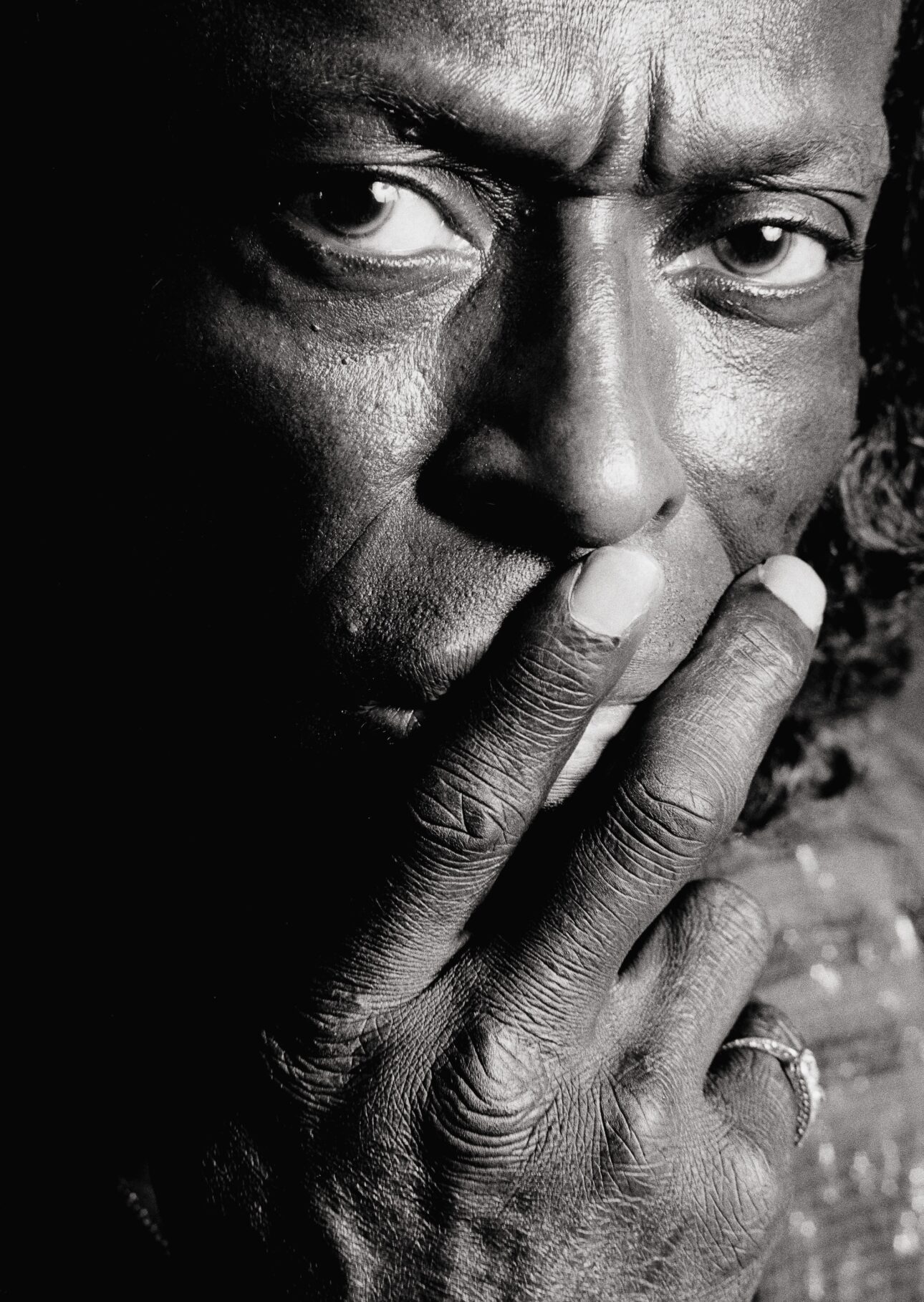

There are musicians so cosmic, so otherworldly, it seems like they came from outer space. Miles Davis is one such character – and that is what musician/visual artist Dave Chisholm depicts in his graphic novel, Miles Davis and the Search for the Sound.

The information in Chisholm’s book is drawn from Davis’ autobiography, essays and interviews. Told in first-person from Davis’ perspective, the narration is taken from his own words, giving a raw and unapologetic honesty to this visually arresting graphic novel.

Chisholm begins Davis’ story in 1987, in his doctor’s office where Davis is first given a pencil and sketchbook as a way to rehabilitate from a stroke that paralyzed his right hand. The timelines are shifting, going back to 1933 when Davis was first visited by “The Sound” during a nighttime walk. Back to 1987, a frustrated Davis scribbles and scribbles and scribbles in his sketchbook. Then in 1944, a teenaged Davis arrives in New York City to attend Julliard, but instead begins playing with Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie “Bird” Parker. The chapters are strung together with Davis’ scribbles, which would later turn into full-fledged artworks. As he says in the epilogue: “A painting is music you can see, and music is a painting you can hear.”

The details of Davis’ life unfold beautifully in Chisholm’s expressive drawings with particular attention paid to the music and the visual representation of it. Each line and shade is purposefully chosen to convey the mood, the situation, the feeling, and above all, the music. What Chisholm gets across with both words and illustrations is deeply musical, and at the same time deeply personal.

