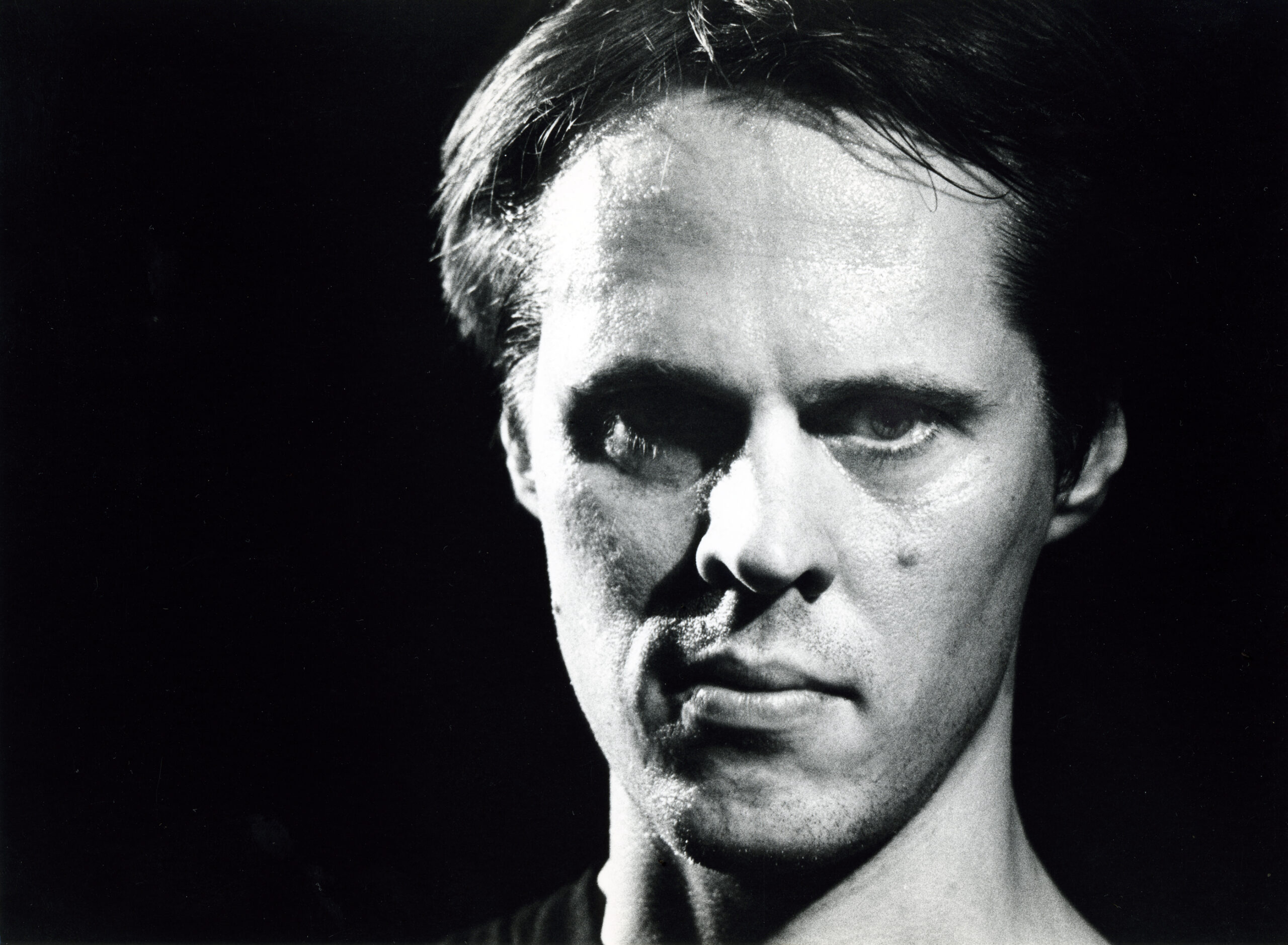

Tom Verlaine, the inimitable guitarist, punk iconoclast, and Television frontman who died on Saturday (Jan. 28) at 73, knew how to make a first impression. Television’s first album, 1977’s Marquee Moon, is a serious contender for the greatest rock debut of all time. Its odd fusion of pent-up punk urgency and intricate guitar interplay makes it a singular masterpiece, one you’ve surely heard if you’ve spent time in independent record stores or Lower East Side bars at any point during the past 45 years.

Yet the soft-spoken guitar legend produced far more great music beyond Marquee Moon and its more compact follow-up, 1978’s Adventure. In the rush to eulogize Verlaine, these Television classics have understandably absorbed most of the oxygen, while his solo albums have gone unremarked (an otherwise incisive New York Times obituary brushes past them in a single sentence). However, the man’s first five solo records deserve far more consideration, as they contain some of Verlaine’s most warped and far-out work.

