To get the lowdown on the necessities for any real bombing run in early ‘80s New York, we consulted Lordz of Brooklyn rapper, lifelong graffitist (dude started hitting trains in ‘81, at age ten), younger brother of storied NYC artist Kaves, and current groundbreaking rug-bomber, Adam McLeer, formerly known by the NYPD as the vigilante tagger “YR” and “ADM”. In fact, speaking of those damn blue-and-whites…

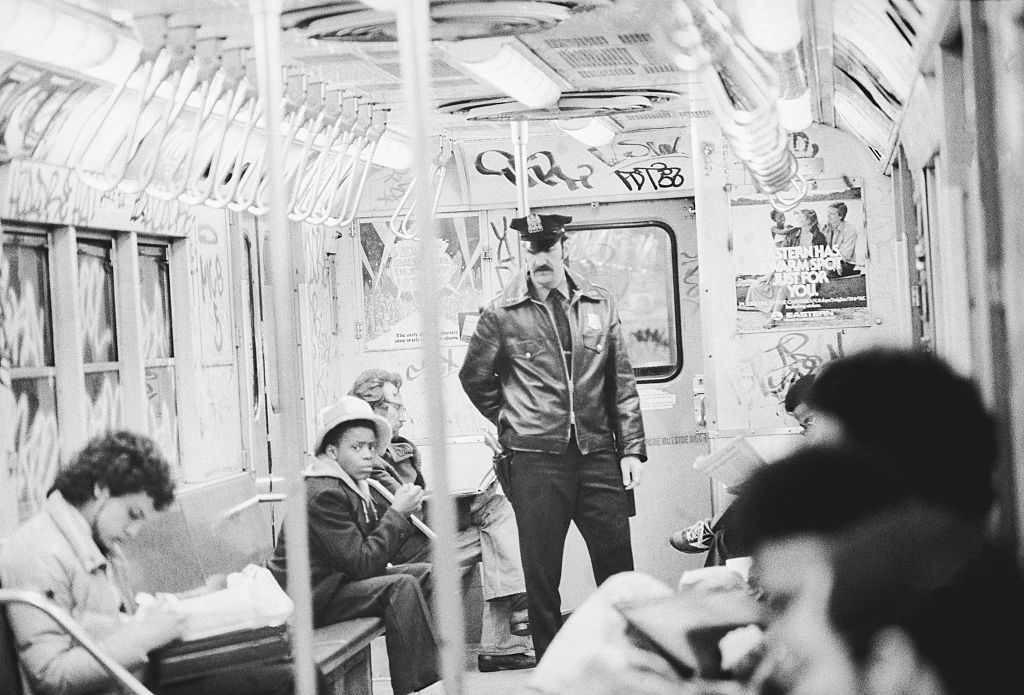

NYPD VANDAL SQUAD

Legend has it that the first truly memorable New York graffiti appeared in the mid-50s, as “Bird Lives!” tags, paying homage to the gone-too-soon jazz genius Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker, began popping up. At the dawn of the ‘70s, graffiti as we know it first reared its beautiful head, as writings of groundbreaking artists like TAKI 183 and Tracy 168 began to appear on trains traveling throughout the city.

A true and dedicated graffiti-art movement (or to others, a worthless and destructive visual plague), developed throughout the ‘70s, until by decade’s end, graffiti had become a serious NYC crime wave, spreading from the Bronx and Washington Heights into all five boroughs— especially Brooklyn. In 1980 the NYPD fought back, unleashing a specialized, anti-graffiti task force called the Vandal Squad.

“Since graffiti first broke out, NYPD has always had some form of the Vandal Squad. There were transit cops for a minute too, but in the late 80s or early 90s the city dropped them. The Vandal Squad though, the writers knew about some of them, the worst ones. It would be like you know, Frank and Eddie—‘Look out for Frank and Eddie, they’ll kick the shit out of you and fucking handcuff you to a train, and in the morning bring you in to the station.’

