Sonic Youth made some godawfully strange sounds sometimes. Ghastful, living, breathing sounds—summoned instead of played, coaxed from the kingdom of extreme volume, gorgeously scorched, stretched and fried, doused in voltaic energy, and wielded by the band with a wide-eyed, childlike fascination. All of this, while retaining the average listener.

More than just play songs, Sonic Youth explored how sound itself could be made to behave, to mesmerize and terrify, in beautiful, horrible-sounding ways, with tuneful music made of uncategorizable noise. Few comparisons exist in this realm, precise descriptions are difficult; man’s languages fall short. Wild theoretical portraitures are called for:

The sound of melting light, and time inverting.

Assaulting science and aborting gravity.

The sound of crying incense, smoking plutonium, and painting with knives.

Screaming in hieroglyphs, tearing space open, barfing lava and pissing neon.

Annihilative frequencies of utter bedlam, that when played in a catchy context, earned major label release.

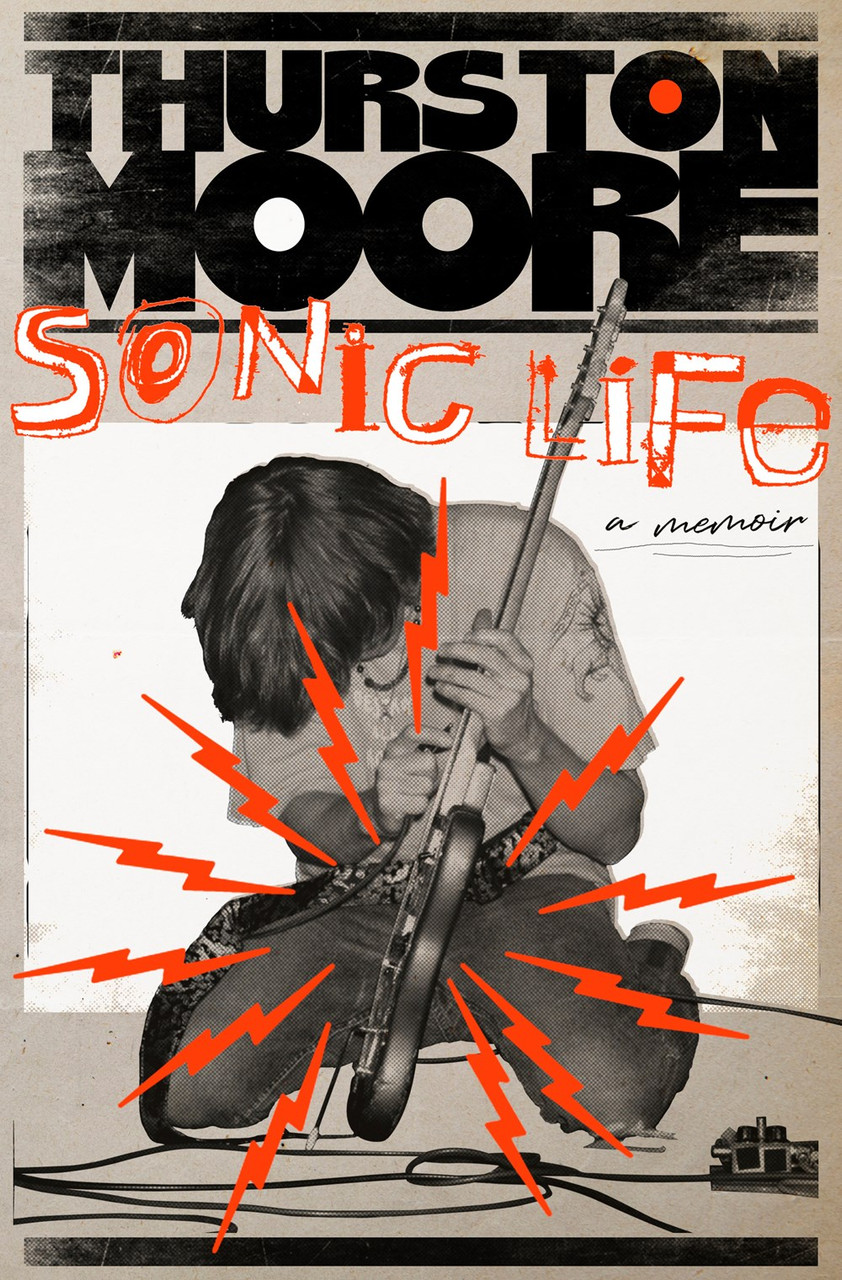

Sonic Youth’s modus for such caterwaul was feedback—sound projected and reflected into itself using cranked amps and guitar pickups—an endless, nameless, aural ouroboros from which a spectral force can be channeled that, in his memoir, Sonic Life, frontman Thurston Moore calls the “the psychedelic heavy metal no wave rainbow.”

Also Read

30 Overlooked 1994 Albums Turning 30

THE READ

