As he did with his first electrified folk-style tunes almost 60 years ago, lately Bob Dylan has kick-started another pop culture trend subject to going awry: music artist-branded bourbons.

Spirits and song have been paired as far back as folks can remember: calyx cup and lyre, anyone? But it wasn’t until 2018 that stoner idol Dylan introduced his first bourbon for commercial consumption, Heaven’s Door. Opening up the pearly gates, soon singer-songwriters in rock, country, and R&B were dabbling in corn-mash liquors and kindred spirits. Of all the world’s whiskey—a word derived from the Gaelic for water (of life)— US-made bourbon has become today’s baddest beverage around.

For all you guitar- (and nit-) pickers out there, SPIN is well aware that American music tradition floats on old Scotch-Irish chanteys about whiskey in the jar—check out Metallica’s toilet-retching update (more about the band later).

Yes, alcoholic beverages have been a creative outlet and provided extra revenue streams for celebrities from Francis Coppola (vino) to George Clooney (tequila), and sure, Sammy Hagar was the first music maker to market white and brown spirits to his followers nearly a generation ago, but there’s something especially out-there about famous musicians now playing at bourbon for fans and profit.

Also Read

The Best Bob Dylan Documentaries

In case you’re not aware, by definition bourbon is an American whiskey—usually made in Kentucky. It must be distilled from at least 51% corn mash and stored in a new cask of charred oak, giving it a distinctive caramel finish—like corn syrup, not sugar in cola. Bourbon and Coke (or coke), the all-American cocktail!

To gauge the merits of music/artist-related maize elixirs, we turned to New York Times reporter/editor and bourbon expert/taster Clay Risen. Raised in Nashville, Tenn., he grew aware of neighboring Kentucky’s whiskey culture during one of its cyclical downturns around 2000.

“Today, bourbon is the most popular, coveted, talked-about spirit in America, but not long ago it was a liquor-store wallflower … Driving around Kentucky, I’d have to return to the same few distilleries open to visitors—not that there were many distilleries, period.” This, from the preface to Risen’s definitive spirits bible, Bourbon: The Story of Kentucky Whiskey (Ten Speed Press, 2021), a boxed two-volume set of prose and memorabilia. On Amazon, Risen’s words hold sway with 91% of responding customers giving his work a five-star rating.

I met Clay Risen off-duty, away from his day job writing Times obituaries, for a tasting of three musician-associated bourbons. He suggested an appropriate bar, The Whiskey Ward, named for when this part of New York’s Lower East Side was a cobblestoned parish of Irish and Eastern European immigrants finding solace in door-to-door taverns. Now the area is filled with boutiques, bodegas, and bagel joints. Our latter-day whiskey bar destination was an easy-to-miss old-style refuge behind a nondescript storefront.

Once seated at the table by the window, with a background din of downed drinks and loosened tongues, we enjoyed a few hours talking bourbon, history, journalism, and jive. To a habitual tequila drinker, the education in the complexities of corn whiskey blends was an eye-opener.

Before tasting, Risen filled us in on the origin of “bourbon,” which, like whatever else may be popular these days, can be controversial. Some trace it back to a distiller in Bourbon County, Ky., while others insist that it was named after barrels shipped down the Mississippi to New Orleans, ending up on Bourbon Street. He doesn’t buy either explanation.

“The theory I find most compelling is that [the] whole area was under French influence. It goes back to the Louisiana Purchase. Louisville, Ky. is a very French city, named after a French king,” says the author of three books on U.S. history.

He posits that bourbon was the result of early marketing in 19th century America: “This whiskey wasn’t aged, but the charred barrels added flavor to it. As it came down the river, it would get shaken in the barrels and take on color. They have clear liquors all called whiskey, so to separate this out they called it something different. Cognac was very popular then. It was imported from France and was a luxury. People who were trying to sell their brown whiskey came up with a French name that resonated with people buying cognac: ‘If we call it bourbon, they’ll think it tastes good, at a lower price.’”

