Farther down a narrow hallway was another reinforced steel door. Visitors had to punch a secret number into a wall to gain admittance to the master control room — the sanctum sanctorum. There, banks of video screens monitored activities throughout the building, including the cubicles, business office, game room, and upstairs bedrooms, and whatever was happening on the street. Engineers kept watch over the two $100,000 sound boards, with state-of-the-art IBM mix-memorizers, an Even-tide digital delay system, and other flickering gadgetry. It was so Strangelove.

“The place was straight out of Star Trek,” remembers an Inglewood police seargant, after estimating that Bolic contained more than $2 million worth of recording equipment. “Once we into the place, we understood why pimpmobiles were always lining up outside, waiting for people who never came out. Bolic was our neighborhood Disneyland.”

Delaney Bramlett, who regularly visited the studio after splitting with his wife Bonnie, was equally awed by Bolic’s trappings. One of the privileged few with unrestricted access to the upstairs bedrooms and play-dens, he was often asked to rouse the Taj’s Master after an all-nighter. And as he tiptoed past 10-foot-tall Romanesque statues, gold-plated tables, chairs with penis-shaped arms, and murals out of the Kama Sutra, this former country boy had one thought. “The studio was something else; you thought you were in the Arabian Nights, or at least the Waldorf Astoria.”

Presently hoping to make a record with Ike, Delaney for one won’t comment on the bacchanalian scenes that went down in that garish retreat. But Tina Turner, a resident of her ex-husband’s digs, suggests that Ike’s penchant for overhead and braided curtains went beyond mere interior decorating.

Also Read

THE DAY THE MUSIC DIED

Tina simply calls Bolic’s top floor “the whorehouse.” She has pithily described how he moved one of his girlfriends into the studio and stayed at Bolic for weeks at a time after he staged one of his now notorious rampages at home. As these scenes increased from 1974 to 1975, Ike rarely left the Whorehouse to go back to his equally outrageous Baldwin Hills ranch house, with its guitar-shaped table standing beside a waterfall that fell into a living pond filled with exotic Japanese fish. If Ike tired of his lady friend at the time, he’d dismiss her to an adjoining apartment building he owned and find other amusements. The studio was one long walk on the wild side.

“I stopped going there because it seemed like a dope house,” recalls Clifford Solomon, once the bandleader of Ike’s Kings of Rhythm. “Besides the cocaine and other drugs, there were a whole lot of chicks running around. There were so many disreputable people there. Ike had this 357 Magnum on a console in the control room. He was always showing these kinds of things off. The police started to watch the place, and since I had started to work for Ray Charles, the last thing needed was to get busted there.”

“The drugs ate away at Ike,” says Lee Maxie, Ike’s “spiritual counselor” for a number of years. “The cocaine enhanced his being an enemy to himself. He has a special love people, but this love is for selfish reasons. He took advantage of people, especially women. Ike’s a devil. He used drugs for sex purposes. He had a studio filled with women, I’d tell him this was wrong, but he wanted me to meet them. He was friends with this one really famous black singer, and he tried to get me to come over to her house. One Sunday morning he called me over to the studio, and he had the curtains drawn ‘round his big bedroom. It was so embarrassing to hear what was going on. I stepped outside and turned on a sermon I had on this tape recorder I’d brought over. Later, she just sat there, hitting that damn pipe and s—t. A base pipe, cocaine. Freebase. They were hitting it, every son of a bitch there did it.”

Meanwhile, the police maintained their vigil. Ike had already been arrested once at Bolic in early 1974 (along with his business manager Rhonda Graham) and charged with possessing “blue boxes” — multifrequency devices permitting long-distance calls to be made without the knowledge of the phone company. But he had been cleared of the charges. Afterward, the police set up their watch as the limousines came and went from the studio, but could only harass the chauffeurs or ticket Ike’s Mercedes, Lamborghini and custom-made Rolls-Royces.

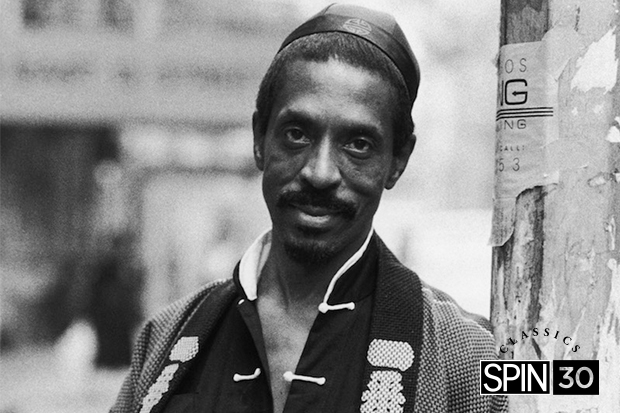

Annie Mae Bullock, the sharecropper’s daughter who became Tina Turner, grew up on the poor side of the tracks in Nutbush, Tennessee. Before there was “What’s Love Got To Do With It?” and “Private Dancer,” and all the monumental — and sentimental — success that accompanied Tina’s triumphal return, there was the Ike and Tina Turner Revue, there were dues to be paid, hard years yielding to better ones, effort yielding success. There was great music and a great act. And there was life with Ike.

Behind the flash, Clifford Solomon recounts, “The band members didn’t like the way Ike treated Tina. He’d hit her, terribly. Her eyes were often blackened. Once, he bought her a dress with bird feathers that he wanted her to wear on TV. She wore it before the show, so Ike was enraged. The next day she was wearing sunglasses.”

Exhausted by these assaults, Ike’s promiscuity, and his mounting use of cocaine, Tina tried to commit suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping pills. As she lay dying in a hospital bed, Ike reportedly called her a “motherfucker” for abandoning the Revue.

