Like every decade, the ’90s had its cathartic heights. And like the ’60s, it seemed like a period in which the culture was moving forward, albeit fitfully, toward a more progressive, enlightened future, at least in our fuzz-pedal-hazy minds. But it was also a decade of repulsive depths, craven money-grabs, and Pauly Shore’s film career. One could make a strong case — and we’ll do so here — that it was actually a cesspool of prissy repression and recklessly moronic freedom that now stands as an embarrassment to one and all. So, we’re here today to finally snuff out your final flicker of nostalgia for the decade that killed Kurt Cobain and allowed Howard Stern to survive, marry a worshipful model, and make $500 million. Hey ’90s, go hump a moose. CHARLES AARON

Eat me, Sebastian: Skid Row bum curses the infirm, attacks fan (1990)

Sometimes a rock star announces to the world that his moment is over in such a colossally clueless way that it feels transformative. Such was the case with Skid Row singer Sebastian Bach, who was caught by a photographer backstage wearing a t-shirt with the proto-Westboro Baptist slogan “AIDS Kills Fags Dead,” which he claims someone handed to him after he took off his own sweat-stained shirt after a Row gig in 1989. Unfortunately for Bach, Revolver magazine subsequently ran the photo, and then Kurt Loder spoke out against Bach’s bozo move on MTV. The singer pleaded poor reading comprehension, but he didn’t help his defense very much when he yukked to MTV: “But let me just state this — I do not know, condone, comprehend, or understand homosexuality in any way, shape, form or [laughs] size.”

Bach also blundered into a shitstorm of bad press when he hit a 17-year-old Massachusetts concert-goer in the face with a bottle and then leapt into the crowd, punching her and another fan (after Bach himself was struck with a bottle), before being dragged back onstage by roadies. He was charged with two counts of assault and battery, two counts of assault with a dangerous weapon, and one count of mayhem. The injured girl was treated for “severe facial cuts and bruises.”

Bizarrely, Bach spent the latter half of the 1990s on Broadway — including, fittingly enough, playing the title role in Jeckyll & Hyde. He also played in a short-lived band called the Last Hard Men with Smashing Pumpkins’ Jimmy Chamberlain, the Breeders’ Kelley Deal, and Jimmy Flemion of Milwaukee’s inscrutable alt-pop provocateurs the Frogs. Coincidentally, the Frogs’ 1989 album It’s Only Right and Natural satirically advocated for a “new gay supremacy movement” in songs like “Dykes Are We” and “Been a Month Since I Had a Man.” PHILIP SHERBURNE

Also Read

Creed Announces 2024 Reunion Tour

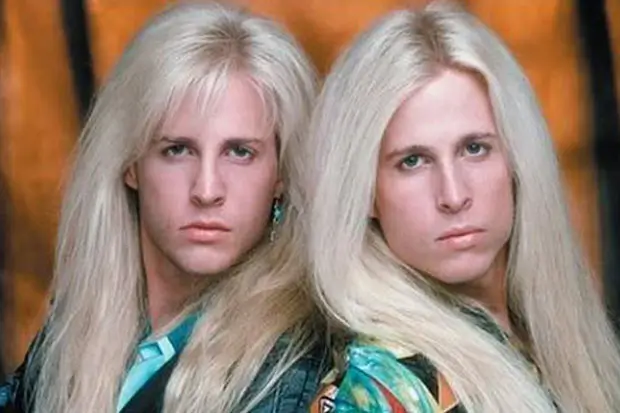

The worst music video of the decade: Nelson’s “After the rain” (1990)

Poodle-pop duo Nelson were the great anomaly in the history of hair metal, because nothing about them remotely scanned as “metal.” Their amps were constructed of Nerf and hummingbird tears. They made White Lion sound like Bathtub Shitter. They looked like a pair of androgynously sexy yeti, and we’re pretty sure their only connection to Headbangers Ball was “having funny-shaped guitars.”

