After catching music producer Rick Rubin explaining his book The Creative Act: A Way of Being on a Joe Rogan podcast, a lifelong friend who works in finance and investment changed the name of his fantasy football team from a slang term for sizable mammary glands to “The Rick Rubins.”

I was perplexed, as while my friend is into both old school hip-hop and self-made business gurus, he doesn’t give half a smidgen about the modern Rubin realms of profound introspection, emotional quietude, and nebulous Eastern philosophies explored in the book.

So what exactly was it about Rick expounding on abstract creative methodologies that caused this Wall Street warrior to change his fantasy franchise name for the first time in 13 years? He himself couldn’t explain it — “I don’t know. He’s the man.”

One way to find out — review the book!

Also Read

Ladies and Gentlemen, Mr. Tommy Lee

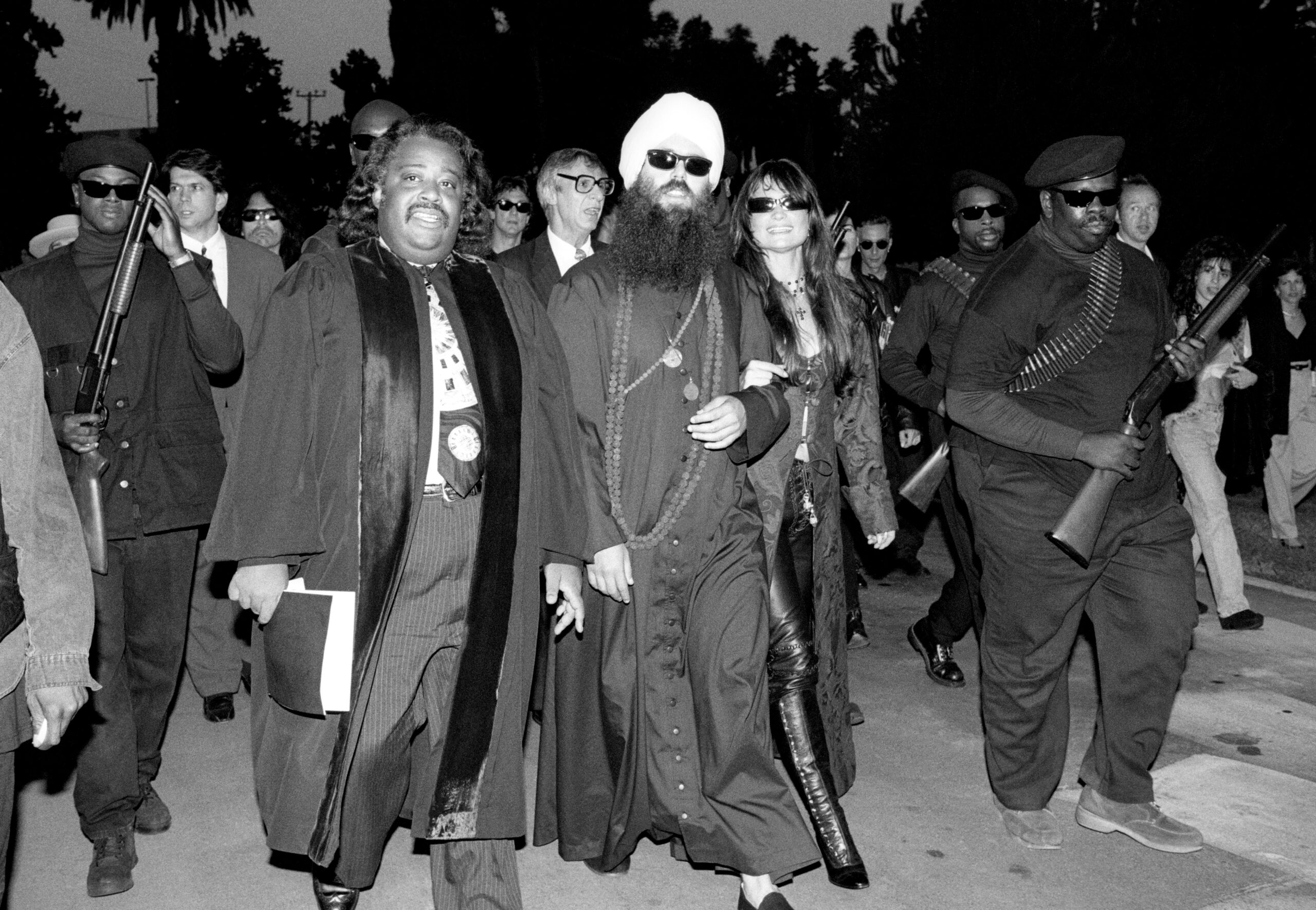

Frederick Jay Rubin is one of recorded music’s all-time most storied producers, who, after founding Def Jam from his cluttered NYU dorm room, began a stunning transformation from the shout-talking caveman throwing pies in the Beastie Boys’ “Fight for Your Right” video to the eternally still Zen-lord we gaze upon today.

[spin_quote_button quote=”My goal would be to be able to produce an artist, and have it be their best work, and never meet them or speak to them. That would be the ultimate version of it. I’ve not gotten there yet. I haven’t reached that level of skill yet.” attribution=”Rick Rubin, with a straight face, in Showtime’s Shangri-La documentary”]

Rick’s discography boasts not just cosmic sales numbers, but Grand Canyonesque genre width: albums from Danzig to Adele, Kanye to Poison, Johnny Cash to LL Cool J, Run D.M.C to Slayer, the Avett Brothers to the Geto Boys to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Sheryl Crow, the Mick Jagger, and the Jay-Z.

A deep mystique exists around his studio sessions. What really happens the moment the doors shut? Does he simply will the lights to dim, while cherubim with swirling neon eyes appear and speak his thoughts? The sensei’s book reveals a few secrets, though certainly none of such magnitude; in fact, few career anecdotes are included.

The Creative Act is far from a memoir. It’s something like a how-to, shaped like the man himself: a big, intriguing hunk of profundity. It reads precisely how his voice sounds: leveled, warm, and uniform. In fact, just imagining him reading it has a fantastically engaging effect. But if audiobooks are your thing, this one’s a gem: It’s narrated by Rubin himself.

