In the very early days, right after we launched the magazine, and as the reality set in we had to do this every month, something which oddly had not occurred to any of us until then, we had a series of panicked editorial meetings. At one, someone brought up Tina Turner, who at the time was probably the biggest pop star in the world. She was everywhere, with her massive hit “What’s Love Got To Do With It,” a film of the same name, and her memoir a bestseller. She had revealed that her estranged husband Ike Turner used to beat her and, frankly, milked that a bit when she was caught up on a tide of universal sympathy. I said, “Everyone’s talking about Tina, let’s find Ike.”

No one knew if Ike was even alive or dead. He had simply vanished from every radar. Ed Kiersh, a brilliant investigative journalist who did several wonderful pieces for SPIN, found him on the uglier streets of Los Angeles, homeless, totally broke, and recently out of prison. Ed’s profile told a complex story of a tortured and ultimately doomed musical genius, who invented Rock ‘n’ Roll with his song “Rocket 88” (about an Oldsmobile). Turner admitted beating his wife, but this story helped define him as more than that man.

— Bob Guccione Jr., founder of SPIN, May 29, 2015

Also Read

THE DAY THE MUSIC DIED

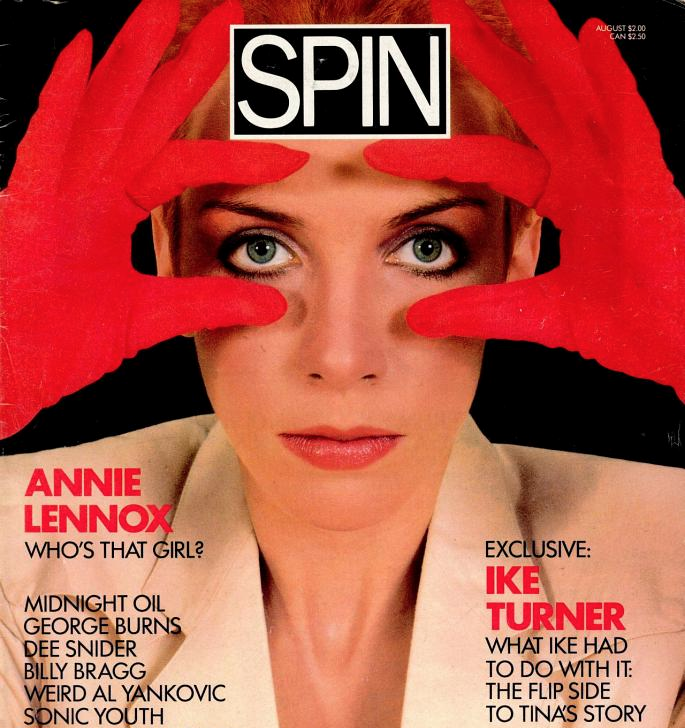

[This story was originally published in the August 1985 issue of SPIN. In honor of SPIN’s 30th anniversary, we’ve republished this piece as part of our ongoing “30 Years, 30 Stories” series.]

The word on the street was that Ike was dead. No one knew for sure, but word was that Ike Turner had met a Hollywood-bad-guy death. Shot — by who? police, dope dealers, a pimp, some dude he owed money; who cared? — the devil himself was gone, apparently. Tina could say whatever she wanted.

Then last December, an item in The Los Angeles Times: Ike Turner contacts Teena Marie about a possible collaboration. “It was to be another Ike and Teena revue,” said Marie’s former manager Allan Mink. “He talked on and on about a national tour, but it didn’t make any sense. He didn’t even leave us a phone number, so afterwards we just laughed. A part of me now feels sorry for the guy.”

