For all his boyish charm, Chance the Rapper is painfully aware of violence and death. He was 18 years old when he watched his close friend, 19-year-old Rodney Kyles Jr., die after being stabbed in street fight, a trauma he recollects on “Acid Rain”: “I seen it happen, I seen it happen, I see it always/ He still be screaming, I see his demons in empty hallways”. “It could have been Chance,” his father Ken Williams-Bennett said about the tragedy. Chance learned to navigate through the darkness and survivor’s guilt in order to live–at some point that manifested as clarity, and was delivered by song.

While 2016 saw the rapper release his own acclaimed project, Chance’s performance on “Ultralight Beam” was arguably his strongest, an out-of-body realization that dreams and the fulfillment of them don’t have to be mutually exclusive. On The Life of Pablo, an unashamedly maximalist album, “Ultralight Beam” was its sparsest composition–its color and warmth rooted in the human voice instead of overwrought production. West references the Paris attacks during his doleful prayer; Kelly Price follows up by conversing with God, taking the spartan production for herself. The negative space only adds a sense of desperation to their voices.

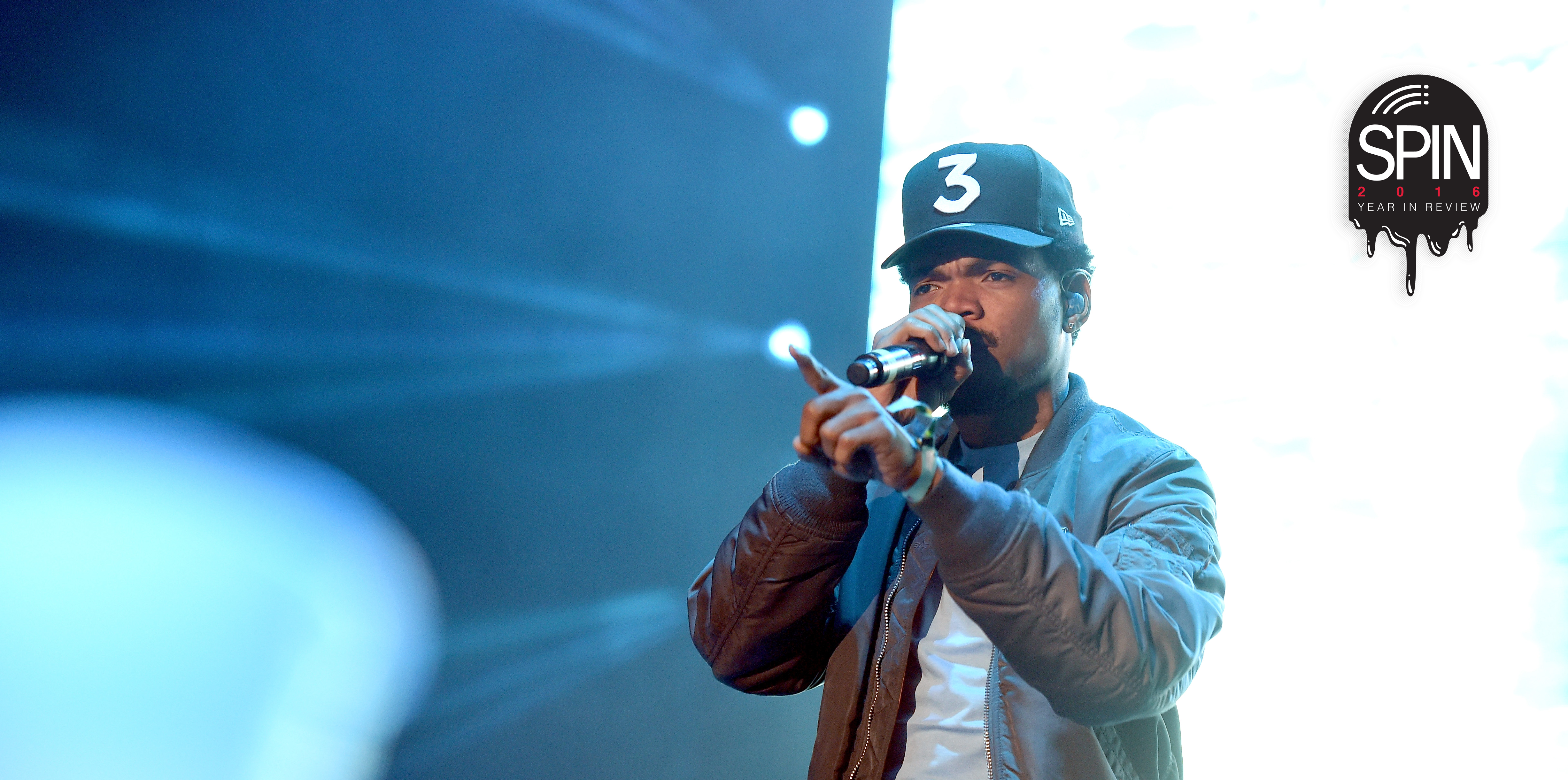

And then there’s Chance, who doesn’t only contrast his guests with his joyful bewilderment, but simultaneously assumes the role of the everyman bowing with humility. His testimony acts as a condensed autobiography. He spends the first third of his verse projecting faith—religious and in his ancestry—as a Herculean feat (“Foot on the Devil’s neck ’til it drifted Pangaea / I’m moving all my family from Chatham to Zambia”). He breaks his flow mid-verse to plainly proclaim, “This is my part nobody else speak.” We lean in and he repeats himself, this time in whisper. It translates into a call-and-response during live performance, a shared humanity. This year, “Ultralight Beam” played as Kanye West’s fortress descended at the end of his Saint Pablo shows. In contrast, the song is a centerpiece in Chance’s concerts is a centerpiece, a spotlight moment for West’s brightest pupil.

Also Read

GEAR THAT MADE THE GAME: Rap Machinery

The weight of the verse is thanks to the same manically deployed vocal techniques he first stunned us with on Acid Rap–the styling of his words is easily conversational and dizzyingly efficient. He sings “Glory be to God” with a throatiness that recalls church choir exaltations. He stretches the rhyming syllables in “Let’s do a good ass job with Chance threee / I hear you gotta sell it to snatch the Grammyyy” into an earworm, transforming a personal ambition into a democratic wish. He evokes icons (Arthur, pre-meme; Martin and Gina), elicits Pavlovian excitement with phrases readymade to be stitched onto decorative pillows (“You can feel the lyrics, the spirit coming in braille.”) There’s such a high amount of joy and reverence flowing back to the central thesis: “I’m just having fun with it / You know that a nigga was lost.”

As he shouts those lines, the horns swell for a young man casting away pain and kneeling in praise. This was a felt moment of salvation, a moment where the glimmer of light points toward the infinite. Last February, Kanye and Kirk Franklin stood aside and smiled with pride as Chance performed “Ultralight Beam” on Saturday Night Live, the masters letting the future manifest his will. For disciples of Kanye and Chance, it was like a prophecy fulfilled. Pangea was a worthy sacrifice for that scene.

https://streamable.com/e/9szx