As esoteric creative manuals go, Rick’s bears a slight resemblance to David Lynch’s Catching the Big Fish — plenty of mysticism, nature allegories, and meditational undercurrents. No career narratives or project-specific tales, however: a big let down for musicians and producers hungry for tricks of the trade.

Rubin does reference plenty of history’s great artists and works by name, but when discussing his collaborators he speaks solely in anonymities, providing vague insights on the methods and mindsets of “one of our generation’s best songwriters,” or, “the modern-era’s top pop star.”

Moments of The Creative Act approach Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, the atmospheric cleric’s card-deck of brief statements meant to be drawn from randomly and used as creative cues.

Rick’s recommendations for priming the mind to invent include: “Turn off the sound to watch a film … arrange stones by size or color … read the first word of each sentence in a short story.”

Suggested creative exercises also include beating a pillow full-force for five minutes straight (don’t give up!), then writing for five minutes, and to “receive” ideas by “non-thought,” humming melodies or dictating ideas to your phone while your active mind is occupied doing the dishes, walking outside, or showering.

Buddhist koans and paradoxical riddles meant to strategically disarm the logical mind are provided for rumination, as are fortune-cookie wisdoms resembling Old Testament proverbs: “The lottery winner isn’t ultimately happy after the sudden change of luck … The home built hastily rarely survives the first storm.”

The book’s first half is also packed with brief commands (“Remain open to the unknown … Break Habits … Look for differences … Notice connections … Submerge yourself … Listen with the whole body … Be aware of assumptions”), each stuffed randomly between longer, more involved sentences. Many feel disconnected from the sentences that sandwich them, and offer little instant utility, which may…be the point?

It appears that as chapters are plowed, seeds are being scattered, only to yield harvest if given time to sprout. But don’t dig for meaning. Upturning the soil in search of new life will only prevent it from growing. Lessons must be given time to take root and unfold like flowers, not forcefully pulled apart. So says Rick, without saying it.

Waiting for knowledge to appear from writings about waiting for knowledge to appear can be monumentally frustrating, but there’s no other way to “get it.” It’s a bitch, but those are the psyche’s rules, not his.

