Blood is smeared across bathroom mirrors, maybe from a nose punched by one of the violent drag queens vaulting around the gig on skyscraper stilettos. Makes me—makes everyone cramming the sinks—look blooded, like we’ve been fighting or hunting. Primal grunting comes from a toilet cubicle, the carnal occupation prompting men to pound its door, yelling, demanding to piss. Women circle in here, too, having given up on their own queued-to-panic restroom.

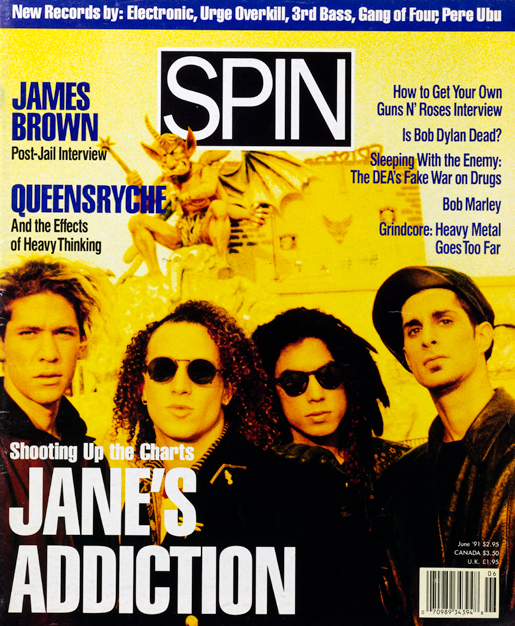

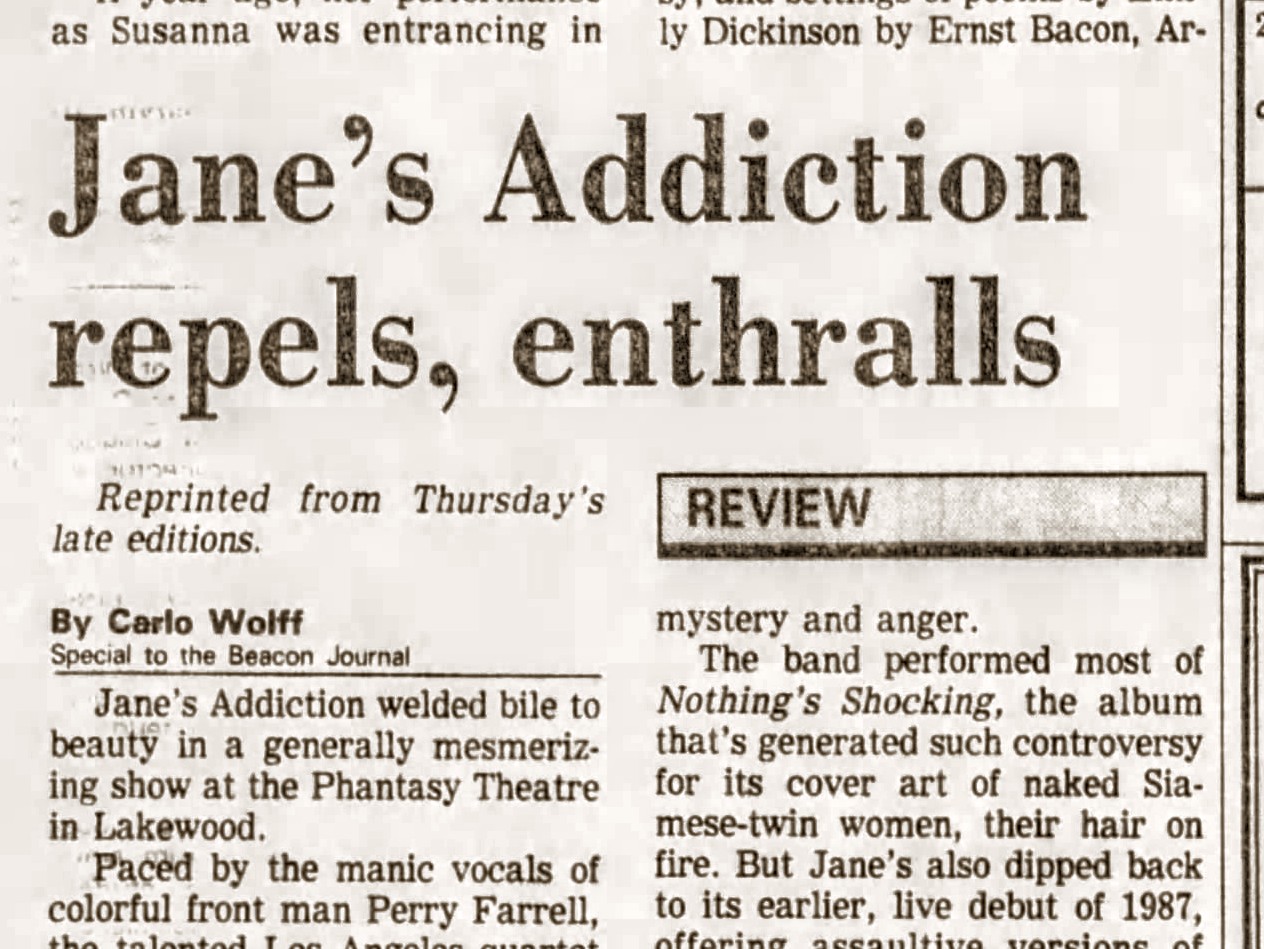

Striding out into the foyer where the churn and grind of Melbourne support act Killing Time leads back into the fray, I push past quivering clusters of teenagers drawn by the main event’s radio-friendly hit, “Been Caught Stealing,” but who clearly aren’t prepared for the deranging extremity of a Jane’s Addiction show in this Year of Our Perry, 1991.

It’s hard not to laugh at them, but it’s hard not to laugh at everything given the chemicals surging through me, and especially after I don a pair of diffraction spectacles which separate all points of light into prismatic sprays of color.

So some of the crowd have come to bop along to a hit they know, and the rest of us came to get nuked. When Jane’s Addiction finally appears and gets to work, the band caters to the latter with a motherfucking vengeance. The freaks and me may as well have been wired in a direct feed from the Marshalls, so pure and raw is the group’s transfer of madness.

Also Read

30 Overlooked 1994 Albums Turning 30

And Perry is raw and mad—no more the jostle and bounce of dreadlocks but instead shaven-headed and volatile in sleek Nazi leather—and enraged, lashing the assembled with “Yoooooooooooou donnnn’t faaaaaaaaaaaaaaahk-ing unnnnnnn-derrrrrrrrrrrr-stannnnnd!” and other strung-out lacerations of psycho-vitriol. He pisses on our fandom, and turns us against ourselves. His soaring, shredding wails coil time and sound upside down until Eric A’s basslines lift us over the line of threat and into the killing zone where Dave Navarro’s guitar detonates.

