For those of us who live stateside and aren’t connoisseurs of mega-theatrical stadium pop, the song “Toy,” performed by a singer named Netta Barzilai, may be unfamiliar. It was the Israeli entrant and overall winner of last year’s Eurovision contest, the annual song competition between member countries of the European Broadcasting Union. And if you haven’t seen Barzilai’s Eurovision-winning performance of “Toy,” it’s really worth a watch.

Will this be the winning performance of #Eurovision?

Watch #TOY by @NettaBarzilai now!#ISR #VOTEISRAEL pic.twitter.com/PM721nkBe2— כאן (@kann) May 12, 2018

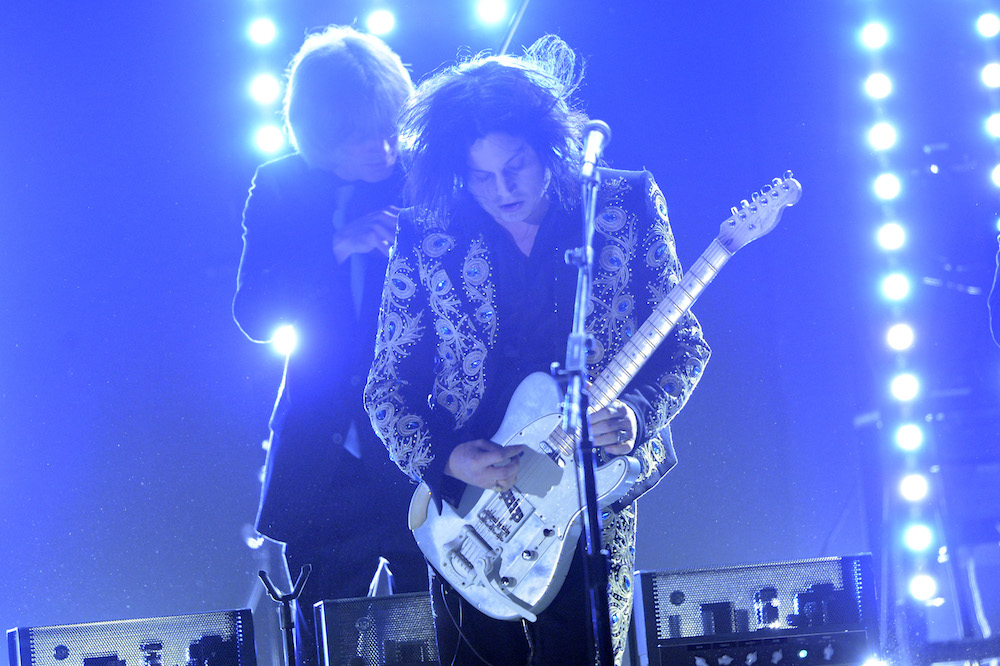

To me, “Toy”‘s most distinctive elements, by far, is the bizarre and utterly charming percussive sounds Barzilai makes with her mouth during the intro and at various points later in the song, which I can only describe as sounding like Missy Elliott doing an impression of the Bluth family’s various inept chicken dances in Arrested Development. But “Toy” made the news this week because of a different section, the chorus, which Universal Music Group believes bears a strong enough resemblance to the White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army” that Jack White should be retroactively added to the songwriting credits. Rather than fighting them on it and risking a lawsuit, “Toy” songwriters Doron Medalie and Stav Beger did as the label asked, thus entitling White—and, depending on the White Stripes’ arrangement with their label at the time, perhaps UMG itself—to some share of the “Toy” royalties.

You can judge for yourself whether “Toy” is a “Seven Nation Army” ripoff. The section in question starts at around 1:18, when Barzilai sings “I’m not your toy / You stupid boy,” through about 1:40, with a synthesizer repeating a similar melody. There’s some resemblance there, if you’ll indulge some brief music theory talk: both are in minor keys, with similarly syncopated rhythms, and melodies that that include a descending half-step between the sixth and fifth scale degrees. But “Toy” places most of its emphasis on a different descending half-step pattern, between the third and second scale degrees, which isn’t present in the famous “Seven Nation Army” riff at all. (To be fair, White does use it in the guitar solo.) As someone who has very little knowledge of contemporary Hebrew music, but happens to live in a neighborhood where it’s quite popular, the “Toy” melody seems to have as much in common with the curlicued melodies I hear coming out of shops and restaurants every day as it does with the White Stripes. It’s not hard to imagine the similarities to “Seven Nation Army” being purely coincidental.

UMG’s demand for songwriting credits in “Toy” is illustrative of a dynamic that has become common in the wake of the Marvin Gaye estate’s 2013 multimillion-dollar legal victory over Robin Thicke, Pharrell, and T.I. for supposed similarities between their “Blurred Lines” and Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up,” which a dissenting appeals court judge recently called a “devastating blow to future musicians and composers everywhere.” “The majority allows the Gayes to accomplish what no one has before: copyright a musical style,” Judge Jacqueline Nguyen continued—that is, to claim copyright based on intangible similarities rather than direct musical quotes.

Since then, artists like Ed Sheeran and the Chainsmokers have retroactively given over some credit for their own hits (to TLC and the Fray, in the case of those two) rather than face a potentially ugly and expensive court battles. As satisfying as it might feel to see Sheeran and the ‘smokers get some comeuppance, it really is a bad precedent, turning the time-honored creative strategy of drawing inspiration from past works into a punishable offense. Maybe, a decade from now, some young singer will find an old YouTube clip of “Toy” and be moved to create her own song based on the sound of an insane beatboxer at a poultry farm. She should be able to do that without worrying about getting sued.