For as twisted and berserko as this reads, Sonic Life is actually a coherent, digestible and visual experience that feels like it was written by a writer, and was. Moore was once a college music journalist at Western Connecticut State University, who quit the paper to create a fanzine—the OG Xerox, fold, staple and mail kind—full of writing too headstrong for school publications—the Richard Meltzer, Lester Bangs kind.

Sonic Life is also vastly entertaining, despite missing most of the content ultra-fans typically comb their favorite musician’s autobios for. There are no guitar secrets or songwriting tips to be mined, no Zen wisdoms to adopt. Few emotions are even expressed, and the 2011 split from life partner Kim Gordon gets nothing but a brief something about not wanting anyone to profit off of pain.

(This, while Kim’s 2015 Girl in a Band memoir brands Thurston “a serial liar,” and a “coward” who turned their lives into “another cliché of middle-aged relationship failure”.)

However, like all autobios worth their print stock, Sonic Life’s enthralling anecdotal content should easily earn it a spot on your bookshelf—especially its main course: a vivid and elaborate slideshow of Thurston’s coming of age in late-70s No Wave Manhattan. A more mythic artistic adolescence-slash-storybook New York success story couldn’t be imagined.

THE RISING

What better way of discovering one’s rock-star calling than fleeing suburban Connecticut in dad’s white Volkswagen Beetle, strapped in with your best friend and four packs of smokes, barreling down the Henry Hudson Parkway, onto the Westside Highway, and into the altered dimension of Ed Koch’s NYC to see bands you’ve gazed at in Creem, Hit Parader, and Rock Scene play live—