Since it sparked our exploration, Bob Dylan’s Heaven’s Door Straight (aged minimum two years, without added flavors or color) Bourbon Whiskey ($49.99) was the first of the bottles we had poured by The Whiskey Ward’s top barman, Kenny, into appropriate glasses.

When Dylan’s brand was first introduced, the elusive bard announced in a prepared statement: “I’ve been traveling for decades, and I’ve been able to try some of the best whiskey spirits that the world has to offer. This is great whiskey.” A Nobel Literature laureate and thoughtful lyricist spouting such an endorsement for his own product sounded lame. He then added praise for his business partner, Marc Bushala, owner of the successful Angel’s Envy Bourbon. That Bushala recruited Dylan to participate in an entity called Spirits Investment Partnership (SIP), a liquor brand development company, made it sound more like crass commercialism than artistic expression.

Dylan’s only apparent contribution was the bottle, with a reproduction of one of his wrought-iron gate sculptures-–including wheels, chains, crossbars, and birds. Instead of inviting a bourbon bro or lady into amber paradise, it seemed more “beware all ye who enter.”

With lowered expectations, we began tasting.

Risen swirled the liquid in his whiskey glass and inhaled. “The nose starts off with a lot of apple. There are notes of nutmeg and cinnamon.” So far, so good.

Then an off-note. “There’s a ton of wood influence. It has an old hay smell. Something dusty about it!”

OMG, our bourbon expert could sniff out “terroir”—the earthy birthplace of an alcoholic beverage—decades before it was even conceived!

Flashback: The name of Dylan’s quaff came from a tune he recorded in 1973, “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” One of his simplest songs, with just two short verses, it evoked the impending death of a sheriff in the Old West. It was issued as a single and was a modest hit, yet it soon became one of his most recorded songs, by over 150 artists including Eric Clapton, Guns ‘N’ Roses, Jerry Garcia, Neil Young, Patti Smith, Paul Simon, Roger Waters, Warren Zevon, Cat Powers, Bono, Wyclef Jean, Television, Avril Lavigne, and Johnny Cash.

The song was part of the movie soundtrack Dylan had written for director Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, starring Kris Kristofferson—who secured a small acting role for his friend Bob. As luck would have it, this journalist visited the set of the movie when it was shot 50 years ago in Durango, Mexico. Was it dusty! There’s even a picture to prove it.

Usually wary of the media, Dylan ambled up and asked what the crew thought of his acting. The only possible answer: “Look, there’s Sam Peckinpah!” You couldn’t tell one of music’s Greatest of All Time he was a lousy actor. Though he’d never appear in a major fiction film again.

Back to Dylan’s bourbon. Clay Risen sipped and dissected. “There’s more apple flavor. Molasses. Brown sugar. A bit of fenugreek. A hint of dill.” This taster is also an avid chef—when not on deadline, he cooks often for his wife and two children in Brooklyn.

He didn’t look pleased with Dylan’s dram. “Overall, this is ponderous. Sharp. It doesn’t develop in the mouth. There’s a sugary tartness. It’s all up front.”

For the finale: how it went down. “The finish tastes like honey. But it dries out too quickly. There’s not much finish. It’s a little bit coppery at the end.”

When asked to rate it, on a scale from 1 to 10, no doubt somehow: “5.”

Of our sampling of three bottles, this bourbon will turn out to be at the bottom of the barrel.

Why just three, sent by their makers, for our session tonight? Because unlike a wine tasting, where you can spit out to keep sampling different bottles, the swallow is important to judging bourbon. At minimum 80 proof, drinking more than three bourbons and driving—not a good idea.

In fact, there is no standard way of conducting a bourbon tasting. We consulted with Kentucky-based Fred Minnick, organizer of bourbon-themed events for corporate captains and kings. “That’s why you need someone like me to set the format and the standards for judging,” he explained. Easily recognized by his trademark ascot, Fred is also a bourbon curator and co-creator of the Bourbon & Beyond drink and live music festival, which took place in Louisville recently after a two-year COVID suspension.