In the year before “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” imagine prolific music-video director Jim Yukich sitting at a table of music-industry execs and pitching this treatment for Nelson’s 1990 hit “After the Rain”: “Okay, check it out, guys, Nelson kidnap a delicate young flower of a boy and transport him to an astral plane where he has a mystical connection with a Native American who hands the twins a magic feather. Afterwards, the only way the delicate young kid can find salvation and peace is by intently watching our young Fabios play tandem guitar on a stage made of rock, while the drummer from Vinnie Vincent Invasion wears sequined bondage overalls. Can I get a couple hundred thou?” In the final version of the clip, a boy from an abusive home seeks solace in Nelson cassettes, and the band whisks him away to their secret world like it’s all a Calgon commercial for shiftless, sensitive teens. Bleached-blonde pretty boys sing to a woman about rebounding after being dumped — that’s what we’re supposed to believe is speaking so deeply to this directionless, dirt-poor 18-year-old with a cruelly unsupportive father. Not, like, Megadeth.

Props to Yukich for having the restraint not to show any actual rain in this video. CHRISTOPHER R. WEINGARTEN

Nintendo’s Power Glove don’t fit (1990)

Remember when virtual reality was going to be a thing? When technology would allow you to inhabit a wholly digital world? When The Lawnmower Man seemed prophetic? The Nintendo Power Glove was the first video-game incarnation of this ineffable promised future. First introduced via the 1989 feature-length Fred Savage and Jenny Lewis(!)-starring Nintendo product-placement flick The Wizard, the Power Glove was the earliest motion-control device for a home-gaming console. (The first PG-specific games arrived a year later.) Unfortunately for the ’90s kids stuck with it, the Glove didn’t control shit: NES favorites like Super Mario Bros., Metroid, and Zelda were rendered nearly unplayable by the Glove’s clunky dysfunctionality. As later, better products like the Wii proved, motion-controlled gaming was a good idea. But the Power Glove’s crass marketing and substandard product made it an example of kiddie-directed corporate greed at its most craven. DAVID MARCHESE

Chuck Berry: Johnny B. very bad (1990)

The man who invented rock’n’roll was an erudite bullshitter with a compromising fetish that he did his best to conceal. But no amount of fast talk could extricate Chuck Berry from the seamy mess he created 35 years after the release of his debut single, “Maybellene.” In December of 1989, Berry bought the Southern Air restaurant in Wentzville, Missouri, his hometown since the 1950s. (He’d once had to buy meals out of the restaurant’s kitchen window during the Jim Crow years.) But trouble soon ensued: An employee named Vincent Huck charged that Berry was transporting large amounts of cocaine in his guitar cases, and based on this tip, Drug Enforcement agents raided Berry’s home, finding no coke, but seizing marijuana, firearms, more than $100,000 in cash, and Berry’s stash of pornographic videos (some of which involved underage girls in sexual poses). Around the same time, a magazine published nude photos — which Berry claimed that Huck had stolen and sold — of Berry and some of his “girlfriends.” Then Huck’s wife alleged that the singer-guitarist had been secretly videotaping women in the ladies room of the Southern Air via a camera hidden in the ceiling. Within months, other supposedly victimized customers joined a class-action suit, while prosecutors attempted to charge Berry with child sexual abuse (since some of the women taped were presumably underage). Eventually, the case collapsed, and all the charges, except for misdemeanor possession, were dropped. The legendary rocker’s legacy, however, was permanently, um, soiled. C.A.

Look how the cat dragged on: the last gasps of hair metal (1990)

Although critical consensus says the ’90s started with “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the decade technically had a 22-month head start. Even if hair metal bands couldn’t see Jane’s Addiction in their rear-views, they should have at least taken some hints from the back-to-basics churn of Guns N’ Roses, Skid Row, and Metallica. By the early ’90s, the last whiffs of AquaNet were being sniffed by the teen populace.

Warrant had a hit video that ganked the title of the most famous anti-slavery book ever (their song was a goofy murder mystery about the town sheriff). Aforementioned duo Nelson — spawned from The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, a living lineage of milquetoast — had three Top 20 singles, all of them love songs, all with the word “love” right in the lyrics. Heart, Damn Yankees, Scorpions, and KISS were grown-ups teasing their hair like Sunset Strip streetwalkers, and all got Top 10 albums for their troubles. Tesla actually called an album Five Man Acoustical Jam and covered the Grateful Dead. Poison did the “Unskinny Bop” with cartoon cowgirls. And all-ballad-everything pin-ups Winger began the decade with a platinum record that was a leather jacket and a distortion pedal away from Don Henley, and became Beavis’ punching bag as a result. C.W.

