The aromas of must and dust were what stuck with you when you exited Bleecker Bob’s Golden Oldies Record Shop, the dumpy yet iconic LP store in New York City’s mercurial post-boho Greenwich Village. The scents wafted out the door, where they lingered in that no-man’s-land between Ben’s Pizza and Village Psychic. The collected fetor of decades-old cardboard, vinyl, and plastic all comingling, the whiff of oldies begging to be rediscovered.

It was unforgettable.

For the past 32 years, Bleecker Bob’s shared its air at 118 West Third Street, and it amassed a downtown New York legacy that dated back to the early ’70s. The store hosted any number of notable events — it’s where Patti Smith met Lenny Kaye, where Joey Ramone directed New York magazine readers in their 1994 “Where to Find It” issue, where Newman on Seinfeld insulted its (fictional) surly store owner, and on and on. As of Sunday, April 14, though, it was merely another façade awaiting its transformation into yet another place to buy frozen yogurt in Manhattan.

As with the 2006 shuttering of CBGB, which stood about 10 minutes’ walking distance from Bob’s, as well as any number of the City’s downtown music hubs that have closed in the last decade (the Bottom Line, Tonic, Sin-é), Bleecker Bob’s is now another signpost for the ever-homogenizing Greenwich Village. What was once the booming beatnik stomping ground that served as home to Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix, and then about a decade later, the Ramones and Blondie, now offers more and more of the amenities available at most Midwestern malls. To residents and tourists alike, the closing of Bleecker Bob’s is another high-points blow in the assassination attempt on the neighborhood’s character.

Early in my reporting for this story, the friendly, bearded man who ran the poster section in the back of the shop and who went merely by “Bill,” uttered six words that resonated deeply with me during the month and a half that I spent at the store: “This is a landlord’s town now.” It’s a sentiment echoed by the neighboring businesses and customers of Bleecker Bob’s. A few days before the shop closed, I phoned Lewis Rosenthal, the property’s landlord (according to New York City records), but despite the power he holds in the situation, he declined to comment for the story. Nevertheless, the cast of characters willing to talk, including the store’s employees, its neighbors, customers and competitors, as well as Bob himself, took the time to share their memories — good and bad — of the New York institution as it played out its final days.

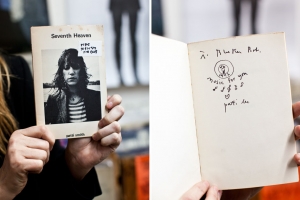

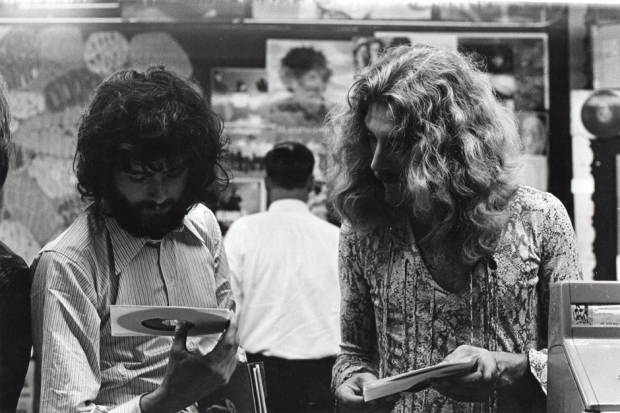

See the history of Bleecker Bob’s in photos, featuring Robert Plant, Debbie Harry, and more.

Fodor’s New York City 2012 described Bleecker Bob’s as “pleasingly messy.” Lonely Planet touted its “creaky wooden floors…and a few bongs.” Frommer’s New York City for Kids described it as “a scene out of the movie High Fidelity” that would appeal to “older kids who are into esoterica and nostalgia.” But no matter how diplomatically you put it, Bleecker Bob’s exuded the sort of gritty, romantic New York mystique that now seems to exist, for better or worse, only in ’70s Woody Allen and Martin Scorsese flicks.

The roots of the store date to September 1967, when a lawyer named Robert Plotnik (born in Baltimore in 1942) who was working for the New York district attorney, teamed up with a record-collector friend named Al Trommers, who went by the moniker “Broadway Al,” to open a shop called Village Oldies at 149 Bleecker Street. The pair had connected over their love of doo-wop and vocal-harmony groups, respectively. “I said, ‘Bob, we’ve got to get a nickname for you,'” Trommers recalls in the 2012 documentary, For the Records. “‘Robert Plotnik’ does not sound like a hip name for a hip record store. I said, ‘I’ve got a good idea. Since we’re on Bleecker Street, why don’t we call you ‘Bleecker Bob?’ And it stuck.” The duo moved locations twice before Trommers tired of what he describes as Plotnik’s increasingly difficult disposition and decided not to sign another lease in the mid-’70s, making way for the opening of Bleecker Bob’s proper and its move in 1981 to West Third Street.

