In the future, some emotionless musicologist may look back at the Strokes and wonder why they were such a big deal. Why all the fuss about one canonical album, a very good sophomore record, and a handful of loosies culled from the disappointing follow-ups? The distanced reading would deny the Strokes their extramusical power—the lazy, charismatic droop of Julian Casablancas’ eyelids and thrown-together haircut, their coordinated handsomeness, their close identification with New York cool, that evergreen cultural currency. And more than the enduring righteousness of “Last Nite,” that power is why even younger music fans continue to care about the Strokes—why they can headline festivals more than a decade removed since the last album they released that people actually liked.

This reading of the Strokes isn’t particularly unique; bands are often elevated into the canon for reasons that go beyond the merit of their music. It’s interesting that we can even talk about the Strokes in this matter, because their ascent seems not so long ago. But, yes, you’re that old—bands like the Strokes have been around for long enough that they’re no longer the new upstart, focal points of a billion buzzy profiles about the new garage or the movement or whatever. They’re baked into the consciousnesses of millions of people, with more on the way. A better question for historians might be: How did that happen?

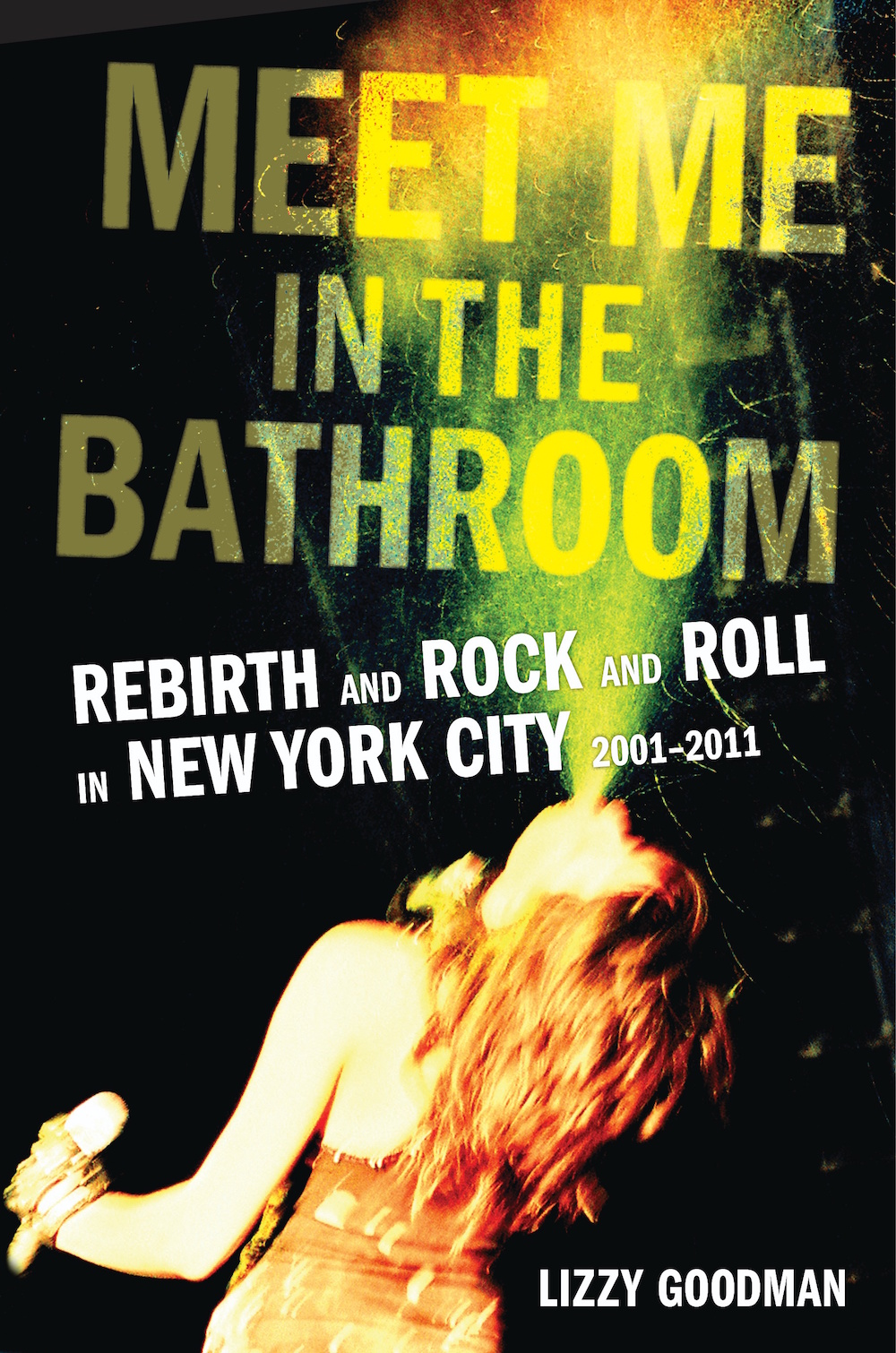

Meet Me in the Bathroom, a new oral history that chronicles the New York City rock world between 2001 and 2011, answers that question. It’s written by Lizzy Goodman, a long-time music journalist who was plugged into the scene right as it was taking off. Compiled from interviews with dozens of involved parties, including band members, managers, local celebrities, writers, industry figures and many more, Meet Me in the Bathroom digs into how these bands got so big, pairing their ascent with the revival of New York’s cultural relevance, following a long period of gestation. “We were all chasing New York City,” Goodman writes. “And for a few magical years, we caught it.”

