“The Teen Dance Ordinance … it doesn’t even sound right! You know what I’m saying? Like an ordinance to deal with teen dance? I don’t know what it could have been called to make it seem better, but it just sounded like enforcement.”

So says Keith ‘G Prez’ Asphy in a recording studio at Seattle’s NPR affiliate, and the frustration over one of Seattle’s dirty secrets is carved into his wry smile. Our conversation is part of a podcast I’m working on, about, you guessed it, the Teen Dance Ordinance, a set of regulations that severely restricted the opportunities for people under 21 to gather for the purpose of dancing.

Yes, it’s the plot from Footloose. In real life. In the 1990s! In Seattle! Seriously.

The TDO was on the books for 17 years, from 1985 to 2002. The rock and grunge music from then is enshrined in the Pantheon — everyone knows the hometown headliners, tortured-genius lead singers, and blue-collar fashion signifiers.

The story of grunge has been told in feature films, documentaries, books, and a zillion magazine articles, adding up to a sort of Gen X mythology that keeps drawing new generations of acolytes. Yet the TDO remains a blank space, an untold tale that never made it into the narrative. But while bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains were instigating a musical revolution, Seattle’s city officials were pressing down on live music, particularly black music and especially rap.

The TDO was authored in large part by King County Prosecutor Norm Maleng and enforced in Seattle by City Attorney Doug Jewett. His successor, Mark Sidran, took office in 1990, embraced Jewett’s paternalism and furthered it into a full-blown law-and-order crusade.

Sidran brought additional draconian “civility laws” to the streets of Seattle, dredging up old ordinances or launching new ones. He urged the Seattle Police to ticket people for sitting or smoking cigarettes on sidewalks, claiming to bring law and order to the streets of Seattle. In 1994 Sidran’s office even made it illegal to post flyers on telephone poles, eliminating the music scene’s traditional and primary means of messaging the public.

Either intentionally or cluelessly, Sidran was criminalizing the music community exactly at the time it was bringing the entire world’s attention to the city.

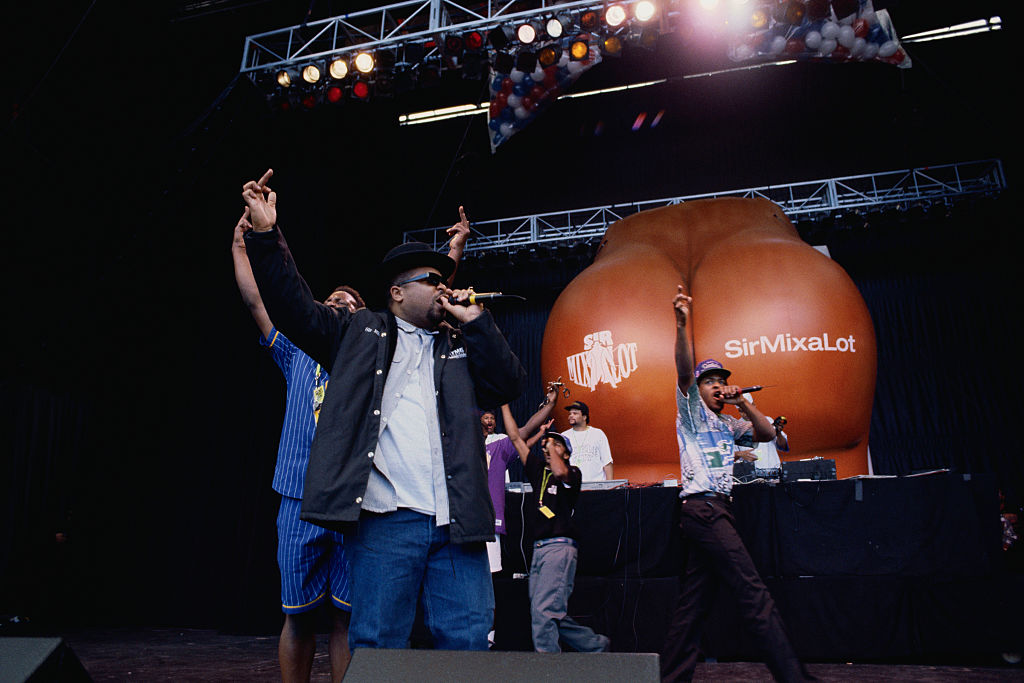

What’s more, as many promoters from the years allege, and as city memos and other communications from the era strongly suggest, Seattle’s morality squads deliberately and disproportionately targeted Black events which — in the ‘80s and ‘90s — most often meant all-ages hip-hop and R&B concerts and parties. Seattle’s rap royalty, Sir Mix-A-Lot had brought home a 1992 Grammy for “Baby Got Back” while his hometown authorities had their boot on the neck of the local music community, particularly its hip-hop scene.

