Music venues in Los Angeles are the birthplaces of scenes, not just in the city, but across the globe. Landmark nightclubs like the Troubadour and the Whisky a Go Go are known as the nascent places where folk, psychedelic, and hard rock music began defining itself and building a groundswell. But there is perhaps no other venue in Los Angeles whose influence is felt as far and wide, and long, as the Park Plaza Hotel. In its storied existence, this historic location has hosted the first Beastie Boys gig in Los Angeles, had Basquiat behind the decks and Andy Warhol as a frequenter. The Park Plaza boasted Jane’s Addiction as its house band and both Lenny Kravitz and Little Richard among its attendees. It was the breeding ground for underground electronic music, which now has morphed into a multi-billion dollar business.

I first set foot into the Park Plaza Hotel as a 19-year-old. It was 1988, over half a century after the building’s grand opening, and two decades after changing ownership and rebranding as the Park Plaza Hotel. I was deep in my rock-chick phase, spending my weekends stomping up and down the Sunset Strip in my bra top, miniskirt, fishnets, and five-inch-heel pumps, my hair teased and hair sprayed to the heavens. My aesthetic was metal Dolly, but my affinity was death metal. This is why I was at the doors of the Park Plaza, where thrash metal band Death Angel was on the lineup at the venue’s legendary club night, Scream.

At this point in time, I lived on the Westside of Los Angeles. Bar the occasional foray to one-off events, the furthest venue I frequented was the aforementioned Whisky a Go Go in West Hollywood. I didn’t drive. The Park Plaza was so far removed from my regular haunts, it might as well have been on the moon. I didn’t know where I was in the vast sprawl of the city.

It’s impossible to go past L.A.’s MacArthur Park without having Donna Summer’s version of the titular song playing in your head. “Someone left the cake out in the rain,” your internal sound system sings as you gaze at the gently sloping grass banks—“sweet green icing flowing down”— to the park’s glittering lake, which is circled with the city’s signature palm trees. “I don’t think I can take it,” blares in your mind as you take in the backdrop of DTLA’s familiar skyline, its countless windows reflecting the Southern California sunshine. “’Cause it took so long to bake it/And I’ll never have that recipe again”—the song comes to its most sing-along-able moment when you spy an imposing structure on the other side of the park, the Park Plaza Hotel.

Breathtaking was the intention of the building’s original visionaries, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. The location started in the 1920s as the charitable organization’s Elks Lodge No. 99. Leaning into Grecian and Assyrian styles, it stands over 156 feet tall. The public spaces of the building are in keeping with its size. They boast 40- and 55-foot-high ceilings and expansive rooms, one of which tops 10,000 square feet. In addition to performance halls, the “monumental edifice,” as the Los Angeles Times called the building, also featured a gym and recreational facilities, private dining rooms, pool, and scenic rooftop gardens, as well as 175 guest rooms.

The building looks like it is from another time. It takes up half the block. Columns and arches run at least two stories tall and chase each other around the exterior. They rise higher at the building’s corners, with the highest arch marking the entrance. Numerous military friezes resembling the ancient figures in Persepolis are carved into the façade. Sculptures of soldiers hide in the arched windows, each one a little bit different than the one next to it. Angel carvings line up like sentinels, a quartet of them on each side of the structure, another two flanking the dramatic door. The building’s art deco aesthetic has the central section reaching for the sky. The effect is breathtaking.

By the mid-‘80s, MacArthur Park had become a hub for drugs, gangs, and prostitution. It was exceptionally sketchy at nighttime. My running mate Sheryl—similarly big-haired and looking like a Playboy bunny—and I were scared to park her car. We were mentally prepared to come back to find the windows smashed and the vehicle burgled.

As we made our way to the Park Plaza, we avoided eye contact with the many vagrants hiding in the shadows. We stood out among the seedy elements in the area, but even more so from the cool, pale-skinned goths and trashy glam rockers that were Scream regulars. They strolled up to the Park Plaza in their all-black attire, silver multi-buckled boots, and flat hair. Their casual attitude of belonging made us feel even more out of place.

