M.I.A. recently tweeted, “THE HEART OF ART IS MAKE IT THE ART OF ART IS SHARE IT,” but it meant more to her than an all-caps shout-out to the generous high tenet of DIY. During an artist’s lecture yesterday at Museum of Modern Art’s Queens outpost at P.S.1, she made clear that in addition to global bass, staccato double-dutch lyrics, and wartime stencil paintings, one of her favorite tools is the art of dissemination. More specifically, mastering the Internet as art project. It’s a medium that’s influenced her more than most fans know, even including /\/\/\Y/\‘s YouTube-streamer clusterfuck of a cover image and the information-freedom exegesis Vicki Leakx. “We built a community,” she said of her fans and other web-detected peoples, “that sort of felt like it was the future.”

M.I.A.’s talk, a lucid, off-the-cuff, plenty funny monologue that lasted a good hour and a half even in the pre-winter chill, was a history of her own artwork pegged to her new book, M.I.A. (Rizzoli), in which she detailed the thinking and process behind her visual art through the years. But it was also a narrative and visual history of the Internet, with Mathangi “Maya” Arulpragasam as reflective a surface as she’s always been, emphasizing the importance of MySpace, her problem with Facebook (it looks boring) and disdain for the sameyness of current website design — and eventually finding Internet spirituality via her forthcoming album, Matangi.

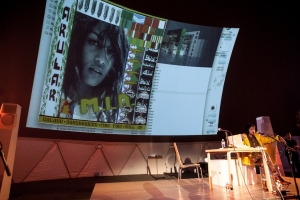

The talk started with a computer desktop. Held within PS1’s planetarium-like “Performance Dome,” M.I.A. blasted out the contents of three separate laptops on a giant projector screen, each of which contained elements from the making of her last three albums, explaining how the process of making her music started from images, screenshots, and Photoshop experiments she cobbled together over the years. Before she even considered making music, she said, her work at London’s prestigious Central St. Martins included “pre-Internet” looped footage of herself dancing in her friend Steven’s garage, crafting a style of .gif before .gifs were all that easy to craft. Just as /\/\/\Y/\‘s .gifs (by Mexican artist Jaime Martinez) predicted Tumblr aesthetic, she was making proto-viral videos before YouTube invented them, somehow precogging the web to come. She also stenciled Tamil tiger-emblazoned lighters igniting sticks of dynamite, got excited over spraypaint cans she found in oddly shaded greens. But after revisiting Sri Lanka for a documentary and transforming that to a successful art show — and a stint on a “deserted island” where she, the sole teetotaller, helped her friends come off heroin — she withdrew from art and began discovering music as her politics crystallized. “I started getting frustrated,” she said, slouching a bit in her butter yellow shearling winter coat. “Because I had a lot to say, but I didn’t have the platform.”

The rest, of course, is on the books (and in the book). Arular was a breakout hit thanks in part to the stenciled-revolutionary aesthetic she brought to it (and, apparently, fought her label over keeping intact — someone should introduce her to Death Grips). With her next album, she could afford a laptop and transformed her project into a realtime web experience. The cover of Kala was based on a PhotoBooth selfie she snapped on her Mac and IMed to someone while traveling through Africa, India, and Jamaica. She wanted to “go around the world and look at the ugliness,” she said. “You weren’t gonna fix it, but I sort of believed you could through art.” The song “20 Dollers” [sic] began as a photo she took of a Madonna-stickered car in Liberia, then scrawled across in Photoshop, a singular example of the interconnectivity between her visual art, her music, and her sensitivity towards global inequity. It was about “hood shit in a world setting,” she said, and also about “liking the aesthetics of screenshots, how the Internet can be manipulated by being super-techy.” (One thing she didn’t own up to being connected to, however: collaborators and artists who have worked with her throughout the years.)

As if to prove it, the whole audience got to spy on her desktop on a giant projector screen — a surprisingly intimate experience for an artist of her renown, in this era — including folders labeled “Versace Prints,” “Bootleg Versace,” and “Versace Outlines,” and later she confirmed that she is currently collaborating with the storied label (which would explain her many recent public appearances wearing impossible-to-procure vintage Versace prints). For her part, she had on a gold, D&G-lookin-ass, baroque-print Chelsea boot; a floral trouser; and a navy pajama top with a Peter Pan collar.

It was good style but totally overshadowed by her best mash-up ever: adorable son Ikhyd, who by the end ran up onstage to his mother, nearly four years old with doe eyes in a baby triple fat goose. He seemed happy and friendly, aiming a laser pointer and giggling with anyone who made eye contact, and Arulpragasam explained that his name was an amalgam of “a name from Israel and one from Palestine, hoping that he’ll see the conflict resolved in his lifetime.”

How can you be mad at that? She’s not a freedom fighter, but she’s opened the culture up to so much. M.I.A.’s impact on Internet music is undeniable — her emergence in 2003 with an artpunk renegade’s approach to vocals and total dismissal of stylistic barriers neatly coincided with the internet’s explosion of genre lines. Piracy Funds Terrorism! Her impact on the culture of music, too: her vehement, sometimes vague political statements were often met with equally antagonistic journalism, and her presence forced a new generation of critics to reckon with how commercial art interacts with radical politics. But if there’s a “heart of art” where the two intersect in the Sri Lankan/Briton’s oeuvre, it rests among the thoughtful aesthetic of her visual work. Her book as a collection reveals heft in a vision that, while not always clear, is undeniably passionate. “The music thing accelerated me being able to take the art out of the gallery,” she said, “and put it in the mainstream.” Here we are, 2012, better for it.