When Television broke up for the first time in 1978, Verlaine immediately launched a solo career. His self-titled debut, released in 1979, picks up where Adventure left off. Half the tracks began life as unreleased Television songs, but the album also shows glints of a more playful side, from the Caribbean-flavored “Souvenir From a Dream” to the wacky Sprechgesang of “Yonki Time.” Meanwhile, “Kingdom Come,” a soaring call-and-response beauty, was immortalized when David Bowie covered it a year later on Scary Monsters.

Dreamtime, the 1981 follow-up, is an icy blast of staccato riffs and interlocking chords, with Verlaine’s strained tenor bringing order to the chaos on fan favorites like “There’s a Reason” and “Always.” (Tom Verlaine’s “Always”: not to be confused with Alvvays’ “Tom Verlaine”!) Though a modest seller, Dreamtime cracked the Billboard 200 and received the most acclaim of Verlaine’s solo career (it made the top 10 in the Pazz & Jop poll, and Robert Christgau hailed it as “Verlaine’s best batch of songs since Marquee Moon).”

While he enjoyed that success, Verlaine kept pushing into the unknown. As he promoted Dreamtime, he told an interviewer that the punk movement was dead and that he was “more into Coltrane and stuff like that than rock ’n’ roll.”

No wonder Verlaine’s third album, 1982’s Words From the Front, is his oddest and most experimental work. The beginning of his long collaboration with rhythm guitarist Jimmy Rip, it’s a truly eclectic creature that flits from the lush balladry of “Postcard from Waterloo” to jittery post-punk tantrums like “True Story” and the dubby “Clear It Away.” If Television is Verlaine’s Sex Pistols, this record is his Public Image Ltd.

Inspired by the Civil War Gen. Ambrose Burnside, the title track is a grim war epic that serves as a vehicle for some gnarled, expressive guitar solos. But the real hidden gem is “Days on the Mountain,” an astonishing post-Kraftwerk avant-synth groove that runs for nine minutes through a multitude of phases, with wobbly guitar tones that sound as though they’re bouncing off the surface of the moon. I’ve never heard anything else quite like it.

Verlaine retained the icy synths on 1984’s excellent, underrated Cover while veering back towards pop structures and traditional melodies. Highlights include the swooning pop of “O Foolish Heart” and the demented doo-wop of “Swim.” In a 1984 New York Times profile, he described how that album’s dreamlike tone was inspired by his subconscious mind: “Sometimes I hear melodies, rhythms and things in my dreams, really wild stuff that the conscious mind would never have come up with. I wake up and hum it into a tape recorder.”

Yet no Verlaine track feels more like a dream than “The Scientist Writes a Letter,” an epistolary masterpiece from his otherwise straight-ahead 1987 album Flash Light. Perhaps the most moving song Verlaine ever wrote, it’s told from the perspective of a scientist who’s consumed by his research in magnetic fields and writing to a lover (or ex-lover?) to say goodbye. “We men of science… you know,” Verlaine mumbles as the song dives into a mournful wail of a guitar solo. Verlaine was totally divested from ’80s rock trends, yet still making some of the most provocative music of his career.

His subsequent work was spottier. There’s 1990’s forgotten The Wonder, which flirts with a big-beat, funk-rock sound. It’s fun to hear Verlaine half-rap over grooves like “Kaleidescopin’” and “Shimmer,” but this is not his finest moment on record. 1992’s Warm and Cool was a collection of largely aimless instrumentals — hardly a disaster, but Verlaine was clearly saving his best material for Television’s surprise 1992 reunion LP, which drew contemporary raves. He was also involved as a producer in the early stages of Jeff Buckley’s 1997 sophomore album, on which songs like “Vancouver” and “Nightmares by the Sea” bear the unmistakeable influence of Television.

It’s worth noting that neither The Wonder, Warm and Cool, or Verlaine’s pair of 2006 comeback albums for Thrill Jockey (the solid Songs and Other Things and the instrumental Around) are available on streaming platforms, save for fan-uploaded YouTube rips. That’s telling of how desperately Verlaine’s solo works are in need of reappraisal or reissue.

While promoting Songs and Around in 2006, Verlaine gave the New York Times a rare interview. Despite having also told Billboard that Television had written “nearly seven” new songs, he admitted that he hadn’t been in the mood to record for many years, and seemed uninterested in his influence on contemporary bands like the Strokes (“It’s nice when people say nice things about you, but I don’t always know what they’re talking about”), and shrugged off the idea of touring full-time for a living. Asked how he’d sum up his life in a biography, Verlaine quipped: “Struggling not to have a professional career.”

Since then, save for the occasional Television reunion gig, Verlaine has lived a low-profile existence: no solo records, no social media, few interviews. In his songs, he was always drawn to the recluses and outsiders, those on the margins of existence. We men of science … you know.