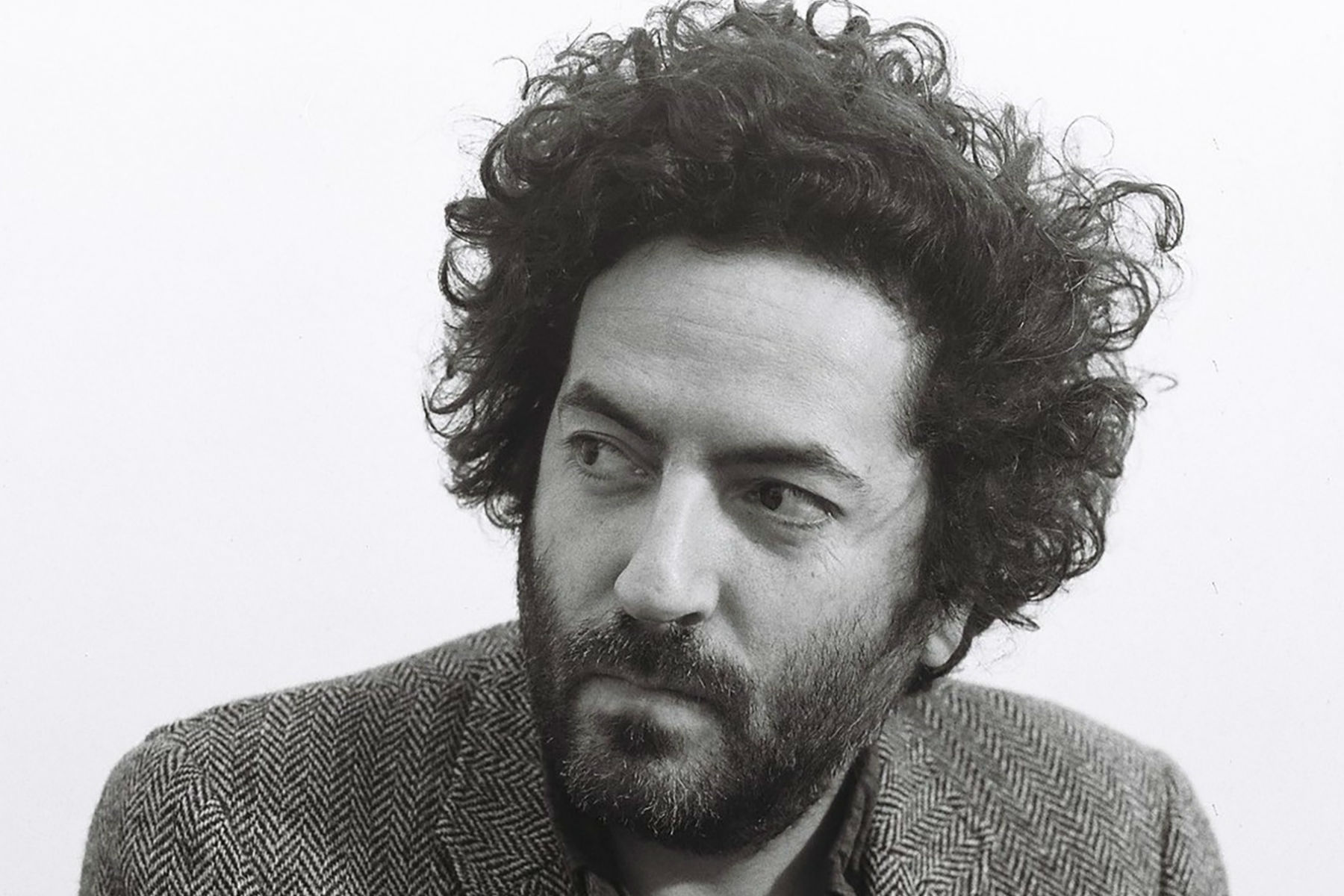

Twenty or so years ago, Dan Bejar was, as he puts it, “a f**k up” — a nondescript twentysomething, little money to his name and plenty of time on his hands. “I wasn’t, like, a mess,” the 42-year-old says. “I just didn’t give a thought to security.”

