LIVE GEAR

Hip-hop live performances started out slim and simple: two turntables and a microphone, along with the unsung hero, a simple mixer with a sturdy crossfader. Throughout the 2000s, concert presentations expanded and full backing bands began to play with many of hip-hop’s largest acts, and though these days many rap shows have become full-on multimedia spectacles, certain choice models of those three day-one indispensables have never changed, and probably never will.

Shure SM58 microphone

Whether you realize it or not, you’ve seen, and certainly have heard, the Shure SM58 microphone, an indispensable tool for capturing vocal performances in all live venues, from DIY punk houses to symphony halls, coffee shop open-mics to hip-hop clubs, all the way up to arena rock extravaganzas. The SM58 is also the most popular choice in music to capture the sound of a guitar amplifier, acoustic instrument, drum, saxophone or trumpet — it also happens to be the exact microphone model sitting on the president’s podium for every commander-in-chief speech.

The SM58 is called a dynamic mic, in that it gathers sound best at close range, only from the direction it is pointed at — musts for live rapping — as opposed to a condenser mic, which captures sounds from all around it and is very sensitive (thereby typically reserved for studio rhyming). The 58 utilizes a cardioid signal pickup pattern to capture audio at equal levels from different proximities to the mouth (without picking up unwanted sounds). This is to say, whether the SM58 is against your lips, four inches away, or moving back and forth, its pickup designed to keep vocal levels relatively steady.

The SM58 is also pretty seriously built. The mic’s proprietary “pneumatic shock-mount” system allows MCs to get aggressive without causing excess handling noise, and also makes some now-and-then mic gymnastics possible (Go ahead, drop the mic, the SM58 was the one Obama so famously dropped … feel free to do some Mars Volta, swing it around a bit, the XLR cable-lock will hold. Probably.) Its interior is pretty fierce as well — like the best condenser mics, an SM58 pickup can endure extreme volume levels and still transmit sounds without popping or crackling noises.

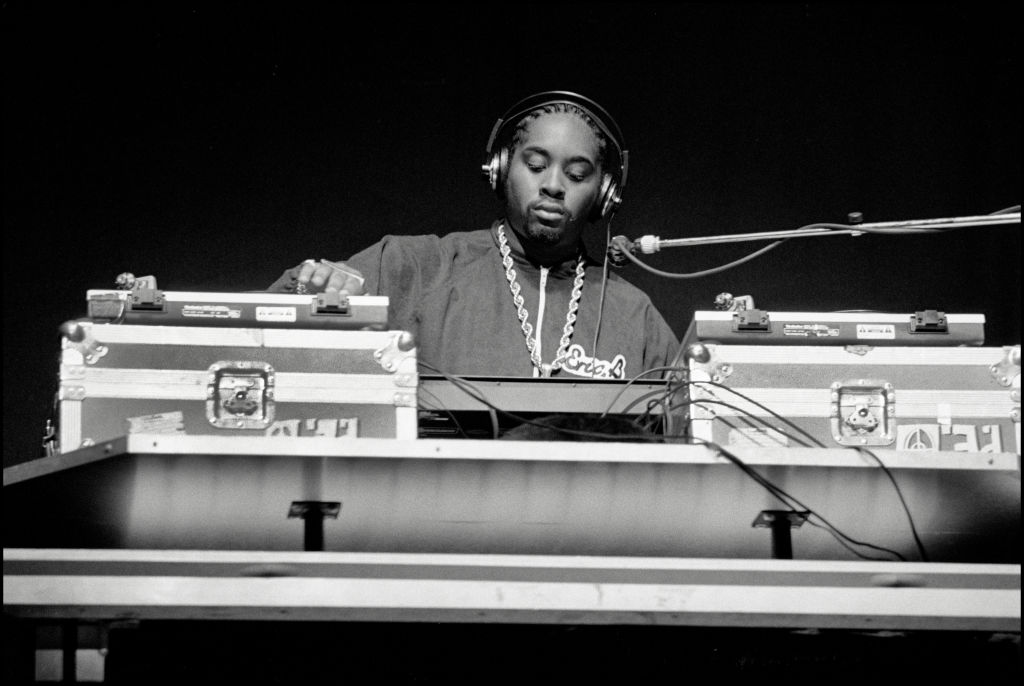

Technics SL1200 Turntable

First and foremost, the SL1200’s hip-hop appeal involves the specific method it uses to spin the record platter. As all true DJ decks must be, the 1200 is a direct-drive turntable, meaning the platter is spun by a motor directly below it, as opposed to a belt-drive turntable, which features an offset motor spinning a belt attached to the platter, rotating it independently. On a belt-drive, after a record is touched it takes a moment to return to full speed, whereas direct-drive tables return to speed almost immediately, due to the motor’s physical connection to the platter. Belt lag is a set-killer for any serious DJ: the equivalent of playing streetball with your laces untied.

