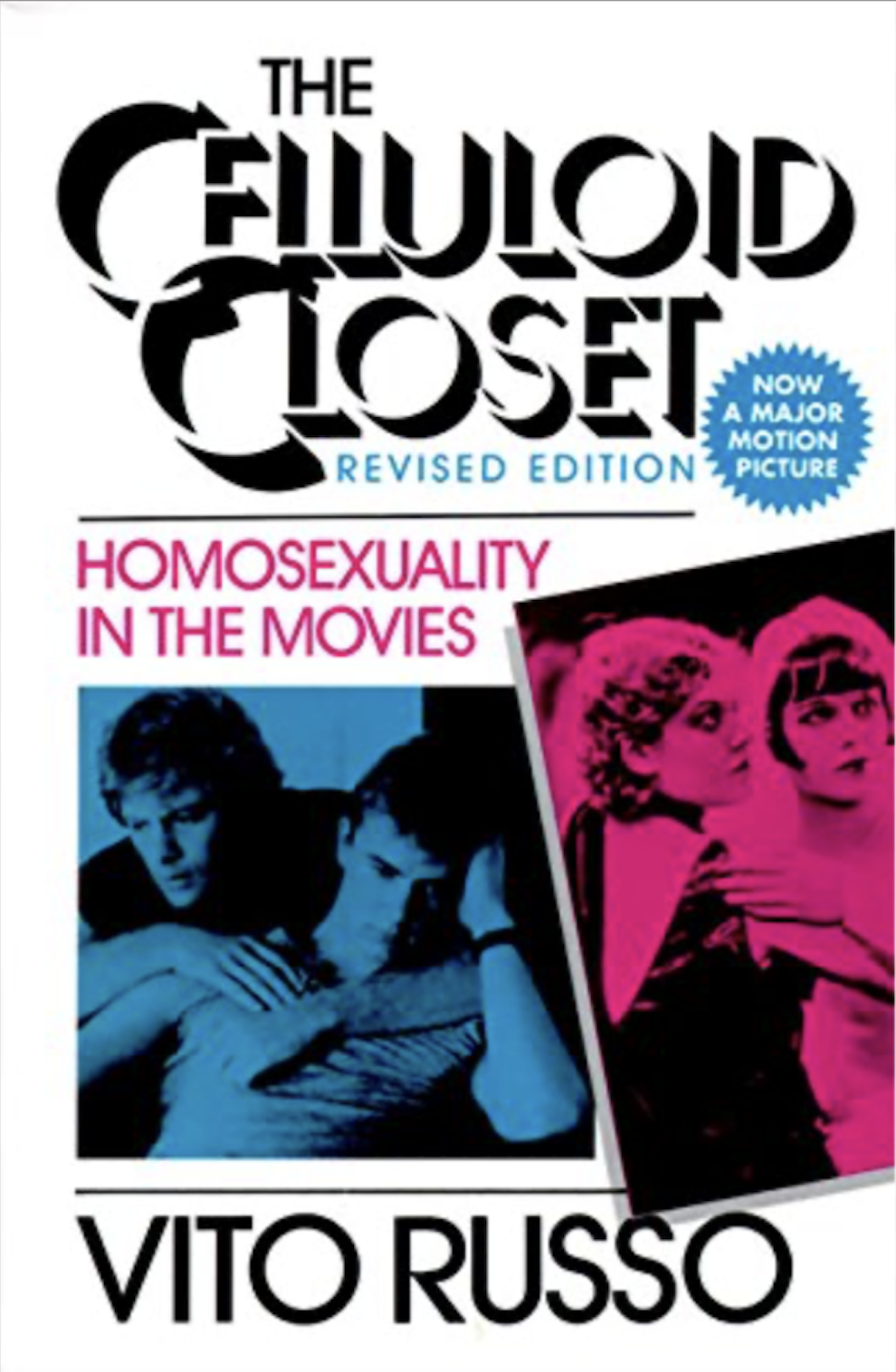

“Hollywood is yesterday, forever catching up tomorrow with what’s happening today,” wrote Vito Russo, the activist and film historian who gave us the first comprehensive audit of homosexuality in cinema with the 1981 publication The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies.

