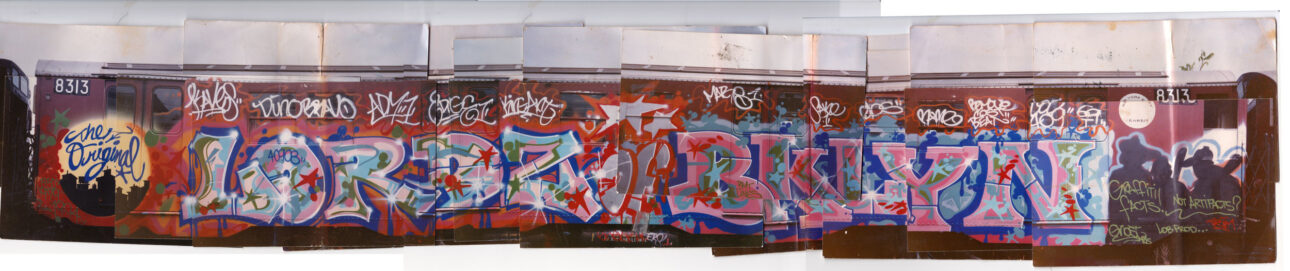

Herein lies the ink-stained testament of NYC native and early ’80s hip hop graffiti-pioneer Mike McLeer, aka KAVES, who—after a career-complicating biff and bust by the transit cops’ Vandal Squad—later hit it large with rap group Lordz of Brooklyn.

Nevertheless, from the tender age of just 10-years-old KAVES, fighting outta Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, made one hell of a mark on NYC trains and the city at large. Inspired by a cultural melange brewed from everything from “Rapper’s Delight” through Saturday Night Fever to G-Force, KAVES helped forge modern American culture.

KAVES knows inside-out how rough it got back in the day in pursuit of the perfect hit on the NYC Transit Authority. Mind you, the day ain’t quite over, not with graffiti writers—even from France—still getting schmattered when drawn like moths to the inky flame of subway adventures.

So pop a cap on what you’re doing, grease your nunchucks, and huff these fumes.

SPIN: When you saw a train roll by that you’d painted — what was that feeling like?

KAVES: Oh, yeah — pure accomplishment and adrenaline. Equivalent to seeing your name on a billboard in Times Square. Your name in Hollywood. Your name in lights.

There was a train car that me and [a buddy] Revs did that said, “From here to Hollywood.” We really felt like we were celebrities — like we were on our way to becoming famous.

Would there be passengers in the trains when you hit them? Or were you waiting for no one to be around?

When you learn how to be a graffiti writer, you’d find out that there was tunnels with lay-ups where the trains park at night before rush hour, and train yards. And you go there.