Once we stepped inside the tall glass doors, we were in such awe, Sheryl and I forgot to fake nonchalance. The hand-painted ceiling was so high. The grand staircase was so stately. The beautifully tiled floors spread in every direction. Every nook and cranny had ornate details. The chandelier was magnificent. It was all we could do to snap our dropped jaws shut. This was no sticky-floored, disinfectant-smelling rathole of a rock club. This was something out of a classic Hollywood movie.

Stumbling around, trying to look like we knew where we were going, we got tangled up in the velvet drapes, behind which a variety of mischief was being made. This was the lobby level, with a long room packed with clubgoers along one side. Up the stairs was an even bigger room, also filled to the brim, with a proper stage. The Elks designed this space to accommodate their organization’s many high-profile activities. Scream turned the Park Plaza into the darkest of underground clubs. It worked so well, it was like the building was made for it.

The Park Plaza was a later location for Scream, which began as a DJ night for one of the founders, “rock & roll spitfire” Dayle Gloria. “We were playing Siouxsie and the Banshees and Bauhaus, Dexys Midnight Runners’ ‘Come on Eileen’ then Led Zeppelin’s ‘Whole Lotta Love.’ We wanted a night where we could play the darker side of alternative.”

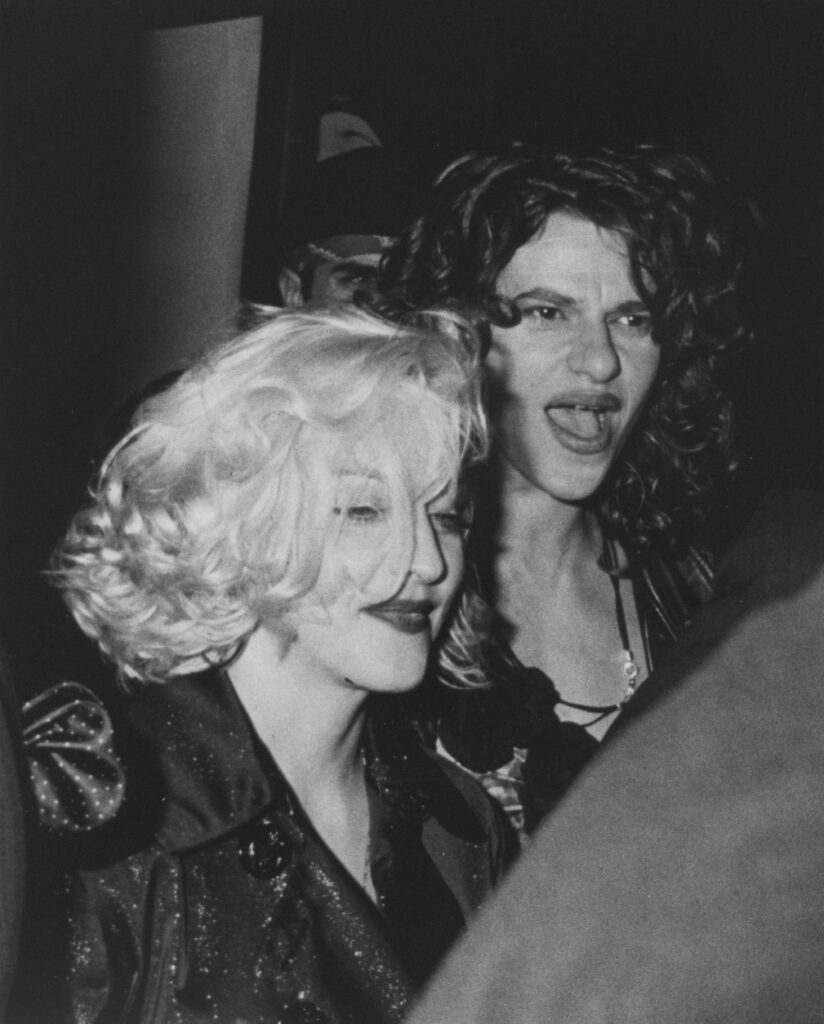