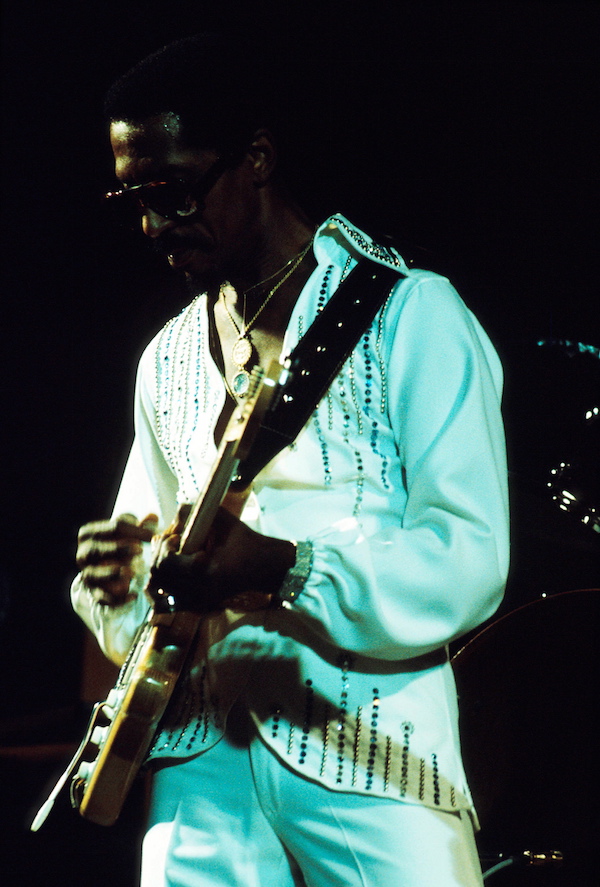

So he wasn’t dead. Instead of meeting an unmourned death in some nameless alley or fleabag L.A. hotel, here was lke, recent Villain of the Piece in the wide-open book of recollections (sort of a Hubby Dearest) — and no patron saint to the California tax people either — making a comeback, or at least reemerging, sort of. The sweet sweetback of rock, who put the S-E-X into Tina’s swagger, who cut what is arguably the first rock record, “Rocket 88,” in 1951; who discovered B.B. King and Little Junior Parker; and who once hired a kid he saw a lot of potential in, Jimi Hendrix by name; Ike, who designed himself into the perfect backup role after he finished designing what was at the time the perfect incarnation of an R&B rock and roll crossover band, had dissolved into, but was not completely obscured by, murky oblivion. If medium-range industry people hadn’t been laughing at him, though, you wouldn’t have noticed even that spark in the fog. Ike was not dead, just forgotten. And not entirely that, either — more like laying very low and trying to be forgotten.

When I started looking for him, I first checked L.A. county jails, because I heard that’s where he was currently residing. The jails didn’t have him. Again, just more mythology, but once again, not implausible: Ike had been arrested and charged five times — for guns, assault, drugs, and most recently, shooting a newsboy in the leg (although the “newsboy” was 49 and had a gun, too) — but he spent only 30 days inside, on the drug rap. He beat everything else.

Then I contacted his old record companies — labels like Kent, United Artists, and EMI (formerly Liberty) — to see if Ike was still collecting royalties. Found, instead, only stonewalls. Quick to remind me that Ike had been off their label for years, spokespeople said they knew nothing about royalties. Their coldness on the telephone spoke volumes: it didn’t matter if Ike was part of the “T’N’T” team that sold millions of records — today he was an outcast, an untouchable. A leper to be kept out of the industry.

Even Paul Krasnow, Elektra’s current chairman of the board, who rose to prominence after producing several Turner albums at Blue Thumb, took a dim view of my search. “Why do you want to do an Ike story?” he asked, in his stylish, charcoal-toned, 21st-floor Manhattan office. “I haven’t heard from Ike in years, and it wouldn’t bother me it a few more years passed.”

Finally, I got my first solid lead. A friend gave me the name of Ike’s New York lawyer, Phillip Cowan. “Isn’t it time Ike told his side of the story?” I asked Cowan. “You’ve seen the articles and interviews with Tina. There wasn’t one word from Ike.” But Cowan was uncooperative. “We’ve gotten dozens of offers for interviews — People, 20/20,” he shot back, “but we’ve turned them all down. Ike’s not doing any press right now. Besides, I couldn’t get in touch with him even if I wanted to. I have to wait ’til he calls me. I don’t even have his number.”

I went to L.A. where I called R&B legend Johnny Otis, who happened to be doing a tribute to Ike on his weekly radio show that evening and invited me to the station. Between playing the cuts “Proud Mary” and “River Deep,” Otis gave me some other contacts. Ike Turner is a very important man in American music,” he said, The texture and flavor of R&B owe a lot to him. He defined how to put the Fender bass into that music. He was a great innovator. I like Ike.”