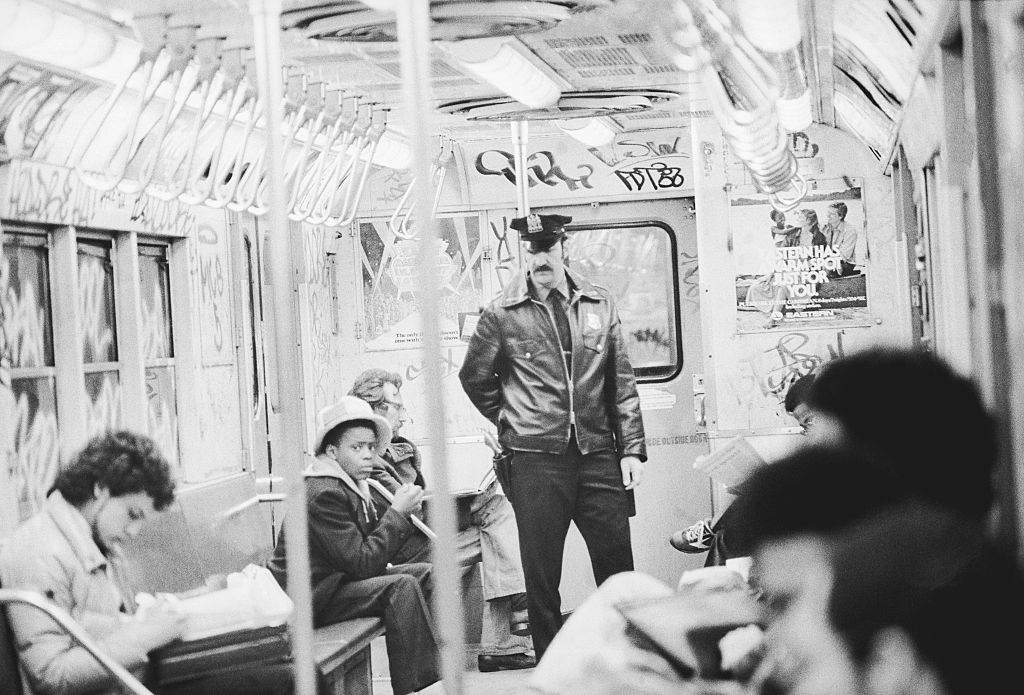

People did something called ‘motions’ where you’d get on a train and tag it up with people in it or not, but that was very brazen. And you wouldn’t be able to do a lot of that. You’d mostly wait for the train to be parked at night.

What was the air like in the tunnels?

Piss-smell, train brakes, newspaper, charcoal, wood – old wood that smelled like a boardwalk. It was hot. You could cut the air with a knife. You could bottle the smell and sell it for millions of dollars because, for children in New York City, it’s summer camp.

How long would trains stay painted like that before the Transit Authority painted them back?

A week or two. They buffed ‘em pretty quick. And other writers would go over your cars.

Did you get chased much by transit cops — the Vandal Squad?

Plenty. There’s two kinds of graffiti writers: one that gets caught and one that hasn’t get caught yet.

What time were you getting into the tunnels and yards?

Three or four in the morning. We had an older writer that was a mentor: Ant was 15 years old, but he looked like he was 30 — he already had a full beard. He was like an older brother to us. In my bedroom I had a fire escape, so he’d ring the phone once and I’d jump out the fire escape and meet him in front of my door.

He’d say, “Hey, listen, if the cops grab us. I’m your older brother, and we’re going to meet our father on the construction site. And this would be our story in case anybody were to pull us over. And then we would go into a layup, say in Sunset Park, and do our thing.

We were always sneaking outta our house, hoping that our mother wouldn’t catch us. And we were starting to venture outta our neighborhood.

How hectic did these late night excursions get?

One time I took [my brother] Adam alone with me as a lookout. This piece [of graffiti] was going to be a special piece. I think we were going to East New York or Flatbush to paint the Franklin Avenue Shuttle. This was when I started becoming even better at piecing, and [I was] getting very competitive. I was gonna meet these two other writers: Paulistic and a writer named Surf — brothers, and part of a crew out of Flatbush.

We were gonna do a whole train car. So I took Adam and we went to go do this train. Let’s say it was in a bad part of the neighborhoods, right? A little bit wilder.

It was a Sunday morning, and the train was laid up in the middle of the tracks against the wall. You have to be able to climb up the wall to paint a whole car and, ‘cause we’re five-foot-four, you have to be like a rat. Paulistic had cerebral palsy and had a hard time climbing, so we were helping and we doing this whole train car, early Sunday morning — really early in the morning. I’m painting Japanese anime characters on the train car.

This train car’s gonna be real nice. My little brother scurries up the wall and he’s helping paint the top. Then another train comes. Usually they pass by but you hear the brakes. Odd for a train to stop next to another train, but it does and the doors open and a group of cops jump off onto the tracks and come running.

We hafta scurry up the wall, and up the wall there was a fence and you’d jump into backyards of stores and buildings. But Paulistic was having a hard time; we had to physically grab him by his hood and carry him over while these cops were trying to climb after us and they’re fucking pissed off — billy clubs out and fucking banging them against the train car, and we’re scurrying up the wall.

