If you’ve got to go to prison, you could do a lot worse than the Idaho Correctional Institution in Orofino. The 574-inmate facility is tucked into a picturesque valley on the state’s rugged northern panhandle, along the trail once blazed by Lewis and Clark. The thin window slits in many of the general-population cells on the prison’s newest section — called “A Block” — offer views of the surrounding green-brown foothills and pine forests, as well as the crisp rushing waters of the Clearwater River, a world-renowned fly-fishing spot. Despite its northerly latitude and the snow-capped mountains not too far in the distance, the weather here remains reasonably mild year-round. Minimum-security offenders have opportunities to get outside the 15-foot razor-wire-topped chain-link fences that surround the prison’s perimeter by working on inmate firefighting crews and doing roadwork and construction jobs nearby. It’s also one of a growing number of American correctional facilities where prisoners have access to a digital library of millions of songs. But make no mistake: This is not some country club for exiled Wall Street barons.

“We are a multi-custody, all-male facility,” Terema Carlin, the prison’s warden, tells me when I visit on a Wednesday in mid-April. “We have people who are paroling out tomorrow and we have lifers here.” There are protective custody units for inmates — often sex offenders or former cops and corrections officers — who’d be in danger if they mixed with the general population, and segregation units for those prisoners prone to violent outbursts. “We don’t have too many offenders who are management issues,” she says, “but we do have a few.”

Carlin does not fit the popular image of a prison warden. She’s in her late 30s, and is slim, sharp-witted, and personable. She and her deputy warden, a friendly, easygoing guy named Aaron Krieger, both began working at Orofino as corrections officers in the late ’90s and have never left. Their approach to corrections puts the emphasis on rehabilitation, or “habilitation,” as Carlin puts it as she leads me through the facility’s front gates, because “most of the guys in here never got taught the skills for how to cope with the real world.”

We pass though a few buzzing doors and soon are standing in a control room looking down on the protective custody unit, where offenders, most dressed in white T-shirts and loose orange pants, are milling around the common area outside their cells. The space is roughly the shape of a large trapezoid, with some simple exercise equipment in the center, several round metal tables, and a medium-sized flat-screen TV up against one wall. A few of the inmates are sitting at the tables talking, two look to be doing laps of the area, and another is sitting in front of the TV, hands on his knees staring at the screen. Among the two-dozen or so inmates, one stands out a little: He’s of average height, average build, with his blond hair cropped closely to his skull, and it’s not even the big headphones clamped over his ears that set him apart. It’s the lightness. As he walks around the unit, he’s bobbing his head, staring down at his MP3 player, scrolling through songs. If you could block out the background, you might think he was strolling around a college campus or a public park, almost floating. Carlin sees me looking at him.

“They can listen to their music players pretty much anytime they’re in the unit,” she says. Idaho began allowing inmates to have specially designed prison-issue MP3 players three years ago and somewhere between 15 to 30 percent of offenders in Orofino have bought them through their commissary accounts. “MP3 players are a lot like televisions. They’re a really good babysitter. It keeps their minds from running and maybe creating some chaos.”

Whether it was the seminal recordings Leadbelly made while incarcerated in Louisiana or Johnny Cash touring California prisons or just the countless inmates who have passed time huddled in their cells listening to a Walkman, music has long played an active role in inmate life. There’s always been a struggle to balance the practical needs of a corrections environment with the benefits that music can provide for prisoners; but just as the digital revolution has upended the way we listen to music in the outside world, it is beginning to fundamentally change life inside prison walls too.

“They love their music players so much,” says Carlin. “The people that have them want to take them wherever they go.”

For decades, most corrections departments allowed inmates to purchase CDs or cassettes through approved outside vendors — sometimes the same vendors who sold them toothpaste, shampoo, and hairbrushes. But now, at least a dozen states and some federal prisons offer inmates the opportunity to buy special prison-issue MP3 players and download music through systems, informally called “Music Wardens,” designed specifically for prison use. According to Brian Wittrup, operations manager for the Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections in Ohio, it took awhile to make the change from CDs to MP3s, mostly due to institutional technophobia.

“In general, a good rule of thumb is that prisons are usually about ten years behind regular society when it comes to technology,” he says. But once Ohio made the switch five years ago, the advantages of digital music quickly became clear.

“First of all: Control,” he says. “Music that promotes violence or gang activity or is inflammatory or derogatory toward particular races is banned inside of our prisons. With MP3 players, you have the ability to select the songs that inmates can download, so it gives us the ability to control the songs that they have. We base it on Parental Advisory warnings, but we actually have a committee that evaluates all types of media. Secondly, CDs and cassettes [Yes, some facilities still use cassettes — see this story] have to be mailed in from external vendors, and that was a very big avenue for the importation of illegal drugs and things like that. So this eliminates the possible introduction of contraband. The other big benefit is that space is limited inside of prisons, so normally an inmate could only be allowed maybe 10, 15, 20 CDs or cassettes. Now they can have players that are 8 gigs. That’s a lot of songs.”

The players are also electronically imprinted with the name of the inmate who bought it, and most of these systems have several additional layers of theft protection built into them.

“Thievery leads to violence,” says Wittrup. “But if one of these MP3 players is stolen, we can remotely deactivate it. So it takes away the motivation to steal.”

There are other advantages too. CDs often could be fashioned into crude weapons, and inmates frequently repurposed the motors from cassette players to make tattoo guns. But these MP3 players have no moving parts, and even if an inmate could break them into pieces, he wouldn’t have much of a shiv.