“There are no set rules for how to appreciate bourbon, unlike French Armagnac, say,” added this expert. For instance, he places less emphasis on aroma than his big city buddy Risen. Turns out they both started writing about bourbon around the same time and have become good friends over shared bottles. On Fred Minnick’s podcast last year, the two appeared as “Just Two Bourbon Authors Sipping,” exchanging observations about trends the way an earlier generation of freelance writers discussed the latest music.

For the bourbon critics, it seemed “like tryin’ to tell a stranger ‘bout rock and roll,” SPIN suggested, not far from where Lovin’ Spoonful lyricist John Sebastian had written those words. Risen nodded: “Bourbon is fun, but they must have had more fun writing about music in those days.” His favorite drink (neat; he’s not that into cocktails) has led to his own rock star encounters, like meeting country rocker Brad Paisley, who sounded savvier about bourbon than Dylan. “Bob Dylan’s people did it for him. Brad Paisley was very involved in the blending and the branding.”

Paisley’s passion shouldn’t come as a surprise; even for a country artist, he’s created more than his share of booze tunes. One of his biggest hits, “Whiskey Lullaby,” is a lament for a jilted good ol’ boy who “put that bottle to his head and pulled the trigger,” resulting in a sloppy demise, to be followed by his good ole gal’s. On the other hand, one of his wryest songs is a paean to “Alcohol”—“been making the bars lots of big money and helping white people dance.”

An industry insider told SPIN of Paisley being approached by spirits-makers in the past, but his management’s asking price for the use of his name was prohibitively high. Instead, the West Virginia-born country performer with an appreciation of good bourbon opted to work directly with a Kentucky distillery creating custom blends for over 30 brand-owners worldwide, Bardstown Bourbon Company.

Not even a pandemic could stop Paisley and his crew from the intoxicating task of blending corn and rye liquors to taste. Up to 10 people on a Zoom call would sample vials sent via FedEx and labeled by letter, commenting on the flavor. The final blend would include four bourbons aged up to 15 years.

“Bourbon is like songwriting; it’s a blend of things coming together to make something incredible,” Paisley was quoted as saying when he introduced American Highway in 2021. Then he ran off the road with a gimmick, as if required for every music-artist bourbon; here the Rolling Rickhouse, a cask-carrying 18-wheeler in which clear whiskey was turned into pothole-agitated amber pleasure. The youngest bourbons used in the blend traveled in barrels stored in a 53-foot semi-trailer truck that followed Paisley’s 2019 cross-country tour for 7,314 miles, through half of the 50 States. “These are really special barrels that saw more of the United States than most people I know,” Paisley added.

The accompanying press release was equally hangover-inducing: “The fluctuating climate of the barrels’ journey expanded and contracted their staves, imparting oak and char that cultivate the characteristic flavors of America’s native spirit.”

As Brad summed up: “It’s so similar to what goes into a great guitar. The right woods, the right craftsmanship, the right alchemy that makes this intangible, magical thing, and that’s what makes this so great to me.” Maybe Paisley should stick to writing country songs, not promotional copy.

For the final judgment on American Highway (list price $99.99), we turned to Risen. Our bourbon sherpa inhaled. “The nose is creamy. There’s a lot of corn in here. There’s caramel. It’s very esther-y. Like a fresh bread smell, with butter that’s very fresh.”

How would he compare it to Heaven’s Door? “It’s more complex than the Dylan bourbon. There’s a bit of vanilla. It’s a spritely whiskey and delicate, not like the wood notes in Dylan’s.”

Next, the taste: “It’s a little harsh, but I think that’s what they’re going for. It’s a younger corn whiskey with a more structured flavor.”

Does it taste of the highway, with a hint of tar or a soupcon of roadkill? Risen shrugged: “The Rolling Rickrack is fun. It’s clever. It’s a marketing thing. You don’t really taste the road. Overall, this bourbon has a buttery taste like buttered popcorn.”

As for American Highway’s finish: “It’s longer than Heaven’s Door. It’s a little hot for me, but what you would expect from a whiskey like this.”

Overall, he rated Paisley’s punch a 6.5, placing it above Dylan’s.

