Not playing by conventions has been a part of Sonic Youth vocalist/guitarist Thurston Moore’s creative playbook for more than 40 years, and it’s a sensibility channeled in his long-awaited memoir, Sonic Life, which was released late last month.

The group emerged from the vibrant New York underground rock scene of the early 1980s and went on to blaze a trail of independence and innovation throughout the rock world, even after signing to major label Geffen Records in 1990. Its influence on bands such as Nirvana, Dinosaur Jr., Pavement, and My Bloody Valentine played a major role in the alternative explosion of the 1990s, and Sonic Youth was still riding a hot streak at the time of its sudden 2011 split, a decision necessitated by Moore’s divorce from group member Kim Gordon after 27 years of marriage.

This messy breakup is only mentioned briefly in Sonic Life, a 77-chapter, nearly 500-page memoir in the works since 2017. Instead, it focuses on Moore’s connection with music, opening with his introduction to rock’n’roll after hearing “Louie Louie” on a seven-inch single brought home by his brother. Throughout Sonic Life, Moore, 65, primarily focuses on his evolution from music fan to indie rock pioneer, including encounters with Joey Ramone, Iggy Pop, and Kurt Cobain, and an arrest after a high-speed chase in his rural Connecticut hometown.

Rather than dwelling on Sonic Youth’s muted farewell, the book concludes with the liner notes from the band’s final album, 2009’s The Eternal. “I wanted the recording of The Eternal to be the cherry on top,” Moore tells SPIN by Zoom from his West London home of his decision to end the memoir this way. “Poetically, it made sense.”

Also Read

30 Overlooked 1994 Albums Turning 30

The idea for Sonic Life was suggested by Moore’s wife, book editor Eva Prinz, whom he married in 2020. “I didn’t know if I should go further into moving to London, but I wanted it to end with Sonic Youth,” he explains. “I didn’t want it to be some kind of weepy thing. And Eva said, ‘Your last album was called The Eternal, so why don’t you just have that be the last two words? I was like, ‘Great idea. Glad you thought of it’. That gave me an ending.”

Moore worked on Sonic Life while keeping busy with his own music, including four solo albums in the past six years and appearances on obscure compilations such as Cuts Up Cuts Out, as well as one-off larks such as recently covering Lou Reed’s “Satellite of Love” with Snail Mail. A planned U.S. tour in support of the book was canceled while Moore is managing atrial fibrillation, a condition which can cause an irregular heartbeat.