And Chisholm is just the right combination of accomplished trumpet player and visual artist to unpack Davis’ complex life. He presents the icon’s decades of music with an expert’s understanding of the trumpet, and a candid look at Davis’ personal shortcomings, including relationships and his drug abuse.

Davis’ son Erin wrote the foreword to Miles Davis and the Search for the Sound. As one of the three executors of his father’s estate, he handpicked Chisholm for this.

How did you get into telling music and musicians’ stories through graphic novels?

I’ve always made comics and I’ve always played music. I ended up going to college for music and getting three degrees, all the way to my doctorate in jazz trumpet from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY.

My first published graphic novel was a book called Instrumental. Z2 –– the publisher of the Miles book –– published it, and it also had a full-length album of music that lands somewhere between modern jazz and cinematic post-rock. The success of that led to Chasin’ the Bird: Charlie Parker in California, which directly led to the Miles book.

How?

Erin Davis read and enjoyed the Parker book and was interested in my putting together a graphic novel about his dad. The Parker book is also told with shifting styles in each chapter. But in that book, the styles are intended to reflect the point of views of each of the narrators. Since Bird gave relatively few interviews and died so tragically young, it made more sense to present this mercurial figure from a variety of points of view. I took that shifting art style and pushed it even harder in the Miles book. It’s kind of an unofficial sequel to the Parker book.

What is your connection with Miles?

The first music I ever remember hearing is Sketches of Spain with my mom and dad spinning that on the turntable when I was maybe three years old. It mystified me. Miles’ music became a heavy obsession of mine when I was in high school. It was basically the only thing I listened to for a few years, until OK Computer came out. Then it was just Miles and Mingus with that one Radiohead album tossed in for good measure. I painted a ton of pictures of Miles back then, too.

I wanted the paintings to capture some essence of his music. Since then, Miles has been a real artistic North Star for me. His courage to change on a dime, his commitment to innovation, his authenticity — it’s a constant inspiration.

How much did your trumpet playing help you convey Miles’ story?

It definitely helped keep it as authentic as possible. For example, making sure he’s playing a Martin Committee the whole time (except for a short stretch early in his career). So many music documentaries or biopics put the focus on just about everything but the music — when the music finally starts up, there’s either dialogue or talking heads happening over the top of it.

The content of the music itself becomes the essential fabric of everything. The visuals of every chapter: the line art, the colors, the panel layout and flow, the storytelling style, the textures are designed to reflect specific aspects of the music depicted within the chapter. If Miles’ playing is more spare during one period, then the art is more stark, more minimal. If his music is more detailed, heavily orchestrated, then the art is more richly detailed. When Davis’ turns towards rock and psychedelia, the art pushes heavily in that direction.

“The Sound” is the trunk of the tree that’s the narrative. Anything that’s too remotely connected to that trunk got pruned. Miles was a fantastic cultural sponge. His friendships, his romantic relationships, his bandmates’ tastes, all had profound impacts on his musical quest. The fact that I have 25 years of experience as a professional musician gave me the perspective, knowledge, and authenticity to commit to telling a story really focusing on the music itself.

Your narration is strictly drawn from primary Miles Davis sources. Was there any interpretation on your part, or only in your drawings?

The narration is definitely adapted, remixed, recombined. I pulled from a wide variety of sources. I might put one sentence from one interview adjacent to an adapted sentence from later in his autobiography, and then follow that with an adapted sentence from early in his book. His book is freewheeling in a way, so collecting and collating his thoughts and quotes into categories was a huge process. Each quote had to be adjusted so they’d flow together well without changing the meaning. The real magic happens, however, when one quote about X might be juxtaposed over Y visual –– maybe they contradict each other where Miles’ words don’t match his actions OR in some cases it might bring a sense of foreboding to an otherwise lighter visual narrative. It’s the power of comics’ unique combination of words and visuals. You can have two separate narrative threads going.

There are distinct color palettes in the book. How were you using that in your storytelling?

Each musician gets their own color. Bird’s musical color is magenta, and it gets passed to Coltrane who abstracts the shape of the sound, and then that gets passed to Hendrix, in whose hands the sound becomes electrified, noisy. Miles’ sound gets this blue-green color (inspired by the track “Blue in Green” from Kind of Blue) that only appears when he’s playing his trumpet. Miles’ sound is so reminiscent of a human voice –– deliberately so, in his own words –– so I also opted to represent his sound often as this humanoid-shaped abstracted ghostly figure.

I’ll also add that Davis himself had synesthesia [a condition where a person experiences more than one sense at a time, like hearing colors or tasting sounds]. Since the book is told from his point-of-view, I took full advantage of the possibilities.

What was the inspiration behind the two-page spread of Miles Davis and Jimi Hendrix? That would make a stunning print.

The two of them jammed together at Jimi’s apartment in NYC, and allegedly were set to record shortly after Jimi’s death. Imagine what could’ve been! That spread turned out so awesome. If I was in charge of making prints for it, it’d be a print.

What went into the creation of the two-page spread toward the end of the book that shows Miles with all the departed greats?

That quote by Miles about seeing spirits, about speaking with his departed friends, in a way it was about Miles becoming part of that pantheon. In his final months, after a lifetime of never looking back, he played a couple of concerts in which he performed older material with old colleagues. I imagined the emotion of that moment, paired with what Davis says about communing with his dead friends and I knew that image had to end the book.