There was one more bottle to assess, Metallica’s Blackened (list price $39.99)—named for one of the thrashing band’s most apocalyptic songs. Want anxiety-filled lyrics? “Blackened” is a descent into nuclear winter with the world scorched into oblivion, recorded in 1988 yet relevant again with threats by a post-Communist war-monger named Putin.

First verse: “Blackened is the end; winter, it will send / Throwing all you see into obscurity / Death of Mother Earth, never her rebirth / Evolution’s end, never will it mend / Never.”

Risen was not deterred by the origins of this dark concoction (not technically a bourbon since it was finished in brandy casks). “I respect that Metallica was very involved in this. They had a personal relationship with the distiller, Dave Pickerell. He was the Johnny Appleseed of craft distilling. He’d been in charge of Maker’s Mark, which set a standard for quality. When he saw all these new distilleries popping up, he decided he could do as well. So he became a freelance adviser.”

Metallica members deferred to the legendary Pickerell’s solo formulation for their liquor’s flavor profile. He also came up with the seemingly obligatory rock star brand gimmick, in this case agitating filled casks using the Black Noise finishing process, blasting each batch with its own playlist of Metallica tunes; the band’s heavy low-frequency sound waves supposedly forced the liquid deeper into the barrel’s lining for more intense flavors, including burnt honey. The idea came from Pickerell’s years at West Point Military Academy, as a cadet and later a chemistry professor, where he was awed by the rumble of the campus chapel’s pipe organ.

Pickerell died soon after the introduction of Blackened in 2018. He was succeeded as Master Distiller & Blender by the esteemed Rob Dietrich. “A very cool guy,” Risen called him before trying this latest edition of Blackened.

“The nose is honey, very subtle with a real honey smell,” said our master taster. Could the Black Noise processing have something to do with it? “I don’t think rock music played through the wood matters.”

When it came to taste: “I like this very much. It’s very smooth, with honey and cinnamon, some fruit.”

The finish? “It’s long and very smooth. Complex, with brandy notes.”

All in all, Blackened was the best of the three rock star brands we tried. Risen’s rating: “7 ½!” (It was also the least expensive of our spirits at $40.)

But as good as it was, Blackened didn’t come close to top-shelf whiskeys. Even this bourbon newb could tell the difference when Whiskey Ward co-owner Joe Maritato sent over a bottle of his latest find, a small-batch blend that Risen rated a “9” and was obviously more complex than what we’d just tasted.

Risen noted: “All three rock star brands we tried are middle level. I wouldn’t stock them.” Maritato confirmed this by explaining there’s simply no demand for them, even Blackened. He’d never encountered a celebrity brand that would earn its place in his bar.