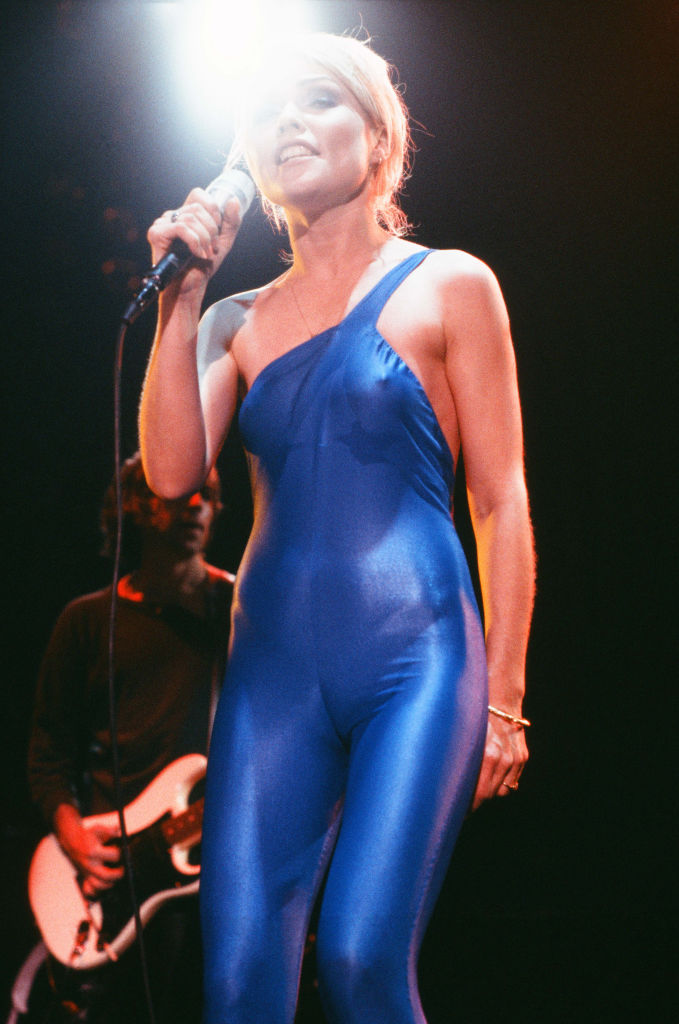

The Ramones, Television, Talking Heads, Patti Smith, New York Dolls, The Cramps, Siouxsie & the Banshees, Blondie, Richard Hell—at now-immortal venues—CBGB, Max’s Kansas City, Mudd Club—multiple nights per week, throughout your entire senior year.

Formative experiences for an impressionable suburban teen, ones that Sonic Life shares in great detail. Behold these and other timeless moments in time—

Thurston and pal’s first CBGB visit, sliding into the Patti Smith show on Joey Ramone’s tail, posing as his friends to gain entry, ending up elbow-to-elbow with William Burroughs. Later, entering the city the moment the ’77 Summer of Sam blackouts hit, reaching CBGB as all order disintegrates, finding owner Hilly Krystal out front with a candle, reversing course and racing out of the city, swerving around moon-eyed looters, watching as the Bronx becomes a bonfire.

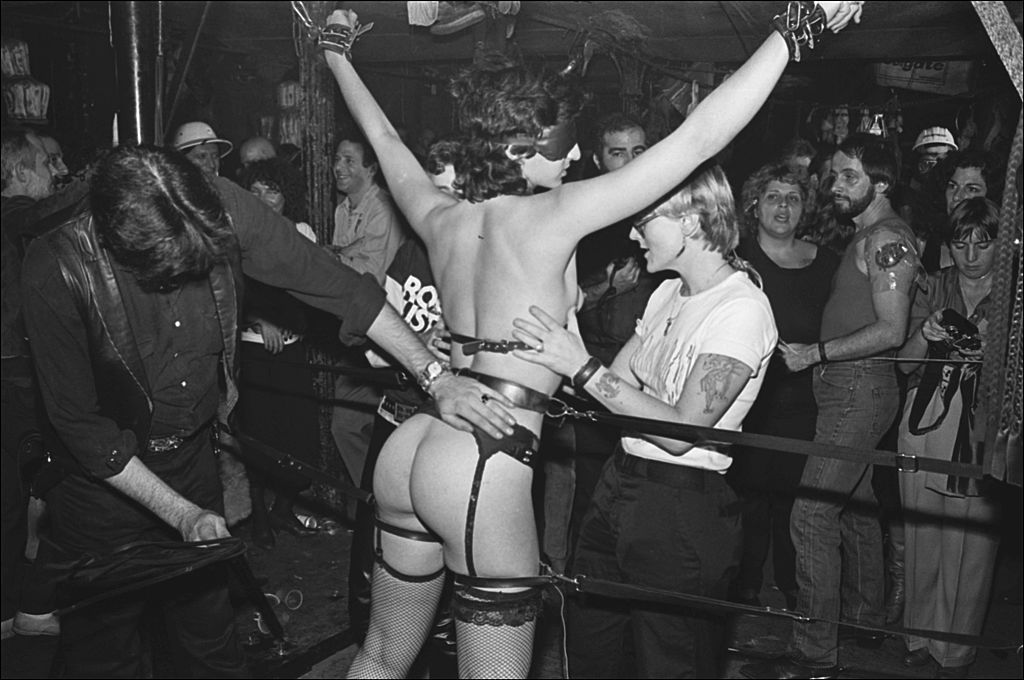

Returning to CBGBs a week later for the Dead Boys show, seeing lead Stiv Bators go mental, blowing his nose into bologna slices all night, rubbing them on the floor and eating them. Shoving a massive vibrator down his crusty leather slacks and working himself to orgasm while singing. Kicking in the head of the kick drum and crawling through it, vomiting. Tearing a random girl’s shirt in half, slathering her in peanut butter, and biting it off.

