It’s difficult to know where to begin in approaching a film like Joel Silberg’s 1984 project Breakin’, which proudly conveyed its worthiness in our collective nostalgic zeitgeist, through home entertainment releases, with the proclamation: “It’s the classic film that started it all.” A 2003 DVD release went so far as to boldly assert it as the film “Where Breakin’ Was Born,” therefore answering the question to what “it” was being started.

Such a statement is an audacious fallacy, considering that breakdancing, one of the tenets of hip-hop culture, was already in full swing by the time Silberg’s film went into production, capitalizing on themes and communities portrayed in earlier titles like Wild Style (1983). The film actually purloins its main talents from the 1983 documentary Breakin’ ’n’ Enterin’ from director Topper Carew.

Also Read

Death Be Not Proud

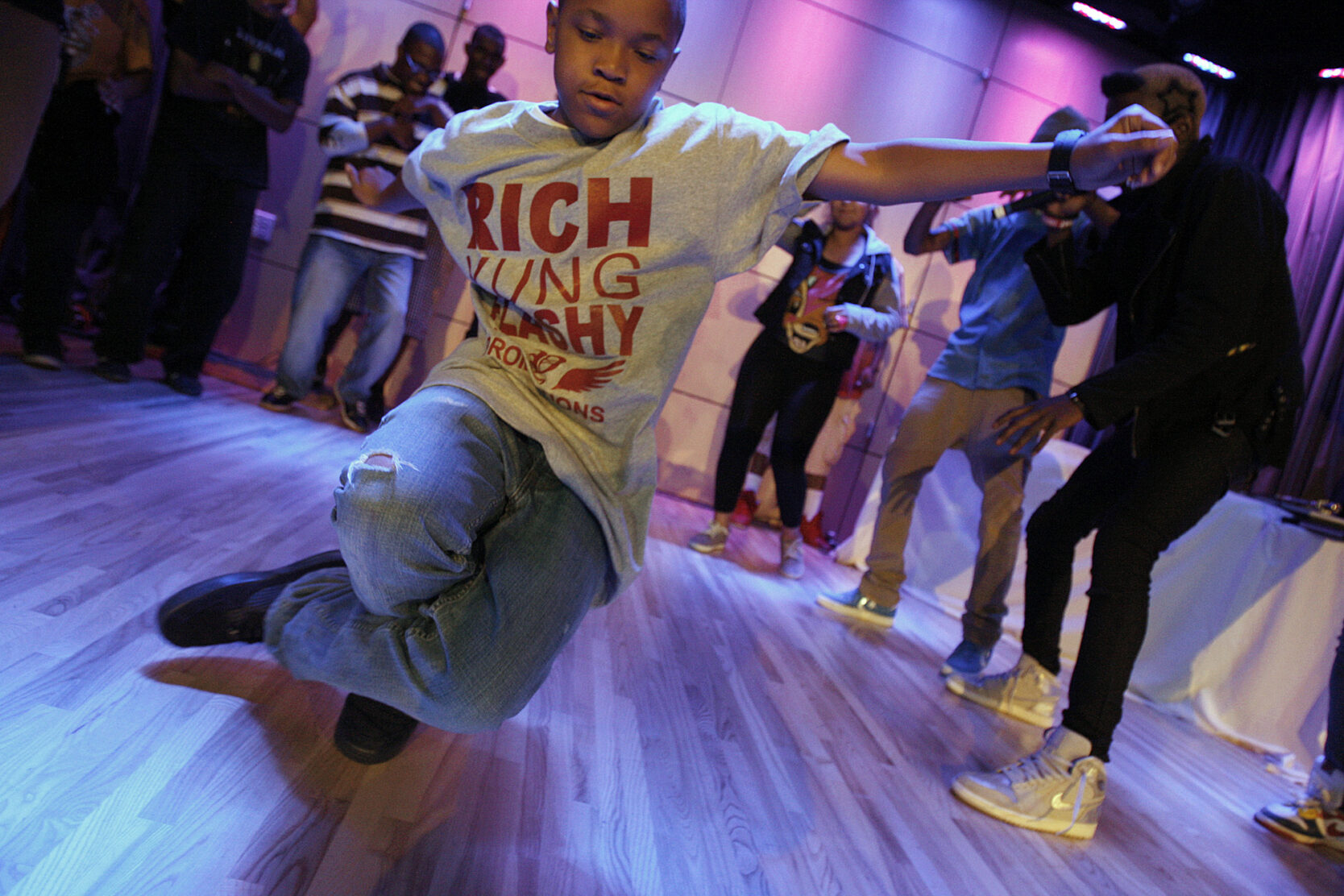

For those who remember it, Breakin’ debatably remains an enjoyable if cheesy film, an odd bird intended for white audiences’ sensibilities, but featuring a trio of Black and Latino supporting characters defying the limitations imposed upon them. Now, on the verge of its 40th anniversary, it is one of countless films whose recuperation might be questionable to some but imperative to others. Is it one of the most undervalued dance movies of the 1980s?

The movie is about a dancing ingénue named Kelly, nicknamed “Special K,” played by Lucinda Dickey, who has run up against a kind of glass ceiling with her smarmy dance instructor Franco, whose pretensions barely conceal the sexual designs he has for his prized student. Thanks to her dance cohort, Adam (Phineas Newborn III), who sees something in Kelly both she and the audience does not, she is introduced to his street dancer friends Ozone (Adolfo Quiñones) and Turbo (Michael Chambers) in Venice Beach, the former taking an immediate liking to her. Kelly attempts to bring them into her elitist domain, but Franco isn’t appreciative of what he refers to as their “low-class” talents. When Kelly attends a club where Ozone and Turbo engage in a dance battle with rival dance crew Electro Rock, Adam convinces his friends to train Kelly to breakdance so they can defeat their rivals.

This eventually culminates in the trio entering a traditional dance competition. Franco attempts to sabotage their entry, but, as expected, they prevail and become an immediate success. Ironically, the film’s direct sequel showcases how Kelly was able to use the experience to advance her professional career, returning to assist her old friends who have wound up teaching dance lessons to kids at a Los Angeles community center in a swiftly gentrifying neighborhood.

