge when they’re ready.