As I got to the top of the fence, my brother jumped over into an abandoned lot; Surf got over, they got Paulistic over, and then I jumped — onto a board with a nail sticking out of it. Went right through my PRO-Keds. I sat there stunned for a minute. I was more pissed off that we couldn’t finish this train car ‘cause it was coming out beautiful. But I had to pull my foot offa this nail. And I remember my little brother being super fucking scared.

We were like “Holy shit — run!” and the cops were climbing the fence, and we get onto the main streets and we’re running, and Paulistic dipped into a store and Surf is running, and a bus driver pulls over ‘cause we’re two white kids getting chased in a black neighborhood covered with dirt and shit. He doesn’t understand that the two black kids chasing behind us are with us. He thinks they’re chasing us. So he pulls his bus over and tells us to get on board.

Privilege was definitely shown that the bus driver would pull over and make us hop on board. But I’m glad to say that Paul and Surf didn’t get caught, and me and my brother got away. This ordeal was a typical thing for Brooklyn kids.

A cool thing was my mom didn’t care what you were or who you were. She would be making a pound of pasta for all my friends, and we would sit in the room: black kids, Puerto Rican kids, Chinese kids. That’s what graffiti was all about. It was a real diverse melting pot. This is the way music was in the city, and the way the art was.

Cops do anything interesting to kids when they caught them?

When they didn’t want to go through the paperwork [of an arrest] they would take the spray paint and write on you, and go, “How you like it now?” Plenty of kids got tagged up.

One time we got chased some of my friends came into my [apartment building] hallway looking for me, and I was actually in a candy store playing Asteroids.

When I came back home, my hallway was covered in ink because the cops made them get on the floor and they poured ink all over them. That was their punishment. Coz the cops didn’t wanna deal with doing paperwork for little kids, you know what I mean? So [instead] they give them a shakedown.

How’d you get the paints?

There was rules—a lot of rules—that you would learn when you were mentored as a graffiti writer. You didn’t buy your tools. You didn’t buy your paint. And most of the time you were coming from a background where you didn’t have money to buy paint, so you’d have to go racking [stealing]. You’d steal from the hardware stores and the supermarkets.

Wear baggy stuff?

Yeah. You’d make sure that you wear jackets extra large — most likely your father’s. We would tuck ’em into the back of our pants, and then leave the front open. Then you would just bring everything to the back of your jacket.

Did you have to keep roaming farther and farther to steal?

Yeah. You didn’t wanna burn out your rack, so you had to. You had to go to all different neighborhoods and rack and then come back weeks later [to re-rack the same stores]: change your outfit; disguise yourself.

The supermarket was fun because they used to have prices on the cans. In our neighborhood there was a supermarket called Grand Union. They had purple ink for marking prices and we called it store ink. They used it to refill the marking machine.

So you would take that and get it outta the store, and fill up your markers. They would be for tagging the insides of the trains with your tag, your name. That [tagging] would be a fast thing. A lot of kids wrote on the inside for the thrill of writing.

But the outsides became the canvas. So if you became a graffiti writer, that was a piecester, and you would go out to do something called the burner, and that’s where you would make an elaborate piece. That’s what I was mostly into. For me, it was art. It was something that I wanted to express, and I was competitive at it. My brother, Adam, was more into hitting the insides.

Everybody had their thing. If you didn’t have the time or cans of paint to paint outside, most likely you could afford getting a marker or find a marker and write on the inside. So the insides and the outsides of the train were definitely a place to express yourself.

How did you get into this? Something kickstart it for you?

When we moved onto the block, there was this group of kids tagging all over the school yard and on my block, but the other thing that happened around this time was the movie, The Warriors, came out.