Just four years ago, Dan Bejar cemented his status as one of the most swooned-over singer-songwriters working, thanks to Kaputt, the ninth album released under his Destroyer moniker. Inspired by the sounds of ’80s U.K. radio, the 2011 LP relished in soft-rock ambiance — saxophone, synths, and keyboards aplenty, aided by Bejar’s romantic but knowingly cryptic lyrics — and proved to be a late-period coup for the Vancouver native. Suddenly, his songs were being played at strip malls, winning over longtime detractors, and earning him late-night television appearances; recently, SPIN named Kaputt one of the 300 Best Albums of the Past 30 Years. All of that success and recognition was overdue for an artist who, over the course of the late ’90s and 2000s, put out a string of restlessly creative full-lengths (highlights include 1998’s homespun City of Daughters, 2002’s glam-folk suite This Night, and 2006’s chamber-rock epic Destroyer’s Rubies), adding up to one of the richest, most inspired songbooks in modern music, indie rock or otherwise.

And early last month, Dan Bejar enjoyed a beer in Brooklyn while looking back on his career and ahead to Poison Season, the long-awaited follow-up to Kaputt. Out August 28 on Merge Records, the upcoming album trades in bluster (the horn-blown lead single, “Dream Lover,” wouldn’t feel out of place on E Street), as well as solitude (the refined string arrangements found on “Forces From Above,” “Hell,” and “Girl in a Sling”). Bejar talked with SPIN about the making of his newest record, his personal favorites in the Destroyer catalog, and why he wouldn’t give any advice to his younger self.

Poison Season is your tenth record as Destroyer. Does that feel especially momentous, or is it like every other record, just the newest project?

Honestly, I lost track of the numbers around seven or eight. I think on the one-sheet for Kaputt, it was like, “Destroyer’s ninth record.” I just kind of shook my head. It felt obscene and so old — and funny that that would be something the label would want to remind people of. In Europe, where it wasn’t until Kaputt that anyone gave a s**t about Destroyer, they actually had to pretend that sentence didn’t exist because the idea of them getting on board nine records in was too insane.

Does it make you worry to see that number? Are you concerned that people will think you’re past your sell-by date?

No, I encourage that. I like to remind people of my age and how long I’ve been doing this. It’s quite the opposite with other people, who like to gloss over it or tell me that it’s not important. But I insist on paying a lot of attention to generation gaps, different movements in culture, the fact that when I say a certain word it could have a very different meaning from when someone born in the ‘90s says that exact same word. I like the differences. I find pretending that people are all the same to be creepy and only really of value to someone who’s trying to sell something.

Was there a time period or a moment where you first recognized that you were on the other end of a generation gap?

Yeah, the first time I came to New York. I was really old — I was 28. It was 2001 and I was crashing in [Williamsburg], which has changed a lot in the last 14 years. There seemed to be two main things going on. One was a bunch of bands that dressed like they were in a gang. Fourteen years is a long time ago, so I don’t know if you know what I’m referring to —

Interpol, the Strokes.

Yeah. So that was new and that was very different from the ‘90s style of American rock bands — and the fact that they were taking tips from a certain new wave culture, which was happening a little bit on the fringes in the ‘90s, but not in such a full-on way as what the Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol, and the Rapture were doing. That was one thing where I was like, “This is happening outside of me. Even if I say, ‘This song is good, this song is bad,’ I’ll never truly be a part of this aesthetic.”

And the other thing was an urban-hippie, art-school style of music, out of which, say, a band like Animal Collective was born. And that I really liked — it spoke to me more than these CBGB-style bands, even if I couldn’t find the lyrical entry point into the ambient-folk, hippie-noise kind of stuff. I was very word-driven at that point. Those were two things that made me feel old at the age of 28.

“The idea of wanting to join some band is despicable — you should just make something.” — Dan Bejar

I’m turning 28 in the fall, so I’ll prep myself.

It’s totally fine. I think it’s the most natural thing. It’s more acute if your work is in a culture business, especially if you’re in show business, because at some point you understand that the main demographic you’re supposed to be addressing is… What is the prime demographic for music? Sixteen to 26?

