This article originally appeared in the July 1986 issue of SPIN.

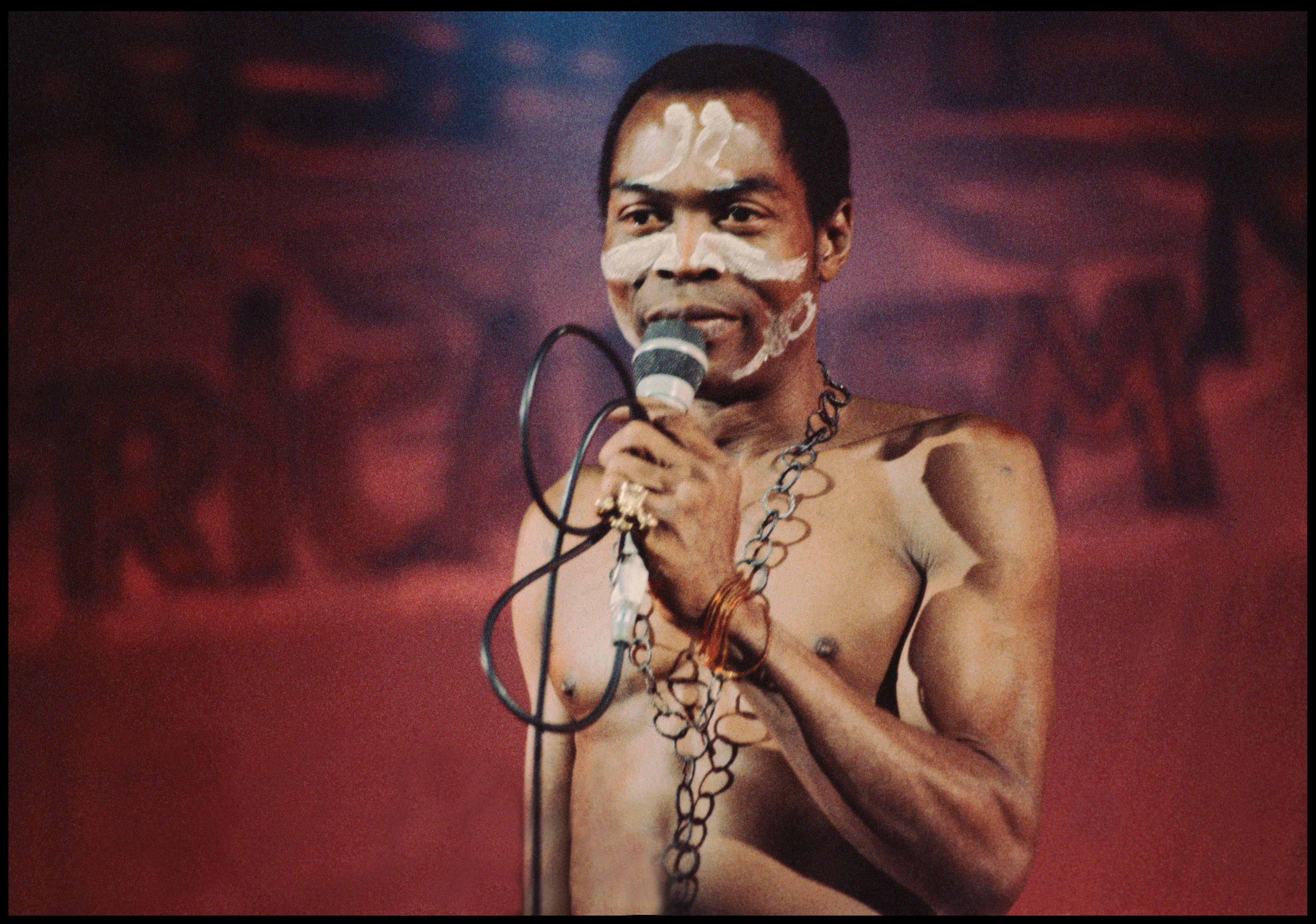

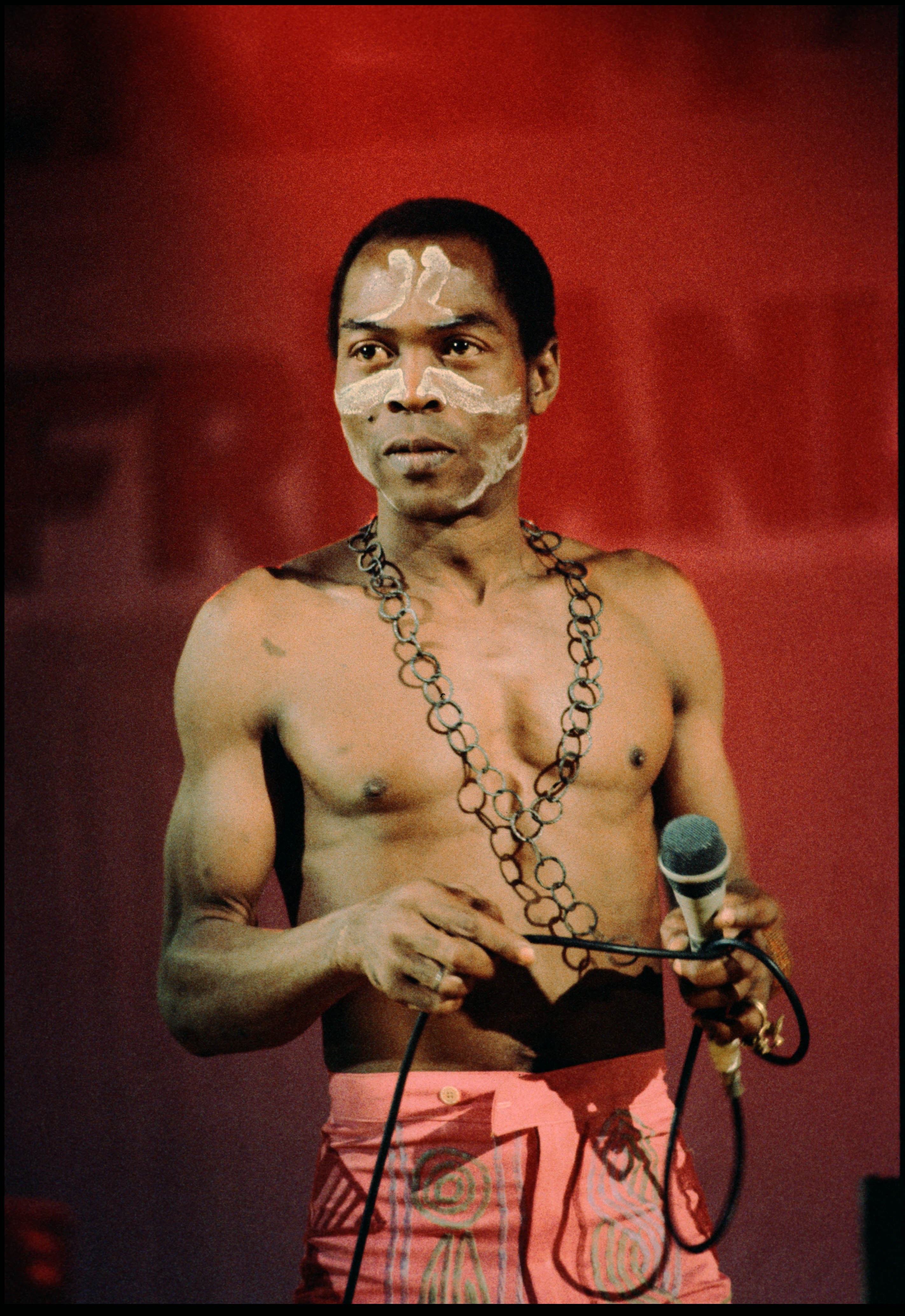

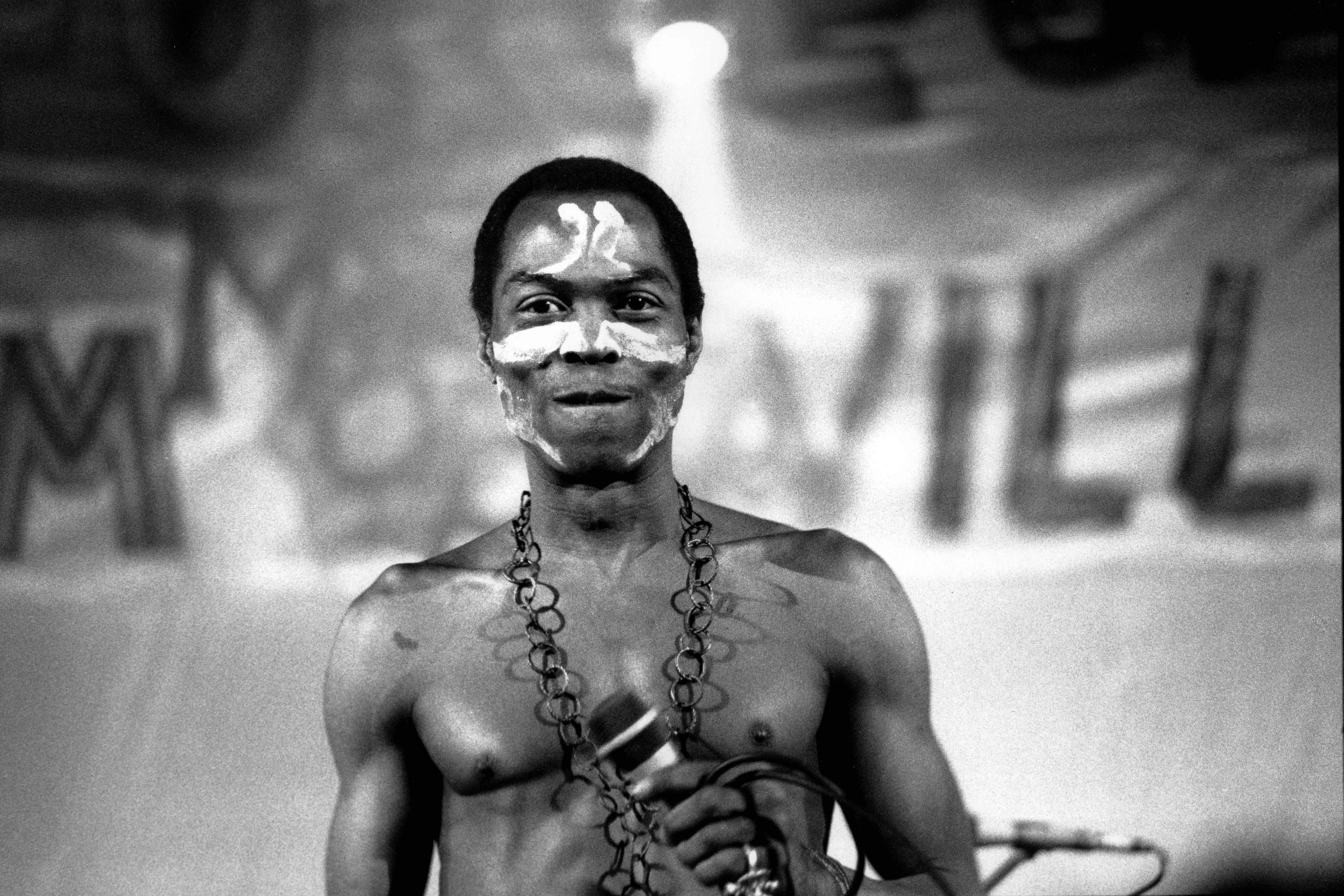

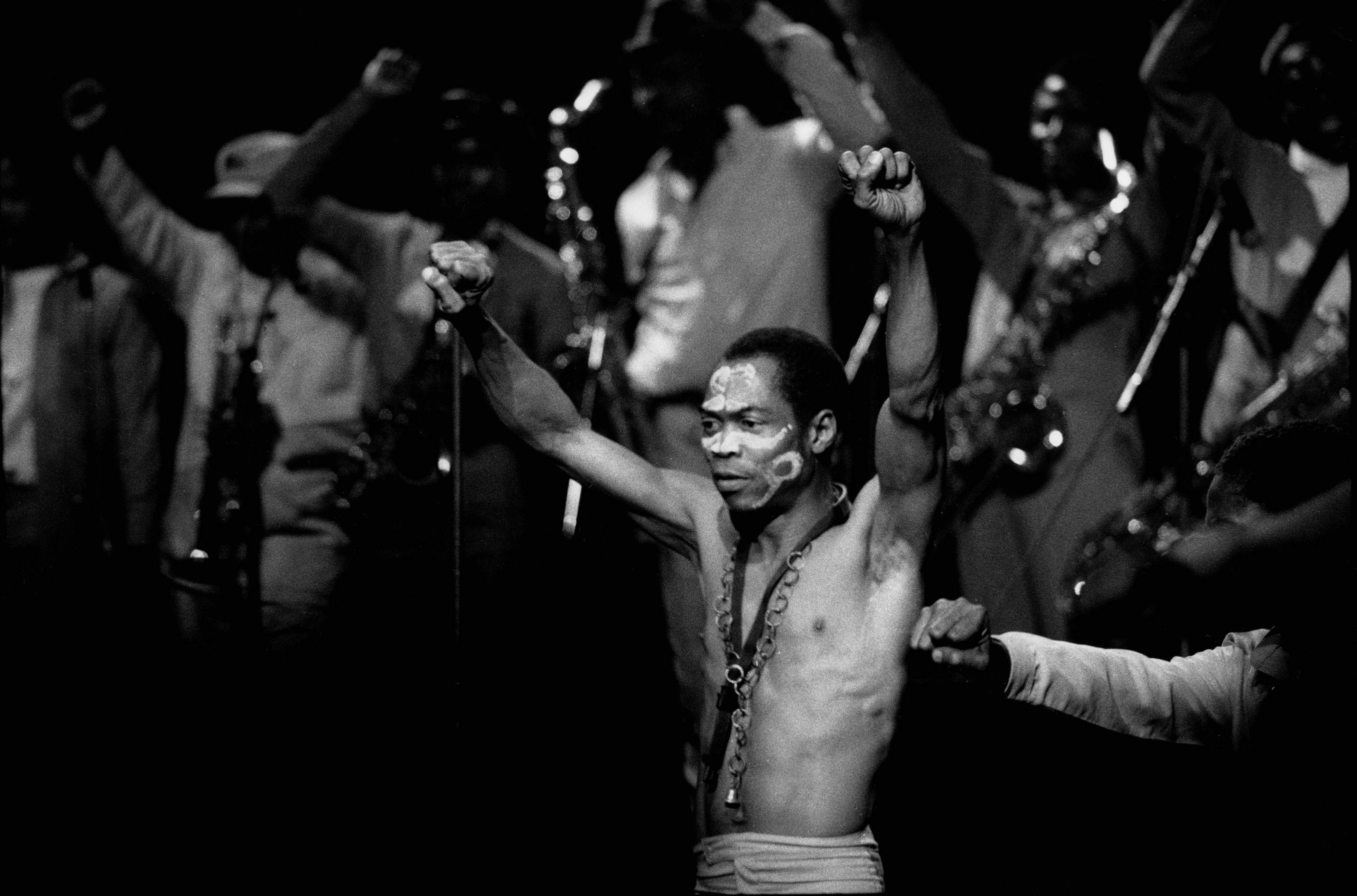

Nigeria’s Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, political gadfly, king of Afrobeat, and preeminent pan-Africanist, regained his freedom when Nigerian authorities ordered his unconditional release from prison on April 24, 1986, after he had served 18 months of a five-year sentence for alleged violations of currency regulation, which led to his trial under anti-subversion decrees.

His arrest on September 4, 1984, and subsequent conviction touched off an international protest campaign supported by such notable musicians as Herbie Hancock, David Byrne, Ginger Baker, Little Steven, and others who felt that Fela’s conviction stemmed from political pressure by Nigerian government officials.