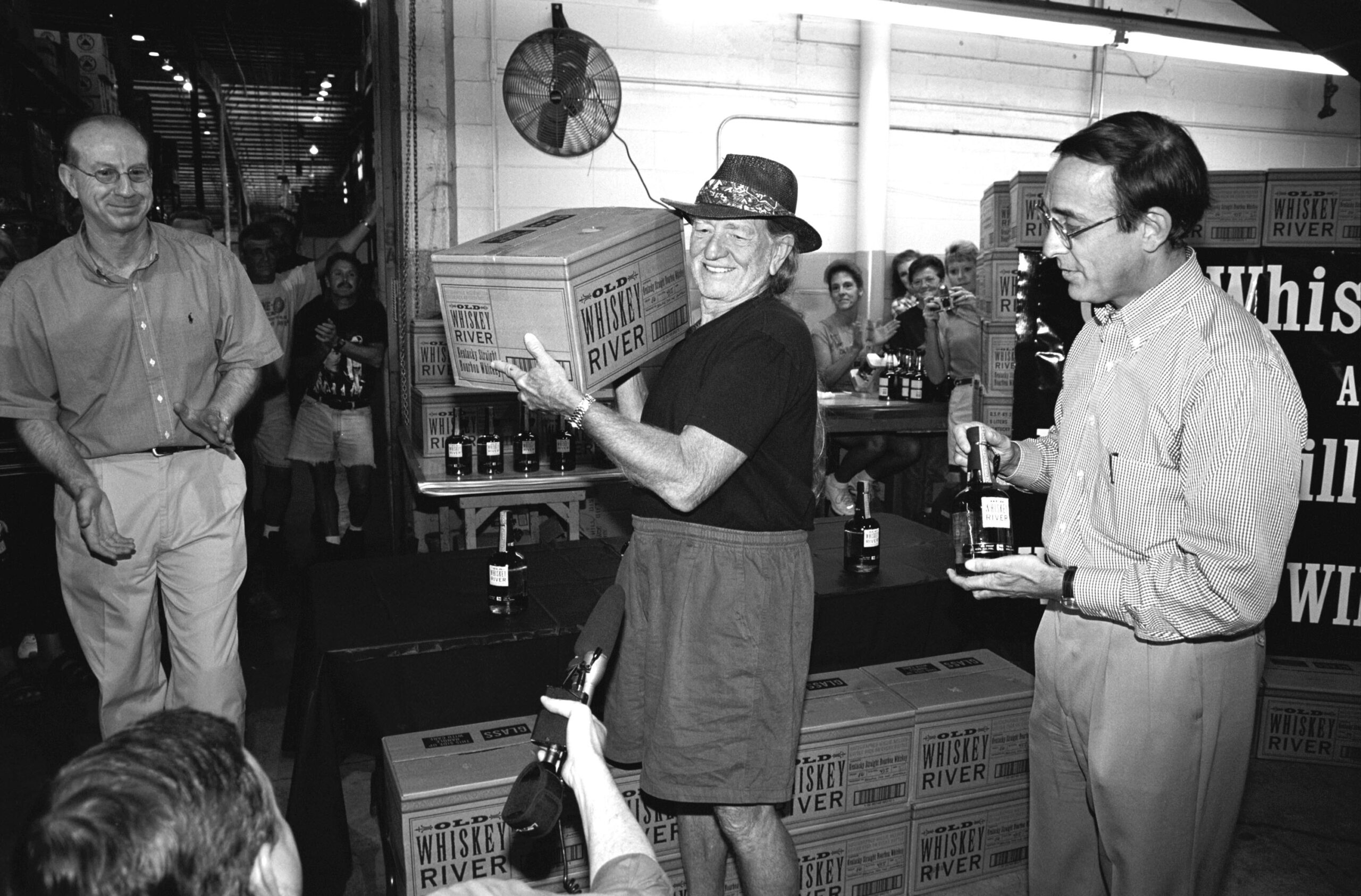

Maybe in a college town tavern or by a state line where influenceable drinkers congregate, rock star brands could be worth the space on a shelf. Otherwise, they’re not that desirable. Yet still, they come. At the recent Bourbon & Beyond festival, Kings of Leon announced their new lineup of a 19-year-old bourbon and two rye whiskeys. The Flaming Lips and GWAR can have their ryes, so why not The Pogues Irish Whiskey? Bourbon-wise (and dollar-foolish), there are Drake’s Virginia Black, Alice in Chains’ All Secrets Known, and of course, Old Whiskey River Willie Nelson Edition, the priciest of the lot, quoted as high as $1,999 a bottle online.

Ever since the current bourbon boom began, fueled early on by the Mad Men TV series, prices of rare batches have spiraled upward. So far, none has reached the heights of a cask of Scotch whiskey that sold for close to $20 million in a recent auction—at the equivalent of over $40,000 per bottle—but an upscale suburban liquor store in New York offers a bottle of Pappy Van Winkle 23-Year-Old in its original green glass container for $24,999. There’s even a thriving black market in emptied bottles of expensive bourbons resold with mediocre spirits inside.

At The Whiskey Ward, a one-ounce pour of the more recent Pappy Van Winkle Family Reserve 23-Year-Old goes for $150. Is it worth it? Co-owner Maritato was candid: “It’s an expense account or a celebration item. There are bourbons that are as good for a lot less.”

Final score:

Rock star bourbons: Meh.

Bourbon imbibing: Why not?