I’d say that sounds about right.

So, I’m now supposed to be attracting the ears of people who have more in common with my daughter than have in common with me. I don’t know how many multiple generations of gap that is.

You started Destroyer by fooling around with a four-track recorder. Did you have any idea or hope that that would turn into a full-on career or body of work?

No, no. The idea that someone would actually pay for the manufacture of 500 CDs of the first Destroyer record — a local label in Vancouver — seemed like some bizarre lottery that I’d won. But you have to understand that the Pacific Northwest is a place where careerist aspirations are, I think to this day, considered extremely gauche.

I had friends who were in a band called Zumpano, who are probably one of the lowest-selling Sub Pop bands of all time, but they still were on kind of a stipend and they covered their rent through their many money-losing tours. And it seemed like the most fantastic thing. But to actually make a living out of it? It seemed divorced from reality, and slightly wrong. I was young — you’re talking about someone who was 22, 23 years old — and it seemed like art and commerce had no business laying down together. It’s not that I didn’t like bands that were successful — Pavement sold records, Guided By Voices sold records — but it seemed like an accident.

Plus, I started in earnest in 1995, which was the year rock’n’roll collapsed. All of the people who signed the Boredoms lost their jobs, all of the major-label dabbling in rock was over. People stopped caring about indie rock, people stopped caring about singers. If you sang, you had to either be an alt-country singer or maybe like an Elliott Smith- or Rufus Wainwright-style singer and go to L.A. and make a real expensive singer-songwriter record. But, in general, it was when electronic music really started taking over, post-rock happened. So if you did it, you really had to do it because you liked it.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”155462″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/07/destroyer-dan-bejar-poison-season-new-album-interview-145×145.jpg”]

What do you think it is about the Pacific Northwest that makes careerist ambitions so distasteful?

I’m not exactly sure. It could be the rain, it could be the fact that it’s West Coast but without any of the real glamour you would find in a boutique city like San Francisco or the messed-up, giant village that L.A. is. It’s quite isolated, compared to other places. If you’re a touring band based in the Pacific Northwest, it’s actually kind of hard.

I’ve heard that people in Seattle don’t tolerate it when someone leaves town, achieves success, then comes back and acts like they’re a big deal.

In music, if your record’s really good it will stand out — someone somewhere is going to notice it. But if you move to New York or L.A. it is your plan to get ahead via something that is not musical — like some kind of social enterprise, being in the right place. I still embrace that as being a scumbag move. I understand it for some careers, maybe; if you’re serious about theater, your options are limited unless you go to certain cities. There’s a couple of them in North America. Or, if I was a journalist living in Canada, I’d be kind of f**ked if I didn’t move to Toronto. I feel like music operates outside of those laws and there’s a history of people moving to L.A. or New York not for the purpose of making great records.

Music probably operates outside of those laws now more than ever.

Yeah, because what you’re doing is making a record that people buy, right? It’s not like a handshake in a bar. And usually it doesn’t work. The bands that move somewhere because it’s the epicenter of something, it’s usually a f**king failure. Like, Fischerspooner doesn’t work outside of New York because it doesn’t make any sense — because when you put on the record it’s not good and you don’t understand the different social cues that are supposed to alert you to the fact that it’s fake-good. And there are other bands whose names I won’t mention that actually are a less violent example of that.

If you have the idea to move to and piggyback onto a specific scene, it’s probably already dead.

It’s probably done by the time you know about it. The idea of wanting to join some band is despicable — you should just make something.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=xKpLY6bn4A0

Was it around the time of City of Daughters where you realized that this could be your path in life?

City of Daughters is when I started writing songs all day long. At that point, I didn’t think of it as some kind of career. I was just a f**k-up; I didn’t think in terms of careers because I didn’t think of more than one day at a time. But what I did know is that I was writing and playing the guitar constantly. That’s the point where I was just consumed by music and really delving into the history of music, but really the history of a certain kind of music: English music from the early ‘70s and glam rock. That’s when I put a band together and we actually rehearsed and started playing shows. That was the band that led to making these records — Thief and Streethawk — and after that I got signed to Merge.