And as a matter of fact, I think they have a bigger vandal squad now and they’ve got even worse graffiti going on. Because these kids are fucking tearing up these trains right now, top to bottom, whole trains. They’re going insane, I got a guy that works in the yards that’s been sending me pictures of the trains pulling in.”

TNT BOMBERS

Early graffiti writers who worked inside trains and stations sure as hell weren’t using markers of the kind that currently reside in our pen and pencil drawers at home. No fine-point Sharpies, watery dry-erase markers or child’s Crayolas—serious city-writing demanded a big boy (or five), custom-crafted ‘TNT Bomber’ markers, filled with customized ink.

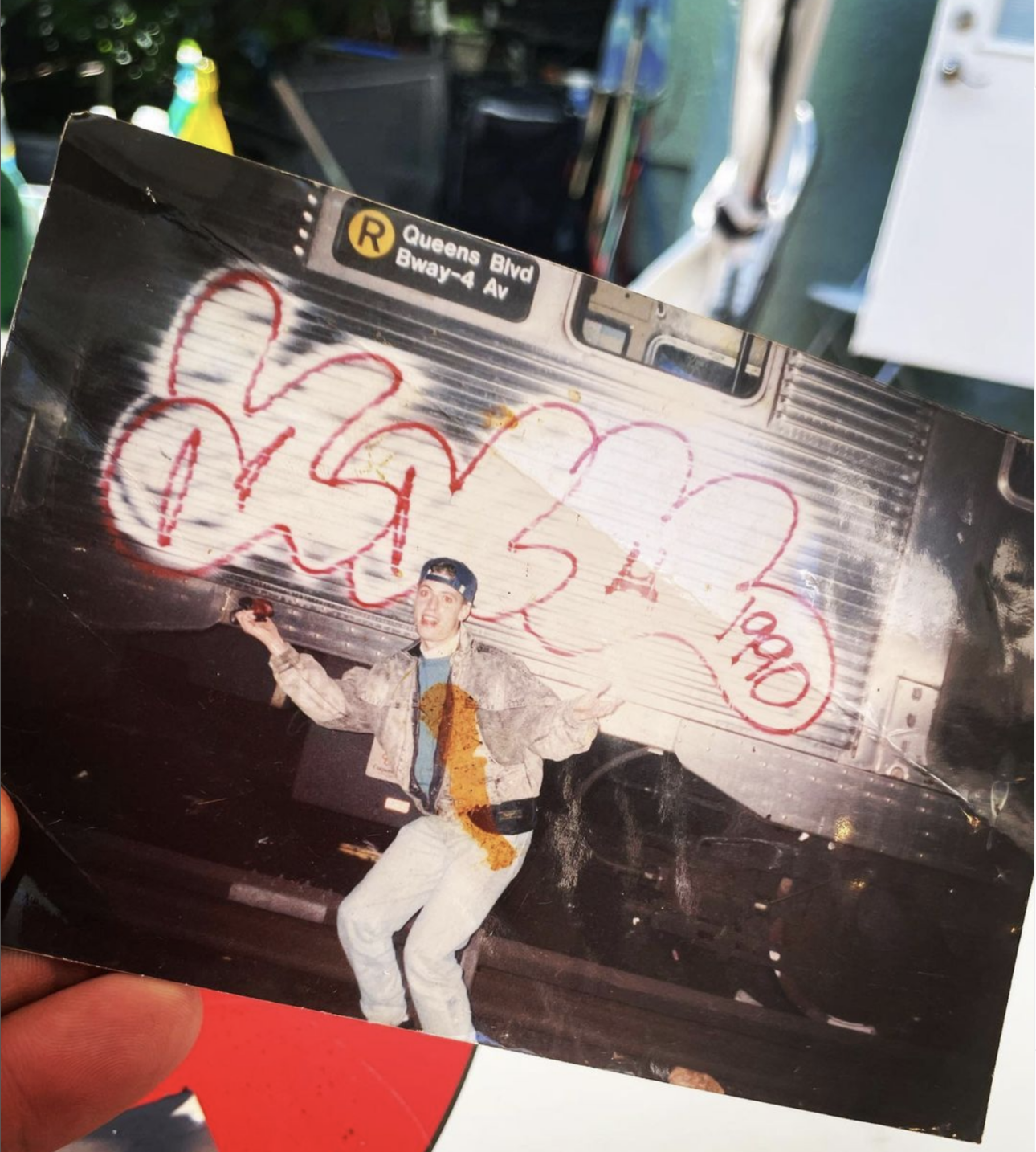

THE INK

“As a young writer mixing different ink colors together, you’d figure out your own personal ink—certain ounces from this color and this one, makes that one. And man, combined with the TNTs, that was just like, destruction. With the TNTs the whole train inside would get crazy, it wasn’t just black ink, there were purples, there were greens, there were reds.

Stationery stores were selling the ink, but they were rare. And you couldn’t even get the ink at every stationery store. When they did carry it though, they were good inks. Most of the time we robbed them. There was this one specific ink, if you could just find it, it could go over anything with the TNT because of the hard-eraser tip. The flow of the marker was just genius.”

PILOT BOMBER

“The bombers were made in all different ways. There was one that was made with a Pilot marker where you would reconstruct the whole thing. You take the whole top off and pull the eraser that’s inside of it out, pour your ink in. And when you’re mixing inks, if you pour an opaque in with a regular ink, it gets kind of goofy down there, so we would then drop a ball bearing in and you would shake it up to mix it, similar to spray paint. Lastly, you would rob a school eraser, one of those old ones, the chalk erasers, you would fold a piece of that into the marker. Then at times I would sew the tips so the ink wouldn’t drip out.

But see, then you couldn’t put the cap back on, that was the thing. So guys used to dig out D batteries to make a metal-tin cap that fits over the new tip you put in. You put some electrical tape around the marker to meet the new cap that’s going on there and it stays perfect. We learned it from the older hippie guys on the block that were graffiti writers when we were young.”

