“I am the emancipator. I am the architect. I am the one that started it all.”

– Little Richard

That is quite a boast, even in the context of rock and roll (and a bit dubious, given that Ike Turner is more credibly acknowledged as the origin seed). But this documentary (streaming now) amply argues the case that before Little Richard, who died in 2020, rock and roll was fairly irrelevant on the cultural landscape.

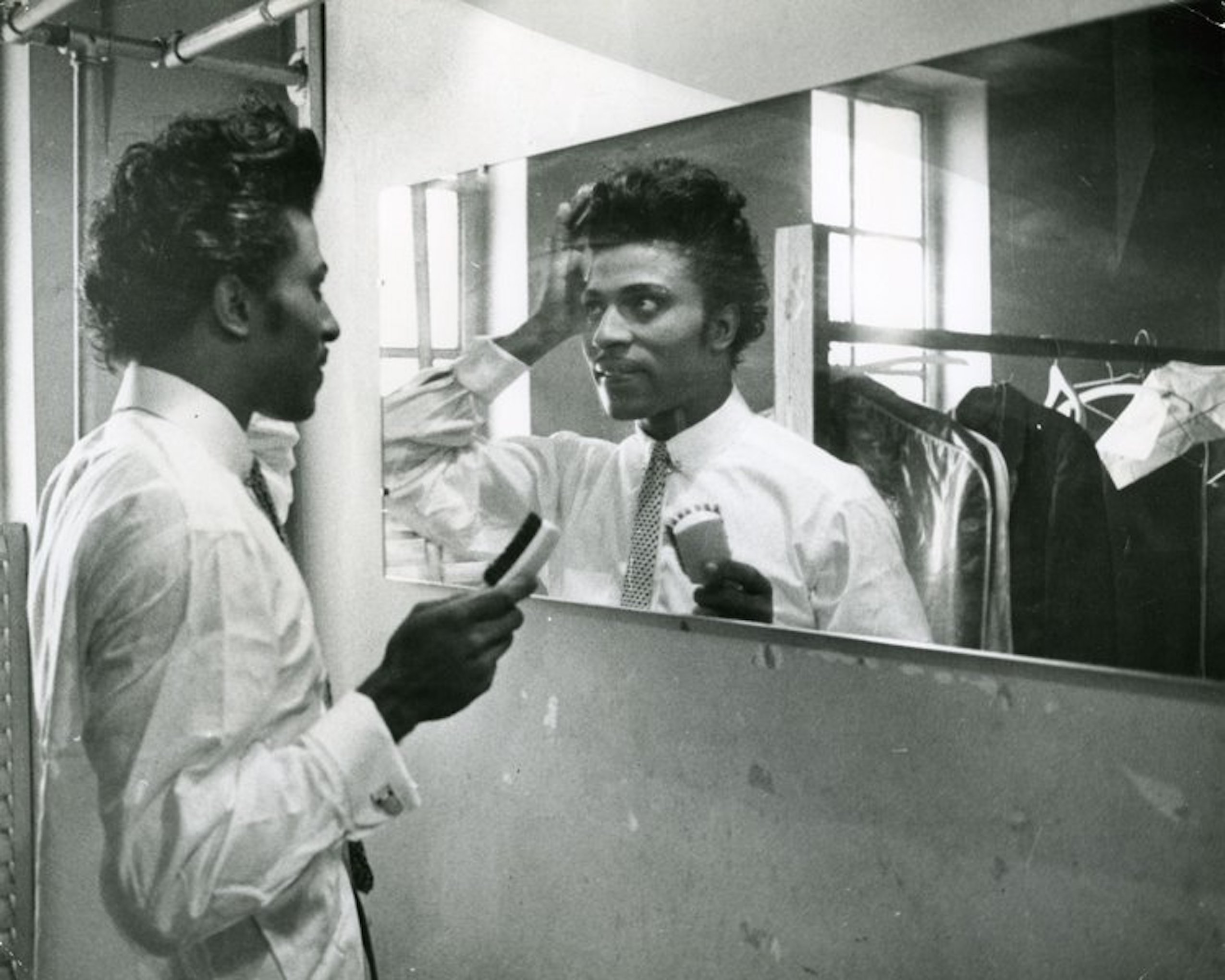

Combining fascinating footage and recorded observations from Richard Penniman himself and others, director Lisa Cortés has built an amazing insight into one of the most intriguing and perplexing performers of all time. The interviews are excellent, and she incorporates several sequences of current musicians re-enacting some pivotal moments of Richard’s career.