The atmosphere is severe, and the band argue on stage—full of rage, they snarl and hiss and even body check each other. Perry and Navarro look set to fight. And when the teenybopper’s alt-delight, “Been Caught Stealing,” is unleashed it is not as the cheeky, tight, familiar flight of radio fame but instead served up all punked out.

From there the night whirls wilder and harder, rushing and soaring and crashing the bloodied, drugged-up, crazed fanatics in a moshageddon that isn’t just blues-based riffing or boozed-out thrashing but instead the needleshot of a crystalline speed run. “Wish I was ocean size,” screams Farrell as Navarro marches his guitar through walls. A woman beside me is jacked to fuck by Stephen Perkins’ percussive onslaught in “Had a Dad,” and convulses, body twitching in a sea of sweat. She claws at punters, at her hair, at anything—only surfacing from the vicious fit to shriek with Farrell that “God. Is. DEAD!”

And when it is done, when it ends, with the band having receded back into the void, gone to wherever narco art-rock gods from L.A. disappear to after a set in Sydney, Australia, that woman, me, so many of us, stand dazed.

What has happened?

As time returns, and roadies gather debris from the abandoned, jettisoned stage, a feral queen in dirty feathered wings and a studded choker glances at me and me at her.

Why are we and so many others stunned—unable to move?

What the fuck happened?

Over the coming days and weeks I can’t settle. I feel either unwound or hyper-wound. I’ve witnessed—experienced—a Revelation without instructions: with neither Thou Shalts nor Thou Shalt Nots—a Revelation that threw me into a heaven of hell and then just … evaporated.