DEODORANT STICK

“You could also make a TNT with a deodorant bottle and once you have that felt eraser tip in, it lets the ink sit inside of the tip, as opposed to a jumbo marker you buy at the hardware store. Fill that jumbo marker with ink and when you turn it over it’s just going to pour out on the floor, but a felt-eraser tip makes it stay in there, but soaking wet, just soaking wet. It’s unbelievable.”

SHOE POLISH APPLICATOR

“One of those shoe dye applicators, the little plastic bottles that you would screw open to reveal a tip to clean up your shoes or whatever, graffiti writers like myself would dump out the shoe-dye polish, fill that up with the ink you’re mixing, put that in there and now you’ve got a seriously different type of marker. You can’t really buy those shoe dye applicators any more, unless you can find lots of them from the 80s and 90s.”

MINI- & UNI-WIDES

Though custom homemade TNTs were the ultimate weapon among early bombers, a choice few retail markers, namely the large, specialized kind designed for sign-painters and calligraphists, could still get the job done. For writers with swift hands and wide pockets, a quick shoplift-stroll through the stationary store could always net some pro-level bombing instruments. But to actually use them…you had to have the stroke.

“For standard markers, some people used Unique pens from art stores. They had some Flo-Pens from Flo-master that were really old that the really old guys used. That standard Pilot, which was sold in stationery stores as well. But then there were the markers that they called Mini-wides, with a felt tip. Those were made for calligraphy so a lot of art stores had them. There was also a fatter one which was the Uni-wide, like an oval marker, those were top choice. If you were for-real writing you had to have at least a mini or a uni. But the thing is, you had to know how to write with them, you know? The crazy thing is that I learned calligraphy in fourth grade and I started bombing in fifth, sixth grade, so all that calligraphy became good when I got a chiseled square marker.”

SPRAY CAN CAPS

Eventually, aftermarket spray can nozzles of all sizes and widths were produced for graffitists to write with specific line styles, as well as increase their can’s spray force—but during the ‘70s and early ‘80s, the only custom caps to be found were those swiped from foam and cleaner spray cans at the hardware store.

