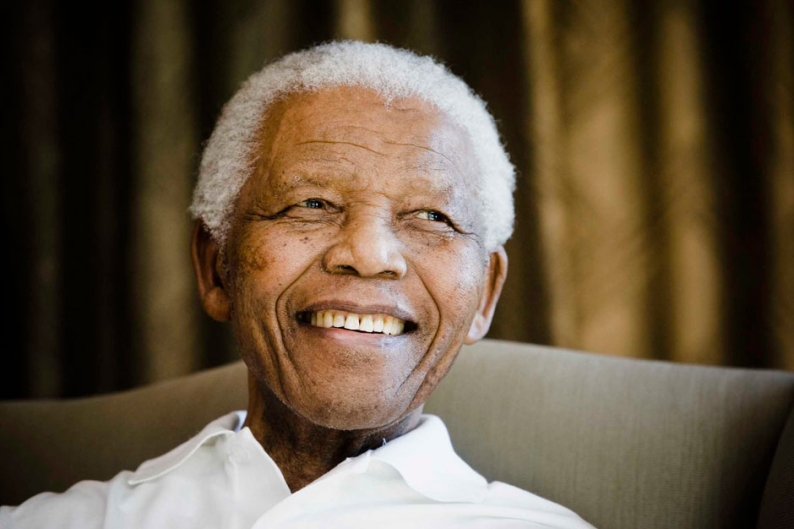

It has become common to hear complaints that activist music is unfashionable. It wasn’t always that way, of course. Nelson Mandela, the iconic South African leader, both inspired, and was inspired by, the intense relationship that pop music and politics, at their best, can demonstrate.

Mandela, who the BBC reports died December 5 at age 95 after receiving months of home care for severe lung infection, has secured a special place in history that will be analyzed and debated for years and decades to come. As the leader of the opposition to his country’s explicitly racist apartheid regime, he spent 27 years in prison, and speaking his name was forbidden. As South Africa’s first black president starting in 1994, he embraced racial reconciliation rather than division.

In the decade or so prior to Mandela’s release from prison in 1990, he also became the symbol of a global movement to end apartheid in South Africa. It’s here that his life intersects with the sorts of stories that SPIN usually covers. As with the late leader’s approach to governance, the songs that called for his freedom expressed hope rather than anger, unity rather than retribution. The “Free Nelson Mandela” movement inspired an array of musicians and demonstrated how socially engaged records can be successful, both politically and artistically, without being awkward or corny. It also, admittedly, illuminated the limits of pop activism.

Music was so tightly entwined with Mandela’s life that there is a whole documentary detailing the connection, last year’s Music for Mandela. South Africa has a richly varied, pioneering musical tradition, and Mandela tapped into the power of music to spread his message both before and after his imprisonment. He has spoken about how he drew inspiration from Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On while imprisoned, and he has also praised the Spice Girls. Quotes from Mandela may soon become as widepread (and sometimes misattributed) as those from Martin Luther King, Jr., or Mahatma Gandhi; still, this one credited to Mandela by the Los Angeles Times is too appropriate not to use here: “Artists reach areas far beyond the reach of politicians. Art, especially entertainment and music, is understood by everybody, and it lifts the spirits and the morale of those who hear it.”

Also Read

Compact Discs: Sound of the Future

From outside South Africa, the defining song of the anti-apartheid movement has to be “(Free) Nelson Mandela,” written by the Specials’ Jerry Dammers and recorded in 1984 under the band name the Special AKA. BBC America recently called it “the most potent protest song ever recorded,” and there’s a case to be made. It’s a direct, explicit call to action, but it’s also joyous and full of life. The song went top 10 on the British singles chart, and the awareness of Mandela’s struggles grew. Also, in 1987, British folk-soul singer Labi Siffre wrote “Something Inside So Strong,” a beautifully towering ballad that went to No. 4 on the U.K. charts and became a prominent anti-apartheid anthem, often associated with Mandela. Within South Africa, trumpeter Hugh Masekela was among those recording tributes to Mandela in the mid-’80s.

Even seemingly innocuous became political when associated with Mandela. In 1985, as the New York Times reported, South Africa’s government-run broadcasting company announced it would drop Stevie Wonder’s music from its playlists. The reason: When Wonder won an Oscar for “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” from the film The Woman in Red, he dedicated the award to Mandela.

