On September 15, 2015, nearly 20 years after it was first released, GZA finally received a platinum record in the mail from the RIAA for his seminal ‘90s masterpiece Liquid Swords. “It’s a good feeling,” he said of the honor. “It took a while.” No kidding.

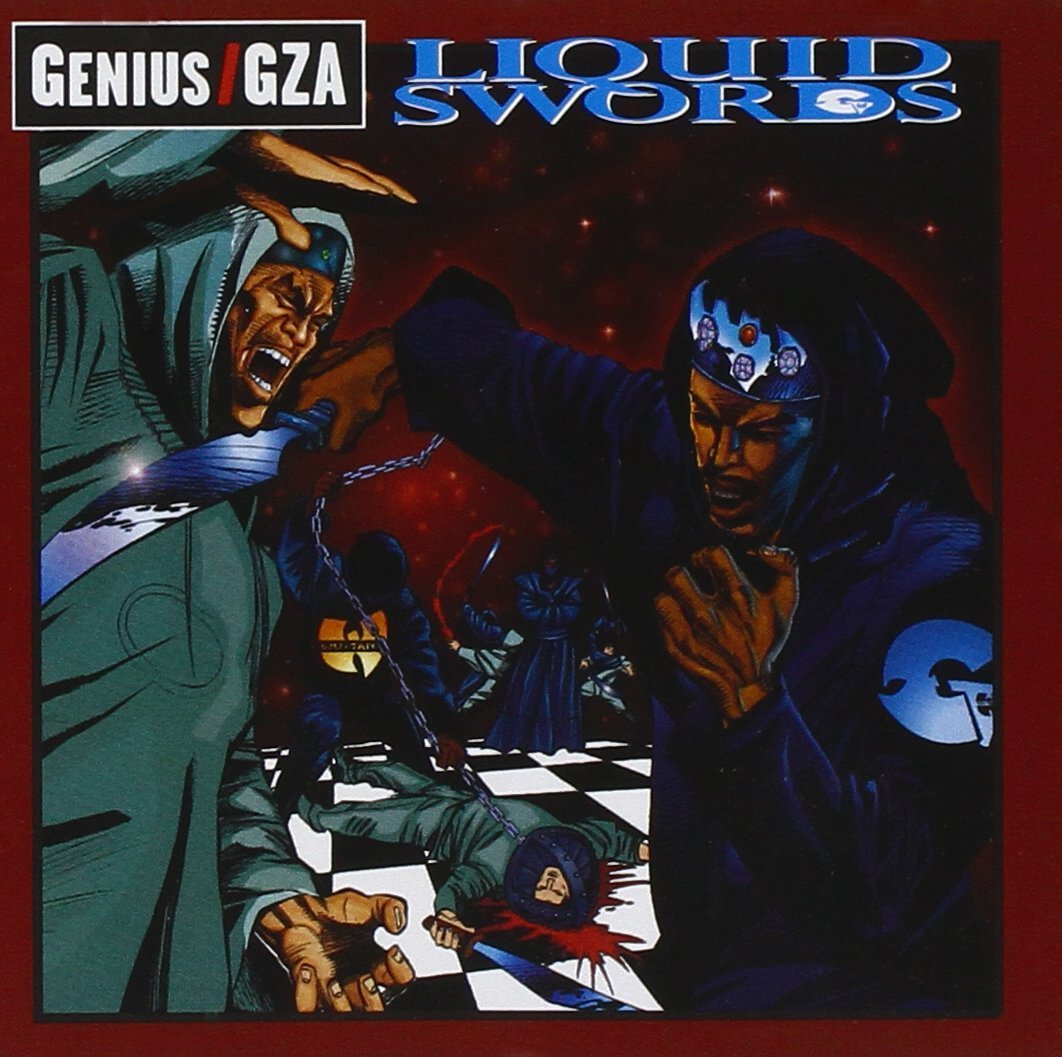

When it debuted in November of 1995, Liquid Swords — one of SPIN‘s 300 Best Albums of the Last 30 Years — was part and parcel of a larger plan put into place by the members of the mighty Staten Island-based rap collective known as the Wu-Tang Clan (and its leader, RZA) to take over the rap game. It all began with the collective’s 1993 full-length debut, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), and was expanded over the next few years with the solo releases of Method Man’s Tical, Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version, and Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… All three of those solo albums clearly have their own signature flavors and motifs, but hardly any of them could match the cinematic flair, the tight and cohesive thematic strain, or the dense lyrical verbiage of Liquid Swords — the best-remembered LP from the group’s most famously verbose member, familiarly known as the Genius.

In honor of Liquid Swords‘ 20th anniversary, SPIN recently hopped on the phone with GZA, an MC with one of the most formidable arsenals of words in hip-hop history, to talk about how the record came together, and to walk us through the process of creating his singular rhymes.

Liquid Swords was your second solo record, but your first after solidifying the Wu-Tang Clan and releasing Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). How did your approach change between Words From the Genius in 1991 to this record in 1995?

Also Read

GEAR THAT MADE THE GAME: Rap Machinery

I don’t think that the approach had really changed at all. I just think that the subject matter had broadened.

What was on your mind at the time that you were making Liquid Swords?

Everything. I get inspired by many different things. It can be an object, it can be a person; there were many things on my mind when I started working on this album. I really, really wanted to show my lyrical ability and my storytelling style and it felt like I had certain things to prove because of [promotional issues] in the past from the prior label I was on [Cold Chillin’ Records]. So I felt that I needed to just slash back.

You’ve been credited as having one of the largest vocabularies in rap history by unique word count. Do you make a conscious effort to try and incorporate a lot of different words into your writing or does that just come naturally?