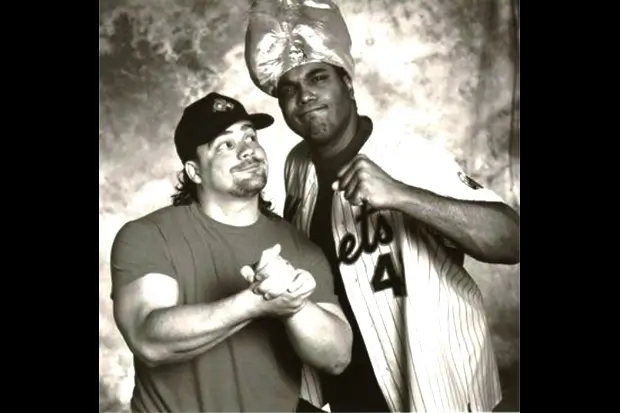

“What’s up, squeaky balls?”: The Jerky Boys (1990)

Prank phone-callers are second only to prop comics on the ladder of least respectably funny people ever, but as a spontaneous underground phenomenon (see the Tube Bar tapes featuring irascible New Jersey bartender “Red”), it provided the occasional, disruptive chortle. But the Jerky Boys — Queens loudmouths “Johnny B” Brennan and turban-wearing Kamal Ahmed — turned the cheap joke-grab into a hot mess of cheesy voice work, half-baked conceits, and a dollop of racism, sexism, and homophobia. Of course, they drew the attention of Howard Stern (whose own “Captain Janks” prank-called ABC anchor Peter Jennings on-air during the O.J. Simpson chaos). The Jerkys somehow released six albums (two certified platinum!) and dropped a truly unwatchable movie before Kamal exited the group, and Johnny B carried on the sad empire all by his lonesome. There is perhaps nothing more ’90s than the 1997 record Jerky Boys 4: Doing away with the act’s familiar veiny-necked, screaming-cartoon imagery, the cover featured a cheap, computer-generated visual of a pool cue and billiard ball with the number “4” on it; the album closed with “Jerk Baby Jerk (Bass Mix).” BRANDON SODERBERG

Backwoods blooze novelty rock (1990)

Unlike similar trends that followed, the goofball indie-blues show bands of the ’90s, though larded with gimmicks and slick with Murrays, were all about playing it earnest amid the shtick (unlike, say, Southern Culture on the Skids, who sang about fried chicken, and then threw legs and thighs into the audience). It seemed that the ante of ridiculousness couldn’t be upped beyond Doo Rag‘s set-up — Thermos Malling’s “drum kit” was made of a beer box, a film reel, and a metal shopping basket, which he played seated inches off the floor, while Bob Log sang into a vacuum-cleaner hose or a pair of internally mic’d hairdryers, slide-screeching along the neck of a supposedly two-dollar thrift-store guitar. But others continued to push the absurdity envelope.

When Log went solo in 1996, he donned jumpsuits that looked like Bea Arthur’s tribute to Evel Knievel, singing about shits ‘n’ tits from inside a sparkly motorcycle helmet rigged with a vintage telephone-handset-as-microphone. Delta 72‘s muttonchopped frontman Gregg Foreman cajoled their audiences to “Get down!” and addressed them as “Ladies and Gentleman,” while sweating through his suit and tie, coming on like a punk trapped in an airport hotel bar. Their Touch and Go cohorts Cash Money became Cash Audio after an onstage bacon-frying routine garnered enough publicity to get the Birdman’s attention, and the label’s lawyer received a cease-and-desist letter. G. Love shucked and jived like a ’50s street musician, sporting white shoes, sideburns, and even rapping a bit. Sub Pop signed Rev. Horton Heat, known for his punkabilly roar and fake-revival sermons. Perhaps these gimmicks and props provided an ironic distancing, while the performers’ earnest revue personas had just enough Elvis-grade cheese to pre-empt any of the criticism that’s followed white-boy bloozemeisters since the Stones. It was all just corniness melded with blues winks that signaled clearly that they loved embodying the music for awhile, but weren’t actually staking any proper claim to it. JESSICA HOPPER

Dr Dre’s woman-punching problem (1990-91)

These days, Andre “Dr. Dre” Young might be known best as a respectable headphones salesman and the dude who keeps us from hearing Detox. But in the ’90s, his remarkable, history-making stretch as a visionary producer ran in parallel to a period when he earned a reputation as a violent abuser of women. The most notorious incident involved Pump It Up! TV host Dee Barnes, over some truly trifling ish: In 1991, after Barnes interviewed Ice Cube, who had recently departed N.W.A, Dr. Dre decided that the group had been disrespected and physically attacked Barnes at a record-release party.