“That whole story is one damn lie,” blisters Ike emphatically, grabbing my arm. Other restaurant patrons turn to stare at us. But Ike continues shouting. “I didn’t want go to work that night, and Tina hated doing the show without me. I later changed my mind, and when I walked in, there was Tina with her eyes back in her head. After I found a hospital to admit her, it seemed as if this doctor had stopped working on her, so I said, ‘Hey, Bo, you coward, you chickens—t, if you want to kick the bucket, why didn’t you jump off an overpass.’ I was kidding, I was kidding. I told her, ‘You don’t see me taking the short way out, yet you want me to believe you’re more woman than I am a man.’ I was trying to get her tongue moving. That’s why I don’t like talking to the damn press.”

In 1976, Tina split. And Ike says he “panicked.” “When we broke up I was scared, very scared, because there was no way I could pay those bills. Ike and Tina’s name was always bigger than Ike and Tina. Even with those bills, she could stay home and comb wigs and s—t. Yeah, I was afraid. We had clubs signed up, record deals.”

Gritting his teeth, Ike turns towards Barbara for solace. She vacantly stares back.

“I was scared because at first I thought her leaving wouldn’t be a big thing — she’d come back. I still don’t know why she left me. She even wrote me a letter saying she wanted everything the same, that we’d work together. She didn’t want to mess with the money, anything. I told her no. [After a lengthy pause] I guess she just didn’t want to be named Turner any more.”

The divorce edged Ike to the brink of bankruptcy and gave him his first sour taste of the American legal system. “Tina cries splitting with nothing, but man, her attorneys worked it out so I got all the pink elephants. They had asked me what I needed, and I said, ‘What about half of Anaheim?’ [a 50 percent share of their apartment building]. Instead, they gave me a big mirage, the things that didn’t mean much, like the mortgaged studio, and all of the Ike and Tina royalties from United Artists, which were $1 million in the red. They gave me nothing.”

Embittered, Ike retreated to his studio. Many of his friends deserted him. He surrounded himself with a new set characters. However, the all-night parties that invariably revolved around sex and coke didn’t ease his torment. Not knowing “where my next dollar was coming from,” Ike was going crazy.

“I couldnt believe it. People who were supposed to be my buddies took off,” complains Ike. “For example, this guy Mike Stewart, who was the head United Artists. [now the president of CBS Songs], was always grabbing and hugging when Tina was around. I never heard from that man once when we broke up. Some have been there for me, giving me money when I needed it. But these others, like Bob Krasnow — I made so much money for that man. A few months ago, I called him up and asked to borrow $1,500. Its the only time I ever asked him for something. I’m still waiting to hear from the dude.”

Reminded that his reputation isn’t too savory, Ike looks me straight in the eye, and announces, “I liked coke, who don’t? I’ve always been quiet, but this stuff makes me talk. Before the divorce I was giving the stuff away. I was getting $56,000 a month from one investment alone. Why did I have to sell drugs? When I came to New York I’d set up my hotel room with these big bowls filled with coke in every room, just giving it to people. I didn’t know no better. Man, I was giving away $52,000 worth of s—t every f—king six weeks, ask God.”

In March 1980, the police moved on the Taj Mahal. L.A. narcs, together with a SWAT team, smashed through the front doors. They discovered a live hand grenade and reportedly found Ike hovering over a toilet, surrounded by several empty plastic bags and holding 7 grams of cocaine.

Two weapons charges were quickly dismissed, but a Torrance Superior Court judge ruled that Ike would have to stand trial for possessing cocaine. Initially, it didn’t seem as if the judge was impressed by Ike’s still blemish-free legal record or his legendary musical accomplishments. But at the conclusion of the two-month trial, the judge found Ike guilty, yet only sentenced him to 30 days in the L.A. county jail and three years’ probation.

After that nothing much was heard from Ike. The divorce proceedings had exposed him as a wife beater, and now he was labeled a drug dealer. The heavies in the business stopped coming to Bolic. As activity dropped off there, Ike was forced to sell some of the equipment. The divorce from Tina had left him reeling, financially. Besides losing a three-record deal with United Artists and his share 1.5 million in advance booking in 1975, he was forced to sell several apartment buildings to meet the terms the divorce settlement. Strapped, Ike cancelled a $30,000-a-year insurance policy on Bolic in 1980 and put the property up for sale to fend off foreclosure on a $250,000 loan from a Beverly Hills bank.

“His investments were in such disarray, he didn’t know what he owned,” says Joel Bihari. “He called me after he and Tina split up and asked me to help him with his problems. So my wife and me spent a lot of time at Bolic going through the books to help straighten things out. She discovered that he was a partner in this 380-unit apartment building in Anaheim. We took him out to see it — he had never seen it before. And course he was amazed. It was like he was back in Mississippi. His eyes opened wide, and he said, ‘What’s a spook like me doing owning a place like this?’”

Bolic, though, was Ike’s obsession. “Ike had his cars, maybe a half million dollars’ worth, and three or diamond rings, all of which looked like four ice cubes,” says Clifford Solomon. “But the studio was his first love. That’s where he had put all of his energies.” Around noon on January 20, 1981, as he prepared for a meeting with a group of prospective buyers of the studio, Ike was in his small apartment behind the studio when sirens disrupted the afternoon calm. After rushing into the street to see what the commotion was about, he called his friend Maxie and told him, “You’d better come on down here, the studio’s on fire.”

Smoke billowed from the building for the next 18 hours. According to a fire department investigator, the blaze was clearly a case of arson. It was discovered that someone had poured a flammable fluid along a narrow hallway outside Ike’s bedroom. The fire spread downward, knifing through the sheets of mahogany paneling. Because the studio was such a maze of small rooms and secret passageways, firemen couldn’t reach parts of the building and were forced to watch the building burn until it was nothing more than a gutted shell.