But, yeah, City of Daughters is an important one. I went to a foreign space, which was a studio, albeit a basement studio. So, it’s not the highest of fidelity, but it’s definitely not me on my four-track. And that’s when I met John Collins, who’s been the longest collaborator that I’ve had, whether it’s been on Destroyer records or the New Pornographers records.

When you say you were a f**k-up, do you mean you were just directionless?

I was just like everyone else: broke, go to the bar, hang out with friends, stand in the basement. Standard twentysomething stuff. I wouldn’t have stood out at all — I was someone on the scene, into music and movies and books, just living on the cheap. But I was always doing s**t, because that felt good — constantly making things. And that kind of went away. That was a big shift, too, when you lose that. Because you first discover this muscle and you flex it nonstop, and you grow, and at some point things change and the process of how you make art becomes a different thing; maybe like a less exciting and definitely more isolated experience.

What was the point where that changed?

I think it’s pretty common with age that you slow down and become more thoughtful. You’re just spewing it out less, you’re not an unconscious beast. I’m trying to think of a time where I truly started to slow down, but… Probably in my early or mid-thirties. After Rubies came out, I probably started to slow down a lot.

Ironic considering that since then you’ve achieved your highest-profile success.

Yeah, Rubies was the big breakthrough. Because the early 2000s was all about me scraping by, living off of New Pornographers songwriting royalties and just doing whatever the f**k I wanted with Destroyer. That’s how records like This Night and Your Blues happened: I was just truly following my muse, as they say, and making records that were kind of crazy compared to what people expected of me. When I handed This Night in to Merge, I don’t know if there were parades in the streets of Chapel Hill on that day.

Rubies was a very natural record. There were a lot of people who liked one Destroyer record but hated another one. With Rubies, I don’t know if everyone decided that it was my best record, but everyone could agree that it was good — as far as people who actually cared about Destroyer. At that point, I realized that I could probably get by doing that band.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=EI2Q2Ls37UM

Were you surprised when people reacted so warmly to Rubies, or did it make sense because that record came so naturally to you?

It felt good making it. I maintain that the best versions of those songs are still in a side-room of my house where we practiced, off of the kitchen. When we first did it, I actually felt like it was too easy-listening, or a dad-rock vibe that would be rejected. But it was also very dense, lyrically. There’s still a lot of rambling — song-wise, it’s quite loose. But it did seem like a very natural presentation of what I did and what the band could sound like and it was probably the apex of a certain style of writing that I had been working on for the previous ten years.

I think with Rubies I embraced fairly traditional songwriters — Bob Dylan, Van Morrison — and those image-heavy rants, but with a melodious, loping, folk-rock background. But any kind of success is totally surprising. The words were still a hurdle.

Is Rubies your favorite record of yours?

No. I like it. I like This Night a lot — it’s closest to the kind of rock music I like to listen to and it was the beginning of me letting go of this obsession with song structure and popcraft. I like City of Daughters a lot — not that I listen to it, it sounds weird to me, but it seems like a very true document of where I was at that time in my life. It’s really the only true bohemian Destroyer record. I think Streethawk is a pretty strong collection of songs.

How do you feel about 2008’s Trouble In Dreams? That record is undersold and sort of forgotten because it came out in between these career peaks. Do you feel like it got a raw deal?

I’m part of the reason why maybe it got a raw deal. I’ve been going back to that record and thinking about it. I haven’t listened to it, but there are songs on it that, more and more, I’m tempted to try and tackle onstage. It’s probably got my favorite lyric sheet of any Destroyer album. But singing-wise and musically, there’s something not-nailed about it. Probably because it did exist in this interim time where I was writing very dense, imagistic songs. I was already leaning towards a Kaputt-style of singing that was softer and more thoughtful — less drunken and edgy.

I didn’t know how to sing the songs on Trouble In Dreams, the vocals did not come easily to me. And that disconnect between the writing that you love and are really proud of, but the fact that the song still doesn’t work, that was really informative for me. It was kind of the death knell of a version of myself as a writer [and the start of me] becoming more of a singer.