Some advice for beginner deep-thinkers: Set your creative aims then browse the book throughout the day, perhaps 15 pages per sitting. Between reads, let thoughts that “sound regular” float past, until eventually, a thought with a different voice occurs. Write that one down, and repeat. They will come eventually, if you keep picking the book up, which can actually be quite a task.

No passages of true literary vibrancy await; no paragraphs provide a ride. Just as the contemporary Rick rarely yells or waves, The Creative Act rarely becomes animated. In fact, it becomes so gray that the reader risks cruising through chapters of haze without taking anything in. Hearing or watching the man himself communicate is transfixing, but typeface has no equivalent aesthetic aura.

The Creative Act is also very liberally spaced, making it even easier to roll through without stopping. When you add up the book’s ample blankness — white space galore! — more than a quarter of the tome has nothing on it, presumably to “keep the mind clear.” This approach is common in Buddhist literature like Shunryu Suzuki’s classic Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, which features two blank pages at its center — blank, save for one printed fly.

(Master Suzuki’s lesson: Keep that mind slow and still, or you’ll scare the insights away. Rubin’s blanks however, contain no flies.)

Given its lack of immediacy, some may call The Creative Act useless, as some bands have dared call Rubin’s notoriously passive approach to production. Dissatisfied clients like Muse and Slipknot, among other major players, have spoken of being left to record with a lowly engineer for a week, before Rick returns for a listen, nods, and leaves without any real interaction.

The irony is, given the The Creative Act’s methodology, one could interpret this series of events as the ultimate compliment, an entirely telepathic affirmation of course. For the rare few dialed directly into the cryptic realm of Rick, the absence of critique and the presence of silence may communicate:

“You are doing so well without me, I won’t let you see my face, lest the hint of an expression alter the arc of your art by a 10th of a degree.”

“These demos are amazing — what idiot directs orchids to unfold? Your talent is blinding — what fool tells the sun how to rise, or congratulate it when it does?

“I’ll be back when the universe whispers to me.”

For less ethereally minded musicians, however, who have undoubtedly dropped serious coin to attach the Rubin name to their brand, studio ghosting and non-participation could understandably be read as insulting. A hands-off approach is no breach of agreement, however, as “produced by” is the most indistinct credit in music.

In the literary world, “written with” is equally vague. The Creative Act… was written with Neil Strauss (author of best-sellers like The Game and Emergency: This Book Will Save Your Life), perhaps the celeb favorite for autobio help-outs. “Written with,” however, doesn’t always infer equal involvement.

So who really does what when Neil sidles up? Strauss is said to have full-on ghostwritten Jenna Jameson’s How to Make Love Like a Porn Star and Motley Cruë’s The Dirt. Both books feature his name on their front cover and spine (as do his works with Marilyn Manson and the Jonas Brothers), but curiously, The Creative Act … keeps Neil constrained to the bottom of its cover page.

The Takeaway

The Creative Act can be a rich, enveloping read for those out there who have previously tapped the wellsprings of creativity using clear-mindedness — its exercises can serve as a great new set of directions to a familiar vacation spot within. But for those not ready for the intellectual slow-go of allowing meanings to present themselves — and many of us never will be — its erudite words may go in one eye and right out the other.

By any measure, big props to Rick, as attempting to describe the indescribable by not describing it is very thin ice for any writer to tread without having their contract canceled upon submission of the first draft. (To that end, props as well to Penguin Random House for trusting the man — you truly are random!) It’s an authorship model that takes genius to attempt…or…was it not even Rick who attempted it?

Let’s get kooky here for a minute. Is The Creative Act: A Way of Being really just the result of life’s timeless indescribable energy longing to describe itself, and in an attempt to do so, possessing Rick Rubin to expertly describe It using a writing method which allows It to be revealed to our world while still remaining hidden?

Is this book simply the result of It, God, Allah, Buddah, the Source (as Rick calls it), She, They, Fido, or any other amorphous capitalized term for the Almighty, holding two mirrors up face to face? One can’t say, as the answer lies in the vertiginous dead-center of those two mirrors, in a far-off yet ever-present vortex known as infinity.

Time to go beat that pillow.