At Max’s Kansas City, mortified by Suicide’s nightmare proto-electro, watching singer Alan Vega in a bright old-lady wig grabbing fans by the hair, choking them out with his mic cord, spitting and screaming in their faces. Stomping chairs apart, throwing a drink in the eyes of a smiling girl from Long Island one table over, then smashing the glass and carving his chest open with it (sending Thurston and pal sprinting for the Volkswagen.)

Full-time college followed, though he and best pal’s big city abscondences continued, in force. Merely a bedroom guitarist to that point, the rabid simplicity of the punk being encountered gradually led Moore to consider musicianship, and after one semester, he dove headfirst into the amalgam of punk, new and no wave, hip-hop, graffiti, film and poetry manifesting in lower New York. Securing a near-condemned East Village apartment, the sonic life began.

The downtown art world was lawless, infected and immensely inspiring: drugs and sex and poverty and manic imagination equaling freedom for many reckless madcaps. For some artists, shows and life became blurred, performance identities bled into selves, resulting in the gradual immolation of birth names, pasts, and identities. On the bright side, some of modern man’s most imaginative music and artwork was being birthed downtown—available for appreciation to those who learned to walk the razor.

Thurston’s first band in the dregs was The Coachmen, a clean, comely 4-piece trafficking in palatable, Televisionesque new wave. Save for some half-ass spaz-outs, their ’79 “Failure to Thrive” EP was a toe in the pond artistically, but nonetheless, scene-worthy. Case in point, Moore tells of the Coachmen playing with something called Jean Michael Basquiat’s Homemade Jazz Band at a Xerox Art exposition of pieces by Basquiat and Kenny Scharf.

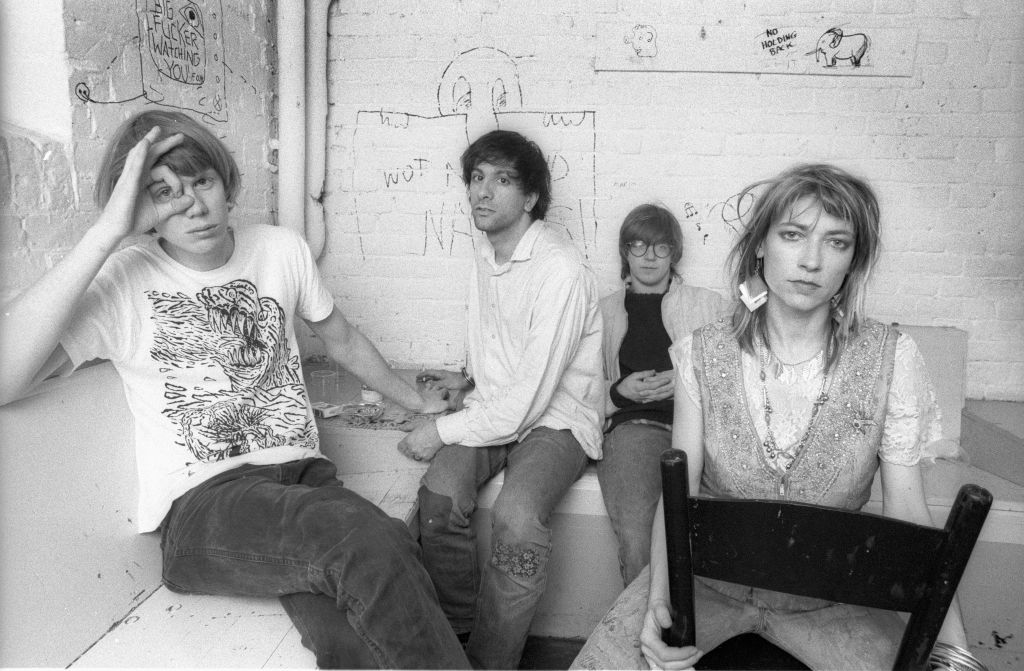

After about a year in the downtown trenches squeezed the last of drops of normalcy from his creative urge, Thurston met Kim, left the Coachmen, snatched Lee Renaldo from Glenn Branca’s Guitar Orchestra and local all-purpose drummer Bob Bert, and decreed Sonic Youth a thing—not as much a band as a sound-making art project, based around, as Moore writes, “three guitars melding, chasing, and spiraling into one another.”