In Idaho, prior to the introduction of the MP3 program, the only way for inmates to listen to music was on an AM/FM radio. As Krieger, the deputy warden, points out, in a rural locale like Orofino, that can be a problem.

“There’s not a whole lot of radio stations here,” he says. “If a person likes rap, they’re not going to have access to that at our facility. So this keeps them connected. Things change while they’re in here, but they keep the music updated and the offenders are able to keep up on that stuff. And actually if you think about transitioning them back into the community, the more they can keep up on things, the easier it’s going to be.”

Carlin and Krieger take me to the prison’s cafeteria while a group of inmates are eating lunch to show me the music warden. It’s a rather unassuming-looking black box with a computer screen on the top. This is where inmates plug in their MP3 players to load new songs, and a few do just before sitting down to eat what appears to be chicken and rice.

Idaho’s digital music system is the handiwork of Access Corrections, which is part of a company that has been selling personal items and administering prison commissary accounts since the mid-’70s. They expanded their offerings to include music in 2009, but the system has not been without glitches. Krieger tells me that because the link from the music warden to the Access database is via satellite, songs don’t always download very quickly and there are sometimes blackouts. While I’m standing next to the box talking about it, one inmate assumes I work for Access, and asks me when we’re going to update the songs on there. While the catalog has more than five million tracks in it, it only gets updated once every few months.

After lunch, I sit with Britton Weaver, a thin, clean-cut guy in his twenties who is serving “two plus eight” — that’s two years before he’s eligible for parole, plus up to an additional eight years, depending on the vagaries of the parole board, amongst other things. He robbed the hotel where he once worked. He shows me his MP3 player — it’s small, about the size of an old-school pager, with a clear plastic shell and runs on AA batteries. Access sells two models, Weaver tells me: a 4G for $127 and an 8G for $153. This is the second player he’s had. The first broke, and since the warranty had run out, he had to buy a new one.

“Compared to an iPod, I would consider this like a clunky Walmart brand MP3 player,” he says. “Like a $50, run-of-the-mill plastic one for kids. But in here, it’s either this or a radio, so it’s well worth it.”

Weaver shows me how he orders songs. Access’ whole catalog of tracks is viewable on the player’s screen and with a few clicks he orders Cassie’s “King of Hearts” for $1.70, which is automatically deducted from his commissary account. Now he just needs to plug it into the music warden, so the song can be downloaded to his player.

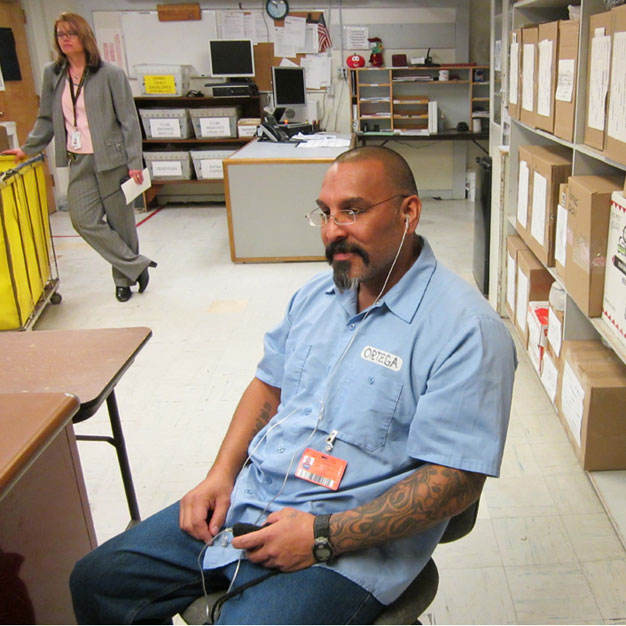

The price of both the player and the songs sets a pretty high barrier of entry for inmates here, many of whom do not have family on the outside who can afford to stock their commissary account with the kind of money to make an MP3 player a worthwhile purchase. Inmates earn money by working jobs in the prison, too, but the going rate is between 10 and 30 cents an hour, which means it’ll usually take a full day’s work to earn enough for a single three-minute Cassie song. As Richard Ortega, a bulky Texan who has six more years left on a sentence for his fourth drunk driving arrest, put it to me, “You can save money to buy songs, but then you’ve got to think about, ‘How am I going to buy soap and deodorant and all that?'”

Ortega also complained that trying to get in touch with Access to report problems is inefficient and time-consuming. Another prisoner, Mike Cheser, a short, heavily tattooed 34-year-old who bears a passing resemblance to Social Distortion frontman Mike Ness, says that when his player broke, he had to scrounge together $10 to pay the shipping charges to send it to Access, then it was three months before he got it back.

“During those three months, I’m sure I became a little bit more antisocial,” says Cheser, who is currently locked up for violating his parole from an earlier arrest on drug charges, but is eligible for release in four months. “You get tired of people in prison. I like to be able to block out some things. It’s an easy way to escape to a better place.”

Cheser even sees the benefit of not having access to the objectionable songs or lyrics that are screened out by the Idaho corrections officials. He says he’s “done a lot of time,” but at Orofino he’s been taking anger management and drug and alcohol rehabilitation classes for the first time.

“If I’m listening to [Bay Area MC] Andre Nickatina’s ‘Cocaine Raps’ or ‘Fly Low Like a Blind Bird,’ where he’s talking about drinking beer, smoking cocaine, and acting like an idiot around a bunch of prostitutes, that’s going to drive me right back to my neighborhood in my mind,” he says. “If I’m doing that, it’s more likely I’m going to relapse. It would drive past behaviors which are what landed me in these facilities in the first place.”