I get flashbacks. Dropping the needle on Nothing’s Shocking in particular, but also much of Ritual de lo Habitual and Jane’s Addiction, puts tingles down my spine and flips me into that space again—that exhilarated state of shock.

Then, towards the end of ’91, I read of the band in Honolulu playing its final show and breaking up. And so closes that rip in the world.

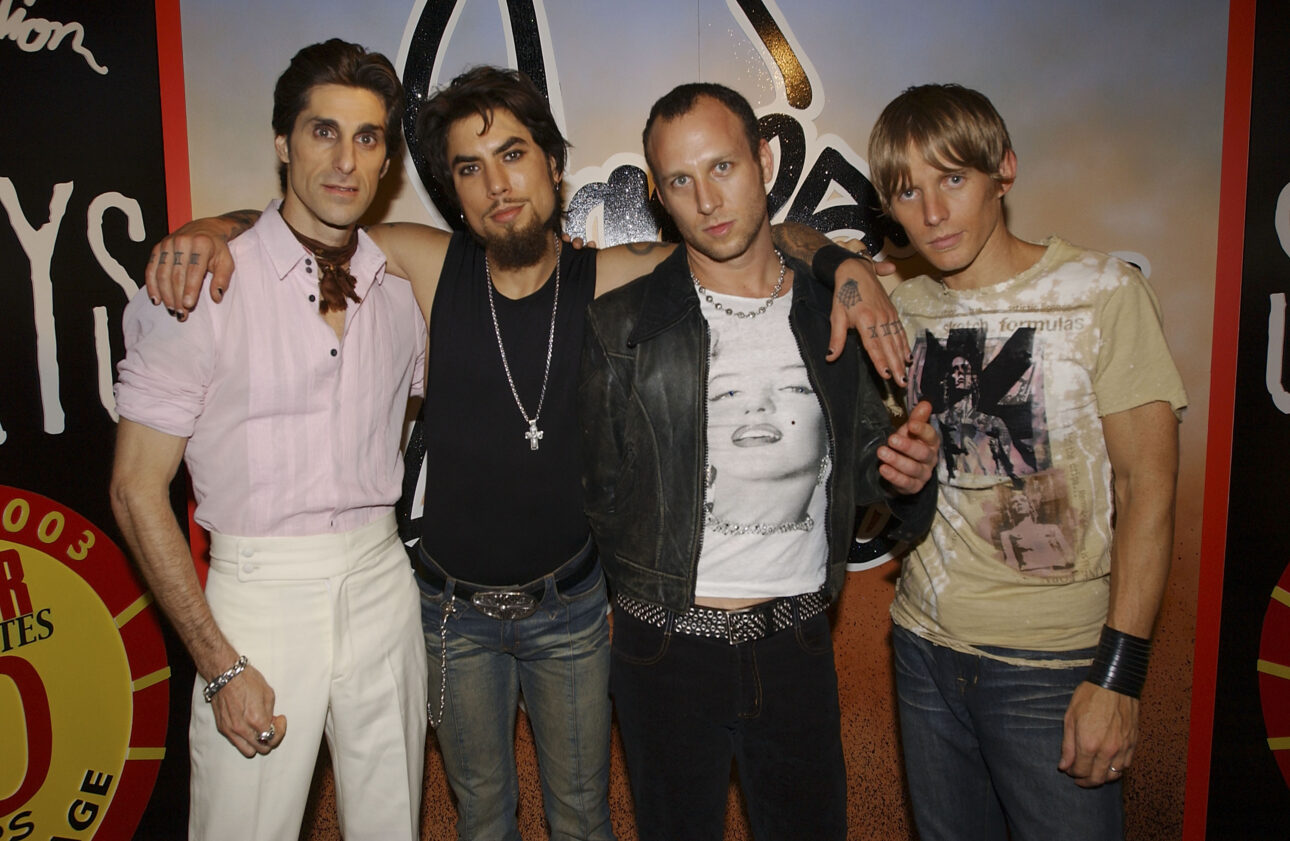

Twelve years later a band using the name Jane’s Addiction puts on a show at Sydney’s Enmore Theater. With the exception of the remarkable Eric Avery, who has been replaced by Alanis Morissette’s bassist, Chris Chaney, Perry and his troupe play themselves in this auto-cover band.