The Warriors (1979) set like a trend. It sparked it. It started this thing. It was very popular. It was all over the news how it was dangerous, and so all the kids wanted to see it. And in The Warriors there was a kid that took out a spray can. When you got a chance to see this film—the adrenaline—when little kids go, it has a big impact. That movie had a big impact.

So everybody after that movie was going into the store and robbing and tagging up the staircases, and the character in that movie that definitely stood out was the New York City subways.

So that movie, the Warriors, had the direct and unambiguous effect of increasing juvenile delinquency?

Exactly.

So you could imagine the summer of 1980, like after ‘79 in that movie, we’re coming offa these incredible ‘70s movies — Rocky and Saturday Night Fever, which was filmed in my neighborhood. It was like the neighborhood was famous in itself, and we lived on 92nd Street: in the background was our apartment building. And on a hot summer night, if you needed to escape, if you needed a place to get away, you went to the rooftop and you had this million dollar view.

And we’re dirt poor. We’re broke. But we had this million dollar view of the Varrazano Bridge, and the Tony Manero [John Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever] story was pretty close to real life for us, because that bridge was a beacon of hope. It was the only stable thing in our lives at the time.

I used to look at the Varrazano Bridge and say to myself, “One day, I’ll cross that bridge and, you know, I’ll become famous.” It was very much like Tony Manero: life imitating art, art imitating life.

I avoided watching Saturday Night Fever for ever because I thought it would just be more disposable shit, but when I eventually saw it I was surprised; it’s a gritty urban story.

It’s a pretty true to life story of what it was like growing up in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn: besides the disco — if you take away the disco and you just talk about growing up in a neighborhood where there’s not much for you. Either you grew up to be a gangster or a cop. We were under middle class because my mom was a waitress, and we were really on our ass.

We didn’t have a pot to piss in, or a window to throw it out.

But the one thing that we did have was a lot of optimism because we came from a good looking family and a talented family. My old man was aspiring to be a gangster, and he was in a greaser gang in Brooklyn and he liked cars and hot rods, and he would come see us and come roll on us on the weekends or Sunday.