After an enlightening visit to America in 1969, Fela singlehandedly brought the ’60s cultural revolution to Africa. Renaming his band Africa 70, he began recording a new sound—chopping, James Brown-style guitar funk, pulsating multi-percussion, chantlike vocals, an answering chorus of blaring horns, and lots of swirling horns and keyboard solos. His lyrics—sung in pidgin English or Yoruba, one of the languages of Nigeria—exposed and mocked corrupt politicians and civil servants, evildoers, and Europeanized Africans. These were not generalized protest songs; Fela named names.

For Fela, there was no distinction between public and private life. He turned his home in Lagos into Kalakuta Republic—a commune where his followers played music, smoked hemp, made love, raised children, and clashed with Nigeria’s military government. Worse yet, Fela intimated that he was considering running for president.

In 1977, one of Fela’s followers fled to the Kalakuta compound after a run-in with soldiers. The soldiers surrounded the house, and in the ensuing melee, they beat, raped and arrested Fela’s followers, ultimately setting the house on fire. Fela’s mother was thrown from a window and died soon after. Following the funeral, Fela carried her coffin, in a long procession of his 27 wives (members of his organization whom he married in a single ceremony shortly after the attack), musicians, and Africa 70 foot soldiers, directly to the military-barracks residence of then head of state Olusegun Obasanjo.

The encounter was demoralized on his Coffin for Head of State LP. The assault nearly destroyed Fela as a musician (his arm was permanently injured, preventing him from playing tenor saxophone), political force, and emerging star on the world scene. No musician has more completely lived his political beliefs or paid more dues.

Just as Bob Marley’s death heightened his recognition, Fela’s imprisonment gave him fame beyond his previous cult-hero status in America and Europe. At Kirikiri, Nigeria’s toughest prison, where Fela was sent, the inmates give new prisoners a terrifying initiation of beatings, torture, and heavy manual labor. But as Fela arrived to begin his sentence, he was greeted with cheers in the prison yard and asked to sing. The other prisoners began clapping out the beat as Fela sang the defiant title song of his album Army Arrangement.