Hip-hop lore commonly refers to the time Dre “slapped” Barnes, with Dre later claiming, “it ain’t no thing — I just threw her through a door.” However, eyewitness reports were grislier, stating that he slammed Barnes against a wall, attempted to throw her down a stairwell, and kicked her in the ribs, before grabbing her hair and punching her in the back of her head as she tried to run away. Barnes sued Dre for nearly $23 million; the case was settled out of court, but the incident remains a lyrical touchstone. Lesser publicized, though, was a 1990 incident in which a drunken Dre allegedly punched a Ruthless Records labelmate, rapper Tairrie B, at the Grammys for refusing to do an Ice Cube-penned track on her album. She was paid off not to discuss the incident, but in later interviews, she would claim that Dr. Dre socked her in the mouth: “Full on. I didn’t go down, so he punched me in the eye.” These certainly weren’t the only instances of artist violence against women during the ’90s, but they remain some of the ugliest and most enduring. JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD

Crown of shit: heroin’s devastating reign (1990-99)

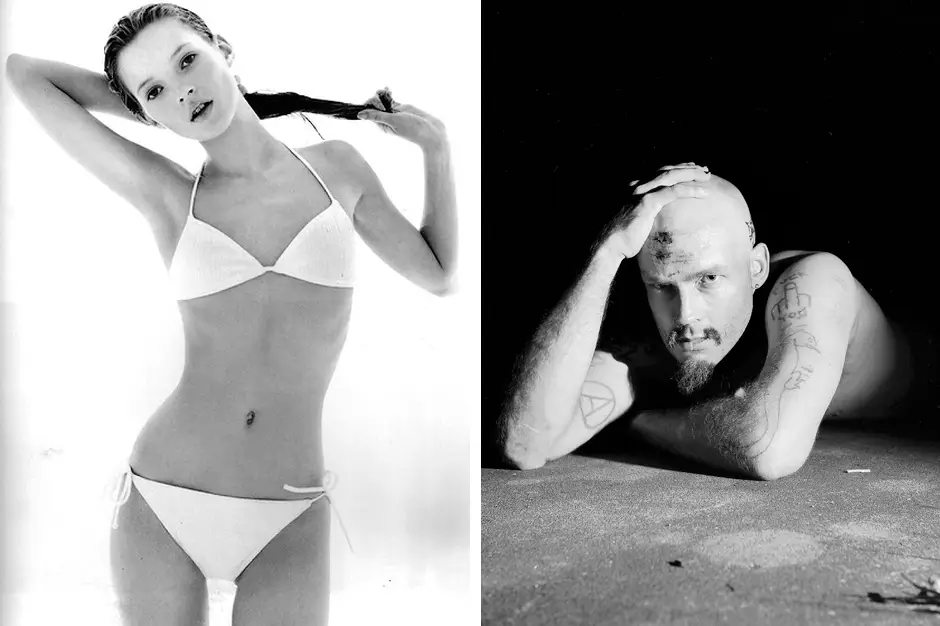

While heroin chic had its waifish posterbabe in the form of Kate Moss and her iconic Calvin Klein underwear ads — all hollow cheeks and jutting hipbones — there was the unchic reality of the absolute prevalence of heroin at every level of the American music scene. Sure, there was Kurt Cobain, the modern martyr, whose suicide was presaged by overdoses both rumoured (after appearing on Saturday Night Live) and reported (a Rome hotel). Everything Cobain co-signed was instantly made cool — even the drug habit that consumed him — but he was just the highest-profile habit around. From 1990-95 alone, here are some of the casualties: Sublime frontman Bradley Nowell, Hole bassist Kristin Pfaff, Unsane drummer Charlie Ondras, 7 Year Bitch guitarist Stefanie Sargent, Mother Love Bone singer Andy Wood, Replacements guitarist Bob Stinson, Skinny Puppy keyboardist Dwayne Goettel, punk shit-slinger GG Allin, Smashing Pumpkins keyboardist Jonathan Melvoin, Flipper bassist John Dougherty, and San Francisco punk lifer Ricky Williams (ex of the Sleepers, Flipper, Crime, and Toiling Midgets). Others’ habits simply made them infamous: See Courtney Love and her life-ruining Vanity Fair interview (1992), Screaming Trees’ Mark Lanegan and his Roskilde stage freak-out (1992), Breeder Kelly Deal’s arrest (1994). Beyond that, in the wake of Cobain’s suicide and other deaths that followed, some folks eventually cleaned up, and some, like Alice in Chains’ Layne Staley, just kept on singing about it till they finally succumbed, too. J.H.