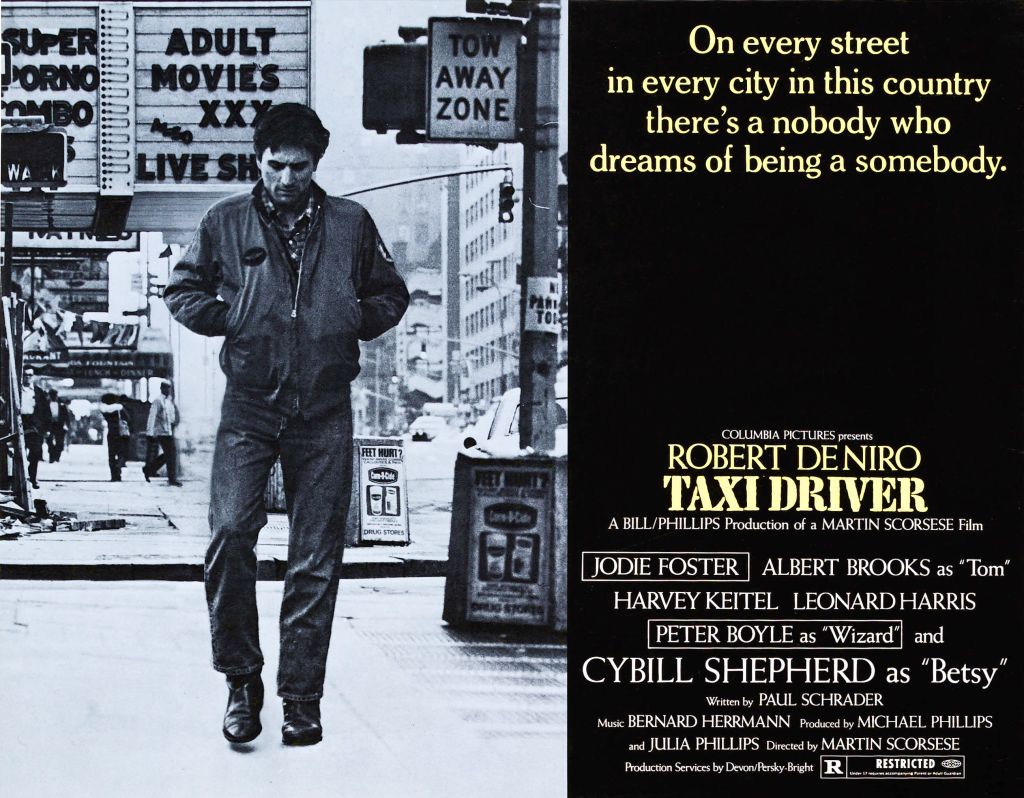

Him and my mom would be fighting like cats and dogs and it was a troubled time for us. So we were looking for something to get us out of this grind. And as a little child, I was a big lover of cinema, and these movies were inspiring. Like, what is gonna be my ticket outta here? That’s what it’s like, what’s my ticket for these Brooklyn kids to make good? Yeah, the ‘70s.

It’s the greatest era of American movies: the Jack Nicholson ones [Five Easy Pieces, Carnal Knowledge, The Last Detail, Chinatown, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest], and Taxi Driver and more.

Yeah. It’s a gritty time and raw, but it’s a very creative time. And my brother’s a little younger than me, and he’s the little brother that follows me around. But when we meet these kids on our block, and we’ve seen the Warriors, and they’re grabbing markers and vandalizing and they’re showing up in the school yard, you start to understand — this is more organized. And they’re carrying black books that have designs in them and they tag-up the school in hand styles with bubble letters. For an artist, it catches your eye.

There was these two kids, brothers, that showed us a bag of markers. They were like: “Ten bucks, we’ll give you this bag.”

Me and my brother was like: “All right, sure. What’s in it?”

That was the first time we really seen what the real graffiti marker was. It was a Pilot and a can of Flo-master ink. So it was like real official tools of the trade of a graffiti writer. ‘Cause before that, we just had the El Marko, and that was kind of toy-level for graffiti. They also had a mini-wide marker, which was a three-finger wide marker. And there was a BB gun. I remember that.

You could buy this whole bag—your juvenile delinquent starter kit—for 10 bucks.

Later on we would take the felt out of the Pilot marker. It looked the size of a stick of dynamite, and when the marker dried you could even make it an even fatter marker by going into your school, a classroom, and robbing the eraser from your school teacher. And you would take that Pilot marker and pull off the top and take the felt out, bend the felt in half, and stick it back into the marker. And then we would take an Eveready battery, and we would hollow out a battery, and we would make a cap so it would make the marker smaller, but fatter.

We called that the TNT, after a stick of dynamite. That was a homemade Brooklyn marker that you learned from the other kids. Those brothers sold us this bag of markers, and now we became more official. Now we had the markers, we have talent, but we needed a name. That was the biggest hurdle — finding a name in graffiti is like a rite of passage.

There was a local legend, a graffiti celebrity and hero around our neighborhood whose name was Rodney Rees. He was an older guy. So my mom hired the local neighborhood girls to babysit my sister, Chrissy. And there was a babysitter named Maryanne that Rodney had a crush on. So he would try to come over to kiss up to Maryanne, but he had to get on our good side, and we’d be sitting there in the street.

Rodney took a liking to me and my brother, Adam. He seen me toying around in the street, and said, “What are you doing?”

I said, “I’m trying to look for a name.”

He looked at me and said, “You got some talent. Well, my older brother just retired.”

His older brother, Frankie, had retired [from graffiti] at the age of 15.

So he said, “I got a name for you. His name was KAVS.” And right in the street he handed that name down to me.

A year later, when I started getting good, I added the ‘E’ in it to make it KAVES.