THE RAGING

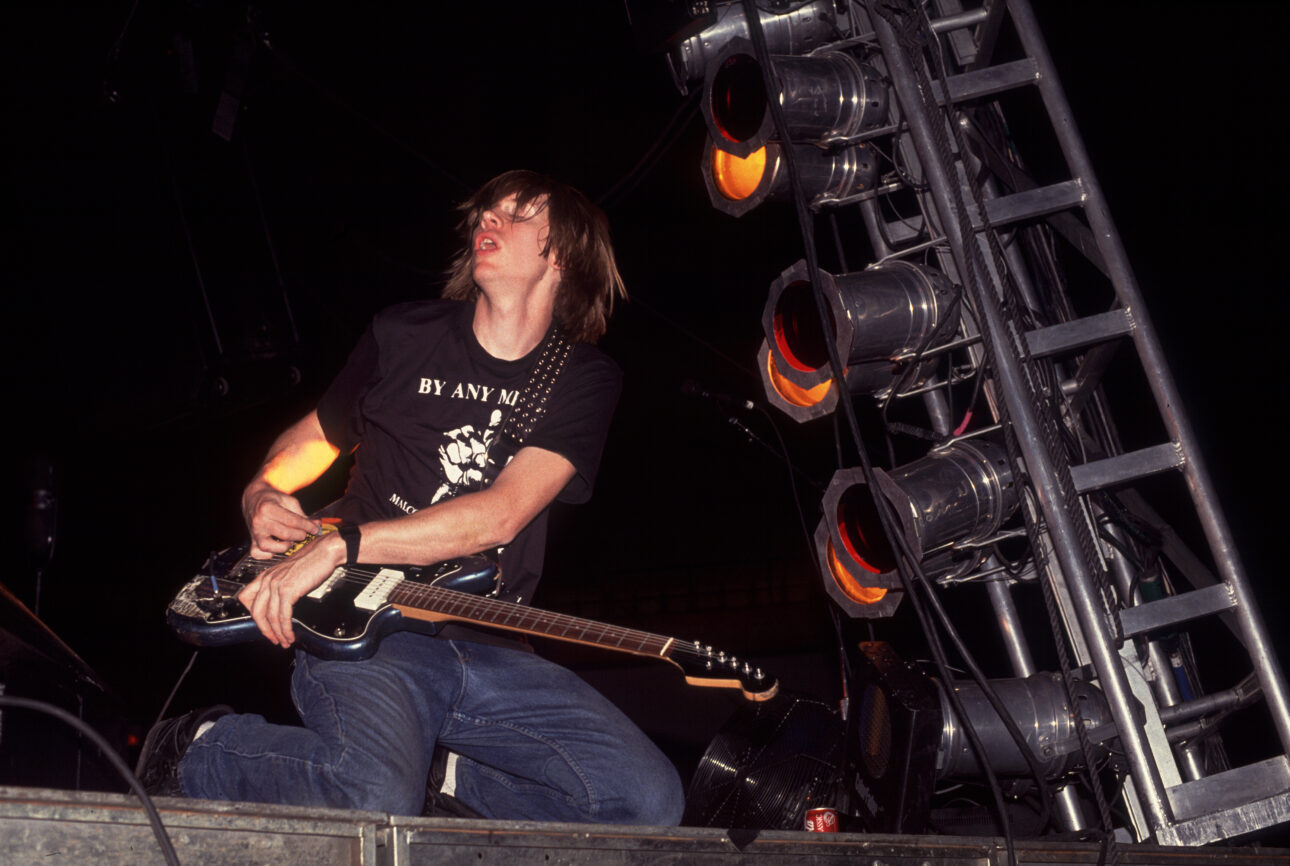

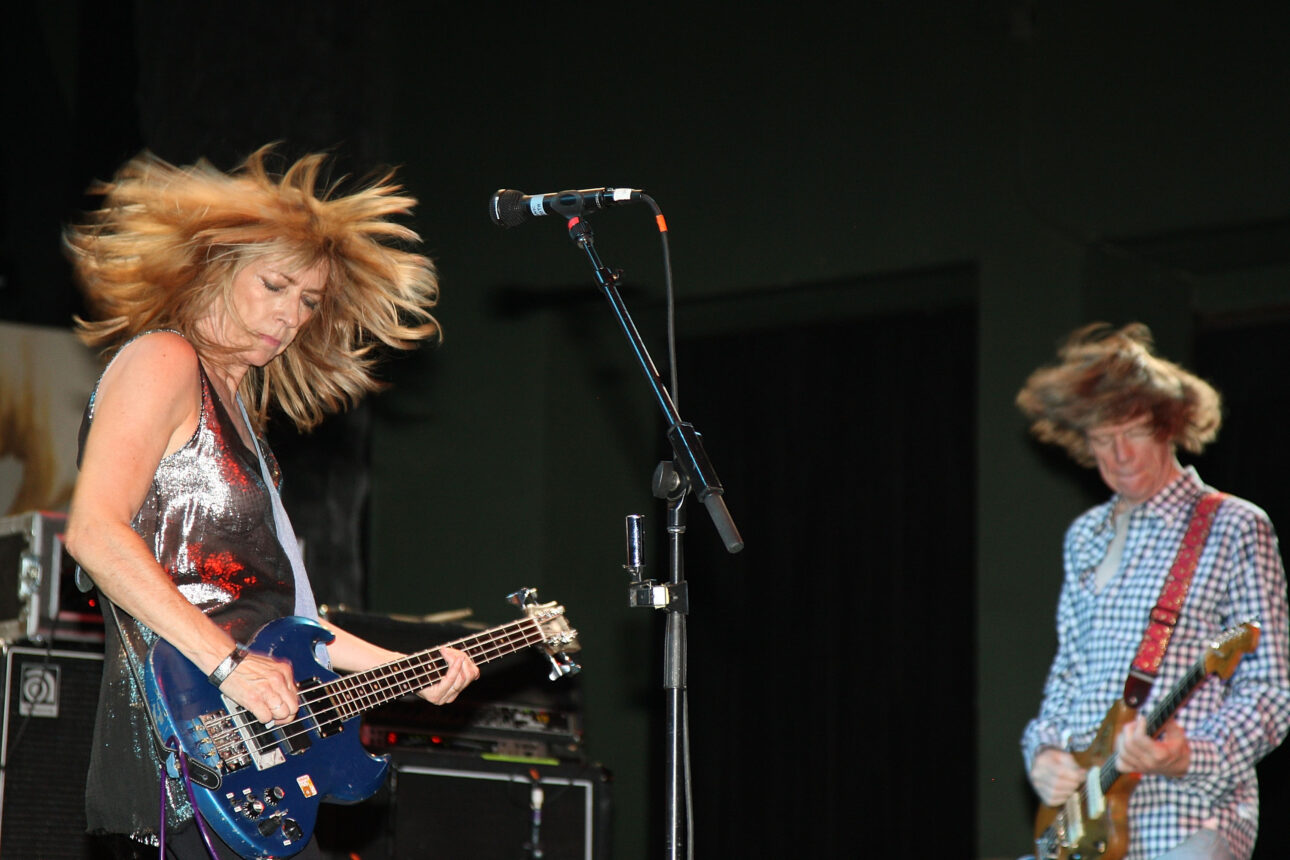

The early Youth approach was brutal and primordial. Guitars with drumsticks under their strings, pounded instead of played. Power drills raging through cranked amps. Basses hanging from ropes, being beaten with mallets, generating the gargantuan thrum of infinite Buddhist monks in mid-chant. What Moore calls “extended noise-paintings” were the result: songs less about their chords, melodies and arrangements than the roaring fjords of sonic babel that colored them.

Forever-drummer Steve Shelley’s arrival in mid-’85 saw more songs being written premised upon the singular voices of altered and damaged instruments they owned. Due to the approach, each specific guitar became irreplaceable, such that if any were broken or lost, songs that involved them simply couldn’t be played—not using entirely different guitars, or even different copies of the same guitar. As a result, Thurston and Lee toured with 50+ guitars during the band’s prime.

