Throughout his career, much of the chatter surrounding Floating Points (a.k.a. Sam Shepherd) has had nothing to do with his music. Since 2009, the London producer has built up a reputation as a top-notch DJ while playing a unique combination of obscure funk, soul, jazz, disco, house, boogie, Brazilian, and various left-field oddities. Nevertheless, people — and journalists in particular — can’t seem to stop talking about Shepherd’s other life in the laboratory.

Even though it’s been more than a year since he completed a PhD in neuroscience and epigenetics at University College London, the caricature of an overly intellectual “Dr. Sam” persists. The real-life Shepherd, however, is both incredibly affable and regularly beset by an infectious sort of bubbly enthusiasm. As such, the 29-year-old is prone to occasionally spiraling off into complex tangents about French composer Olivier Messiaen, Bill Withers‘ Adjustments, and rare Buchla synthesizers, among other things, but it’s not as though the guy is too smart to have fun at a party. “The club is designed as a hedonistic environment,” says Shepherd. “I love that space and that experience of letting go.”

At the same time, he contradicts the notion that dance music is only capable of fostering mindless self-indulgence. “I don’t feel like it’s not a stimulating environment,” he explains. “I’ve been lucky enough to be surrounded by people that are extremely smart and really interesting. [Caribou] and [Four Tet], I call these guys every day. They’re some of my best friends… Ben UFO, Pearson Sound, these are all my mates that I hang out with on a weekly basis. They’re blindingly intelligent people.”

Also Read

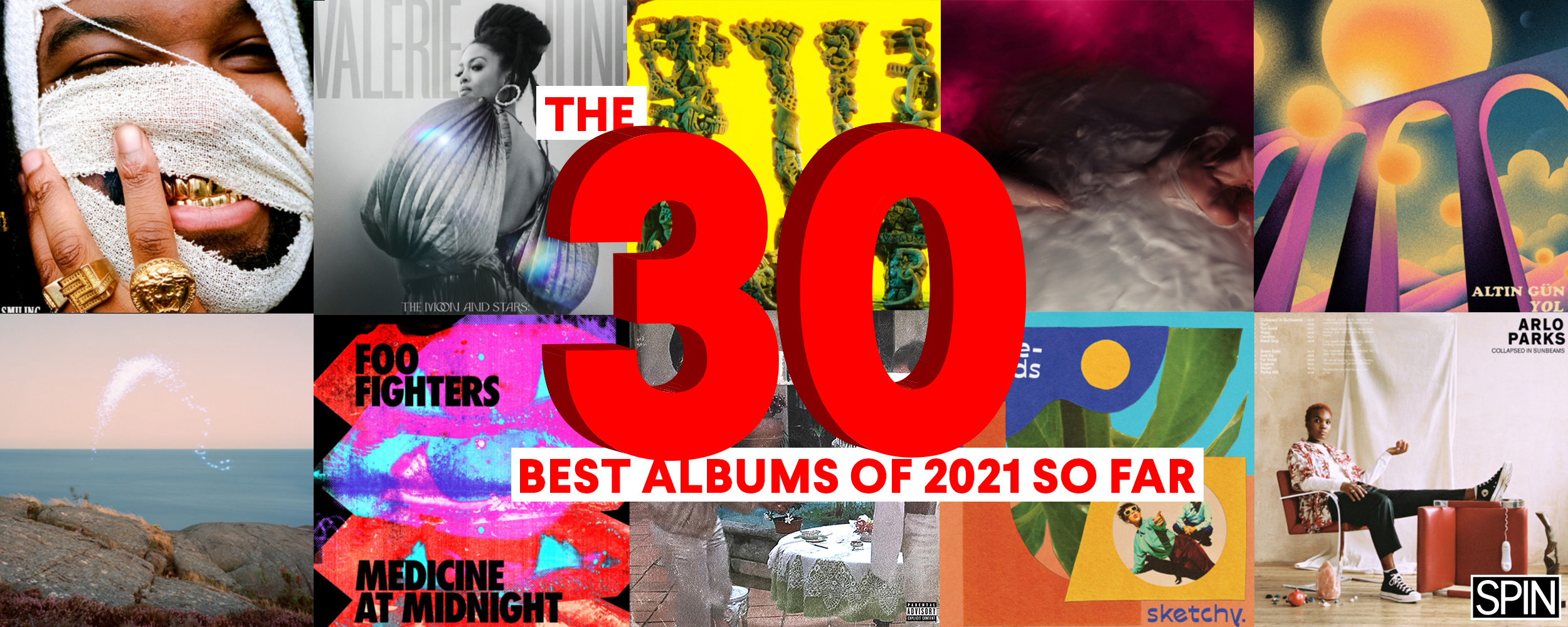

The 30 Best Albums of 2021 (So Far)

Shepherd does still keep up on science journals and pop into his old lab every now and again, but he’s now entirely focused on music and has used the extra free time to complete his long-awaited debut album, Elaenia. Taking its name from a bird that he spotted in a dream, and featuring cover art created by a harmonograph that Shepherd built himself, the LP — which is being released by his newly minted Pluto imprint in the U.K. and the long-running Luaka Bop label in the U.S. — does have an intellectual streak, an effect that’s only compounded by the fact that there isn’t much in the way of DJ-friendly club tracks on the record.