It’s just kind of me. It’s always been like that since we were teenagers when we formed our first group called All in Together with RZA, [Ol’] Dirty [Bastard], and myself. Emceeing has always been about making the most intellectual, most creative, wittiest rhyme as possible regardless of any subject. It was always about bringing the best out of yourself.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=9oKUu1fO9KM

There’s always been this competitive spirit within the Wu-Tang Clan. How has that impacted the way your write and record?

In different ways… I mean, when you have nine members within a group and they’re all in the studio writing to the beat, there’s a lot of pressure, so the competition is always there and it helps you advance. Sometimes you might hear a rhyme like, you know, for instance, when I heard [Inspectah] Deck’s verse on “Triumph” [from Forever in 1997] it was hard to follow that.

RZA has mentioned in past interviews about his vision for the Clan to reach different sets of demographics with each of the individual solo records and mentioned that Liquid Swords was an effort to reach the college crowd. Did you buy into that?

No. He may have said that, but that just wasn’t my aim, to get college kids. I mean, I think as an artist the overall goal is to teach and educate no matter what the song is about. Somewhere where a listener can get something out of it, something that can give them help to move forward, help them learn something, analyze something in a different way, or think about something.

It may just have been that college kids were more interested in learning and dissecting and researching and trying to figure it out. That’s just how it unfolded, but that wasn’t really part of the plan. I strive to get everyone.

Is there a group of people that you think this record doesn’t really speak to?

With the profanity on it, I would say that it’s not suitable for children or young kids… You know, at one time I stopped using profanity on lyrics. I mean, it was many, many years ago, but I had a line off 2002’s Legend of the Liquid Sword album where I said, “I’m the obscene slang kicker, with no parental sticker / Advising y’all that wise words are much slicker.” It would be a universal record as far as hip-hop though, with the beats and the way the rhymes are put together and the style of it and the certain things I’m speaking about.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=zZtS1BzdNpw

What was it about the film Shogun Assassin, which was sampled for the opening of the record that resonated so much with you? When did you first see that one?

You might be surprised by this answer, but I don’t think that I watched the movie until after the Liquid Swords album [was released].

So including the dialogue from that film came purely from RZA, then?