The easiest way to confront the legacy of Breakin’, and its arguable cinematic and cultural contributions, is by defining its indubitably disagreeable elements as, for all intents and purposes, an exploitation film. Although it can technically be categorized as a cult classic with its own set of devotees, Silberg is a director whose works are far beyond the pale of camp, a distinction earned when a film’s desired ambitions or intentions may have failed, instead creating an unintentional gloriousness (which could just as well be called “accidental art”). Silberg was clearly capitalizing on a trend without fully understanding either a narrative aim or a comprehensive perspective of the community he was plundering. There are some unexpectedly powerful pieces of representation thanks to the talents of supporting cast members (specifically Adolfo “Shabba Doo” Quiñonesand Michael “Boogaloo Shrimp” Chambers), but they’re sandwiched into a woefully shoddy narrative penned by Charles Parker, Allen DeBevoise, and Gerald Scaife (none of whom would write another screenplay). If there was any initial ambiguity as to Silberg’s intentions, who did not return to direct the sequel, Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, which was released the same year, one only has to look further into his résumé and experience his complete trilogy of musically inclined exploitation titles, each a poor attempt at highlighting the creative aptitude of communities he clearly knew nothing about. In comparison to 1985’s formidably mediocre Rappin’ and 1990’s sleazy Lambada (which brought back Quiñones to bolster the inadequacies of the film’s leads), Breakin’ may seem masterful at certain times.

At its core, Breakin’ plays like a template for various dance movie romances that would eventually become more culturally iconic. While Silberg flirts with suggesting an interracial romance between Dickey and Quiñones, their attraction seems absolutely fetal when compared to something with a similar dynamic regarding a worldly, masterful male dancer who trains and then falls for a younger woman in Dirty Dancing (1987), notably a film set in a much more conservative period, in a homogenous, all-white community. Something like 2001’s Save the Last Dance would finally engage in energies something like Breakin’ was gunshy about in 1984, though still prizing the aspect of exploring Black culture through the prism and experiences of a young white woman, who is meant to be the safe passageway for the white audiences its makers infer cinema is automatically intended for.