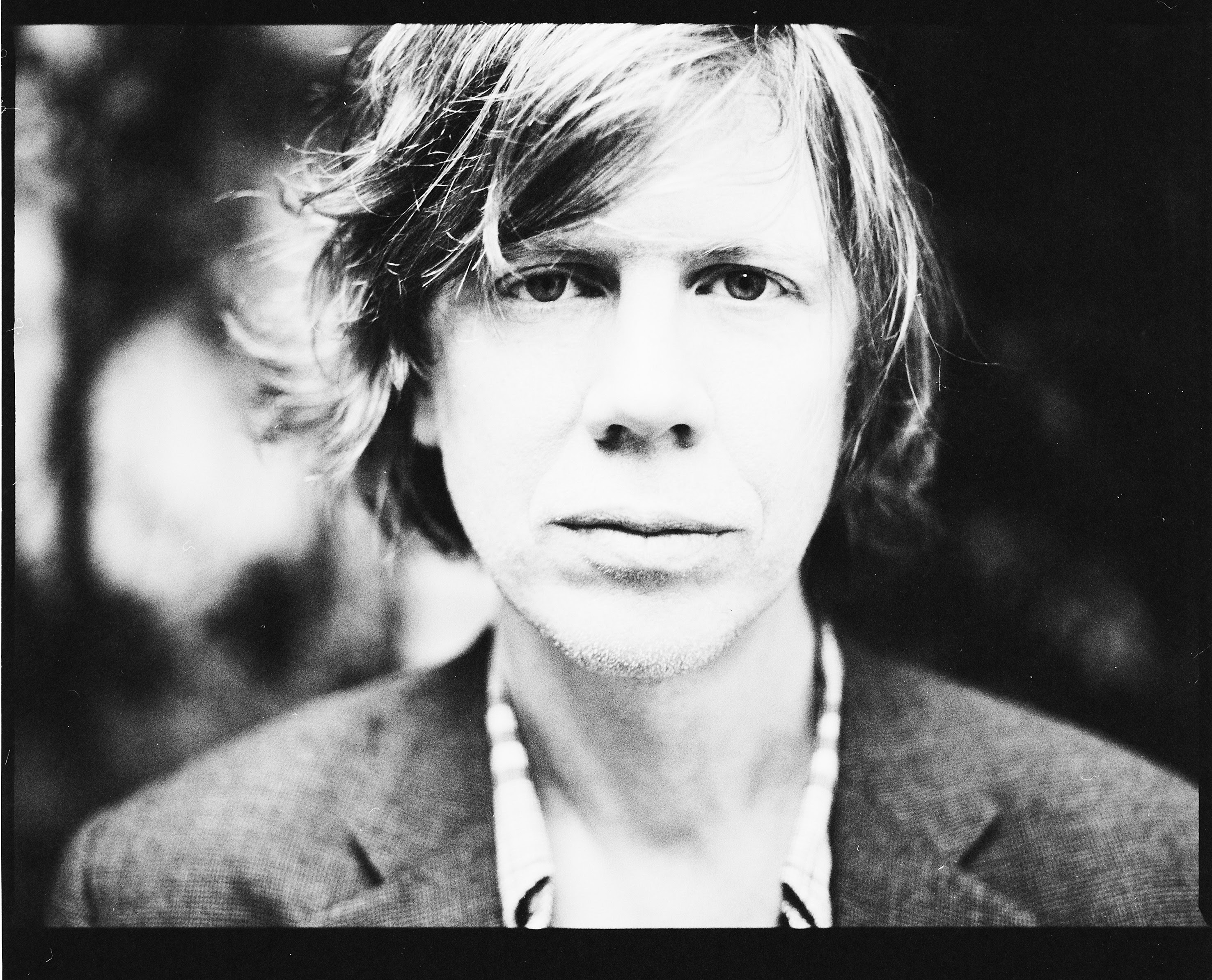

“This year, it has started getting more pronounced, to the point where I felt extremely weak and could sometimes hardly walk around the block,” Moore says, adding that his London-based doctors have “pretty high” confidence he will recover. Below, the artist explained the genesis of Sonic Life, the romanticization of Sonic Youth’s heyday, and what the band might have sounded like if it traded its guitars for chainsaws.

SPIN: Why was the time right for you to write your memoir?

Thurston Moore: I wanted to write about the history of Sonic Youth through my prism at some point. Our band has been out of business for a number of years, so I felt like I could write it anytime. I wanted to engage with writing a long-form book where I essayed about music. I originally just wanted to write about the signifiers and the documents that informed and intrigued not only myself but the micro-community that I was involved with.

At first, [Sonic Life] was going to be this open, experimental take. However, I realized that I wanted to have a chronology that showed the development of a band that existed as long as we did. I think any band that has existed for more than five years is an anomaly anyway. So when you get to a tenure point, it’s kind of remarkable. When you get to 20-30 years, it’s even more remarkable. Sonic Youth certainly got into this legacy status. But, there are many bands that remain deep underground bands that have been together forever. Like Smegma or Los Angeles Free Music Society.

So, why now? A lot of this has to do with being sort of old enough that I felt like I could have a voice that is quite removed from the voice I would have had in the ‘80s and ‘90s. The voice is retrospective, but it’s written in the voice of a 65-year-old writing about a 20-year-old. So when I write about my relationships with band members like Kim or Steve [Shelley] or Bob [Bert], they’re very young. There’s not much self-analysis going on in the book because I’m not interested in getting involved with that. I find that to be slightly egotistical and boorish. I’m more interested in writing about Patti Smith’s Seventh Heaven poetry book in 1974 and how significant it was to so many people who would come together and meet each other in these clubhouses, like CBGB’s or Max’s Kansas City. I wanted it to be about the joy of being in a band, even though I go to places that I need to write about, such as my father dying. These kinds of things are necessary for transitions.

Why do you think there is a fascination with the period when Sonic Youth rose to prominence?

For many, it was some type of ultimate period where there were music scenes that were regional, and very defined as such by the Midwest scene, the L.A. scene, the San Francisco scene, the Seattle scene, and of course, the New York scene. You don’t see that collective energy so much anymore. Certainly our lives are more open to the internet, where it doesn’t necessitate where you come from. To me, this is what spurs a lot of interest in what that lifestyle was like before this cataclysmic change we’ve all had, where we’re all interconnected.

What do you like or dislike about music memoirs?

I’m surprised by how many music memoirs I’ve read by contemporaries that deal so much with heroin usage. I always knew it was around my world, but it was like, ‘my God — was everybody doing heroin except for me?’ [Sonic Youth members] Lee [Ranaldo] and Steve and Kim, we were so conservative. It was a paradox because we were always the straightest batons at Lollapalooza, but we were playing the most bent-out-of-shape music. It was like, the more strung out a band was, the more straight ahead they were with their rock and roll. Consequently, bands like that are more popular because they’re accessible. We were never entirely accessible. That’s the kind of music we were making, but we were certainly clean.

Sonic Youth always kept fans on their toes by constantly evolving. What is it like looking back on every period of the band’s growth?

In some ways, it was always purposeful to want to do something surprising, or at least something as a reaction to the previous recordings. I went to see [novelist] Colson Whitehead do a reading here in London. As a writer, he knew he could still write as a reaction to what he’d written before. I related to that. It was certainly the group thought of Sonic Youth. We always wanted to not only do something different but to have it be even more exemplary musically. In some ways, that was liberating. During the ‘90s, it allowed us to coexist by putting out song-based records, as well as experimental, instrumental records. By the time we did The Eternal in 2009, I felt that was as strong as a statement that we could make at that point. Anything beyond that would maybe start to become a bit of wheels spinning.

Did you notice anything slowing creatively around that time?

I started seeing that happening as a touring band in the last couple of years of our existence. We had become decoded to some degree. I also noticed that our audiences were becoming more like, ‘we’ve heard at all,’ and ‘not only have we heard it all but we’re hearing other bands do it with a bit more refinery.’

What do you think Sonic Youth’s legacy is and will be?

We never made any conscious decision to change the game. It was very intuitive, especially after The Eternal. I felt maybe we should take a break, not realizing that we are going to be taking a break as soon as the word got out about Kim and I separating [in 2011]. The band would not be functional. We didn’t know what that would entail, or what was going to go down with that. So it was never really thought of as ‘the last record.‘ I used to tell people if we do another record, we’re just going to compose it with chainsaws and pianos. When I’d say that, Ranaldo would look at me and be like, ‘I’m down, let’s do that.’ I always liked the idea of Sonic Youth sort of existing as such, even though we became inactive in 2014.