Direct-drives are also much more dependable (and expensive) devices, as belts are prone to wear out or snap during a scratch. Belt-drive tables typically have no pitch-control sliders either, only 33 or 45 RPM speed selectors. Pitch sliders are a key tool for DJs fine-tuning tempo matches while crossfading songs, as well as a great hack for creating different notes with just one scratch sound. Despite the rise of designer belt-drive tables, and catalog pages worth of SL1200 knockoffs, the OG, high-end, direct-drive Technics remains the must-have for any turntablist worth their salt — and that’s without even considering stylus-arm performance.

For a turntablist, it’s vital a stylus never skips the groove, even during vigorous scratching, so the SL1200 provides a sturdier, more finite counterweight than most. (As anybody worth their wax knows, a counterweight is the battery-shaped metal cylinder on the far end of the stylus-arm.) With pressure set to 0, the arm floats level in the air, and as the pressure is raised, a downward force is imparted on the stylus, allowing it to catch a record’s grooves. As all listeners do, a DJ seeks a happy-medium pressure that holds grooves without eroding them, though a counterweight that stays still during forceful scratching is a DJ’s number-one concern, and the SL’s certainly stays put.

Technics SH-DJ1200 Mixer

While simple, tabletop DJ mixers are rarely the stars of any live show, the Technics SH-DJ1200 sits in the center spotlight of the DMC (Disco Mix Club) World DJ Championships, a near-40-year old global DJ competition that serves as the Olympics for turntablists. Though hip-hop DJs traditionally aren’t as picky about their mixer as they are their turntable and cartridge, there are definitely a few musts to consider when selecting a hip-hop-appropriate mixer — a seriously sturdy build (the cross-fader must endure any and all abuse), wiring that carries signals without any loss of fidelity, and trusted circuitry capable of holding its solders during the beatdown of a scratch routine.

While typical club mixers are wide devices that take 4 channels or more of input, and utilize tiered stages of volume control adjusted by multiple knobs, the DJ1200 is a slim, no-frills, two-channel mixer designed with minimal controls and three simple faders. During serious scratch routines, any knobs not being utilized become obstacles, so Technics kept the bottom two-thirds of the DJ1200 design as an open area, to allow for quick and easy hand moves. All this and it shares a brand, model and make with the choicest hip-hop turntable of them all, Technics’ SL1200? Easy decision.

STUDIO GEAR

DJ Kool Herc’s “Merry-go-round” technique for sewing breakbeats together using two turntables — the one he debuted at his legendary party on August 11, 1973 in the Bronx — laid the foundation for studio rap, but without early samplers and sequencers, beats as we know then today simply wouldn’t exist. Here are three of the most iconic pieces of beat-production equipment in the history of hip-hop, each featuring unique sound characteristics dear to millions of listeners across the globe.

E-mu SP1200

After Biz Markie inadvertently became the poster child for the dangers of using unlicensed samples to make beats, rap producers everywhere were forced to adjust their technique, utilizing samples from more obscure songs, filtered and rearranged to prevent recognition by the sampled artist (and thereby, hopefully, avoid a lawsuit and loss of ownership rights to their new song.) This shift also coincided with the stellar rise of device perfect for this new production method, E-mu’s SP-1200, a completely portable sampling workstation capable of production tasks that had previously required a full studio’s worth of equipment.

The SP-1200 did, however, did have some downsides. It processed audio at a 26 kHz & 12-bit resolution rate (as compared to studio-standard 48 kHz & 24-bit), leaving the outgoing audio with noticeably less clarity than the incoming audio samples. In addition, the SP featured only 2.5 seconds of sampling time per sound slot, leaving producers who were accustomed to building beats with large chunks of music feeling handcuffed. A dilemma for sure, but one now-famous production hack used to extend sample times ended up inadvertently changing the sound of hip-hop forever.

Intrepid beat-smiths realized that if audio was recorded into the SP at a high speed, then digitally reduced in pitch, the resulting audio would be stretched into a longer, more usable form — in the process however, the sound took on a grainy, digital crunch. Though decidedly lo-fi, this sound texture soon became an endearing, trademark aesthetic of SP-1200 produced beats. An additional “swing” control, used to loosen the timing of programmed drums, also provided the SP with a distinctive rhythmic touch beloved by rap fans. This mini-doc on the SP-1200 includes a live demo and expanded history.

