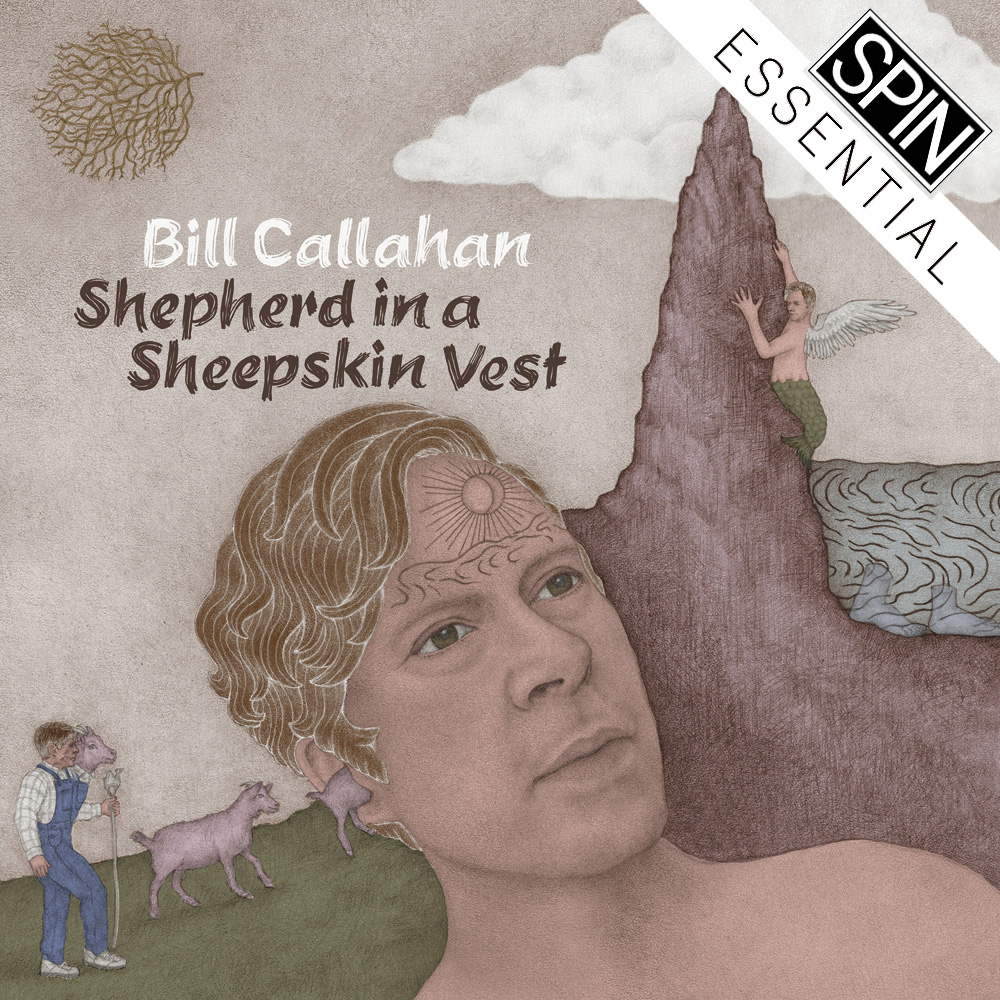

“It’s been such a long time,” Bill Callahan begins Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest by singing. “Why don’t you come on in?” It’s a sly literary acknowledgement of the six years that have passed since Dream River, his last proper album—a long time for a songwriter who usually appears with a record in hand every two years, as dependable as winter or the tides. The image of Callahan in an open doorway, welcoming you into his home and the album with a weary grin and an old pal’s embrace, also hints at the reason for his extended absence. He’s no longer the solitary wanderer he’s portrayed so memorably on many previous releases as Smog and under his own name, but a family man, with a new wife and son—a calling for which he briefly considered abandoning songwriting entirely. It’s a mercy for us that he didn’t.

Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest, a quietly joyous double album, is unmistakably a product of Callahan’s recent transformation. But it’s still a Bill Callahan record, meaning it treats family and domesticity not as unremarkable givens of a middle-aged and middle-class life, but as mysteries of near-religious significance. “Did you have that dream again, the black dog on the beach?” Callahan asks abruptly at the end of “Shepherd’s Welcome,” the brief opening track. His voice is sucked through a filter that makes it sound like a far-off radio broadcast, and the music evaporates behind him until a faint but portentous drone is the only thing left. It’s easy to imagine a psychoanalyst nodding sagely and remarking that the black dog is obviously a representation of death. A fixation on mortality and the passing of time gives Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest much of its thematic weight, as Callahan tempers each moment of gratitude for his contented current situation with the understanding that it won’t be like this forever.