“They used to use WD-40 in the real early days, which was terrible. Put a WD-40 cap on a spray can and it’s just like an explosion of paint out of the cap. But there was this one company, Jiffy-Foam, that had multiple foam sprays. There was Kitchen Magic, Cabinet Magic, with spray caps built to foam out, so it’s a slow spray. And it’s a large cap, so now stick that thing on a Krylon can or a Rust-oleum can, boom, you’ve got a fat-cap.

Now this was the ‘80s, everybody was robbing stores, so everybody was staring at everybody. For the kids, It got hard to steal whole cans from the hardware store, the manager and the cashier were usually staring at you, so…you’d have to be quick, pull the top off the can, grab the spray cap with your teeth, right? You’d bite it off, keep it in your mouth, then you close the can, so it looks like you didn’t do anything, and right back onto the shelf with it.

Now you just go down the line. You do like 10 of them, 12 of them, and you’re popping caps, and you got like ten caps in your fucking mouth. It felt weird, it was a weird fucking thing, but look, you know, this is how it started. Downside of that shit was I feel bad for people. We were little kids taking these caps, then you get some poor woman going into a store to buy cleaning foam, they get home and really need to clean, and there’s no spray cap on there.”

KEYS TO THE KINGDOM

In the days before programmable code-locks, plastic cards with microchips and facial ID scanners, simple metal keys were the only means of access to the NYC MTA’s most secure zones. For bombers, a ring full of stolen transit keys could make or break a mission—especially one hung with the vaunted MTA skeleton key.

“Keys, whoever had the keys man, you were in bro. And bolt cutters. But all the different keys were the most important thing to have—keys to get into the train station, even keys to get into the trains. Maybe you knew somebody, or were related to someone who could get copies, but really, to get them you would have to steal them. You know, you’d see the MTA guy walking up, you fucking gank their fucking key ring, and some had these special skeleton keys that got you into the train.

If you were doing outside pieces, you only needed to have the keys to the overnight exits—but if you were doing work inside a car, you needed the skeleton keys that opened up all the locks. You still had to have that first key, you know what I’m saying, but if you had those other keys man…then you get into the layups [where trains parked overnight], you open the train doors, everybody would jump inside. Some writers would have fucking keys that would turn the trains on man. There were writers that would turn the heat on in the winter.”

LESS-LETHAL WEAPONRY

For both aspiring graffitists and vets out for rec-league action between missions, tools of less impact than TNT bombers and tricked-out spray cans did exist. No less effective for artistic expression, just shorter-lasting than the big guns, shaving sprays and stickers were easy street art flexes.

SHAVING CREAM

“Remember how kids would do shaving cream pranks on Halloween? We use to bomb with shaving cream, but you couldn’t do that with a stock shaving cream cap. What we used to do is stick a twig or metal pin inside that cap, then burn it with a lighter so it would turn small and tiny. So you pull the twig out, now you got a skinny shaving cream cap that fires like, you know, 20 fucking feet. So that had us doing pieces high up on buildings with shaving cream.”

STICKERS

“In the ‘80s it was always the ‘Hello My Name is…’ stickers, or the huge rolls of the blank square ones. Woolworths or any stationery store, that’s where you thieved them from. And the post office stickers [blank Priority Mail labels], probably in the late 90s, that’s when that shit popped off. They used to just lay them out, and everybody was robbing stacks of them, so they would put them behind the counter.

But then all the writers figured out ‘Oh, wait a minute, you can just call the post office and ask them for a stack of stickers and they’ll send them to your house!’ For free! Just call or write to them, ‘Ok, send me the 100-pack’, and now you’re getting a huge stack sent to you.

You know what, I was just at the post office. And they’re back out, sitting right there, stacks of them. I took a stack just for the fucking hell of it. You know, you got that graffiti-writer in your blood? Take it just to take it? I got outside and was like, oh man, what am I doing?”