Yeah, RZA did that in the last stages of the album. We were actually beyond mixing the album, the album was mixed already and we were mastering the album and he sent the engineer out or someone from the studio and said, “Bring me back Shogun Assassin,” and threw it on the album. That came at the very last minute.

Can you talk about your relationship with RZA, how you two collaborate as writers and how he approaches you as a producer?

I think the chemistry is great. Before RZA started producing he was a DJ… well, a DJ, an MC, and a beatboxer. So was Dirty. As far as myself, I was just an MC and I did a little graffiti back in the day, but I wasn’t one of the great artists who had their name and work walls posted all over the neighborhood and stuff. But before RZA was a producer, he was an MC, then he became a producer but he was also a human beat box specialist.

Plus we were in a group together as teenagers. We were always rhyming and battling so we kind of knew each other’s style and flow well. He was aware of that going into this project and the chemistry is great. And him being an MC, he would sometimes ask me to switch a rhyme around, throw a line in there, ask me if I could say something in a different way or if I could change the flow of it. I understood a majority of the time where he was coming from.

You have a unique and frankly dense storytelling method. How do you put together something like “Gold,” which is about coming up through the criminal underground? There’s a lot of metaphor in that song.

It’s just an urban street tale and when I want to tell an urban street tale, I try and tell it from a different perspective than the average way you would hear a story. I have different ways of doing it, like on “Clan in Da Front.” I’m not a sports person, but every now and then I incorporate sports in my rhymes because I’m always grabbing from certain things and getting inspired by something whether I’m totally involved in it or not. So on “Clan in Da Front” there’s a line where I say, “I’m on the mound, G, and it’s a no-hitter / And my DJ the catcher, he’s my man…” That’s more braggadocios.

But on “Gold” I’m like, “I’m deep down in the back streets, in the heart of Medina / About to set off something more deep than a misdemeanor…” So it’s really about hustling and street activity, but it’s just told in a different way.

Speaking about doing songs in a different way, how did you get the idea to open “Cold World” in a “Night Before Christmas” framework?

That’s just how my mind thinks. The great thing about writing is that you create your own world and you bring listeners into your world depending on what you write. I’m always hearing something or seeing something that has some sort of inspiration in it. Even if it’s not so good, I can try and pull the good or the beauty out of it. I just thought it was a cool start for that story.

Every single member of the Wu-Tang Clan is present on Liquid Swords in one way or another. Was there a conscious effort made to include everyone?

It’s always great to have the help and support from your brothers, especially within the Clan… I was always open to having anyone and it was the early stage of Wu, and thought it would be great to have a member on the album, but I didn’t necessarily want to depend on that to complete an album. You know, nowadays artists put out albums and they have 50 different features or guest appearances on the album and it kind of overshadows them sometimes. As an MC for so long, we were used to holding our own weight.

The album I did before Liquid Swords, Words from the Genius, didn’t have any Clan members on it even though they existed at that time. RZA wasn’t on it, Dirty wasn’t on it. I approached the album with open space for any of my Clan brothers to get on, but if not, I had to be able to fill that space.

How collaborative are you as a writer?

There are certain lines that I’ve taken from other artists. I mean, on “Living in the World Today,” the second verse, some of that came from RZA. Like, “My preliminary attack keep cemeteries packed,” that came from RZA. Then on “Cold World,” there’s a line where I say, “And it does sound ill like wars in Brownsville / Or fatal robberies in Red Hook where Feds look.” I got “Red Hook” and “Feds look” and “Brownsville” and “sounds of steel” from [Killa] Priest and then I happened to put them into a sentence. I’ve taken little lines and pieces from some of my brothers.

You know there’s a saying that two heads are better than one. I’m used to writing alone, but a lot of times it helps out if you have another MC around you because he can feed stuff to you.

Liquid Swords is very cohesive, both in theme and overall sound. Was that more of a byproduct of your headspace at the time or did it end up like that from RZA’s input as the producer?