There was another guy across the street that gave the name to my brother: YR. He was the Young Writer. I don’t know why it was YR, it should have been YW, but, you know, graffiti writers — it’s whatever flows nice.So my brother got the name YR, and I was KAVES.

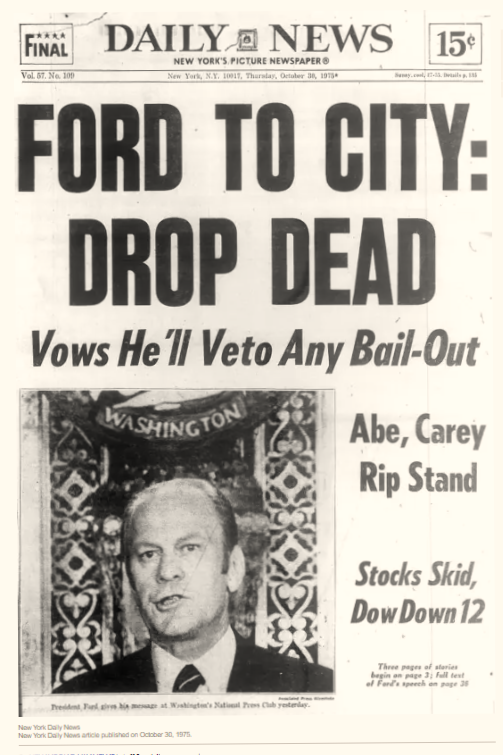

And I picked up on it really quick. That summer, Rodney would come by to see Maryanne and take me out and mentor me—show me the ropes—‘cause there’s so many levels of graffiti. And at the time, you know, you’d hear about subway graffiti, of course, that’s where all the claim-to-fame—all the famous stuff—happened. subject for graffiti because it was us against the city, because the city wasn’t doing shit for us

Anything that was Transit Authority was. I think [President Gerald] Ford told New York to drop dead [he declined a Federal bail-out of the city’s finances] because there was this overall thing: us against them, like us against the city, because the city was broke.

Little kids have to find an enemy. And it was the New York City Transit Authority. It was like a free canvas because the trains and buses would travel across the boroughs, and from one side of the city to the other. So that’s what you would write your name on to become famous.

Did you know people who got killed or injured doing it?

Yeah. People got injured all the time, and there’s plenty of graffiti writers that died in the tunnels trying to paint a train or they got caught around the turn when oncoming trains were coming. It’s dangerous.

Did it put a chill through things when people died?