Worst band names of the ’90s (1990-1999)

When a band gets huge enough, it doesn’t really matter what they’re called — the literal meaning of the words falls away. Who thinks of oyster-shell marmalade when pulling Vitalogy off the shelf? Consider it the Banana Republic effect, where a strong brand can transcend even the most ill-considered name. But language, alas, can also hold a far stronger pull than most rockers’ half-baked wordplay. And in the 1990s, band after band bet their hubris against language, and lost.

Perhaps emboldened by the arbitrary imagery that flourished on MTV in the 1980s, the decade’s artists went in hard on phrases that seemed meant to scan as totally random. (That nugget of millennial slang also came into currency in the ’90s, as it happens, turning up in 1995’s Clueless.) Portentous concept names flourished (Darwin’s Waiting Room, Rymes with Orange), and while ravers were sucking on pacifiers, rockers were engaging in baby talk (Goo Goo Dolls). John Hughes’ influence led to any number of band names that sounded like teen comedies (Anything But Joey, Breaking Benjamin, Tabitha’s Secret). Would-be Gutenbergs got clever with their typesetting, as in the cases of Иew Radicals and (həd) p.e. But the most baffling trend in the rock’n’roll nomenclature of the ’90s was bands’ obsession with food. Jam bands were the worst offenders, by far, but even indie rock couldn’t resist getting into food fights now and then: Just consider Archers of Loaf. (There exists another possible connotation for their name, but we don’t even want to go there.)

Our list of the 10 worst band names of the ’90s doesn’t focus exclusively on the culinary category, but food metaphors nevertheless crop up several times. If we had to sum them all up in two words, the review would read thusly: “Shit sandwich.” P.S.

1. Bowling for Soup

2. Alien Ant Farm

3. Leftover Salmon

4. Butt Trumpet

5. Bongzilla

6. Porno for Pyros

7. (Tie) Hootie and the Blowfish/Limp Bizkit

8. Goober and the Peas

9. Snot

10. Bush

A decade in rap censorship (1990-1999)

At times, particularly during the first half of the ’90s, the number of institutional attempts to push back against hip-hop made you think that some sort of power structure was systemically responding to a serious threat. Naaaahhh! That’d be crazy conspiracy talk, right? Anyway, here are some of the decade’s censorship lowlights…

N.W.A Concerts Shut Down by Police (1990): As a result of FBI Assistant Director Mitch Ahlerich’s letter to the group’s label, Ruthless Records, in which he unofficially complained about “Fuck Tha Police” off N.W.A’s debut album Straight Outta Compton, the anti- brutality track was placed at the center of a law-enforcement crusade. Police across the country refused to provide security for concerts, seriously undercutting the group’s ability to tour.

2 Live Crew Obscenity Trial (1990): One year after the release of 2 Live Crew’s As Nasty as They Wanna Be and its hit single, “Me So Horny,” lawyer Jack Thompson (who was affiliated with the American Family Association), Florida governor Bob Martinez, County Circuit Judge Mel Grossman, and Broward County Sheriff Nick Navarro teamed up to get the album declared legally “obscene.” Record-store retailers were arrested for selling Nasty , and 2 Live Crew were arrested for performing. In 1992, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit finally overturned the obscenity decision.

Gingrich Encourages Advertisers to Drop Rap Stations (1991): With politicians launching strongly worded lectures against hip-hop’s degradation of the country’s moral values, House Speaker Newt Gingrich told Broadcasting and Cable magazine that he believed businesses should pull all their ads from radio stations that played rap music. It was a small, public gesture, but it demonstrated how hip-hop soon would be attacked by the intimidation of the money men who backed the music, rather than by outright censorship.

MTV Bans Public Enemy’s “By the Time I Get to Arizona” (1991): On November 6, 1990, Arizona rejected a proposal to create a state holiday for Dr. Martin Luther King. The next year, Public Enemy responded with “By The Time I Get to Arizona,” off their album Apocalypse ’91: The Enemy Strikes Black. The video for the song was a sunbaked noir that featured Public Enemy visiting the Copper State and killing Governor Evan Meacham with a car bomb. The video was played on MTV once before being banned, with little care given to its larger socio-political message.