I feel like I was just really nailing it, line after line. My batting average as a writer was very high. I was living in Spain at the time that I wrote those songs, reading a lot of Spanish surrealists, really embracing surrealism for the first time ever.

“Playing in a Kaputt cover band did not feel good to me.” — Dan Bejar

Is there a favorite line you have or is at all just one big piece to you?

Well, when I wrote the song “Shooting Rockets,” I thought it was my masterwork. So the fact that it’s not affected me, I’m sure. But I felt like it was a heavy piece of writing and I was writing outside of myself, maybe above myself. And maybe that’s one of the reasons I had a hard time singing it — I was punching above my weight.

If Rubies was the breakthrough, how do you categorize Kaputt?

Well, Rubies was a breakthrough but on a real indie-rock level. Kaputt was the first time that I ever got exposed to this 2000s-style world where indie rock just collapsed into commerce. You try and play television, you try and play giant festivals, you try and get your songs into ads, like syncs — sync-rock. And I started to rub shoulders with that world. Not in a way that’s very exotic; in a way that’s super commonplace and everyday for most bands. But to me it seemed strange.

Stranger than people who never heard Destroyer liking Kaputt was the fact that people who had actively hated Destroyer for ten or 15 years liked Kaputt. The coming-out-of-nothing thing was weird, but not super-weird. The total-turnaround was pretty strange. And the main thing that happened was also, for the first time ever, we found an audience in Europe, so we started spending a lot of time over there. I wasn’t totally shocked because the aesthetic of the record was very Euro-centric.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”155464″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/07/destroyer-dan-bejar-poison-season-cover-art-145×145.jpg”]

Why do you think Kaputt was the larger breakthrough compared to Rubies, which was an album that many people liked?

There’s three answers that I can think of. The first is that judging from the amount of questions about chillwave I had to answer in 2011 and 2012, that [Kaputt] lined up with some kind of zeitgeist that was happening amongst a certain group of bands that were ten, 15 years younger than me. That was an accident — I wasn’t listening to a lot of new stuff. I knew about Ariel Pink, but that was about it.

The second is that I cut the word count. There’s maybe one third of the amount of words that were in Trouble In Dreams — that’s a lot. And they’re sung quietly and flatly in a way that didn’t really interfere with the music. It was part of the music and that’s a pop-music trick. That has to be present in pop music, unless you’re some kind of diva and I don’t think my voice came across as some Celine Dion-style voice. My absence from the record helped.

The third thing is it’s a very coherent record, it’s very cohesive from beginning to end. The tone, the palette is very much one thing, which is very important in pop music and I wanted that going in, but I was surprised at how much we nailed it. I knew we were making a studio record — a studio construction — in a way that we had never really done before, aside from Your Blues, which is an experimental record. And it was based on a lot of sounds that were used in music that you would hear on the radio, in the U.K., in the early to mid-1980s. To me, those sounds were definitely part of my upbringing, my musical formation. I didn’t guess that that would become part of some kind of vogue for the first half of the 2010s, but it did, so that helped the record out.

Those are all slightly cynical answers. Maybe there’s something at work in Kaputt… The songs are born of these kind of sweet lullabies that I mumbled to myself, into my phone. So there’s a kind of lost, nostalgic quality — fragments just floating by. But I did want the record to be played as public music in a public space, to work in that sense, and that’s something you cannot say for any other Destroyer record — where my singing was designed so that someone would go and ask for the person behind the bar to turn the record up. Before, the vocals were always something you had to reckon with and grapple with, it couldn’t just exist in the background. And that’s not the case anymore.

I remember that maybe a month after Kaputt came out, I heard “Savage Night at the Opera” in a Banana Republic and it just felt crazy — even after a decade of indie rock songs being popular and used in advertising. I was like, “Is Banana Republic cool all of a sudden?”

No, it’s that Destroyer’s not cool all of a sudden. I remember those days, when it was like, “Man, I heard your song at such and such.” And I’d be like, “Yeah, Banana Republic’s the new nightclub. That’s where music goes down.”