But even if films are automatic time capsules reflecting cultural standards and norms, the cinematic products of Hollywood assist in maintaining adherence to the social norms of yesterday. A seminal first-wave queer theory text, Russo’s magnum opus detailed the dark odyssey of repression, suppression, exploitation, and erasure that shaped the representation of queerness in Hollywood and beyond, where the art of the moving picture has been consistently guarded by puritanical patriarchies and heteronormative conditioning. But Russo’s first edition arrived on the eve of a dark era with the onset of the AIDS crisis, devastating an entire generation of gay men, the ripple effects of which saw its surviving artists consumed with and defined by their relationship to AIDS.

Prominent queer narratives from the late 1980s to the 1990s—which, to younger generations reared in an era with HIV prophylaxis and a newly liberated sex-positive culture, now play like horrific sci-fi sagas from a parallel universe—were forced to directly contend with the dismal reality of the disease. How unfortunate it is we were not able to utilize Russo as a guide in real-time through the onslaught of trailblazing films such as Longtime Companion (1989), Common Threads (1989), And the Band Played On (1993), Philadelphia (1993), Jeffrey (1995), Red Ribbon Blues (1996), and countless others.

There’s a whole body of narrative cinema built almost entirely around and from the perspective of white gay men, their Black and brown counterparts relegated to the periphery and the underground. Russo’s inability to witness the advent of the New Queer Cinema movement of the early 1990s, where old guards like Derek Jarman found a revitalized importance alongside filmmakers like Todd Haynes, Gregg Araki, Todd Verow, and Rose Troche, among others. This movement in independent cinema seemed the only way to see pertinent perspectives across a queered diaspora, offering up the most creative and sinister deliberations on what being gay was like in the 1990s. (Haynes technically made the most apprehensive AIDS film with his 1995 metaphorical environmental illness drama Safe, through the lens of an ailing suburban housewife played by Julianne Moore.)

Outside of Hollywood, cinema does have the capability of contending with yesterday, today, and tomorrow, though the influence of political administrations tends to formulate parameters around acceptability. The influx of queer and Black filmmakers flourishing in the 1990s during the Clinton administration seemed to evaporate during the presidency of George W. Bush, and the AIDS-drama staple began to evolve as the LGBTQ+ movement made political strides for equal rights. In Hollywood, we saw this reflected through the critical and commercial successes of films like Boys Don’t Cry (1999), Brokeback Mountain and Transamerica (both 2005), which garnered considerable awards attention and utilized the first-wave tactics of employing notably cis and heterosexual actors to court mainstream acceptance.

Pauline Kael commented in her review of 1968’s The Killing of Sister George how Robert Aldrich’s “overwrought” direction was ultimately off-putting: “It’s best to clear the streets because he’s frightening the horses.” By the mid-2000s, we’d found a new coding system for placating the hetero herds. Consistently, notable films and television series have returned to the onset of the AIDS crisis to great acclaim, and far removed from the paralyzing, overwhelming terror of the past. Angels in America (2003), The Dallas Buyers Club (2013), It’s a Sin (2021), and even 2023’s Fellow Travelers caught the public’s attention from the safe realm of a better time, a more progressive place. But what’s going on behind the scenes in these prestige period pieces involves an evolution in casting.

With the Supreme Court’s legalization of gay marriage in 2013, the success rate of LGBTQ+ assimilation into the heteronormative became inevitable, but again reflecting how those highest on the hierarchy benefitted most by juxtaposing the continual rejection of trans and non-binary-identifying members of the community. In turn, strengthening the argument regarding cinematic representation and who should be allowed to play LGBTQ+ characters in an industry seemingly obsessed with the power of celebrity bestows carte blanche upon heterosexual actors whose affiliation attracts financing.

And while these kinds of discussions, which would have been unprecedented not even 20 years ago, reflect a hard-won progress, something much more subtle and subversive has been happening all along. While not entirely indiscernible, there has been a significant shift regarding what kinds of queer narratives are being told, where neither disease nor eroticism are the defining characteristics. Because…what is queer cinema now? What are the fears we’re collectively examining now that the AIDS crisis has abated and sex no longer directly equates with death?