Bill Clinton’s Sister Souljah Moment (1992): During the 1992 presidential campaign, Bill Clinton spoke out against rapper, author, and activist Sister Souljah, who was quoted in a Washington Post interview suggesting that those inflicting black-on-black violence might kill white people instead. While giving a speech to Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition (who had also invited Souljah to speak), Clinton took a stand, comparing Souljah’s rhetoric to former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke. “Sister Souljah Moment” since has become pundit shorthand for a politician who rejects a perceived member of the fringe in order to court centrist voters.

Body Count’s “Cop Killer” Removed (1992): Ice-T’s 1992 hard-rock project Body Count came to prominence thanks to the vitriolic rant “Cop Killer,” which arrived at a flashpoint moment when it was politically advantageous for white politicians to consistently badmouth hip-hop. Like “Fuck Tha Police,” the song was willfully misread as a call-to-arms against police rather than as a protest against racial profiling and police brutality. Tipper Gore, the reason we have “Parental Advisory” stickers on CDs, compared Ice-T’s rhetoric to Hitler’s; President George H.W. Bush and Vice President Dan Quayle both spoke out against the song, and actor Charlton Heston read the lyrics aloud at a Time Warner shareholders’ meeting. Ultimately, Ice-T removed the song from further pressings of Body Count’s album and released it as a free single.

Tommy Boy Prevented From Releasing Sleeping With the Enemy (1992): Political gangsta rapper Paris’ second full-length featured the controversy-courting combo of “Bush Killa” (about the assassination of the President) and “Coffee, Donuts & Death” (a police-brutality revenge fantasy), as well as an insert photo of the Bay Area rapper hiding behind a tree gripping a Tec-9 as the president spoke. Time Warner, the parent company of Warner Bros., distributor for Paris’ label Tommy Boy, stopped its release. Paris subsequently founded Scarface Records and put out Sleeping With the Enemy himself.

Ice-T Leaves Warner Bros. Over Home Invasion: After “Cop Killer” became a high-profile political football, Warner Bros. was hesitant to release Ice-T’s solo album Home Invasion. Originally slated for November 1992, it was delayed because of the L.A. riots, the presidential election, and an album cover that depicted the Heston and Quayle contingent’s worst nightmare: a white child alone in his room, listening to rap, seemingly infected by the violent lyrics, which conjure up images of robbery and rape. Its release was rescheduled for February 1993. But Ice-T, still frustrated by the “Cop Killer” controversy, and aware that he was fighting a losing battle, eventually left Warner Bros. and released the album with Priority in March of 1993.