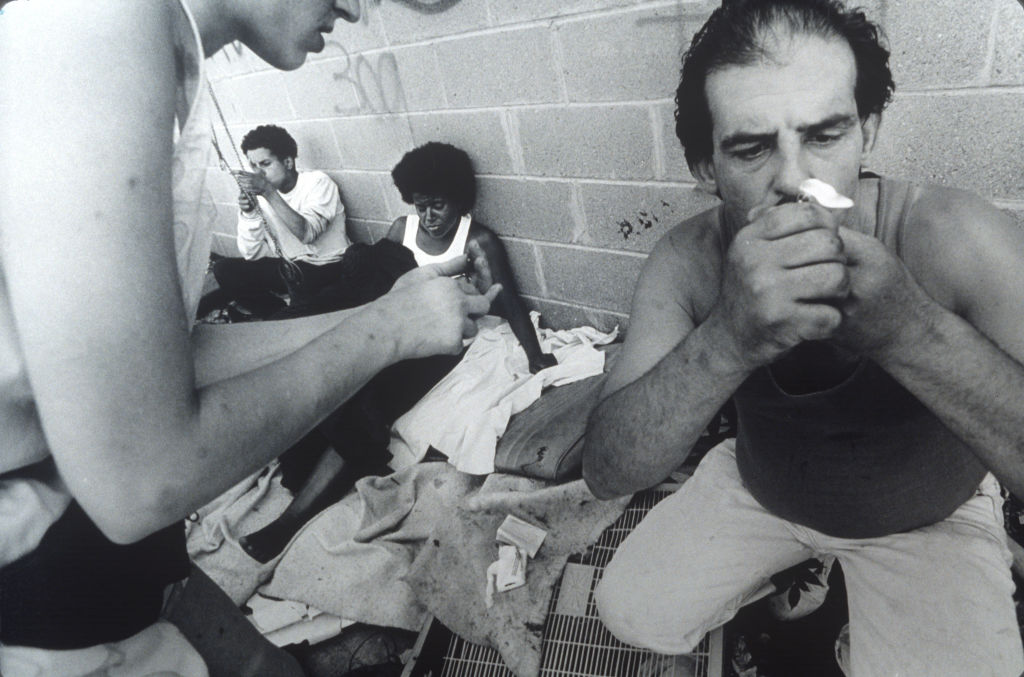

No. When you’re a child you think you’re invincible. And listen: a lot of graffiti writers came from broken homes, and there was a lot of heavy shit going on at their houses—a lot going on in these neighborhoods with depression and drugs and alcoholism; a lot of pain—and graffiti was a release. It was a way to get your mind off it, or it was your therapy — a way to express yourself and show you were here: to make a mark and show that you counted or that you belonged.

How could you spot other writers on the streets?

Ink. You were home-making markers, and working inside a train car some people were smart enough to bring gloves, but most of the time you wrapped masking tape around paper towels or something. But whatever you did you would always get it all over your pants, ’cause you would hide the marker in your waistband. So you’d always have ink around your waist. Using Brillo pads to take it off was never fun. But yeah, the way you recognize the graffiti artists was the ink. The ink on their hands; the ink on their sneakers. My brother talks about it even in a lyric in one of the Lordz of Brooklyn songs, “Tales From the Rails”, about how you could tell a writer by the ink on his hands.

Were writers in danger if rival writers or crews spotted them?

There was a lot of beef—a lot of drama—because other graffiti writers were either after you for going over their stuff or they were jealous of you. There was always problems. So there’s a lot of fighting that was involved with graffiti. It was definitely a gladiator sport.

You got caught in some trains, or in tunnels in certain neighborhoods, you hadda fight your way outta there.

Adam was very sharp with his tongue, but he was a little guy. I’m his older brother, so he definitely got me into a bunch of scrapes with graffiti writers or kids in the neighborhood where I had to stick up for him or, you know, stick up for the crew. Sometimes there would be arranged fights where writers would meet and fight it out. That’s how some beefs got squashed and settled. There was plenty of it.

Were other neighborhoods no-go zones?

Definitely. You couldn’t go into plenty of places and neighborhoods. They would rob you or take your markers — that was called vamping. Older writers would get rough or chase the younger kids. It was like kill or be killed — like you would be the one that would do that or they’re going to do it to you.

It was like this throughout all the boroughs—the Bronx, uptown, everywhere—and there were thousands of kids writing. It was probably 10,000 kids throughout the city.

But if you were really good and they respected you, sometimes you could go into other neighborhoods. I had a partner named Lask that was from the Killer Hill projects on Staten Island. He was one of my closest friends. And he had to make sure that people were cool with me coming there because it was off limits to some. He was a prolific graffiti artist that went on to manage the Wu-Tang Clan.

Kids use weapons when stoushing or robbing each other and stuff?

There was cats that was feared, especially in the Sunset Park area.

The legendary Mr. R would come into a layup with a shotgun. Cats had guns. Cats had Buck knives, switchblades, brass knuckles, baseball bats, and nunchucks. It was full-on fucking war.

And a lot of the graffiti older guys came outta the gang culture, so they still had their leftover weapons.

What was your weapon of choice?

Nunchucks. I was a little guy. My mother threw me into martial arts at a very young age. And as a kid in New York City at that time, Bruce Lee was a hood idol. And around my time everybody was ninja crazy. So I had blow guns. I had ninja claws, and I was good at the nunchucks.