In 2023, we saw a large volume of exceptional films from queer and trans perspectives that benefited from no longer being shackled to niche audiences. Their respective resonances allowed their LGBTQ+ characters the chance of reflection upon their pasts, with futures as open as their demystified heterosexual counterparts. In retrospect, it was a bountiful year for representation in not only quantity but also enlightening quality—in ways suggesting an imperceptible acculturation because they’ve not been huddled together as evidence of a watershed moment. Sex as both a formative experience and a cathartic tranquilizer blossomed in unexpectedly accurate scenes, conveyed by filmmakers intent on authenticity.

Ira Sachs’ singular Passages (2023), where a narcissistic film director played by Franz Rogowski can’t decide on which lover he can more easily control, results in a sex scene with Ben Whishaw that actually felt like a passionate and even despairing attempt to reignite their relationship. It daringly accomplishes a rarity in successfully conjuring titillation without divorcing itself from the repellant reality of its protagonist.

Two stand-out film releases from 2023 reached the top tier of self-actualization for their characters, albeit utilizing almost completely opposing tones and techniques. While he’s long been one of the most prominent contemporary directors exploring relationships between gay men, with his 2011 masterpiece, Weekend, and the acclaimed series Looking Andrew Haigh also inserted his own experiences into All of Us Strangers, an adaptation of a 1987 novel by Taichi Yamada (which Nobuhiko Obayashi, the famed director of the 1977 cult classic House, initially adapted).

Haigh centers his version on Andrew Scott’s Adam, a lonely screenwriter living in a recently constructed and almost completely unoccupied London high-rise. When propositioned by his drunken, equally lonely neighbor, Paul Mescal’s Harry, he rebuffs him. Having committed to write something about the tragic accident that claimed the lives of his parents in 1987, Adam decides to visit his childhood home, now long vacant. Surprisingly, there he discovers his parents (played by Jamie Bell and Claire Foy), exactly as they were the week they died. Their reunion, which takes places across several visits, creates a surge of catharsis as his parents are curious about the man Adam’s become, their reactions to his sexuality informed by the cultural fears and beliefs of the period in which they died. This is juxtaposed with his suddenly accelerated romance with Harry, a younger man from a different generation, who didn’t grow up viewing sex as a potential death sentence. While Harry has his own emotional turmoils the film eventually unveils, Haigh straddles this cross-generational divide between gay men, suggesting how self-imposed emotional purgatory might be best quelled by directly confronting the past as the only way to move forward, but never to dwell with one’s ghosts for too long.

As much as Haigh’s film requires a high suspension of disbelief while also embracing sentimentality, Andrea Pallaoro’s Monica vehemently eschews these tendencies. The second in his thematic trilogy of femme-centered isolation (the first being 2017’s Hannah), the titular figure played by Trace Lysette is a transfixing woman who is also adrift in emotional limbo. Pallaoro cages Lysette in with an aspect ratio meant to suggest the heteronormative box imposed upon her, with close-ups further forcing our attention on the subtlety of her behaviors as we puzzle together how Monica is a trans woman whose ex-boyfriend has cruelly dumped her.

When her sister-in-law, whom she’s never met, reaches out to inform Monica her mother (Patricia Clarkson’s ironically named Eugenia) is dying, she’s suddenly forced to confront a past she fled years prior. More frustratingly, she must reconfigure relationships with family members who aren’t initially sure who she really is. While trans representation in cinema remains acutely deficient, Lysette’s presence and performance is a profound step in a neglected direction. It was only 40-plus years ago when someone like Karen Black playing the prodigal-son-turned-trans-woman in Robert Altman’s Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982) was a sensationalized revelation, distracting from the interiority of the characterization.

Both Haigh and Pallaoro end their narratives at an ambitious juncture, arguably with a viable sense of hope, suggesting, at the very least, a next chapter for these people who have confronted a void, realizing they no longer have to be defined by the past. And maybe this makes queer stories more frightening than ever, because the unpredictable unknowns of life have always been more infinitely unnerving than the finality of death.

Watch Nick and his husband Joseph review (and spoil) films on their YouTube channel, Fish Jelly Film Reviews. Their podcast of the same name is available everywhere.