For that’s what it is: a vacuous simulacrum; a tribute band to, and of, its former self. The show tears no hole in time. The universe is not rent. There is no blood on the mirror. No one is left stunned. Instead of venom and fury, we get a performance that’s comfortable and competent—although nuevo-Perry’s habit of incessantly, visibly, beside-the-pointly fiddling with the effect board for his vocals kills any vestigial chance of us getting lost in the moment.

When the 2003 gig wraps up, my companions—none of whom experienced 1991—say it was a fun show. We then head off to listen to other music over drinks.

It’s clear, and has been throughout the continuing rehashes of Jane’s, that the drive, the instinkt, burnt out in ‘91. What has been parading ever since is a series of dead bands.

For rock to be fundamentally wild (rather than being primarily party music, which has its place but this is about art—and thus life—beyond the pleasure principle), then it must have at its core a seething, destabilized, and destabilizing reactor. If musicians burn out or go insane in the process, then so be it. Severity is to be respected. Wellness can go fuck itself. A seething core is what Jane’s had, what it was, in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. This is what makes the records explosive and what made the shows transfigurative. To continue playing the songs without that mongrel soul is just cash register stuff.

It’s kitsch. And before we argue about what ‘kitsch’ means, lemme paraphrase Princeton philosophy professor Alexander Nehamas: kitsch is art that does everything for the viewer except pay for it.

Substitute viewer for listener or concert-goer, and there we have it. Jane’s Addiction craves nothing any more. Porno for Pyros has no carnal flame. Compared to the mad days of their gestation there are no mysteries of shock and awe, no strut and spunk. Now we see costumes of youth donned by the old. There could have been new, mature work, but it takes a maturing of artistry, and some just can’t do it, or they can’t face the composer’s equivalent of Denis Johnson’s advice for would-be artists of the written word: write naked, write in blood, write in exile.

How satisfying it is when an artist works with their maturing, instead of in denial of it. As a positive example, the 69-year-old David Bowie comes to mind with Blackstar, released two days before his death in 2016. With this deathbed album, the suave freak redeemed himself for much of the dross he’d put out after his hitherto last excellent album, 1980’s Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps).

Turning back to rock, why is tapping the crazy vein so important? Rock may have harmonies but it is not about harmony. It is about the artful conjuring of chaos and what comes of chaos. I think of the Birthday Party’s late guitarist, Rowland S. Howard, describing Echo and the Bunnymen, Teardrop Explodes, and other shoe-gazers he saw in London as “bilge,” saying that rock instead needs to be dangerous; that it is an arena of confrontation; that when the Doors had lines of police separating the band from the crowd—so volatile were the shows—that is the gold standard for rock.

This is not about nostalgia—about missing my youth, or believing in good ol’ days. To be clear, I couldn’t agree more with a line from a Tony Hoagland poem that “nostalgia is the blank check issued to a weak mind.”

Fuck nostalgia. This is about magic and power. It’s about the sublime. And while chaos is fundamental to rock, other genres approach the sublime in other ways. At gigs in the years before that ‘91 Jane’s show, and over the decades since, then as a kid and now as a cantankerous bald fuck, I have witnessed, experienced, a small pantheon of artists touch the sublime in their performances. Who comes to mind? Lonnie Holley, Sheila Chandra, Bill Callahan, Diamanda Galas: straight-up.

All of these varied performers—and no doubt for you there are artists you’ve lost your shit to, or wept to right there in front of them—tapped a pristine essence on the nights I was lucky or determined enough to catch a show.

But we are here talking rock as an art form, and the essence of rock is chaos. Years back, when I asked Diamanda Galas what kind of rock she was into, she snarled that after Led Zeppelin, who gives a fuck? To her, Jimmy Page and co wielded the hammer of the gods. For me at Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion in 1991 it was Jane’s.

And what comes of this beautiful blasphemy? Why try to rip a hole in the universe?

Because catharsis. Because we need to be destroyed in order to live. Our vanity and pride and ego and fear block us and lock us into holding patterns of lives.

Mythologist Michael Meade speaks of how chaos was once considered a “divine primordial condition, or precondition, from which everything else appears.”

We snub chaos, or at least paste our fakery over its denial, at the cost of a fully lived life and at the cost of a fuller comprehension of being and unbeing. Denoting the anarchic force’s opposite as ‘cosmos’—the quality of ordering and harmony—Meade says that the cycling of these polarities make and unmake and create and devastate and recreate all. Their interplay is at work beneath “the skin of all existence,” and generates “the shape and motion of this world,” says Meade.