3x CLASSIC SP-1200 BEATS

House of Pain, “Jump Around”

AKAI’s MPC Series

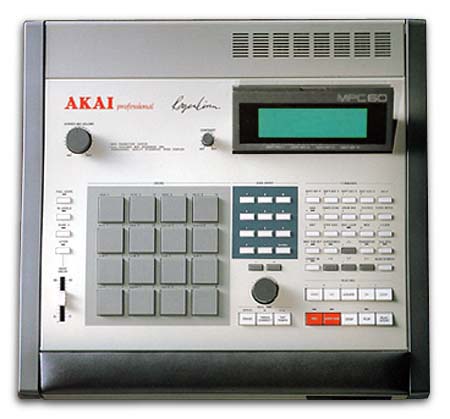

Aside from the SP-1200, no single piece of equipment has had greater impact on hip-hop production than the MPC-series sampler, the most hallowed of which, the MPC-60, was built in 1988 by audio engineer Roger Linn in conjunction with Japanese electronics brand Akai. Linn first rose to prominence as a gear engineer in 1980, when fed up with loop-only drum machines featuring stock presets (that he says “sounded like crickets”), he designed and built the LM-1, the very first device of its kind to feature samples of actual acoustic drums, and one of the earliest to offer detailed programming capabilities (Prince was a massive fan, using one of the first LM-1s on “When Doves Cry”, “Raspberry Beret”, and throughout his career.)

The MPC-60 was the result of Linn’s quest to re-engineer his Linn 9000 (first built in the mid-80s after the LM-1 took off), with the goal of creating an affordable beat-machine that didn’t require deep knowledge of music or studio wizardry to use. The result was a sampler with double the trigger pads as an SP-1200 (more sounds to use all at once), relatively better audio quality (still 12-bit, but no grainy, digital crunch), and thanks to larger memory banks, longer sampling capabilities. In 1991, Akai and Linn released their follow-up, the MPC-60 II, the only upgrades being a headphone output, and plastic rather than metal casing (billed as easier for producers to carry from gig to gig).

1993 brought the MPC-3000, quite a hefty model-number upgrade, but a merited one — the jump to 16-bit 44.1 kHz stereo sampling and addition of built-in audio effects and filters were both huge advancements. In 1997, Linn cut ties with Akai after the company removed his name from the MPC line, in order to eliminate royalty payments. Nonetheless, Akai barreled on, that year releasing the MPC-2000, a compact version of the 3000 with even more sampling time and memory, to which Linn commented: “Akai seems to be making slight changes to my old 1986 designs for the original MPC, basically rearranging the deck chairs on their Titanic.”

Like the SP-1200, all MPCs have a “swing” control, though purists claim the MC-60’s swing is inimitable. At least one of the game’s most immortal beat-smiths felt otherwise — the late J-Dilla swore by his 3000, which is currently on display in the Smithsonian.

3x CLASSIC AKAI MPC-SERIES BEATS

Roland TR-808 Rhythm Composer

Produced and sold between 1980 and 1983, the legendary TR-808 Rhythm Composer is best known for the massive subsonic swell of its built-in kick drum, a sound so recognizable across all genres that is has simply become known as an “808”. As a drum machine and sequencer, the TR-808 was especially unique in that it afforded producers the ability to compose entire original rhythm sections—rather than simply manipulating and triggering simple preset drum loops built into keyboards and samplers. Adding to the machine’s appeal was a hefty 64 slots for users to save their programmed drum patterns, as well as entire song sequences made of those patterns.

The TR-808 also made it possible for beatmakers to customize drum rolls, fills and stutters, to be triggered on the fly with the push of a button, allowing for improv in the same manner and timing as a live drummer. Adding to the 808’s customization factor was an accent control, used to raise the level of specific sounds in relation to those around it, allowing producers to tweak the sound dynamics of the beat as a whole. While digital devices of the time did allow for much more lifelike drum sounds than the analog TR-808, hip-hop’s traditional preference for quirky sounds over clean ones (and the TR’s lower price point), made the device an early beat-making stalwart.

Amazingly, one specific TR-808, which resided in NYC’s legendary Chung King Studios during the 80s as in-house device, is credited as being the magic ingredient in some of the most formative albums in hip-hop history, including the debut albums of Run-D.M.C., the Beastie Boys and LL Cool J. Legend has it that Def Jam co-founder Rick Rubin, the producer of these LPs, customized the device’s circuitry to produce a thicker, longer-lasting bass drum sound than those on any stock TR-808. This true Holy Grail of rap production devices was purchased by Ad-Rock of the Beastie Boys upon Chung King’s shuttering.

A full documentary was made detailing the 808’s impact on the music industry, and for a brief look at the TR-808 in action, check this brief demo.