The Neil Young Archives, a digital library released last week purporting to contain everything the legendary songwriter and guitarist ever recorded and released, is a tremendous resource for both longtime fans and anyone who’s curious about approaching his prodigious five-decade catalog for the first time. Young is notoriously finicky about the context and sound quality of his work, which disappeared without warning from the major streaming services for about a year before being reinstated just as suddenly in late 2016. It’s possible, maybe even likely, that he will wake up one day in the future and decide to cut off Spotify listeners once more, perhaps as chastisement for their failure to embrace Pono.

Here, then, is the entire unruly collection, from “The Sultan,” the 1963 debut single of his teenage band The Squires, to his 39th studio album The Visitor, also released last week. Everything is presented in master-quality audio, according to Young’s detailed specifications, in a format he’s not likely to discard on a whim, and it’s completely free if you’re willing to surrender your email address. It’s a treasure. But this is Neil Young we’re talking about, meaning it’s also a loopy, arcane mess whose organization defies all earthly logic.

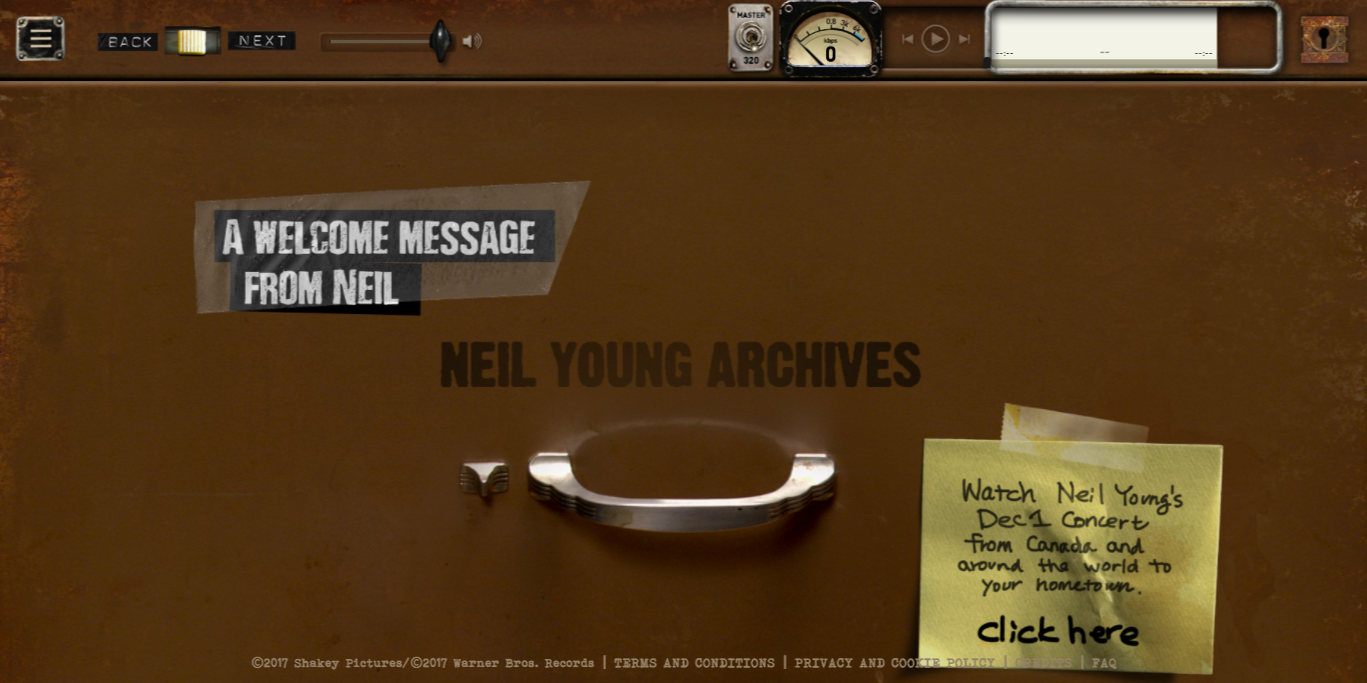

Let’s say you long ago wore out your vinyl copy of Comes A Time, Young’s lilting folk-rock outing from 1978, and visited the archives for the first time hoping to hear it. You would first find an interface that my colleague Winston Cook-Wilson aptly described as resembling a Carmen Sandiego CD-ROM game from the late ‘90s. Rather than a clean and minimal catalog of albums and songs a la iTunes or Spotify, there’s an image of what appears to be some sort of steampunk filing cabinet, complete with copious switches and meters, and for some reason, a skeleton keyhole. You click to open the drawer.

Inside is a big cartoonish file folder for every single song in the Neil Young canon, starting with the most recent. This is a man, you’ll recall, with 39 studio albums, each in the neighborhood of 10 songs long, if not more. There are hundreds of these file folders, but only about a dozen fit on the screen at any one time. There is no immediately apparent way to search them, and so you begin endlessly scrolling until you see the entries for 1975’s Zuma and figure you’ve gone too far. You scroll back and realize that Comes A Time is missing from the archive altogether. Confused you open Zuma instead, pulling up an old-timey notecard with the tracklist on it, and click the button that says “PLAY ALBUM.” The album’s second song starts playing, because the actual opener is inexplicably absent as well.

The Neil Young Archives, in other words, are not quite as comprehensive as advertised. (It’s likely that this is simple oversight, but given Young’s strange curatorial tendencies over his own catalog, the possibility of deliberate omission shouldn’t be ruled out entirely.) Aside from that quirk, there are the design problems to contend with as well. The Archives never quite shake the visual feeling of vintage children’s “edutainment.” But here’s at least a more coherent way to browse than via the file cabinet system, if you click through to the timeline view, which presents each album cover chronologically. I spent the morning dumbfounded that Neil would expend the effort to create this archive and neglect to include any sort of search function, then finally broke down and watched a charmingly amateurish 10-minute tutorial video, which Young narrates himself while tooling around the site onscreen. I learned that you have to click the skeleton keyhole to make the search bar appear (of course!), a detail so strange and counterintuitive that you can practically hear Young insisting on its inclusion, against the protests of his web designer.

From that point, digging through the Archives was a joy, even if the first album I picked out to listen–1981’s weirdly new wave-inflected Re-ac-tor–was missing a couple of tracks as well. Any excuse to revisit Young’s catalog is welcome, and each record comes complete with high-quality images of its original sleeve and liner notes for your perusal, which make the enterprise worth it even if you have a hard time hearing the sound quality difference from Spotify. (Never forget the time that he earnestly sang “Don’t want my mp3” through a haze of guitar distortion on 2012’s Psychedelic Pill.) In the coming weeks, I intend to dig deep into Young’s ‘80s and ‘90s wilderness years, albums that even a fan like me could use to spend some more time with. “Don’t forget to have a good time, and try not to get lost,” Young says happily at the end of the tutorial video. We’ll try.