Since the early ’70s, Fela’s Afrobeat had been known to growing numbers of pan-Africanists, black liberationists, African music buffs, political progressives, and aficionados of ground-breaking music. But aside from a minor flurry with the 1977 release by Mercury Records of his antimilitary satire Zombie, Fela’s music received scant airplay in the US and little attention in the media.

When Sunny Adé’s quicksilver success suddenly accelerated interest in African sounds, the time seemed right for Fela to step forward. He’d finally completed a long regrouping process in the wake of the late-’70s attacks and signed his first international recording contract in years. Capitol/EMI released a new live LP and reissued Original Sufferhead and Black President. But, after he was arrested, EMI dropped Fela.

Fela’s 39-member Egypt 80 band, led by his son Femi on vocals and sax, carried on as best they could after the arrest. When Fela was detained at the airport, he told them to fly on to America and play the arranged concert dates. He hoped that the seemingly absurd charges would be cleared up quickly. He was not released, however, and the band played disorganized, lackluster dates in California and New York before returning to Nigeria, where with the help of Fela’s brother Beko (himself jailed after he organized his fellow doctors), they struggled to support themselves by playing college concerts and shows at Fela’s club, the Shrine.

At first, Fela’s supporters were optimistic that he would be released after a face-saving interval, but concern mounted as months passed. Amnesty International launched an investigation into Fela’s case and declared him a political prisoner on October 16, 1985. MTV, PBS, the BBC, and other major television networks ran features on Fela, as did most major print media including SPIN (“Rebel on Ice,” May 1985) and The New York Times.

A petition campaign began, “Free Fela” T-shirts appeared, and large benefit concerts took place in Greece, Paris, and Berlin. A new deal with Celluloid Records launched the scathing Army Arrangement LP, Fela’s first new international studio release in four years, as well as reissues of such classics as Zombie, Shuffering and Shmiling, and No Agreement. Fela’s name and music reached millions who had never previously heard of him.