People who had a history with Destroyer — they’re a small contingent, they’re not very vocal — but there’s a certain group of people, I think, who find Kaputt to be a questionable move; people who were attached to a style of writing I once did, who mourn its loss; who found a certain fury in the singing before — albeit a woozy fury — [and] maybe miss it.

But I can only make the kind of music that pleases me — that’s where I’m at. I don’t think I made a pop record with Poison Season, I don’t think it pushes the same buttons that Kaputt did. I don’t expect it to appeal to the same people. I don’t expect it to function in Banana Republic the same way that “Savage Night at the Opera” did. I am not troubled by any of those things.

If it did really weird you out when people who hated Destroyer started saying they liked Kaputt, I could understand if that would make you almost resentful of that record.

I’m not resentful. I think it’s good at what it does and I understand its appeal. When we toured the record, when it first came out, it took so much work just to figure out how to play those songs, because they were all pieced together on a computer — and playing in a Kaputt cover band did not feel good to me. That’s why I more embrace the 2012 version of Destroyer, which is the version you hear on Poison Season.

I like the music [on Kaputt], and I’m lucky that it was embraced. It f**king gave me the kind of advance that I needed so I could blow it all on making a record that sounds like Poison Season and not one that’s recorded as a piece of computer trickery. I became comfortable for the first time as a singer on stage touring that album. Lots of good things came of it.

From what I’ve read about the new album, I expected Poison Season to feel a lot more difficult, like a traditional turning-your-back kind of record. But it’s not quite that.

No, most of the band is the people who played on Kaputt. I always go into every record thinking that it’s going to be severe and alienating and somehow reflecting the darker end of the lyrics. Every record’s been like that, where it ends up way more melodious and accessible than what my initial idea was — and that’s because I’m a conflicted soul that way, and I always will be. [Part of me thinks] that something has to be an absolute, individual, isolated statement and the other part of me is someone who wrestles with pop culture and loves melody and the naturalness of phrasing in songs and traditional song structure. That divide will always be there, but the more I become a singer and the less I think of myself as a writer, I keep going towards whatever the song needs.

Are you happy with your voice on the album?

That’s one of the things I’m most happy about. It’s rare for me to say, but for the most part, I feel like I really sound like myself. I like that.

You’ve talked about the influence that religion had on this record, and religious imagery is all over a few of the songs. Is that subject always attractive to you, or do you think there’s a specific reason why you’re thinking about that stuff lately?

That’s a good question. I will say — and “attractive” is the right word — it’s always attractive to me. I don’t know if it’s something that necessarily drives me as a person, but when I see it in art, I love it almost across the board. I feel like it’s a huge part of the songwriting traditions that I love. When you’re singing a song, it has to be life or death. There has to be something at stake, and these concerns are part of that.

It’s not like I expect to find any answers, but I like the idea of striving for some kind of light or revelation. And I like the idea that the striving is futile, that the answer’s not the thing, but the struggle is the thing. And that’s what gets documented when we open our mouths or write stuff down.

As far as anything I might be going through… I think it’s very natural to get older and start to get consumed by these things. You reach a certain age and you feel death’s talon resting on your shoulder — your mind is gonna go there. It’s gonna go there more and more. And also, lyrically, all of the poetry lies in those things. Language becomes rich the minute you start addressing those concerns.

To me, the record sounds like a lost soul. It’s not an abrasive listen, but I feel like it is a darker listen than most Destroyer records. There’s a [sense of] foreboding, like a figure that feels ill at ease in the world. Maybe that’s something I passed through — I don’t necessarily think of myself in those terms, but there’s definitely a distance from the world. Maybe that just creates a way of seeing the world as a hostile place.

Is there any piece of advice that you would give your younger self if you could?

No, no. I’m famous for not being able to give advice to anyone. No one comes to me for wisdom, because I believe 100 percent in their problem. So if someone comes to me in trouble, all I can think of is that they’re completely valid in being worried — that they’re right, they’re totally f**ked. I would corroborate younger Dan’s worst fears in a way that I would just shut myself down.