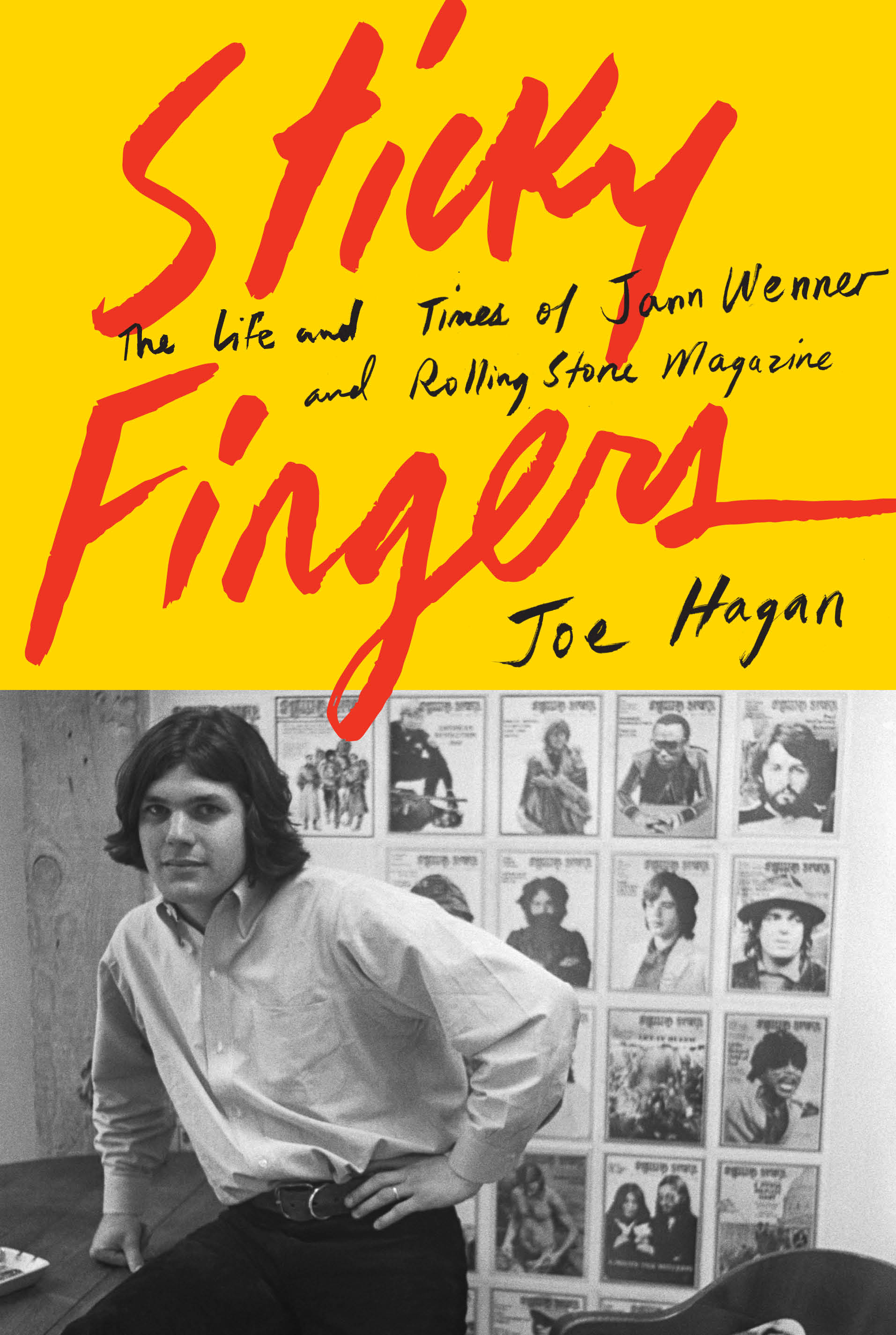

Jann Wenner doesn’t want you to read Sticky Fingers, a new biography about the life of Jann Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone. That’s too bad, because the book deserves to be devoured by anyone interested in the history of Rolling Stone, and more broadly, how it shaped and tilted cultural attitudes over the last half-century. Meticulously researched and filled with fascinating anecdotes and gossip items, Sticky Fingers is a definitive account of the man who possibly more than any musician impacted the way America consumes and thinks of rock n’ roll.

Wenner was just 21 years old when in 1967 he decided there was a burgeoning desire to see rock n’ roll, which was up until then a genre of music easily dismissed as a teen fad, covered respectfully and enthusiastically, without lapsing into pretentious academic speak. Named for the Bob Dylan song (and not the band), Rolling Stone crystallized the feelings of ’60s youths who knew this music mattered, no matter what the adults said. “You can’t explain to someone today how unique and essential those things were to the fiber of your being in those days,” Bruce Springsteen tells Joe Hagen, the author. “They were the only validating pieces of writing that [showed] somebody else out there was thinking about rock music the way you were. That was comforting.”

Born to modest wealth to parents who quickly divorced, Wenner was less a proponent of the counterculture than a man who sought power. (He hid his homosexuality for his entire youth because his marriage to the stylish and smart Jane Schindelheim, a key component in the magazine’s formative days, allowed him entrée into increasingly fancy circles of social influence.) When it launched, Rolling Stone‘s only competitors were teen magazines and quasi-underground publications like Crawdaddy. Rolling Stone‘s innovation was to professionalize its approach, aping its clean design from the existing Sunday Ramparts magazine (which Wenner edited before it folded) and grounding its writing with a more technical approach. It was not a bastion of journalistic integrity: Big artists were often afforded final approval of their interviews, and lesser artists were permanently snubbed because of Wenner’s private pettiness. (Paul Simon, who had a fling with Wenner’s ex, was minimized for years in the magazine.) But it had access, energy, and beautiful photographs—enough to make it a leading document of youth culture.