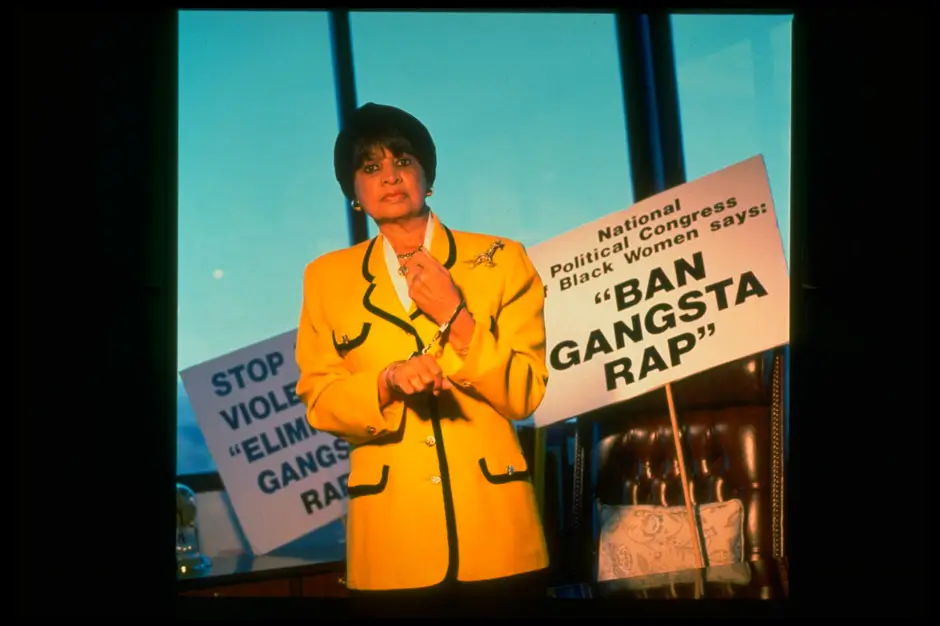

C. Delores Tucker Goes to War with Hip-Hop (1993-94): Activist C. Delores Tucker spent the ’90s grappling with the misogyny and violence in hip-hop: She bought stock in Time Warner, allowing her to protest at shareholder meetings, and thus had a direct impact on the Death Row-affiliated Interscope Records being dropped from the company. Tucker also protested the NAACP giving a 1994 Image Award to Tupac Shakur and would later sue Shakur when the rapper responded on “How Do U Want It?”: “C. Delores Tucker, you’s a motherfucker / Instead of trying to help a nigga, you destroy a brother.”

MTV Bans Hammer’s “Pumps and a Bump” Video (1994): MC Hammer, looking for a bit more edge after the mega-success and subsequent backlash to “U Can’t Touch This,” responded with The Funky Headhunter, and its edgier (and more exploitative) single “Pumps and a Bump.” In the video, he also updated his dance routine with a move that basically consisted of him humping the air in a Speedo, and moving his manhood up and down in what appeared to be an erect state (“Hammer Time,” indeed!). It was pretty much “Elvis on the Ed Sullivan Show” cranked to 11, yet it proved how conservative the country remained about expressions of sexuality.

Insane Clown Posse Dropped from Hollywood Records (1997): ICP’s breakthrough fourth album, The Great Milenko, was originally released by the Disney-owned label Hollywood Records. During the album’s recording, Violent J and Shaggy 2 Dope were told to remove three songs (“Under The Moon,” “Boogie Woogie Wu,” and “The Neden Game”), and to change the lyrics to other songs. The Clowns complied, but within hours of the album hitting shelves, it was still pulled, and the band was dropped. In addition to the questionable lyrics, Disney was still facing protests from religious groups targeting the company for its introduction of the popular “Gay Day” celebration at Disney World. ICP moved to Island and released the album as originally intended.

Eminem Excised from NFL Commercial (1997): At the height of Slim Shady mania, the National Football League released an ad campaign riffing on Eminem’s hit single “My Name Is.” Featuring football legends Joe Gibbs, “Mean” Joe Greene, Joe Montana, and Joe Namath, the “My Name is Joe” ads aired a few times before someone pointed out that the song they were riffing on featured lyrics like, “Since age 12, I felt like I’m someone else / Because I hung my original self from the top bunk with a belt / Got pissed off and ripped Pamela Lee’s tits off / And smacked her so hard I knocked her clothes backwards like Kris Kross.” The NFL legends’ version, of course, did not contain anything even remotely provocative. Still, the ads were pulled, as if even a suggestion of the explicit version was enough to corrupt and offend. B.S.

The war between the sodas (1990-1999)

Few collisions between befuddled consumer and equally befuddled marketer have ever been quite as exhilarating as that of the Great Soft Drink Calamity of the 1990s, a decade littered with short-lived, ill-advised beverage concepts. A year ago, Buzzfeed pointed out that a single can of Surge (RIP) was up for sale on eBay for the hefty sum of $99.99. Inexplicably, there are currently four bottles of the “texturally enhanced alternative” beverage Orbitz (also RIP) available for $60. There is a weathered promotional banner for the world’s first Guarana-laced soft drink, Josta (RIP, party bro), for $80. Or maybe you were more partial to Crystal Pepsi (burp), the mega-brand’s baffling attempt to appeal not so much to alterna-kids but health nuts in search of something more pure, a cola completely free of coloring. A bottle of the diet variety will set you back just 40 bucks at the moment. And at the time of this blurb’s writing, there is a single, unopened can of OK Soda (replete with Daniel Clowes artwork) in “mint condition,” available to you, thirsty “slacker,” for bids starting at $2,900. “Never been opened,” the seller notes. “Not sure what is inside. I can hear something that sounds like coins, I think. No rusts or dents. Extremely rare find.” Sounds about right. DAVID BEVAN