Gloria’s DJ sets, and those of her then-partner, Michael Stewart, drew the cool musician contingent. It was Taime Downe of Faster Pussycat, co-founder of the infamous Cathouse, who suggested having live music at Scream. Jane’s Addiction became the club’s house band. Scream—which took place at The Probe on Fridays and at the Park Plaza on Saturdays—soon became the place to play. It attracted local groups like Guns n’ Roses, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and X, as well as those from further afield such as Living Colour, Faith No More, and international acts like the Sugarcubes, Flesh for Lulu, and Balaam and the Angel, to name a few.

“The Park Plaza was so beautiful, they wouldn’t let us do half the shit we used to do at other places,” says Gloria, who had to curb Scream’s practice of customizing a venue to its own specifications. “But so many amazing things happened there. We had to bring our own lights and sound system—for all the rooms. We had a lot of projectors and projections on the wall. We built out the stage. One night, one of the guys in the band fell through but kept playing. We had lines around the block every single show. It stayed open until 4 a.m. so people that played on the [Sunset] Strip would come there afterwards. It was amazing.”

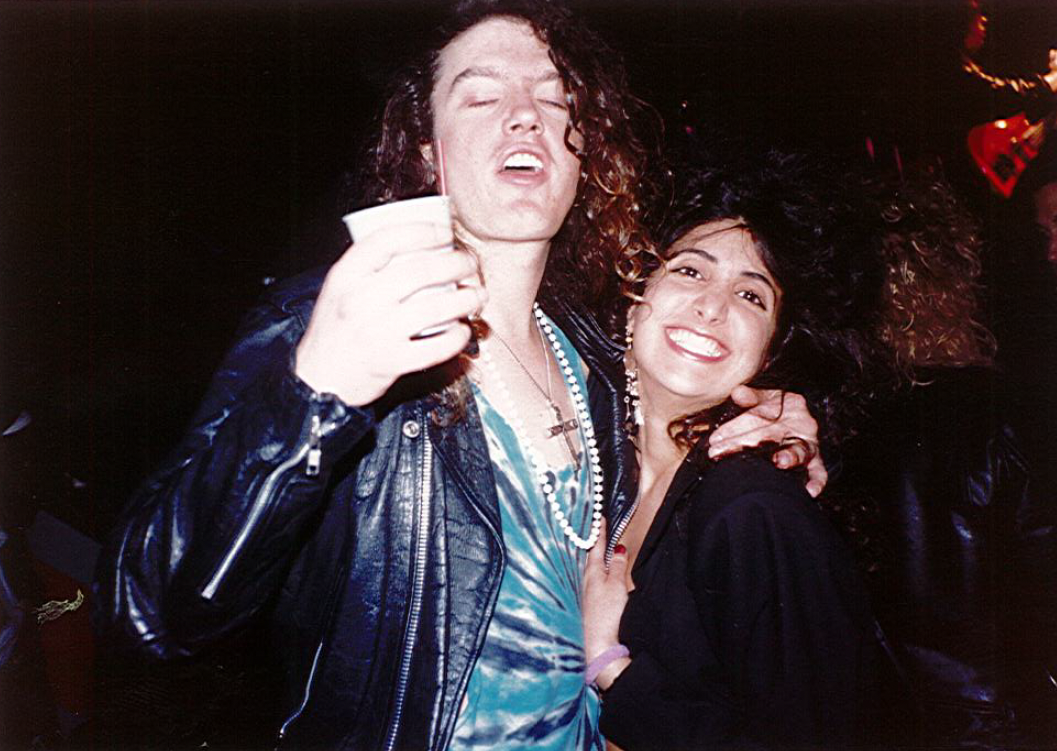

Scream attracted all sorts, including Little Richard and Lenny Kravitz, as well as musicians on regular rotation on MTV like Sebastian Bach. The club scene in Less Than Zero was filmed at Scream. This was a common occurrence at the Park Plaza, which has provided the location for many films and TV shows. Its singular interior is seen in Wild at Heart and Reservoir Dogs, Drive and Gangster Squad, as well as in videos for Steve Perry’s “Oh Sherrie,” Maroon 5’s “Sugar,” and Kendrick Lamar’s “Humble.”