Since then, the shop has resided in the same location as what was once a narrowly designed music venue called the Night Owl Cafe. In the mid-’60s, acts like the Lovin’ Spoonful, James Taylor, and Tim Buckley used its stage (where the CD racks used to live) to win over freewheelin’ folk fans, seated in and around church pews. Some of the store’s older employees guess that the shop’s dirty, rough-hewn wooden floors date back to the Night Owl days.

To take advantage of the area’s after-hours foot traffic, Bleecker Bob’s would keep a club’s hours — staying open until 1 a.m. every night except Friday and Saturday, when they were open until 3 a.m. In recent years, its painted-brown wooden record racks looked their age, with title cards representing various, painstakingly precise genres (“international punk” resides within feet of both “country vixens” and “black comedians”). The artists were alphabetized by first name. Posters bearing classic poses from David Bowie, PJ Harvey, and even Limp Bizkit clung to its walls, and atop the back’s black-and-white checkered floors, milk crates of smaller posters spanned rock history. Fans could buy four different Johnny Thunders posters that the sometime New York Doll had delivered to the store himself.

The rest of the wall space was crowded with 7-inches, ranging from the Beatles to Anti-Flag, and hard-to-find LPs, including an unpeeled copy of The Velvet Underground & Nico (Bob’s all-time bestseller in its various reissues) and expensive copies of Celtic Frost’s Into the Pandemonium and Prince’s Purple Rain. It was a dizzying display of memorabilia, heightened by neon signs, an uncountable number of clocks, and whatever the employees had blaring over the store P.A., and it culminated when you were rung up on a Cretaceous-era cash register that they kept “because we like it that way,” according to an employee.

Over the years, Plotnik acquired a reputation for a temperamental attitude, and many of the people interviewed for this feature — including three out of four employees — claimed they were banned from the store over petty disagreements, though the excommunications never seemed to stick. Still, Plotnik attracted customers willing to endure his tough-guy exterior. And because he was open-minded enough to embrace emerging musical trends, rather than focusing solely on oldies, the store found itself at the forefront of the punk-rock explosion.

In April 1977, when music critic Robert Christgau got wind of a furious U.K. band called the Clash, who hadn’t yet officially released an album in the U.S., he went to Bleecker Bob’s to buy the group’s self-titled debut as an import. He would go on to deem it “the greatest rock’n’roll album ever” and to alert readers of The Village Voice that the album was available at Bob’s. In part because it was available at the store, the album would later become the best-selling import to date in the U.S., at least according to author Randal Doane’s Clash biography, Stealing All Transmissions.

“Bleecker Bob’s record store was the first store I ever saw that was the model for the little indie record shops that are now everywhere,” says Blondie guitarist Chris Stein. “It was very funky, and Bob was a very specific odd character. There’s definitely a movie in there somewhere.”

One punk-era character — Patti Smith Group guitarist Lenny Kaye — frequented the shop so much that Plotnik offered him a job. Kaye worked at Village Oldies from 1970 to about 1975. Long before he and Smith even considered playing music with one another, Smith would come in and hang out at the store, just spinning records. “We mostly listened to group-harmony records of the South Jersey, Philadelphia area,” the guitarist now says. “We’d play Maureen Gray’s ‘Today’s the Day,’ the Dovells’ ‘Bristol Stomp,’ the Blue Notes’ ‘My Hero.’ And the occasional Smoky Robinson, of course. She’d come in and if nobody was in the store, we’d do a little dancing around. It was nice. She lived around the corner. It was our local hang.”

Kaye credits the way he played his favorite 45s from the ’60s at the store as one of his inspirations for his celebrated 1972 compilation of psych- and garage-rock, Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From the First Psychedelic Era, 1965–1968. “Late on a Saturday night, when no one was around and I’d have a beer, I’d just be pulling records off the shelf,” he says. “So when I had the chance to do Nuggets for Elektra, I had kind of a basic map of the types of groups and songs that would fit into this concept. They were my favorite records from the ’60s. I’d pull out 13th Floor Elevators, then I’d pull out ‘Liar Liar’ by the Castaways and follow that up with [Count Five’s] ‘Psychotic Reaction.'”

It was at Village Oldies where Smith made a life-changing offer to Kaye. “She came up to the counter,” the guitarist remembers, “and said, ‘Listen, I’m doing a poetry reading at St. Mark’s Church in a few weeks. I hear you play a little guitar, and I’d like to shake it up, so why don’t you come and accompany me on a couple poems?’ And from that little acorn, a beautiful towering oak was born.” Later, the pair would sell the first Patti Smith single, “Hey Joe (Version),” which they pressed on their own MER label in 1974, at the store.