Lucinda Dickey, trained as a dancer, remains the film’s most tiresome element, a blank slate as Kelly, upon whom the film’s dramatic catalysts are harpooned. In the even less competent sequel, where she returns from abroad to help Ozone and Turbo save the demolishing of a community center through a dance event, the unstated romantic awkwardness at least allows for Kelly’s whiteness to be confronted by some of Ozone’s other female admirers (including Quiñones’ wife at the time, a young Lela Rochon). Dickey, whose third release of 1984 was the much maligned Ninja III: The Domination (which includes an infamous sex scene involving tomato juice), notably didn’t pursue an acting career into the 1990s.

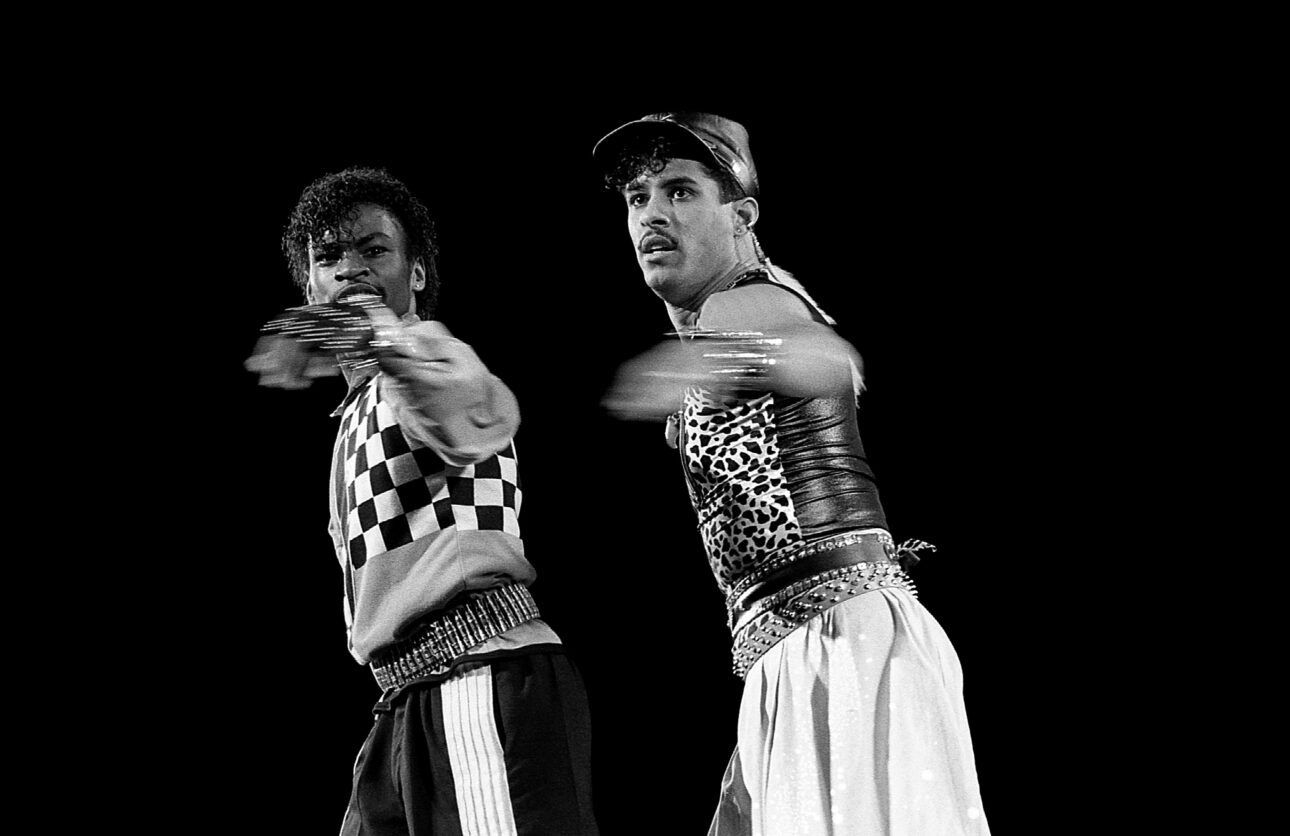

And while familiar faces like Christopher McDonald and Ice-T (who would also collaborate on Rappin’) appear on the sidelines, the real star of the show is Adolofo Quiñones, credited as one of the originators of hip-hop dancing, in particular “locking,” as he was part of the the Original Lockers, a dance group founded by Toni Basil and Don Campbell (the move was initially called the “Campbellock”), who specialized in street dance. Quiñones was also an original member on Soul Train and first appeared in noted disco films like Disco Fever (1978) and Xanadu (1980). However, his role as Ozone remains his most widely-known characterization, and the best moments of Breakin’ are whenever Ozone and Turbo are engaged in their own dance numbers. One of these moments finds Michael Chambers imitating Fred Astaire while he cleans a convenience store.

But arguably the most interesting element of Breakin’ is one of its least talked-about characters, a young man named Adam, played by Phineas Newborn III. Adam plays Kelly’s friend who squirrels her away from the toxicity of their impetuous dance instructor into the welcoming arms of Ozone and Turbo (though it should be noted the latter is quite suspicious of Kelly when she first comes around asking ignorant questions). What’s notable is how unabashedly queer Adam is presented, allowing for the veritable gap between not just the film’s white and Black characters, but also the bridge between cultures, sensibilities, and art forms.