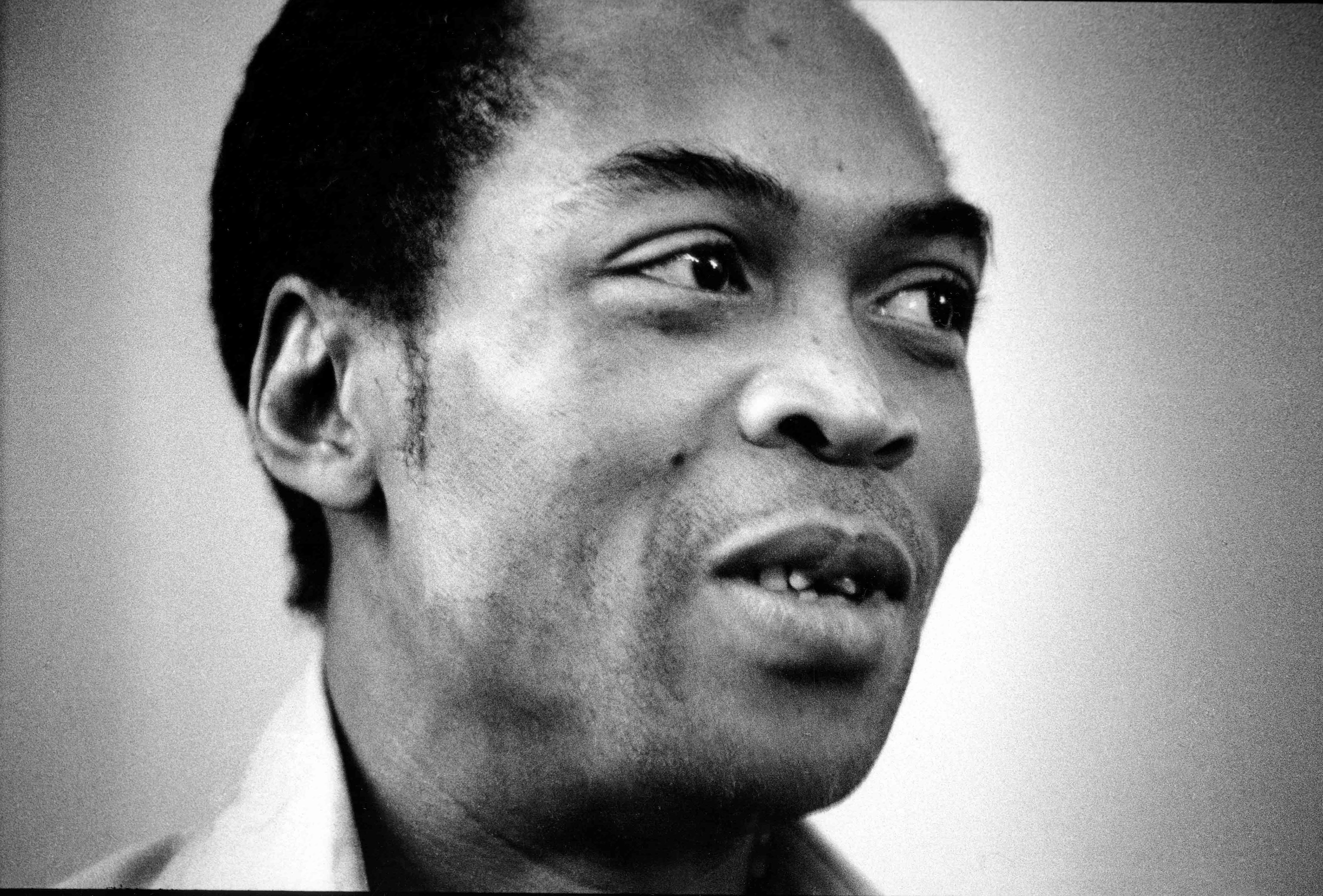

His release, granted by a Nigerian regime that publicly criticized the previous regime as having “gone too far,” poses some interesting questions: Will Fela temper his political activities or message? Has prison dealt a crippling blow to his psyche or to his organization? Will Fela’s music retain its power? We reached him in Lagos via a murky telephone connection amid preparations for his appearance at the Amnesty International benefit concert. Though his words were hard to hear, their meaning was clear and uncompromising as ever.

Tell us about your arrest and trial.

I was supposed to go to the States for a tour, so I got some money to take with me. When I got to the airport, this guy stopped me and said I had some money in my coat. I didn’t know he was going to take it so serious—I thought he just wanted a bribe. Anyway, I was detained. I went to the court Friday. I got bail and went home that night.

A week later, I was rearrested by the police. When I got to the police station, the officer said I was a CIA agent, that was why I was going to America! I told this guy that if they ever told this to the CIA, they would take a day off for laughter! So I started laughing myself. Then I got mad. My lawyer got mad and wanted to report them to the inspector general of the police. The inspector ordered them to either release me immediately or charge me with something.

That was why they had to move the case away from the court where it was before and re-charge me. Then they revoked bail, and after that they went through a whole mess of what we call “justice.” Then they sentenced me to five years.

You’d been in prison before several times. How was this experience different?

Oh, it was real prison, man. I’d never stayed more than 30 days for any kind of grievance before. This was 18 months.

What were the conditions like?

Our prisons are very bad. When I was in Ikoyi prison, people were dying every day. They were carrying bodies out of the prison every day.

Dying from what? Beatings? Lack of food?

The hygiene is nil, no good food anywhere, medical care is nil—prisoners have to buy their own medicine. For instance, because of my health, I have to have a special diet, and my family had to send it to me since last November.

What sort of treatment did you have from the jailers?

Oh, most of them were friendly toward me. Most, not all.

Since there was strong political pressure to put you there, why were they friendly?

They are ordinary Africans. They suffer the same things we suffer. They just work for their pay. They don’t necessarily have to be hostile toward me, because they understand what I’m doing. They aren’t really against me.

Were you at one time moved to a prison hospital?

Not a prison hospital. I was moved to a university hospital because I was ill—I had an ulcer.

Some people thought at the time that they were preparing to release you and that’s why they moved you.

Nooo! Bullshit!