Lyndsey Parker, music editor of Yahoo Entertainment, cut her clubbing teeth at Scream as a teenager. She remembers the first time she walked into the Park Plaza vividly. “It was like entering the gates of heaven,” says Parker, who became aware of the club through its listings ad in the LA Weekly. “The same sensation would happen when we made our way up those beautiful stairs and then again when the bands played. It was my favorite place. We had a limo for the night I went to my prom, which meant we could drive anywhere. I directed the limo to take me to Scream to see T.S.O.L.”

Before the next wave of rock music was being incubated at Scream, the Park Plaza was hosting Power Tools. Here, DJs played a combination of dance music from George Clinton to Tyrone Brunson, with a healthy dose of rock ‘n’ roll. Entirely unrelated to the radio mix show on L.A.’s Power 106 station some 10 years later, Power Tools was one of the city’s early clubs to play rap music. It also hosted the first Beastie Boys appearance in L.A., where they performed only two songs before the sound system blew up.

Power Tools pre-dated Scream at the Park Plaza Hotel by a couple of years. They shared a musical aesthetic to a certain degree, as well as a savvy crowd that appreciated an event with Malcolm McLaren as much as they did a Keith Haring show. The famed artist hand-painted Power Tools’ go-go dancers over the course of the evening. The club drew a mixed crowd that included Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Matt Dillon, John Cusack, and Robert Downey Jr.

Like Scream, Power Tools also brought in its own infrastructure every week, taking maximum advantage of the Park Plaza’s inherently beautiful structure and design. Jon Sidel, one of Power Tools’ organizers-turned-entertainment-entrepreneurs, says, “We used the building in as many ways as we could. We had four speakers at the corners of the dance floor and black lights. We had a guy from the ‘60s with elaborate, gigantic, psychedelic projections and slideshows.

“By 1986, we had a full arsenal of film projectors and hired a second person. We rented budget films or got them from the public library (before it burned down). We had theme nights, and our projectionists would make custom slides from the films to go with the themes. There is something about that location. We spent all week brainstorming what to do at the club. It was an amazing time.”

Too young for the Power Tools era, it bypassed me entirely. The next time I went to the Park Plaza Hotel was in 1991. On that occasion, I was dressed in baggy overalls and Dr. Martens, in search of the well-kept secret that was L.A’s underground rave scene—although I didn’t yet have the vocabulary for the music or the parties.

A couple of years prior, I had grown bored of the hair metal scene, which had become stale with identikit no-hope musicians living off generous strippers. I reverted to the British new wave music that soundtracked my mid-teenage years, which led me to electronic dance music in the early ‘90s.

In Los Angeles, this music was not conventionally promoted in local papers and radio stations. Instead, independent dance music record stores like Prime Cuts and Street Sounds were reliable sources for the music’s underground network. In the flier piles at those stores, I found Truth, which took place at the Park Plaza Hotel every other Saturday.

The Park Plaza neighborhood had become super shady since the ‘80s. But when we were inside, the world outside didn’t exist. So much had changed since my first experience here. My mother had passed away. Her absence was palpable, and the pain of losing her was chronic. Disappearing into the music was my way of grieving her.

The crowd at Truth included a significant number of British people, which added to the already British-leaning feel of the night. It gave an authenticity to the rave experience I was seeking, which wasn’t the house vibe of a Chicago warehouse or the garage sounds of a New York club. This is most likely attributed to one of the organizers, Steve Levy, a British expat. Levy attended famed U.K. clubs like Spectrum—and was mentored by that club’s promoter, Ian St. Paul. The DJs were also English. In fact, one of them, Mark Lewis, grew up on the same South London council estate as Paul Oakenfold, Carl Cox, and the Dub Pistols’ Barry Ashworth.