Keith Asphy got his start as a teenage party promoter in the late ’80s, when the TDO was in full swing. (The law was birthed by the King County Prosecuting Attorney and a group of “concerned parents” following the shut down of an all-ages nightclub called the Monastery, which was housed in an actual church and run by an actual pastor, George Freeman, who happened to be a Black, bisexual former soldier who was also an architect of early dance-music culture in New York City.)

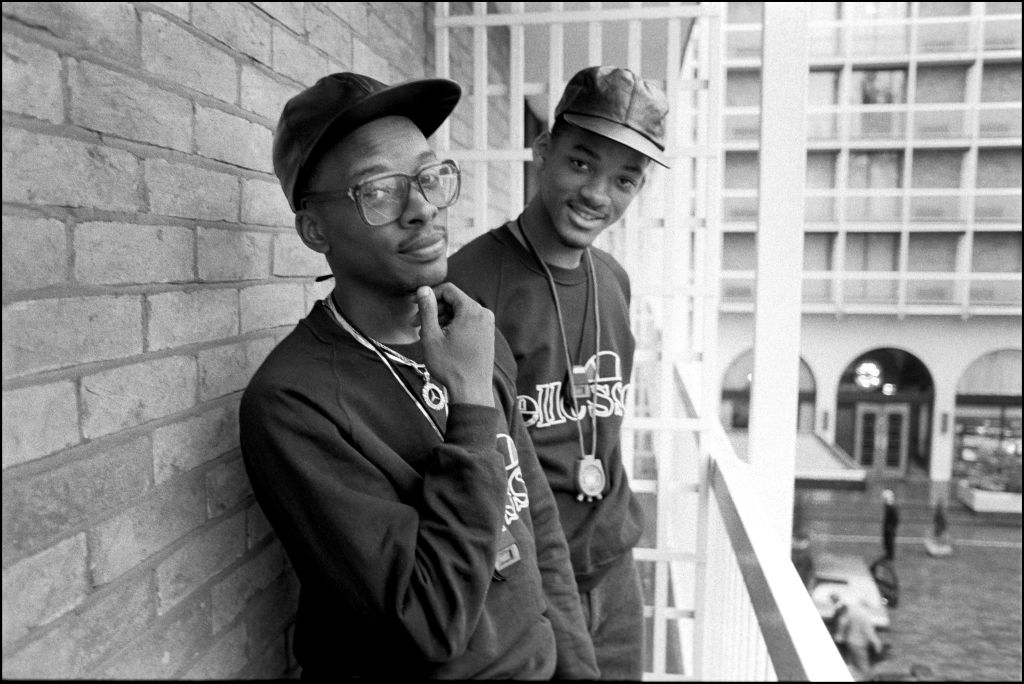

Keith was mentored on vinyl and Technics 1200 turntables in middle school, and soon the enterprising young DJ and social butterfly was putting on Seattle’s earliest hip-hop dances. With an 18-year-old partner signing the rental agreement, he and his adolescent crew would take over any available space that was not a bar — the Filipino Community Center on MLK Way, Odd Fellows Hall on Capitol Hill, the Sailor’s Union Hall in Belltown — to throw alcohol-free dances for people of all ages hungry to hear hip-hop on a proper sound system. The soundtrack was EPMD, Dougie Fresh, DJ Jazzy Jeff & the Fresh Prince.

“‘Rock the House‘ — we used to rock that joint like crazy!” he says.

By the early ’90s, hundreds of young people were turning out for Asphy’s events. For that reason he found himself under scrutiny from officers from the Seattle Police Department and Seattle Fire Department, who showed up to enforce the TDO. The ordinance worked not by banning dancing outright but by establishing a series of absurd — and absurdly expensive — regulatory hurdles that made all-ages events virtually impossible to produce. For instance, aspiring promoters were required to take out a $1 million event-insurance policy at the cost of several thousands of dollars, a steep bar for entry. More egregiously, they also were required to hire multiple off-duty Seattle Police Department officers to provide security. The latter Keith calls “a form of extortion.”

At $28 per hour, with a five-hour, three-officer minimum, and sergeants making $40 per hour, SPD was far more expensive than a private security company. “That’s how they started pressing us. It was like, ‘You either pay us or you can’t do it’,” Asphy says. “And even with nightclubs it was the same thing. If a nightclub didn’t hire police to work outside, then Liquor Control Board, Fire Department, all other types of enforcement would magically appear. And we were paying those dudes cash! We wasn’t 1099ing them dudes! We coming out paying six, seven, eight thousand dollars in off-duty police services.”

Was this shady dealing the result of selective, racist enforcement of the TDO? Asphy says that he wasn’t really tracking how the TDO was enforced in other circles, but he and other members of Seattle’s Black community are accustomed to such treatment.