Thomas F. DeFrantz, Professor in the Performance Studies Theatre Department at Northwestern, has written extensively on Black Performance Theory, having published several significant essays on hip-hop, categorizing Silver’s title as part of a movement he coined “breaksploitation” films, citing specifically how this film provided the direct template for the Step Up films over two decades later. In speaking with DeFrantz, we discussed at length the subconscious utilization of Adam in Breakin’ because he represents the necessary stepping point between parallel cultures as a Black queer character existing in various intersections. “You need queer femmes’ space and energy,” he says. “You need disco to connect punk and hip-hop to pop culture and mass media.”

Likening a character like Adam to the legacy of Ru Paul allows Breakin’ to remain part of an ongoing cultural conversation.

When asked if Breakin’ is one of the most important hip-hop films of the 1980s, standing out amongst a cycle of similar films from the same period, DeFrantz suggestively agrees in first discussing why it is not. In short, the films it stands on the shoulders of are much better, if ultimately rough around the edges. But they don’t have the same cultural reach since Silberg’s entry was a Hollywood film. So, because it is a Hollywood film, “it follows all the tropes of everything before it and everything that comes after it.” Arguably, the impact of Breakin’ seems greater when included with the films it overshadows (like Stan Lathan’s Cannes-premiered Beat Street from the same year), together orchestrating the organization of shifting and eventually coalescing cultures.

If Breakin’ doesn’t quite deserve a grand recuperation as one of the best hip-hop films of the ‘80s, at least not without significant caveats to defend its shortcomings, is it, perhaps, the most undervalued dance film of the 1980s? DeFrantz, who has explored how this cycle of films, depicting a “new” cultural phenomenon (actually 10 years old by 1984) exemplify an “insider-outsider” sensibility, in that its subjects simply wouldn’t have had the necessary access to control the production of their own image in this period, remains evasive about qualifying the film in any distinctive way. “I don’t necessarily need it to be something else that it isn’t,” he says.

A more diplomatic approach might be to recognize how Breakin’ is unintentionally one of the most undervalued 1980s films that showcases the importance and necessity of Black queer culture and all those who are forced to walk (or dance) between worlds which cast them into the shadows of a periphery. And the power of retrospective and recuperation allows us to recognize their invaluable cultural contributions. In the lingo of the film’s tagline, you’ve got to “Break it to make it!”