In London on June 11, 1988, the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute concert was held before a crowd of 72,000 and a TV audience of an estimated 600 million people. Dammers performed “(Free) Nelson Mandela,” Peter Gabriel played his anti-apartheid song “Biko,” Bruce Springsteen’s longtime guitarist Steven Van Zandt did his anti-apartheid song “Sun City,” and Simple Minds brought “Mandela Day.” Other performers that day included Stevie Wonder, Whitney Houston, Sting, Salt-N-Pepa, Dire Straits, the Eurythmics, and many others.

And yet FOX scrubbed its broadcast of all the political aspects, even changing the concert’s name — to Freedomfest, naturally. As SPIN reported at the time, George Michael notoriously talked around the subject from the stage: “I know there are certain restrictions in certain parts of the world as to what people think this day’s all about. But you guys all know, yeah?” And, in a grim preview of 21st-century Swiftboating and “keep your government hands off my Medicare,” a group billing itself as the International Freedom Foundation reportedly passed out materials saying the concert was a fundraiser for terrorists.

When Mandela got out of prison in 1990, South African singer Brenda Fassie released “Black President,” another title that has become more resonant with time, though the house production and topical lyrics are dated. The newly freed Mandela traveled to America, where Spike Lee guest-edited an issue of SPIN that the legendary film director said was conceived in Mandela’s spirit. At that time, Mandela still couldn’t vote; Lee published a list of companies that even at such a late date continued to do business in South Africa. By 1994, apartheid was finally over and Mandela was president.

Since that time, no shortage of Mandela-related songs and tribute concerts have sprung into being. U2’s Bono and the Clash’s Joe Strummer co-wrote a song titled “46664,” after Mandela’s prison number, shortly before Strummer’s death in 2002. (The 46664 nonprofit began as Mandela’s initiative to raise global awareness about HIV and AIDs, but its dictate has now expanded to encompass a range of humanitarian and social-justice causes.) From 2003 to 2008, a series of star-studded 46664 concerts took place around the world, involving everyone South Africa’s Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Vusi Mahlasela to Beyoncé, Amy Winehouse, Robert Plant, and the surviving members of Queen. Such was Mandela’s cultural prominence that Smokey Robinson read a statement from him at Michael Jackson’s memorial four years ago. Bono recently paid tribute to Mandela again, on U2’s “Ordinary Love,” for the forthcoming biopic Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom.

The anti-apartheid movement underscored how music can actually effect change: by appealing to our common humanity, rather than that which divides us. You can hear its legacy in Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder writing a song for the West Memphis Three (Vedder also recorded a demo version of “Something Inside So Strong”). You can see its example in Big Boi rallying to free a man from Death Row.

Parodoxically, one of the albums that drew the most attention to the plight of South Africa was recorded in violation of the African National Congress’ cultural embargo: Paul Simon’s 1986 Graceland, recorded with Ladysmith Black Mambazo. As SPIN’s Andy Beta noted in a review of the Very Best’s 2012 album MTMTMK, since then “the world has turned upside-down…to the point now where the leader of the free world has Kenyan and Kansan blood in his veins, and 111.3 million Americans can watch a Sri Lankan refugee-turned-pop-provocateur give them a one-finger salute during the Super Bowl’s halftime show.”

M.I.A., of course, has continued her provocations, always spiking her polyglot dance-pop with politics. As a new generation of thoughtful music-makers, from Grimes and Savages to Chance the Rapper, continue to grapple with how to integrate their political ideals into music, Mandela’s story shows that sometimes the most effective protest songs are the most pointed and the most optimistic. Not all protests songs have the intended impact. But in Mandela’s case, the music he inspired not only helped free the long-imprisoned leader, but sustained and helped free his people. As Mandela put it: “Music is a great blessing. It has the power to elevate us and liberate us. It sets people free to dream. It can unite us to sing with one voice.” Of course, Mandela’s legacy is far bigger than music, but he understood that music was also a big, even essential, part to that legacy.

More on Nelson Mandela:

Nelson Mandela’s Death: Twitter Reacts

Nelson Mandela’s Subversive Musical Legacy

Barack Obama: ‘Nelson Mandela Bent the Arc of the Moral Universe’