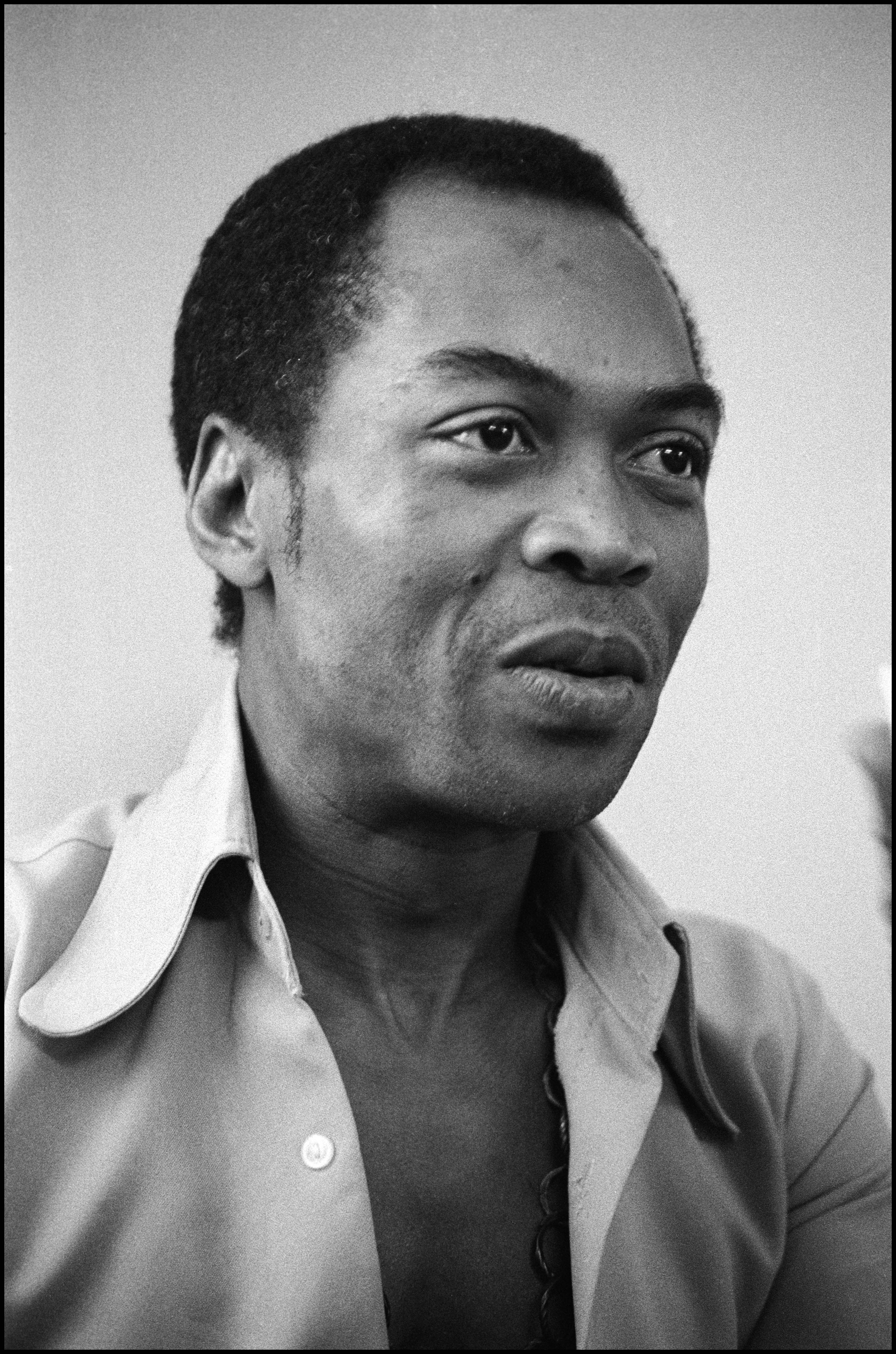

How did you deal with the situation psychologically and spiritually? What sorts of things did you do to keep your spirit alive and maintain yourself?

[Chuckles] When I was going to prison, I said to myself, “If these people want me to suffer, I must learn to suffer!” That was my first thought. When I got to jail, man, I saw that it was very boring. To kill boredom I had to either read books or play games.

Then I decided that these things only create an artificial interest. I decided to try to not play games, not read books, and just try to let the time go and see whether I could conquer boredom that way—try not to think, if possible, think only of the future, if possible, think of the past, then remix it toward the future. It was difficult at first, but things moved faster. I spent all day in bed—most of the day I’d sleep. Most of the time I’d wake up at night.

What was boring toward the end for me was the speculation that I was going to be released. This speculation went on for eight months, and made it harder. That was the worst. When it got too boring, I decided to expose this judge who sentenced me. It was the apology of this judge that quickened my release.

The judge who sentenced you came to you in prison?

He came to me, yes. And he told me that he didn’t jail me, that he was pressured, and that after the sentence, he wrote two letters asking for my release. And that I should leave everything to God!

[Chuckles] Anyway, I finally told the chief superintendent of prisons to try to write the present military government to release me if he felt that way, and he said he would do that.

I didn’t want to expose them at the beginning, because people were telling me to be bashful. But I’ve never been bashful all my life—that is mostly why I’ve been winning all my contests with the government. So I took up the strategy that I usually do. I wanted to expose them, but people said I was going to get out of prison [if I would] keep their “secret” secret. But unfortunately after eight months I was still there, so I called my brother in Lagos and told him to expose them in the press. I didn’t care about the consequences. After I exposed the judge, the whole nation started to rise against the government—the press, the people, everyone!

Do you think international opinion had any effect?