Rolling Stone‘s best ideas often came at someone else’s behest. Co-founder Ralph Gleason suggested putting out an open call for reviews, which produced writers like Lester Bangs; editor-in-chief John Burks forced the magazine’s interest in politics following the Kent State and Jackson State shootings, spearheading a landmark issue that Wenner nonetheless tried to take credit for. Wenner’s real genius was for leveraging his power to push Rolling Stone as the establishment, and with it, Rolling Stone‘s idea of rock n’ roll. Very quickly, Wenner showed he had no real allegiance to the radical politics that accommodated the music, despite the whims of his employees. (He feuded with notorious revolutionary activist Abbie Hoffman, who Rolling Stone had accused of being a fraud.) But he did care about saying what was important. Hagan argues that the way Wenner protected John Lennon’s image following the Beatle’s tragic death calcified the musical canon where the Beatles were permanently on top, as did his heavy involvement with creating the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The counterculture may have rolled its eyes, as did the staffers, but they couldn’t afford the cars displayed in the magazine’s increasingly ritzy advertisements.

Also Read

Rolling Stone Launches Music Charts

Rolling Stone‘s first epochal shift came at the end of the ’70s, when disco and punk weren’t selling magazines, and the magazine made a pointed effort to validate the ongoing work of the previous decade’s stars, as a way to insist on the value of its own critical judgment. Who else but Jann Wenner would’ve written, at the time, that Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming was possibly his greatest record? A juicy item comes when Hagan reports U2 topped the year-end albums list in 2014 with the anemic Songs of Innocence because of Bono’s friendship with Wenner, and Wenner’s need to wield Rolling Stone as a cudgel against those who would poke fun at his friends. “My dictate,” he says. “By fiat, buddy. That’s that.”

Rolling Stone was rock music’s first truly important publication. It wouldn’t be the last: Spin, which pops up toward the end, leapfrogged to a place of influence by featuring the alternative artists that Rolling Stone wouldn’t (U2, L7, Pixies); Pitchfork, which isn’t mentioned, rose to power by establishing a firm online presence when many publications thought the internet was a fad, and by publishing honest, critical reviews that a new generation of young readers could trust over the hagiography found in Rolling Stone. (Wenner’s tone deaf concept of the internet is covered in the final section, which mostly discusses how Rolling Stone‘s influence began to wane.) The compromise was simple: To stick with the times, Rolling Stone constantly abandoned its original tenets. It pursued corporate advertising; it stuck lame artists on the cover; it wholly protected the stars because of the access they gave, rather than puncturing holes in their image the way the earlier, more rambunctious issues might have.

Wenner’s reticence over the biography relates to the tonnage of testimony from former friends and co-workers explaining what a jerk he could be. He shared gossip that wasn’t his to share; he underpaid people because he knew he could; he sold out artists by betting they’d eventually forgive him, because of his position. A telling story comes when we learn a crew of former Rolling Stone staffers decide not to invite Wenner to a forty-year reunion. The trade off is explicitly delineated. Wenner may have interviewed heads of state, befriended rock stars, flown in private jets, become a media mogul, and lived as enjoyable a life as could be found under late capitalism. But he inspires bromides from people who once loved him, and displays little capacity for grasping the depths of why anyone would have an issue with a formerly insurgent institution that exploited the counterculture.

I finished the book impressed by Wenner’s accomplishments and force of will, but wary of how he made an active choice to hollow out his humanity, flipping on confidantes once they were no longer of use and always picking the route that would give him the most money. (An exception is when a proposed sale to Hearst in the early 21st century would’ve made him a billionaire; he turns it down because he would’ve had to give up control of Rolling Stone.) This kind of hunger passes down through generations: Toward the end, Wenner’s son Gus is introduced to us as a mini-Jann, one who has absorbed his father’s capacity for ambition from a young age. His first act, after being installed as the head of Rolling Stone’s website at the tender age of 25, is to fire a dozen staffers. “I believe so much in the cause,” Gus says when asked if firing experienced staffers is weird. “And there’s so much on the line between what the brand represents, myself, and my family. The well-being of my family.”

A cynical read of Rolling Stone says this is its true goal, as a vehicle for the Wenner genius. But 2017 is different from 1967, and the younger Wenner’s confidence only counts for so much. The book’s story was still being written up until the present; just a month ago, Rolling Stone put itself up for sale, with the expectation that the business will drastically change. (Like everyone else, they will be pivoting to video.) It is easy to see Wenner as a depleted giant, a man who bet all he had on richness and relevance and may retire without either. Yet Hagan’s conclusion is gentle. If it takes an asshole to change the world, then it takes an asshole. For better or worse, we can definitively say the history of modern music and music journalism would be different without Wenner.

“When you held it in your hands, you held Jann Wenner’s love letter to the culture, to himself,” Hagan writes. “Every other week for fifty years. And now it was all but buried, part of the vast American archive. But nobody couldn’t say Jann Wenner hadn’t given himself to it completely. He was an incorrigible egotist, but he had made up for it with a life of impact. He had mattered. He broke things; he made things. A nude John Lennon curled around Yoko Ono—nobody would ever forget. An entire American cosmology of superstars and superstar journalists, stories, and myths, all fired in the kiln of his appetites and ambition. Millions had dreamed on his pages.” I did, and perhaps you did, too.