Histories like these can be written like Simon Reynolds’ Rip It Up and Start Again or Michael Azerrad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life, meticulous studies of specific bands steeped in facts and context sorted by a somewhat detached researcher. Because of the oral history format, Meet Me in the Bathroom is much closer to Gillian McCain and Legs McNeil’s iconic Please Kill Me text, which chronicled the rise of punk rock. Instead of professorial analysis, or a healthy dose of skepticism regarding what mattered and why it did, readers get an abundance of killer anecdotes from the people who lived through it all, with any objectivity forgotten. (There are more stories about getting brutally fucked up than there are stories of meetings with label representatives, for instance.)

If you loved any of those artists—here’s a partial list: The Strokes, the White Stripes, Interpol, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Jonathan Fire*Eater, the Vines, the Hives, the Walkmen, TV on the Radio, LCD Soundsystem, the Rapture, the Moldy Peaches, Regina Spektor, the Killers—you will cherish the firsthand stories, as well as envy their existence. What could be cooler than going to one of the early DFA parties, catching a Strokes/White Stripes double bill, or going to a bar where Luke from the Rapture was serving drinks? On one level, the book reads very for us, by us—it’s recorded history for every one-time hipster who ever wanted to plant their flag in the ground and shriek with Murphy-ian conviction, “I was there!”

Apart from being thoroughly entertaining, Goodman’s book communicates the conviction of its participants that something really was happening, hype aside. “The idea of New York as a rock star was something people were very concerned with,” says critic Rob Sheffield. The city’s position as cultural hegemon had diminished by the end of the ‘90s, with Seattle the center of rock’s alternative scene. While bands like Fischerspooner and the Strokes brought some buzz at the turn of the century, the scene seemingly didn’t catalyze until September 11. One theory positioned is that the resulting turmoil paused the city’s luxury appeal, allowing people to experiment in still-cheap warehouses and apartments.

Another is that the shock of the attack destroyed any cynicism toward the new movement. “September 11 made Yeah Yeah Yeahs and the Strokes and Interpol, it made them all underdogs because they became representative of something larger,” says former RCA product manager Dave Gottlieb. Musician Jesse Malin adds: “It wasn’t like some old thing. It wasn’t some Lester Bangs thing. Or some art thing. It was young kids and hot chicks! It was decadent. You could hear these new bands in the shops when you were in the suburbs, in Urban Outfitters. It was beyond the city. It was an idea.”

The book is almost 600 pages long; I read it in three days. It’s very engrossing, though a little daunting, because it tracks a time and place that isn’t very far from us, though wholly different from the present moment. Scenes will always exist, and they will always produce great bands–the fall of a scene is where the magic flags, when bands accidentally take too much money or not enough. There was no monumental collapse for the Strokes. The band stalled once Albert Hammond Jr. got addicted to heroin, and later reunited to release a few more albums while wringing every dollar out of the festival circuit. Most of these bands continued to make and release music their fans are interested in, now with the added benefit of seeming wizened for their longevity.

The more fundamental switch is portrayed through bands like Vampire Weekend, Dirty Projectors, and Grizzly Bear, who took a more professional approach to the industry than their forebears. These bands were college-educated, and unabashed about their love of other genres, having grown up in the digital sharing era. They absolutely did not party. “There’s something a lot saner, I think, about the careerism of contemporary bands and how they want to be seen and how they want to be known for their songwriting or whatever,” says critic Andy Greenwald. “But doing that means you cannot be at the Library bar at three in the morning. You just can’t.”

That ends up being the real paradigm shift: the death of the rock star, as he lived and breathed, to be replaced by a more sober, millennial counterpart. You feel that in modern New York indie luminaries like Mitski, Girlpool, or Frankie Cosmos, who project a quieter image altogether, even when their music rocks. Consider the values of inclusion and respect that course through modern progressive culture—they won’t be found in any coke-fueled ragers in seedy East Village bars. (Another thing: The scene described in the book is very male; Karen O explicitly talks about how Yeah Yeah Yeahs were an outsider because she was a rare female singer amongst so many boys trying to party.)

Of course, New York is different now–especially for those who have lived in the city for years. Property values in Manhattan have exploded; the seedy bars are now frozen yogurt joints and chain banks. Brooklyn, meanwhile, has become overly commodified and exported to the rest of the world, who now know the musically storied, diverse boroughs by a cluster of cliched signifiers like “fixed gear bicycles” and “avocado toast.” While acknowledging the perniciousness of people who want to make culture thrive, it seems obvious that the ever-ballooning costliness of the city may one day box out even the most idealistic, dedicated progenitors. DIY venues are on the wane, and perhaps a more brutal calculus comes into play: There are now so many bands trying to make it in New York that the bar of excellence is that much higher. The Strokes put a modern slant on bands like Television and the Velvet Underground, but that’s now something everyone has done.

Certainly, prevailing trends can seem overwhelming. In the middle of the book, the late, great Marc Spitz opines about why it took so long for him to take the advice of a friend, and listen to the White Stripes record that would blow up. Eventually, it takes, but not before a few listens. “It would be easy for me to say, ‘Yeah, I was into it from the jump,’” he says. “But I was in a bad, cynical place, because it was my job to write about Mark McGrath.” The merits of Sugar Ray aside, such is the predicament of the aspiring music writer—that what’s fresh will eventually calcify and reduce to a small, dull thing far away from whatever it was that sparked the initial passion. It only takes one meaningful band to make the years of indolence wash away, and Meet Me in the Bathroom is a wonderful reminder that the next big thing can be right around the corner.