Floating Points has never been synonymous with bangers, but Elaenia is a lush, symphonic record where percussion often takes a back seat. Coming on the heels of 2014’s dance floor-filling “Nuit Sonores” and even the slightly weirder “King Bromeliad”/“Montparnasse” 12-inch, the LP is bound to throw some fans, and Shepherd recognizes that. “I’m not trying to annoy people and say, ‘Don’t consider this a different thing,'” he says, “even though it does sound very, very different.”

In his mind, there are direct parallels between the album and 2011’s Shadows EP, which leaned heavier on percussion (and contained “ARP3,” one of Shepherd’s signature club tracks) but was also populated with clear nods to his extensive jazz and classical background. (Long before he was Floating Points, Shepherd spent many of his childhood years as a chorister at Manchester Cathedral while studying piano and composition at Chetham’s School of Music.)

“It’s a progression,” says Shepherd, “to the point where I have rejected a lot of electronic, purely sequenced events. There are lots more performances of drums and strings.” Such use of live instrumentation recalls his previous work with the Floating Points Ensemble, a literal big band consisting of as many as 16 musicians, many them Shepherd’s childhood friends from music school. They only produced a single record, 2010’s “Post Suite”/“Almost in Profile” ten-inch for Ninja Tune, before collapsing under the sheer weight of the logistics involved. “It was so hard to organize,” says Shepherd. “I was by myself, doing everything. When we did gigs, I’d be doing monitors, doing front of house, and doing tour management… It was a mad shuffle. It was unmanageable, really.”

Nevertheless, his time with the Ensemble prompted Shepherd to get away from writing music on his laptop, a practice he kept up even after the group came to an end. Elaenia does feature a number of guest performers, but Shepherd composed and arranged all of the parts himself. Moreover, he sees the album as the culmination of an effort to unify the various tendrils of his past musical output. “This record,” he says, “I’d like it to all be mixed up together [rather than] separating things out, like, ‘Oh, that’s the classical project, that’s the dance project.'”

“That’s why I dropped the name Ensemble,” he continues. “Just to bring it all back to one place. Even though [the album] has Ensemble vibes, because it’s got strings and stuff in it, it’s very much an electronic record that was made in my studio. It’s a very considered and highly produced record. It wasn’t like I wrote it all and did one session.”

On the contrary, Shepherd took five years to complete Elaenia, during which time he was “chiseling away at it.” Now that it’s finished, though, he’s had to put together a new crew of musicians to take his music on the road. With 11 performers this time around, it’s still a major undertaking, but Shepherd appears to be noticeably less stressed than when it was all essentially a one-man operation. “We’ve got a dedicated sound engineer, a monitor engineer, technicians,” he explains.

The new Floating Points live show debuted in late August at the Dimensions Festival in Croatia, an experience Shepherd describes as both “massively positive” and “great fun.” A short run of tour dates is currently underway, most of which have sold out quickly. In between shows, Shepherd has also kept up his hectic international DJ schedule, which has only intensified in recent years.

Shepherd has never been an obvious candidate for DJ stardom, yet he’s still found success, often by bucking convention. “At Plastic People, I would play a lot of records that I felt belonged in a club that I didn’t necessarily expect people to be dancing to,” he says, referring to the famed intimate London nightspot where he held a monthly residency for five years until it closed last January. He remembers playing Debussy ballads during peak time and recalls, “There were moments where people would just stand and listen.”

Though he’s now regularly tasked with guiding much larger dance floors, Shepherd still likes pushing limits in the DJ booth. With close to 10,000 records in his collection, Shepherd is doing his best to keep his vinyl habit in check and is “obviously getting more critical.” “I’m not just buying records for certain music,” he continues. “Sometimes it’s like, ‘That sound is definitely something I would like to achieve with my own music.’ I buy it for a reference just so I can say, ‘That’s a nice recording, maybe I can emulate that myself.'”

Sometimes he buys a record simply because it’s so interesting he can’t imagine living without it. During a recent trip to Japan, for example, a friend introduced Shepherd to a steel drum and piano record, which he had never heard before. “That, on a musical level I didn’t really need,” he says, “but on a sonic level I was like, ‘I need that so I can hear it again and appreciate that that sound exists.'”

Still, Shepherd has his limits. “Everyone says that Kenny G records are amazing recordings,” he says with a laugh, “but I just can’t get into that stuff, I’m sorry. I love seeing these hi-fi dudes and these crazy hi-fi [systems], and they put a record on and it’s the most abominable Kenny G or something.”

“It’s really not fair and I shouldn’t be saying that,” he continues, “but putting on something that is really well recorded but super questionable is missing the point. People get to that phase where it’s like… ‘I’m going to listen to the worst music just because it sounds so good.’ It’s like, ‘Oh dear, something went wrong.'”