According to former Seattle Police Chief Jim Pugel, who Keith says showed up at events as a junior officer to give him a hard time on several occasions, “I don’t know what the underlying feeling was or what the motivation was. I don’t think that was racist. It’s just a bad mix on a bad night. You know, a cop in a bad mood.”

(Years later, Keith caught an instance of SPD harassment on video inside his record store. Pugel, by then a lieutenant, was sympathetic. They’ve been friends since.)

Yet communiques between city officials and police surfaced by Seattle alt-weekly newspaper The Stranger demonstrate a pattern of suspicion, stereotyping and racial profiling more insidious and structural than a cop having a bad day. Evidence like this:

Black gangs hanging out are the problem.

Handwritten notes from City Council Member Margaret Pageler’s office, dated 1992

You can control the kind of people that come in: By music you play

By people you let in

By police presence

Hip-hop nights attract a boom-box crowd.

Club patrons are not residents of the area.

There is a relationship between a format that draws young African-American males and gunfire and violence on the streets. This music format in late-night, after-hours clubs is associated with criminal acts inside and outside the club. We have not said ‘change the music format.’ But we have pointed out the obvious problems with it.

Mark Sidran’s comments to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, dated January 11, 1994

I am not sure how this problem is going to be resolved short of… [changing the] entertainment format, thus changing the clientele that is disruptive.

Letter about a club’s weekly R&B night, from SPD Officer Jim Van De Bogart, dated September 26, 1995

[The Iguana Cantina’s operating manager Sharon] Fedde needs to come up with viable alternatives instead of the Hip Hop and R & B music on the Friday and Saturday nights. Ms. Fedde has not given any reasonable suggestions on a different type of music on the weekends.

Community Police Team notes regarding the Iguana Cantina which offered R&B music on weekends, dated February 7, 1997

This all fits with the experience of a slew of Seattle concert promoters. In 2000, Kate Becker put on more than 50 all-ages shows at the laundromat-cum-concert venue called Sit & Spin, including the White Stripes’ first Seattle appearance. These were daytime shows, 1 PM on Saturdays. Unlike Asphy, she didn’t go the legal route. She made sure the space was safe and relatively orderly, but she didn’t pay SPD or take out the required insurance policy. In fact, she says that she was actually trying to get arrested and go before a reasonable judge to argue against the TDO.

Police rarely showed up to her punk and indie shows, she says. But it was a different story for her Sunday-afternoon counterpart, Jonathan Moore. Moore launched the showcase known as Sureshot Sundays so his two-year-old son–and fans and performers of all ages–could convene at a legal, family-friendly hip-hop event without flouting the law. Before he died in 2017, Moore told Becker all about the selective enforcement he experienced.

“The police would show up at his shows, which were in the same exact venue that I was doing shows in, but he would get harassed much more than I would,” she says. “People are afraid of things they’re unfamiliar with, law enforcement included. So they walk into a venue and it’s full of young people who are engaged in hip-hop music and find it scary.”

Fear, it seems, led to overpolicing of events that carried even the slightest whiff of hip-hop. As veteran Seattle DJ Derek Brown, aka Vitamin D, told the Seattle Weekly in 2017, “Basically it was illegal to put the word ‘rap’ or ‘hip-hop’ on a flyer. Or even hip-hop images. If you even had some b-boys on a flyer, the police was coming, guaranteed.”

In a city once hailed by MTV and this magazine as Earth’s hottest hotbed for rock n roll, hip-hop was pushed further into the margins by both the media and the authorities. According to Dr. Daudi Abe, author of the book Emerald Street: The History of Seattle Hip-hop, the TDO’s impact on Seattle hip-hop is impossible to quantify. But based on anecdotes from the likes of Apshy, Becker, Brown and others, it was likely severe.

“Although this legislation may not have been aimed at hip-hop at the time it was passed, in practice and application it gave law enforcement free reign to — I don’t want to say govern the scene, but certainly to have an undue and unnecessary input into what happens within the scene and what doesn’t,” Dr. Abe says.