The film takes a mostly chronological approach, and Little Richard provides his backstory of growing up queer — “My daddy wanted seven sons, and I was messing that up.” Deep conviction in the church formed part of Richard’s bedrock, but a chance invitation in 1947 by the legendary Rosetta Tharpe for his first stage performance convinced him, at 14, that he had to get out of Macon, Georgia. Although cross-dressing and homosexuality were illegal nearly everywhere at the time, he was able to pursue both while performing on the so-called Chitlin’ Circuit.

The film also explores the seminal influences of Esquerita and Billy Wright, performers who pushed the edge of conventionality at the same time.

A couple of radio hits for Richard allowed him back into his dad’s approval. By 1953, Richard formed his own band and fellow musician Lloyd Price convinced him to get a demo to Art Rupe at Specialty Records. The label wanted a cross between B.B. King and Ray Charles, not the direction that Richard wanted to go. But one song had particular potential, after cleaning up the rather graphic lyrics about anal sex. “Tutti Frutti,” made radio-friendly, became ubiquitous, timeless, and crucial to the explosion of rock and roll.

As the single took off, it was covered (and smoothed out) by Elvis Presley and Pat Boone, eventually selling more than Richard’s original. “Long Tall Sally” became an even bigger hit, and was likewise covered by top white stars. At the time, transistor radios and radios in cars were how white people heard Black music, kept strictly separate in most other aspects of society.

The influence of the church and gospel music was never far from Richard, creating an inevitable tension with his biological inclinations. His star continued to ascend; by 1956 he joined a Black all-star tour, starting at the bottom of the bill, but by the end he was headlining. No one wanted to follow him. Despite firmly enforced segregation laws, white teenage kids gleefully attended his concerts.

Whether it was actually Sputnik, the Russian satellite, or, as he says, “seeing angels in the Australian sky,” in the late 1950s, Little Richard, at the peak of his career, dropped secular music and headed back to religion full-time. He enrolled in a very conservative Black religious school and recorded an album with the Quincy Jones Orchestra, doing very restrained sacred music.

By 1962, after marriage and a tour in England, our hero was back to playing his hits at ever more torrid performances.

“We were almost paralyzed with adoration,” said John Lennon when the Beatles shared a bill in Liverpool in late October 1962. In 1963, the Rolling Stones opened for Little Richard, and just as Paul McCartney had watched and learned from the side of the stage, Mick Jagger did likewise. Seeing Richard using the whole stage was a big takeaway for Jagger — that was unprecedented for the more static British artists then.

Whatever modicum of the straight life Richard tried to maintain, by 1967 he was divorced. In the early ‘70s, all sorts of drugs were part of his daily routine, and the church was again Richard’s refuge. “God let Adam be with Eve, not Steve,” he declared, and also claimed he had been gay, but was no longer.

“He was good at liberating others, but not good at liberating himself,” observes one music scholar, Jason King. Richard by then was selling Bibles and making church appearances, bringing in a relative pittance of income. John Branca, later famous as Michael Jackson’s lawyer, was called in to opine on the contractual inequities of labels failing to make payments. I would’ve liked to have seen more of this footage from that interview, as Branca tackled an all-too-familiar and pervasive blight in the music industry.

Interviews range from Tom Jones to John Waters, pointing to Little Richard as their primary influence (presumably delivering different influences). Nile Rodgers reveals that David Bowie wanted him to produce Bowie’s 1983 Let’s Dance album to sound just like Little Richard. (I wish I had known that when I found myself improbably sitting next to Little Richard a few years later, at a Bowie concert.)

Little Richard missed the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inaugural ceremony in 1986, at which he was inducted, because of a car accident caused by his falling asleep at the wheel. But he is rightly there, forever.

This is an excellent film, well worth your time.