An exhaustive career-gear database on the band’s website logs 157 guitars and 26 basses owned, many set to tunings so peculiar that once dialed in they were never again adjusted, and at shows they were used only during songs that involved those tunings (as retuning a standard guitar mid-show could take minutes, not to mention snap strings and dislodge parts due to extreme changes in guitar neck tension.)

In 1990, the band committed a cardinal sin by signing a major label deal for the Goo LP, but then, by charting singles without compromising chaos, flipped the ‘selling out’ thing on its head. Their major move opened the doors for bands like labelmates Nirvana to go pop but stay sloppy, and thus, the great grunge rush commenced. But we’ll pause the history lesson there and leave the rest for the Sonic Life reader.

Actually, never mind, let’s have some more anecdotes:

Early ‘80s, on smoke breaks as a dishwasher at a diner, Thurston always filling Keith Haring’s wheatpaste bucket with water for his graffiti runs. A pre-Def Jam Rick Rubin screaming spit in Thurston’s ear about his punk band Hose at a deafening East Village show. In ’94, Meeting Beck playing a leaf blower through a bass amp at an LA backyard folk fest. At fame’s peak, Thurston learning from Paul McCartney the Ramones were named after the name he checked into hotels with as a Beatle in the ‘60s, “Paul Ramon”. I mean, c’mon. That’s some cool shit.

THE REFERENCING

But that’s also not it. Much more than just a fly-on-the-stall anecdotal gold mine, Sonic Life is a punk, hardcore, no- and new wave Library of Alexandria: absolutely splitting its seams with the names of every obscure group and artist Thurston has subsisted on for 50-some years—and we’re not talking bands any rocker worth his salt should know already. We’re talking arcane bands, bizarre bands, bands that played live but never recorded, bands that recorded but never played live, bands that only played once, and bands that broke up before playing.

Thurston knows of bands named FOOT, Jbala Sufi, Nurse with Wound, The Dead C, Hair Police, 8 Eyed Spy, 16 Bitch Pile-Up, Crass, Ut, the Dils, the Screamers, the Offs, the Mutants, the Adverts, the Mumps, the Weirdos, the Nuns, the Feelies, Room Tone, Theoretical Girls, Crime, Bags, Circus Mort, Test Pattern, Pulsullama, Liquid Idiot, Double Leopards, the No-Neck Blues Band and Cul de Sac.

He’s heard and seen bands named The Fluks, A Band, U-Men, V-Effect, Y Pants, DC3, Save Republic, the Erasers, Dark Day, Don King, Panther Burns, Mo-Fungo, Necros, Chinese Puzzle, Rat at Rat R, Red Milk, the Arcardians, Body, Avant Squares, Borbetomagus, Discharge, The Young & the Useless, Nihilistics, Urban Waste, Trigger & the Thrill Kings, the Mob, Mon Ton Son and Rubber City Rebels.

Thurston is well aware of Psi Com, the Diagram Brothers, the Leaving Trains, The Ex, Biting Tongues, Ludus, God’s Gift, Math Bats, Agitpop, Squirrel Bait, Viv Akauldren, Appliances-SFB, Hell Cows, Happy Flowers, Stiff Legged Sheep, Bramble Grit, Live Skull, and the Head of David. He doesn’t neglect Yoko Ono-ish ‘sound poets’ like Kurt Schwitters, Henri Chopin, and Jaap Blonk.

He pinpoints the origins and genres of enigmatic bands—Massachusets punk acts Sunburned Hand of the Man, Moving Targets, Sorry, the Outpatients, Busted Statues, and Deep Wound. He shouts out Soho No Wave bands in bulk–the Gynecologists, Arsenal, Tone Death, and high-risk performance artist Boris Policeband, a man strapped with blaring police scanners and an electric violin, who ‘played’ everywhere he went, but never played a show.

Thurston performs deep-dives into the mega-niche. How about Japanese noise cassette artists? Of course there’s Masonna, Monde Bruits, Merzbow, Hijokaidan, Incapacants, Aube, C.C.C.C., Hanatarash, Keija Haino, MSBR, Gerogerigegege, and Violent Onsen Geisha, all whom true to their genre name, only release creations on tapes, specifically, the Type I kind, the first cassettes that existed, the age-old kind with ferrous-oxide tape material.