A student at Pepperdine University, Levy was promoting parties around Los Angeles, most of them on the Westside. He had gone to Power Tools and was reintroduced to the Park Plaza at the Batman premiere after-party in 1989.

“Truth was where rave was properly introduced to L.A. clubbers,” Levy told me in 2021 for the Faith Fanzine story. “…First-timers dressed to impress in Armani and Alaïa, then the next week they would show up in overalls and tank tops ready to sweat all night with their new raver friends. It was a great time.”

Truth ramped up quickly, reaching the space’s multi-room capacity of 2000-plus people within a few months. Again, the sound system had to be provided by the promoter. Like his predecessors, Levy also brought in projections, and weather balloons upon which the visuals were projected. He added lasers, which tripped the circuit breakers, but that wasn’t a deterrent.

“We hired a generator and ran power to the laser,” Levy says. “We had a bigger, full-color laser, but we had to get water to it to cool it down. We ran a firehose off the fire hydrant up the side of the building. We had a generator and a firehose so we could have this laser.”

For the promoters, their time at the Park Plaza stood them in good stead. Gloria booked a number of clubs including the Gaslight and the Viper Room. She gave the first gigs to bands like Weezer and Duff McKagan’s Loaded. Her unerring feel for spotting talent and new sounds remained steadfast, as did her no-nonsense attitude, which puts the most egotistical musician on check. From her first forays into nightlife, Gloria commanded a respect not given to women—a quality I admired from afar and strived to emulate. These days, Gloria is happily retired but willing to share stories when prodded. She also has a veritable treasure trove of Scream memorabilia—not to mention other clubs she’s been involved with— that would be the envy of any collector.

The Power Tools fellows, Sidel and his partner, the late Matt Dike, parlayed their music and business acumen into individually successful ventures. The latter established the independent record label Delicious Vinyl, which had significant success with its flagship artists, Tone Loc and Young MC. The Dust Brothers—who had production credits on the aforementioned artists’ albums, were connected to the Beastie Boys through Dike and ended up co-writing and co-producing Paul’s Boutique with Dike in his home studio.

Sidel went on to open several L.A. destination bars and had a long run in various A&R positions at Geffen, Interscope, V2, and, more recently, Position Music.

Levy co-founded Moonshine Music, a globally recognized independent electronic dance music label—the first of its kind on the West Coast. Moonshine cornered the market on compilation CDs, as well as launching the careers of a cross-section of artists including the chart-topping and Grammy-winning Dave Audé. Levy then moved to head of marketing at Insomniac and, later, Virgin’s festival arm. Currently, he is the CEO of Clanger Digital consulting for live events and entertainment-focused media and technology businesses.

In 2015, Curbed Los Angeles announced that the Park Plaza Hotel—which had been closed to the public and only used for private events and film shoots—was being renovated and redeveloped. The owners of the Hollywood Roosevelt–another historic Los Angeles hotel, whose refresh has brought back the original glamor and upgraded it with beautiful detail–partnered with the owners of the Park Plaza Hotel for this update and retrofit. In 2019, Curbed Los Angeles teased the public reopening of the space, renamed The MacArthur, in 2020, which has yet to happen.

I drove past the Park Plaza Hotel a week ago. It was boarded up and tagged with a jumble of careless scribbles. Homeless people lined the entire front sidewalk. MacArthur Park is also closed for renovation.

The liveliest spots around here are the Department of Public Social Services, and the makeshift stalls set up across the park with folding tables and collapsible marquees selling wares from used-looking plastic toys to foreign snacks. The hotel’s setting works against the Park Plaza ever achieving the level up the Hollywood Roosevelt is experiencing.

Still, the surge of emotions I experience as I approach the iconic building is overwhelming. The images of its glorious lobby, elegant ballrooms, and even its horror film hotel room hallways are emblazoned in my mind. The cacophony of different era-defining songs that play mashup-style in my head is deafening. No matter its fate, the impact of the Park Plaza Hotel is indelible.