The tensions inherent in “Shepherd’s Welcome” animate all of Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest, but the ominous studio trickery through which the song expresses them is uncharacteristic of the rest of the album. Elsewhere, the music is loose, amiable, and naturalistic. An ensemble of mostly acoustic instruments—guitar, percussion, upright bass, pedal steel, thumb piano, touches of synth and drum machine—chats back and forth like friends over coffee. After the first song, the production is almost entirely unadorned, capturing these voices the way they might have actually sounded in the room. Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest presents a particularly pristine and free-flowing variation on the stylistic idiom Callahan has been exploring since the final Smog record, 2005’s A River Ain’t Too Much to Love: derived somehow from folk and country, but obliquely, refracting the sensibilities of those genres across cubist landscapes that are difficult to compare directly to anything but other Bill Callahan albums.

Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest distinguishes itself in Callahan’s catalog not just by its subject matter, but also by the holism of its compositions. Paradoxically, they achieve their feeling of tossed-off informality through an astounding intricacy of form. Callahan has never been much for traditional verse-chorus structure, but here even more than usual, his words and music travel along the same unpredictable current. Together they map out the serpentine shapes of his thoughts, veering from anxious to devotional, morbid to hilarious, rarely ending in the same place they began. If it weren’t for the fact that the band reliably changes chords together, you might be convinced that Shepherd is a document of compositions that emerged from Callahan as he played them for the first time. This album does away with the elaborate edifices of recent records like Dream River and Sometimes I Wish We Were an Eagle, which provided Callahan’s voice with the same sort of isolation it enjoyed in the desolate lo-fi environs of the early Smog records, albeit through very different means. Now, the music is distinctly social, and occasionally spontaneous, like family life itself.

“I woke up on a 747, flying through some stock footage of heaven,” Callahan sings atop percolating arpeggios on the radiant “747,” following Dream River’s “Small Plane” with a trip on a very big one. “This is the light, bald and bold as baby crawling toward adulteration,” he continues, landing unexpectedly on that final word instead of something like adulthood, a reminder that growing older is a process of corruption as well as maturation. He ends on an optimistic note: “We turn darkness into morning / And we turn belief into evening.” The band responds in turn, kicking into double time, and the song reaches cruising altitude before disappearing behind a cloud.

Callahan exudes warmth and good humor across Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest. “I got the woman of my dreams / And an imitation Eames,” he sings at one point, a joke that might come off as mean-spirited if it weren’t delivered so earnestly. “I got married,” he intones, voice heavy with that Bill Callahan gravity, and waits a beat before deadpanning the exquisitely silly punchline: “to my wife.” “Let’s spend a lightyear together / Yes, I know it’s a distance,” he coos, and you can practically see that wife rolling her eyes. “Sometimes you sleep while I take us home / That’s when I know we really have a home,” he sang on “Small Plane.” Now, it feels like he’s finally arrived.

But Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest isn’t hermetically sealed in the living room. It also addresses the thrills and terrors of the outside world: ferocious beasts, sweeping canyons, a woman (“Angela”) who sounds like an ex or extramarital lover: “Like motel curtains, we never really met,” Callahan sings ruefully, conjuring both the scene of the liaison and its lack of true intimacy. It’s a big, ambitious record, with recurring images that resonate like cliffhangers across its hourlong runtime, appearing first in one song and resolving several songs later.

Callahan (or his label) seemed to sense that Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest would be a lot to take in at once, and released the first three sides of the as standalone collections on streaming services before dropping the whole double LP. The approach suggested that these sides can be taken as thematically connected suites as well as parts of a whole, and the material reinforces that reading. The second side in particular seems to chart the course of the entire album in miniature. Over the course of a few lines in “Young Icarus,” Callahan’s narrative zooms out from the mundane details of a road trip to briefly encompass the whole of human history. “From a hill behind a gas station in Scranton / I could see the old ways stretching out in their graves / And I thought but I didn’t say,” he sings, then switches to a dusky minor chord before saying what he thought: “Woman, ain’t it glorious / Without a past, there’d be no one here but us, lonely as Adam and Eve.” “So I left Eden,” he finishes, “with a song up my sleeve.”

Side two begins with birth and flight, in “747,” and lands in unknown territory. Its last song is “What Comes After Certainty,” whose spare and poignant lines could serve as a thesis for all of Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest, as Callahan has acknowledged: “True love is not magic, it’s certainty / And what comes after certainty.” Elsewhere in the album, the particulars of what comes after—friendship, comfort, aging, boredom, confusion, desire, unspeakable beauty, eventual darkness—are clear. But for now, they remain a mystery, happily unsolved.