Use ‘em on anyone?

Listen: it’s like this. I was really good at what I did — graffiti writing. There was a lot of guys around that were bigger, and all you had to do was piece their name or hook them up with some style, and they had your back. So it was always smart if you had a crew to have a couple of goons with you as well. But everybody needed to know how to fight. Unfortunately, that was a part of it, and the neighborhoods got even more unsafe with the crack epidemic that also made graffiti kind of die.

Crack did? How’d that work?

That’s when graffiti started to die down on the subway. It had a lot to do with the crack epidemic, ’cause a lot of legendary graffiti writers started getting hooked on crack. And a lot were dealing crack, so cats that had been getting their kicks writing graffiti and were even super talented got hooked and started selling drugs. If you got hooked on crack, or if you were selling and you were making money, you weren’t writing, you weren’t running around trains anymore, you know? It swept through the neighborhoods. People were robbing their grandmothers. And now you had to fucking deal with the politics of drug dealers. And some of those kids that were bad kids, now they graduated to bad as shit. So the graffiti movement of the early eighties got off-track, no pun intended, with crack cocaine.

How’d it all end for you?

One of my friends—rest in peace, he passed away—was the first kid to have a car. For his 16th birthday his mom bought him white Buick Regal. So now this Buick Regal afforded us to go to different neighborhoods and different train yards. So we would fill up the trunk with spray paint. So a few of us Brooklyn guys went to Queens, to Fresh Pond Yard, ’cause it was a great yard to paint in.

My partner Revs was doing a Marvin, the character Marvin, with his piece.The cops, the Vandal Squad, that was put together to battle graffiti was basically a bunch of 20-year-old guys, 23-year-old guys, chasing 13-year-olds and 14-year-olds around the subway. But these guys watched us paint this train call for a couple of hours. They were watching us from inside train cars and waited for their time to jump.

Then guns blazing, they chased us under about three or four train cars. They chased us down the tracks to a hole that we cut. I wasn’t lucky. I was the smallest one outta my crew, and I fell a couple of times on the gravel. This young cop was cursing me out that he is gonna kill me, he’s gonna break my face. Two of my friends got away through the hole, but he caught me by the hole.

The guy threw me around like a ragdoll. I was about 125 pounds soaking wet. He gave me a couple of punches, a couple of slaps, and handcuffed me to the pole in the train yard. I think I scared the shit out of him when I climbed on top of the guard for the third rail: he turned white and gave me a couple of smacks, because he thought he was gonna get electrocuted with me. He was handcuffed to me, you know.

Three of us got arrested. They lined us up against the train car, took pictures of us, and then bring us to the station and try to get us to flip on our friends, you know?

That’s when my father walked in. My father was a half a goodfella to begin with and, when he seen them trying to fucking shake me down for my friends, he started flipping on them. He tells ’em: “Get the fucking cuffs off my kid.”

My father gave me the riot act afterwards. And he gave me the goodfella speech about how “You keep your mouth shut,” and that was it. I thought I was gonna get a beating from my old man. But he basically told me about some of his antics as a kid, and I didn’t think he felt like painting trains was something that grown-ass men should be giving you a beating for.

The next day [when the bust made a splash in the newspaper] made me kind of famous. And that’s what graffiti was for. So it was silly every time the cops printed something about graffiti; graffiti riders lived to get fame.

But it pretty much took the fight out of the dog. After that I was going to court and paying summonses and all that type of shit and doing community service. Me and Adam had to figure out another way that we can continue on.

I still painted; I still did graffiti, but now I had to figure out other ways. So I painted more above ground. And because of the recognition, I was able to parlay it into commissions and work. At that time, I’m already 15, 16, and now I’m trying to figure out what I’m doing with my life.

That’s when we created the rap band: the Lords of Brooklyn.

This interview has been edited for clarity.