A line comes to mind from the cheery Tasmanian cannibal flick, Van Diemen’s Land: “If you have no scars, the crow will eat your eyes.”

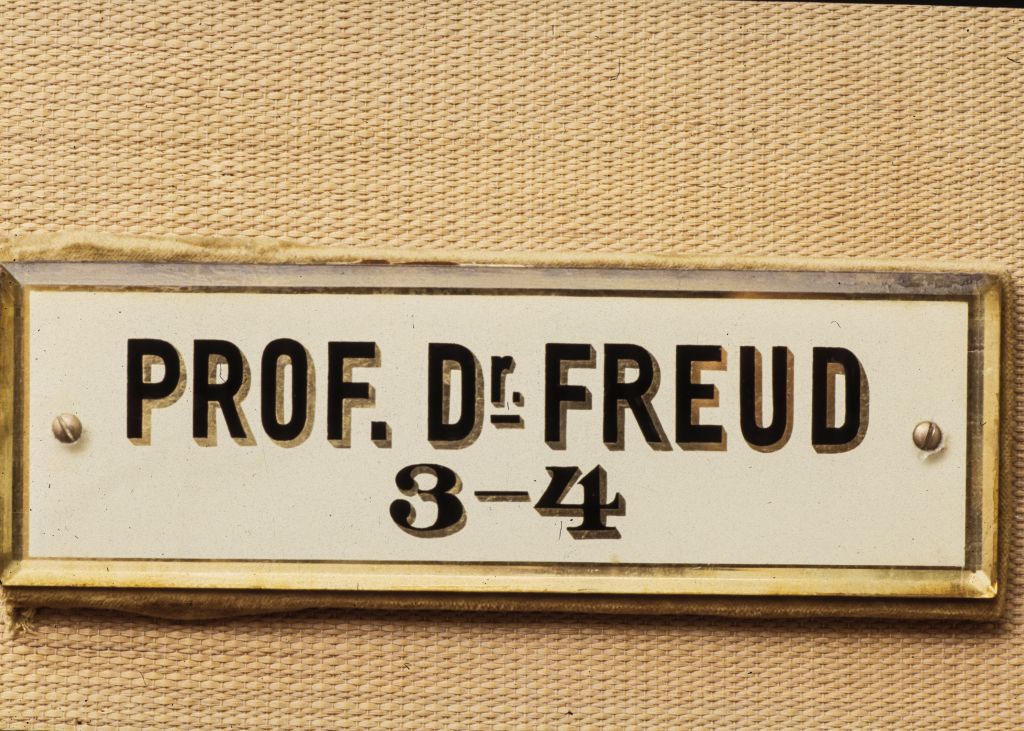

As in we need to be broken to have vision — to see not what we want, not our illusions about our sanctity and centrality, but the rugged reality of a vast and often vastly indifferent world. This is the world explored by Freud in Civilization and its Discontents, a mature piece of literature not far off being written naked, in blood, and from exile.

In it, Freud writes of a friend who sees at the heart of all religious inclinations a yearning for the “oceanic,” the sensation of being “limitless, unbounded.” Cranky old Sigmund said he cannot find such an impulse in himself, but I certainly have found it in me, and still can. And I believe this impulse to be a strong current in America’s vast death toll from intoxicants, from obliterants, running at more than 100,000 corpses per year (when the smack begins to flow … and all the dead bodies piled up in mounds … and I really don’t care anymore).

Freud argues that the gratifications of unchecked sexual and aggressive expression peak well beyond what civilization can allow if we are to live in peace and security — hence the need to sublimate our urges: to dim our fires and use their diluted fuels in creative and productive outlets which serve the greater good. The social contract, Freud argues, keeps anarchy at bay, but at the cost of explosive primal gratifications: “primitive man was better off in knowing no restrictions of instinct.”

Hence rock, where the less sublimated it is at heart, the more power it packs — the more likely it is to leave concert-goers standing stunned and wondering not what just happened but what to do tomorrow, how to live once a bunch of punk-ass musos has shockwaved us past the pre-gig horizon that shrank our oceans. That lined and limited our lust for life.

So Perry, thank you for 1991 but it was enough. It was everything. No need to play it again.