Oh yeah, it had a lot of effect. But I would like to suggest that those international movements like Amnesty…all these governments in Africa make their efforts almost fruitless. If the United Nations—it is supposed to be appointed to do these things—had a lot more power, that would be better.

International agitation over my case made people aware that the government was wrong, that is all. It was not effective in gaining my release. If I had not exposed the judge, I would not be out of prison yet.

What was the official explanation for your release?

It was an unconditional release. That means I have no record—I did not commit any offense.

What happened to your band and family when you were in prison?

That was when my brother Beko was very effective for me. He did everything for me, so my band is intact right now. It’s fantastic.

What kind of new musical plans do you have? Has your prison experience given you new ideas?

I had some new songs that I played in my head, but I wasn’t able to write them. So I’m ready to play them now. I’m going to add some new instruments and new effects.

What kind of instruments?

I don’t want to say until I’ve done it.

In the past, you have avoided synthesizers. What about now?

I don’t want to use electronics. I want to really control what the sound is like—I don’t want the machine to control what I say.

How do you see your role now? Do you see yourself making political statements? Will you sue the government for imprisoning you for no reason?

[Laughs sardonically] Look. How can I sue a government in a court that I have already said is corrupt?

But didn’t you sue them before?

Yes, many times. They didn’t pay me anything! So why should I do it again? It’s a waste of time. There isn’t any court. We just have people putting on wigs—that’s all we got here!

Will you continue making political statements in your music?

I will make a very final statement—what I think the government should do, what I think the country should do. I’m going to finish making those statements, and then I’m going back to work. I’m going to make my statement that I’m still going to run for president. The rest I can’t tell you until I say it in the open. I don’t want anyone to say I’m telephoning the CIA in secret [laughs].

Your manager said you don’t believe in marriage anymore, or that there is a change in your philosophy about lifestyle.

I didn’t say that. I said that I wasn’t going to allow the marriage institution to tie me down anymore. I said I’m going to play down my marriage, make my environment more open, because I want to have more women around me. Not only because I like women, but also because of my business, many women want to come around me.

The marriage I had several years ago [when he married 27 members of his organization at once] has made many African women who want to participate in my art stay away. This around me have used marriage to try to envelop my life—to make my environment inaccessible to other women. I have a new life now—don’t want anything to stop that freedom.

You see, modern African women use this concept of marriage as a license to kind of put a man in their pocket, do you understand? So [my wives] created a jealous ring around me. Women couldn’t speak to me. Women who aren’t married to me were being harassed, which was not at all in the African concept of married life.

You know, this is very colonial. The women are influenced by foreign lifestyles. They want to make marriage possessive, which I did not expect to happen when I married them. So now I will do as I was doing before I was married, because I think it’s important for what I want to do.

Do people misunderstand your philosophy of marriage and women? There is always a sensational aspect to “Fela and his wives.”

Oh, yes! People thought I was trying to say that women had no say, no rights. I was not saying that. I was saying that women had a role, a duty. When they want to have a say in government—though in Africa they are not expected to do that—they are not discouraged. They can do what they want to do. I was saying that women have their own duties to perform with respect to men, that’s all. I was not saying that women should take a back seat. If a female wants to do a man’s job, no one will stop her from doing it, but women have duties to perform as mothers.

On the African scene now there are very few musicians who are politically relevant. The most popular seem to be the more party-oriented ones, like Sunny Adé.

No one in Nigeria likes to play political music now, because the political situation is very bad. Africa is not like Europe in any way at all. If I can go to jail for 18 months, think how long an ordinary musician would go. But people want to hear political music. There are a few boys trying to, but it is not an easy thing to do political music. If you do, they clamp you down. At one time I was to play Zaire, but I wasn’t allowed into the country at all.

Some might say that if you had been a little more subtle, a little more calculating, a little less outspoken, you would not have been so persecuted. Is there any sense in saying that?

Yes, there is sense, but there is also sense in just acting the way you feel, without compromising rather than acting not he concept of being afraid of being punished for one thing or another.

But you’ve paid a high price—your mother’s death, for instance—and you were taken off the scene for a long while, which must have made the government happy. Was it worth it?

I’m not your average politician. I believe in higher forces. I believe that suffering has a purpose. I cannot suffer like this for no reason. I’m not working for any selfish reason or ulterior motives; I’m working for the improvement of my fellow man. So I have nothing to fear. I suffered a lot, but I feel fine now. I’m happy for the suffering, because I believe it’s opened the eyes of many people.

I have accomplished so far two things: People finally know the honesty of my struggle and the potentially of my leadership. People now want to hear what I’m saying.