In the ’70s and ’80s, Plotnik formed friendships with a number of famous musicians who would come into Bleecker Bob’s. Whenever Frank Zappa was in town, he would come by and hang out, as would Robert Plant and Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin. David Bowie would often stop in, and Plotnik would tease him by playing the singer’s absurdly Chipmunks-like 1967 single, “The Laughing Gnome.” When Madonna was a member of the Breakfast Club in the early 1980s, she would promote the pop group by calling up Plotnik. The Beastie Boys affectionately recalled a time they “stopped off at Bleecker Bob’s, got thrown out” in their 2005 single, “An Open Letter to NYC.” And Dean Wareham — of Galaxie 500, Luna, and Dean and Britta — once tried to get a job there.

“I used to frequent Bleecker Bob’s as a high school student around 1979-81, when the store was located on MacDougal, just below 8th Street,” says Wareham. “It was the place to find the newest imports, singles by the Clash or Siouxsie & the Banshees or the Cramps. I did ask Bleecker Bob himself if he might consider giving me a job, but I failed the one interview question.” That question — “Who recorded ‘In the Still of the Night?'” — was one that Plotnik would ask more than one prospective employee. (The correct answer: doo-wop harmonizers the Five Satins.)

By the mid-’80s, business was good enough that Plotnik could open a Bleecker Bob’s on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. Metal was becoming a more popular genre, and one of the store’s long-time clerks, John DeSalvo, recalls bands ranging from Metallica to Megadeth coming in to see what new music was happening. DeSalvo, who started working at Bleecker Bob’s in 1977, shortly before his new-wavey punk band, Tuff Darts, released its well-regarded debut, had several infamous run-ins with some of Bleecker Bob’s rock-star clientele. He asked Prince, “What can I do for you, shorty?” and he gave Bowie his Neu! LPs only to see the singer form the detested Tin Machine. But one of his favorite, more positive interactions was with New York City thrashers Anthrax.

“When their ‘I Am the Law’ EP came out, I bought one,” DeSalvo recalls. “And one of my customers really wanted it and I sold him mine. Of course, that was it. They were sold out after that. I told the band and said if you ever find one, I’ll buy it from you. They said, ‘We didn’t really get copies.’ One of the guys came in the next week, though, and it was signed by everyone [in the band]. It was sweet of them.” Anthrax drummer Charlie Benante was the one who came by the shop. “John was so cool,” says Benante. “He would hold stuff for me. If I was on tour, I would call and say, ‘Could you possibly hold this for me and I’ll come in when I’m back?’ And he’s like, ‘Yeah, no problem.'”

Benante says he would frequent the store so much that it was like his second home. “The best thing about Bleecker Bob’s is at 1 or 2 in the morning, you could go in there and hang for a while and go through the bins,” he says. “And right behind the counter is where [Bob] would display all the new shit that would come over from Europe or England. I remember days, after being out drinking, going to get pizza and then walking into Bleecker Bob’s and getting the new issue of Kerrang. I still have a huge Beatles, Sgt. Pepper poster that’s hanging up in our studio that I purchased there.”

Although business had been booming throughout the ’90s at both locations, an unexpected tragedy struck in August 2001. Plotnik was walking one of his dogs, while on a trip to Los Angeles, when he suffered a brain aneurysm and collapsed. He returned to New York to recover, and his employees closed the L.A. store shortly thereafter. Plotnik is now semi-paralyzed and lives in a nursing home on the Upper West Side. The man who would assume the day-to-day operations of the Greenwich Village location was the store’s manager, Chris Weidner. A middle-aged man with short, white hair and thick-framed glasses, Weidner exudes a classically chilly New York attitude — a benchmark for the store’s employees — often giving curt, standoffish answers to questions from customers and the press alike, refusing all interview requests. Nevertheless, he kept the store running and maintained its lengthy legacy.

Most recently, the store’s interior served as the backdrop to comedian Fred Armisen’s recently retired Saturday Night Live intro, which revolved around a shot of him flipping through albums by Sex Pistols and Style Council, two of his favorite bands. He credits the idea of shooting it there to the show’s photographer, Mary Ellen Matthews, but he says he was no stranger to the store. During his teenage years, which he spent in Valley Stream, Long Island, he and his friend would save up their money to go to the city and buy records. “People would warn me that Bob might be unfriendly,” he says. “But he was always nice with me. I would never go back if I had an unpleasant experience. And in, like, 1987, the store let my friends sell their cassette there on consignment. They were very cool.”

As for his feelings about the fate of the shop, Armisen takes a realistic stance about what it all means. “I’m not going to let that become a tragedy,” he says. “Greenwich Village has always changed. I’m sure there are people from the 1940s or ’50s who also lament their favorite restaurant closing, or their favorite bookstore. And that’s how it is. It’s how it’s always been. As long as we all remember it, those records will always be around.”