The above hundred-plus names were gathered only by breezing through the book after finishing it, scanning pages for groups of odd, short words separated by commas; it can be comfortably said that Sonic Life holds many more band references than these. While dropping absurd numbers of band names is typically seen as a douche move, trust, Thurston is not flexing on us. He’s in no dire need of cred. He once got bored and made a song out of Yoko Ono breathing, then toured with her performing it in museums across mountainous regions of Europe. Get off his dick.

Face it, after 40-some years spent in the rafters of rad, few humans could peel back the stratum of underground rock to such delicious degree as Thurston Moore. The man is no braggart, just a G.O.A.T. with a burning desire to share wild and dangerous art of all forms. Dig him or not, let it again be said: Sonic Life is the definitive compendium of the most-influential, barely-known bands of the 20th-into-21st Centuries. It even offers benefits to the fakers and haters, as reading it is an easy way to instantly scale up your underground cool.

Go on, try it. Flip through the pages, stop, lay a finger, and land on some fascinating band names. Memorize and drop a few around strangers during the random convos that occur as the roadies clear the openers at a concert, then watch as your knowledge earns you a free drink from an impressed guy, or sends his joint your way during the headliner’s set. See that? Mentioning Panther Burns, Necros, Discharge and Chinese Puzzle did you well, now you’re high. You’re welcome. Better try and find out who they are, in case next time you get asked if you can recommend an album.

To this end, keep some earbuds and a laptop or phone nearby while reading Sonic Life. Experiencing the music being discussed is always a must when exploring a musician’s autobio, but failing to do so during this one would be an actual damn shame—you’ll likely never hear of most of these bands again, and a surprising number of them have at least a little something on YouTube that can be streamed for free (For info on the rarer acts, and to locate exhaustive info on their vinyl, cassettes and discs, hit up Discogs.com, an absolute treasure trove of a music resale site.)

Even for readers none too keen on Sonic Youth (or at least not yet), Sonic Life makes the perfect rabbit hole for initiating a spelunk into the vast underground labyrinth of ‘80s and ‘90s American indie music and arts scenes. One can only imagine all the fanatical characters, beautiful lunatics, and virtuosic bastards—God’s most gifted and haphazard one-off’s—to be discovered by simply Googling a weird name or five mentioned in the book and following the resulting hyperlink trail into movies begging to be made.

Normies blow, and Thurston has corralled legions of these who-the-hell-are-they’s to open for Sonic Youth over the years—as the book calls them, “extreme and marginalized artists,” such as “free improvising tabletop noise experimenters”—many of whom, having released but one tape and never played live, suddenly found themselves facing thousands of Sonic Youth fans. Despite existing at the apex of cool, Moore aligns himself with such beginners to this day, labeling his career just an “ongoing apprenticeship in the aleatoric avant-garde”.

For a guy who lives to obliterate the cochlea, Thurston has also never been the madman many of his punk compatriots were. Onstage, back the hell up, he’s thrashing about senseless making sex faces. Offstage though, he’s never dug on heavy drugs or groupies, and is often dressed straight prep-ski (though we learn his early Youth uniform of button-ups and khakis was only the result of the Canal Jeans store offering dirt-cheap, starchy-clean clothes in the seconds bin.) He’s a massive, lifetime fan of the Carpenters, and these days talks about peace and equality nonstop. Hadean Manhattan didn’t fry him.

Sadly enough though, Sonic Life’s New York, the demiworld where crazed creatives could survive, will never happen again in this civilization. Class, cash, and condos have pilfered and transfigured the filthen place that spawned No Wave. 35-years ago, Thurston paid $110 monthly for a two bedroom East Village apartment. Two bedrooms in Soho, near the band’s first practice space, currently rent at $12,000. Sure, crime was rampant, quality of life was mangled. The Apple was rotten, there’s no romanticizing suffering. But how it pangs the heart that the creative’s New York, Sonic Youth’s New York, is gone forever.

Read SPIN’s interview with Thurston Moore about publishing his tome