But Otis, and the dozens of listeners who called in, had only heard rumors about Ike’s present life. No one knew anything else.

Calls to former members of Ike’s band, such as Clifford Solomon, Sam Rhodes, and Bobby John, proved futile. But among the fruitless leads was the story of how Bolic Sound — the “Taj Mahal,” Ike’s studio complex in Inglewood, California — had been torched shortly before he disappeared.

I took my first trip to Inglewood the following day, but before visiting with the police, I stopped at La Brea and Fairview, site of the infamous Taj Mahal, an anonymously given nickname for Turner’s version of the Pleasuredome: his legendary state-of-the-art studio/party headquarters. Today, there are no plaques bearing their silent, stoical testament. Instead, painters were putting the finishing touches on a new office building, and a sign proudly announced the opening of a beauty parlor.

At police headquarters, department officials talked openly about Ike’s run-ins with the law, provided additional contacts, and most important, told me to call the California Fiscal Tax Board, where I discovered that Ike owed the state $12,802 in back taxes for the period 1975-79. According to Will Bush, the board’s PR spokesman, a lien had been placed on his property, and while Bush insisted that debt was sizable enough to justify prosecution, he confidently added, “Turner’s not in California. No way. If he was, we would get him.”

I visited Ike and Tina’s old house, perched on a hill near Ray Charles’s place in a wealthy black enclave called Baldwin Hills; made inquiries at the L.A. Probation Department; and met with more of Turner’s old friends. But no matter who I talked to — Bonnie Bramlett (as a teenager she covered her face with Man-Tan and shimmied onstage as an Ikette in the “ITT” Revue), Joel Bihari, a Memphis band manager Ike worked for, Howard Alperin of Kent Records, even Ike’s old barber, Dwight — the message was always the same. As Alperin emphasized, “Forget it, there’s no finding this guy. He’s a loner, a real elusive type. He could be anywhere.”

After seven days of getting nowhere, I was disgusted. I had a clearer picture of Ike Turner, his character, the contributions he made to rock, and the fast-lane life that led to his downfall. But that was it.

Two days before my scheduled departure from L.A., a friend located Tina’s sister, Eileen Silico. (At a Saturday Night Live party earlier this year, Tina pointedly refused to talk about Ike — and her management people have taken the same stance.) I didn’t expect Eileen to speak too flatteringly about Ike, yet she might know some other Ikettes and other women in the turner constellation.

The seventh time I telephoned Silico, I simply asked, “Don’t you know Vanetta Fields, Robbie Montgomery, and a few other Ikettes? Can you give me their phone numbers?”

“I can’t do that without asking them,” she replied. “That wouldn’t be right.”

Then, without any prompting, Silico added, “why don’t you call Ike’s lawyer, Nate Tabor. He’s in Burbank somewhere.”

It was Friday afternoon. I quickly called, hoping not to lose him. Once Tabor got on the line, he seemed intrigued by my being from New York and only wanted to talk about Steinbrenner’s dismantling of the Yankees. When the conversation finally turned to Ike. Tabor dryly said, Yeah, I have his number. You want to reach him? I’ll get him to call you later today.”

I waited in the hotel room all day. Nothing. It got late. Not wanting to disturb Tabor late at night, I went to bed. There was always tomorrow.

The following morning Tabor wasn’t at home. My phone rang a few times, but each call was only another disappointment. Cursing my luck, I left the room to visit a few boutiques on Melrose Avenue, calling my hotel every hour, but to no avail. The afternoon faded away. I returned to my room about 11 that night, tired and totally disgusted. Then the phone rang.

“I hear from my friends you’ve been looking for me.” The voice was unmistakably southern, yet it smacked of the urban ghetto. His speech was slurred, rapid-fire, and he stuttered. Even without seeing him, I sensed the man was looking over his shoulder as he asked, “What do you want?”

“My magazine wants to do an article on you. I know you haven’t done any press in five years, but everyone’s been slamming the s—t out of you. Why don’t you clear up a few things?”

“I’m not going to talk about Ike and Tina’s sex life — that’s not me.”