It was a combination of both… the beats have to complement the rhymes, and the rhymes have to complement the beats. It’s just my job to make it cohesive lyrically and make everything fit, not just telling a story, but weaving a tale. That’s just my approach to lyrics in general. I’m always trying to make it tighter and tighter, draft and draft, then re-draft and re-draft over and over. I change sentences; I change words until I feel it’s right. And then, even after I feel it’s right, several years later I revisit it and say, “Well, I could have said that like this,” because I’m always growing and developing.

You’ve described this album in the past as being cinematic in scope, and you’ve used cinematic terms when describing it. You also directed music videos for four of the songs off Liquid Swords. What is it about the medium of film that inspires you musically and makes you think about it from that level?

Well, film is a visual thing, you know? And rap is a visual language. It’s about creating the most visual rhyme you can create because when someone is listening they have to be able to draw pictures in their own head. You just strive to make the rhyme as visual as possible. You want to make it cinematic.

When people talk about this record — as well as a lot of those other great mid-‘90s Wu-Tang records — the word that comes up a lot is “gritty.” What do you think it is about that sound and the themes you guys mined that has endured in the minds of so many people for so many years?

Timing was one. It was something new and something fresh. Something unheard of in that way. I mean, there’s nothing new under the sun, but there’s always different ways of approaching something or revising something. I think the grittiness is just a part of where we come from. You know, rough, rugged around the edges. It’s rap and maybe not nowadays, but the origin of it was rugged and rigid and gritty.

What songs off of Liquid Swords do you think hold up the most for you today and what songs do you like performing the most live?

I like performing “Liquid Swords.” I like performing “Duel of the Iron Mic.” That’s one of my favorites. “4th Chamber” because of its energy and the guitars and the whole crazy-sounding rock sort of thing. That’s one of the songs we perform whether I’m solo or with Wu. It’s maybe one of two or three songs that the crowd is at its hypest and sometimes we stop it after ten seconds and play it back just to get more of a reaction from the crowd.

It’s been reported for years that you ghostwrote a lot of the verses to Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s record Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version. Is there any truth to that?

There is. I mean, I’ve used a little bit of Dirty’s stuff also, but the thing with the rhymes that were on Dirty’s album was that these were rhymes that were written when I was a teenager and those rhymes didn’t really suit or fit me at the time and Dirty had a way of taking stuff and making it his own. It just fit him more than it fit me. One of the rhymes [from “Don’t You Know”] he says, “Sittin’ in my class at a quarter to ten / Waiting patiently for the class to begin / The teacher says student please open your texts / And read the first paragraph on oral sex.” I wrote that as a teenager! So by the time I was doing Words from the Genius or Liquid Swords, I didn’t want to be kicking those rhymes. It would have been more of a Fresh Prince thing to me. Not to take from him or disrespect him, but that was his kind of style.

After you released Liquid Swords you shortly thereafter started working on Wu-Tang Forever with the whole Clan and then went on the infamous tour with Rage Against the Machine in 1997 that ended rather abruptly. What happened that caused that particular tour to break up before the end?

I don’t really know what it was. We were on tour and then we were doing the Summer Jam concert and we had to miss a show and…we didn’t have to leave the tour but we had to miss a show or two to do the Summer Jam thing. We voted on it and some of us said we shouldn’t do it, and some of us thought we should do it, and we ended up doing that. It ended up turning out to be a disaster in one way for us to even do that show but somehow we didn’t go back on the Rage tour. For what reason I do not know. We weren’t kicked off the tour, it was our decision to not… I mean, not mine personally because I just would have stayed on tour and kept rocking. We were rocking in front of big crowds, there was great response and you know, it was just the decision and it didn’t work out.

What can you say at the moment about your upcoming record, Dark Matter? You posted a photo on Instagram recently in the studio with Vangelis, the composer of Chariots of Fire.

I think that this is going to be a very, very great one, maybe the strongest by far. Lyrically, definitely. I’m still working on it, but the musical approach is quite different now that Vangelis is in the picture.