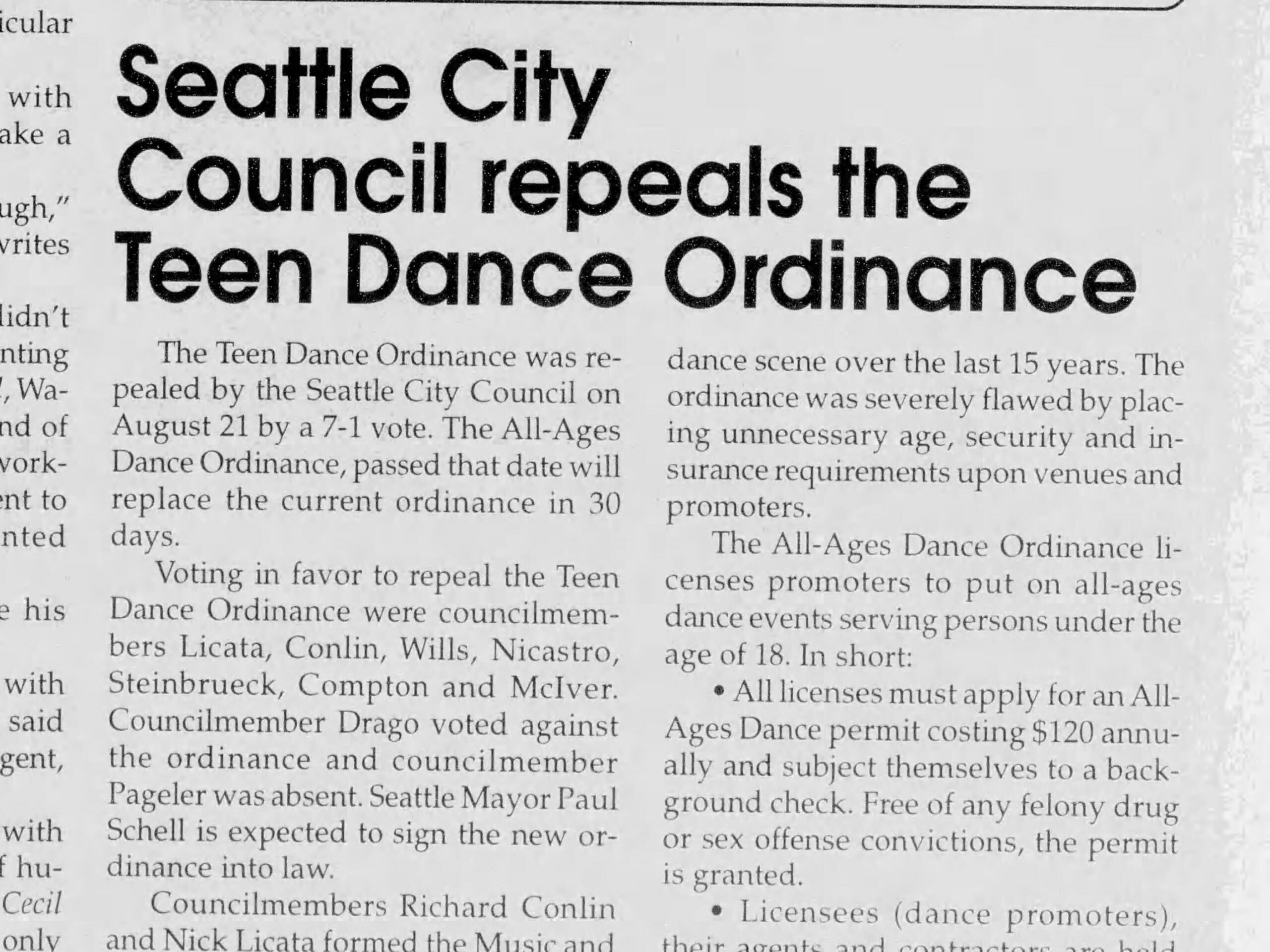

Seventeen years of activism, including lobbying by Eddie Vedder and other members of Pearl Jam, testimony before the Seattle City Council from Nirvana’s Krist Novoselic and Death Cab for Cutie guitarist Chris Walla, and more than one teenage flash mob in Council chambers, eventually turned the tide. The TDO was repealed and replaced by the more lenient All Ages Dance Ordinance in 2002. It explicitly recognizes the cultural contribution of all-ages music and the necessity for easier access to it.

By then hip-hop had achieved cultural credibility in America. Seattle, having weathered the World Trade Organization riots and exported Microsoft and Starbucks to every corner of the globe, had moved into the 21st century and started on its current hypercapitalist trajectory. The TDO faded into an embarrassing episode from the city’s past.

But as a story of authoritarian overreach, it remains relevant today.

Hip-hop was born from youth culture. Its Day Zero, which occurred 50 years ago this month, was a back-to-school party thrown by and for teenagers. Even in Seattle, Sir Mix-a-Lot got his start performing for teens at the Rainier Vista Boys and Girls Club in the pre-TDO early ’80s. And Jonathan Moore’s commitment to Sureshot Sundays gave the 17 year-old Ben Haggerty — then known as Professor Macklemore of the group Elevated Elements — his earliest shows.

The music cannot be severed from its all-ages origins, and young people will certainly never sever themselves from the music. Which is why, along with every act that suppresses expression and autonomy for anyone, young or old, Black or white, the Teen Dance Ordinance does indeed not sound right.

Jonathan Zwickel’s podcast Let the Kids Dance, about the Teen Dance Ordinance, produced with KUOW, will be released in early 2024.