After I convinced him that I wasn’t interested in that, his voice mellowed.

“How’s tomorrow at 5? Give me your address, I’ll meet you there… I promise.”

I spent most of the next day wondering if Ike would indeed appear. All week, people had praised Turner for honoring commitments. Clifford Solomon told me, “Ike always lived up to his word. With him you didn’t need a contract — a handshake was good enough. Why, there were times the band would go out on the road and these club owners didn’t pay us our rightful money. Ike always made up the difference. He was a tough son of a bitch to work for, a real perfectionist. But he always looked out for his band. His word was gold.”

Still, I had my doubts, so I waited on the street for him.

At exactly 5 o’clock, a bluish-grey Cadillac Fleetwood pulled to the curb, and a striking, longhaired black woman peered out the passenger-side window.

“Are you Ed?” she asked, as the driver sized me up.

I nodded, and the driver leaned over. Without shaking my hand, he simply said, “I’m Ike.”

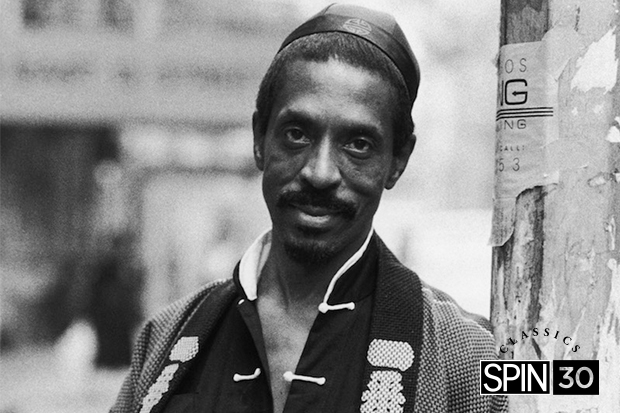

Wearing a white Yohji Yamamoto jumpsuit complete with chest flaps and metal hardware, the goateed, wavy-haired Ike Turner looks like across between a Japanese aviator and Sammy Davis, Jr. We are sitting at a corner table in the Old World Cafe on Sunset. The 54-year-old Turner had been carrying a Louis Vuitton satchel, driving gloves, and Porsche-Carrera sunglasses, but the moment we sat down, he freed his hands for another purpose: to fondle his companion’s thighs under the table. She softly asks him what he’s going to order. Not bothering to look at the menu, he tells her to decide for him.

“I love surrounding myself with beautiful women, I always have,” says Ike. “Tina’s said I always messed around with other women, and that’s true, I wont deny it. If you want to set a trap for me, bait it with pussy — you’ll get me every time.”

Laughing uproariously, Ike kisses the woman’s neck. She chuckles, too. A singer who’s hoping to star in another Ike revue, she gently scolds Ike for not introducing her. Coquettishly closing her cobalt-blue-frosted eyelids and rearranging a tight-fitting blue suede minidress that emphasizes her voluptuous curves, Barbara Cole smiles seductively.

“Ike, baby, I’m gonna get you the shrimp and steak. And how ‘bout a salad and some soup?”

Nodding his head submissively, Ike lights a Salem and stops a waiter to order a few drinks. As Barbara rattles off her dinner requests, Ike rambles on about Tina.

“That woman will say whatever she thinks you want to hear. I don’t care what she says about me, I’ll always be her friend. If the devil was real, it was real… When I saw Tina do ‘What’s Love Got to Do With It?’ I picked up the phone and called her. ‘Hey, Bo [short for Bullock, her maiden name], that’s a cute song. I really like it.’ Well, that was it. I ain’t saw nothing else she did that I like.”

“One time I got pissed off about something I read. I wrote her a letter. ‘Why don’t you talk about you and stop talking about me and the kids.’ I told her she was hurting the kids and embarrassing them. The boys had nothing to do with us.

“But it’s years ago that I had a temper. I don’t regret nothing I’ve ever done, absolutely nothing, man, because it took all of that to make me what I am today — and I love me today, I really do. Yeah, I hit her, but I didn’t hit her more than the average guy beats his wife. The truth is, our life was no different from the guy next door’s. It’s been exaggerated. People buy bad news, dirty news. If she says I abused her, maybe I did.”