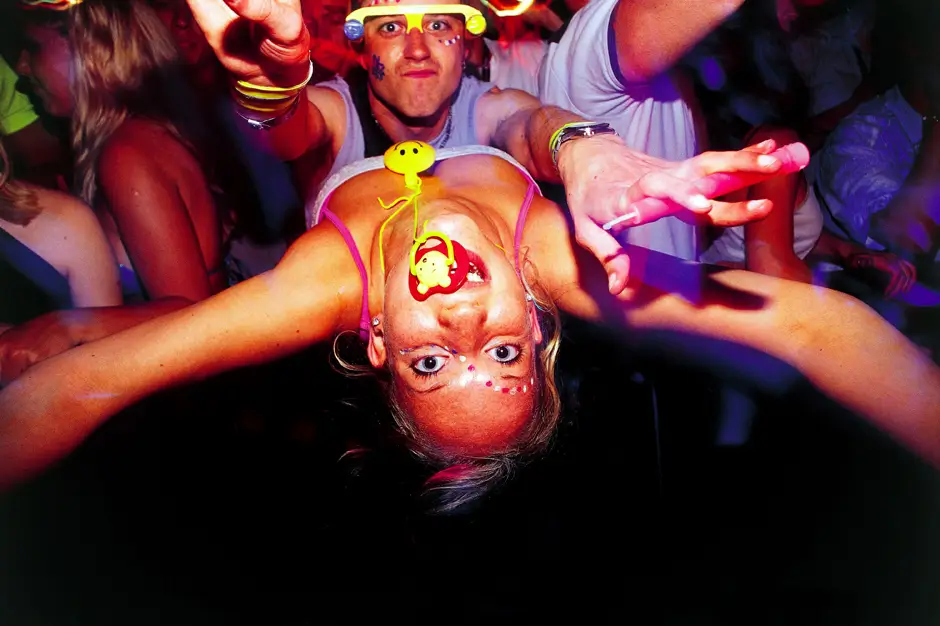

Special K: the floor is hitting my face (1990-1999)

You’re probably already fucked up, and then somebody sprinkles a pink powder on the coffee table, and obviously you snort it, and soon you’re falling, maybe not into a “hole” or anywhere else in particular, but you’re falling, very rapidly, and the room is not really spinning, but dividing itself into cubistic angles that your head keeps banging into, and everything you try and grab to regain your balance atomizes into fluorescent dust and then reforms as a budding flower that tickles your nose, just before shooting off like a blurry comet, only to be replaced by the image of Nikita Kruschev laughing in your face and banging his shoe maniacally like a 60-year-old Dutch gabber kid. And vets give this shit to horses to tranquilize them. Damn, horses are badass.

Yes, for a time during the ’90s, ketamine, a.k.a. Special K, was an extremely popular “club drug”; and while MDMA had been outlawed in 1985, K wasn’t classified under the Controlled Substances Act until 1999. So, yeah. Of course, the shit does have legit therapeutic uses and can alleviate depression in a controlled environment, but during the ’90s, that environment was more likely some skeeve’s grotty flophouse or an abandoned warehouse (or storage unit or barn or under-construction grocery store or disused jungle golf or what-have-you). And as mentioned above, you were probably already fucked up, and some dreamy, sweaty, bug-eyed girl or boy dressed like a giant piece of toast (who would be employed in marketing in 10 years) was trying to get you to dance to Sasha and Digweed. For further info, consult the film Party Monster and heed the sad parable of Macaulay Culkin. C.A.

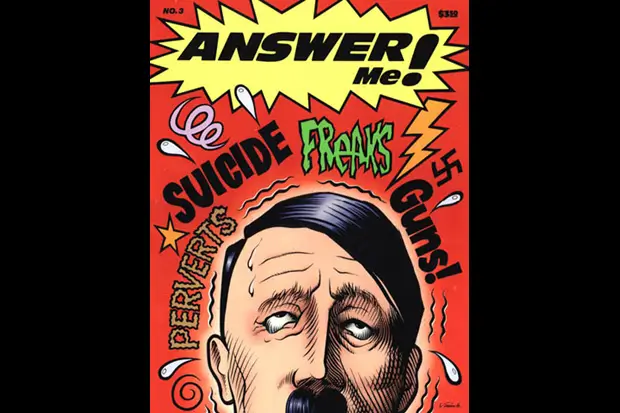

Jim Goad’s Redneck Manifesto (1991)

As the ’90s first revved up, threatened whites who fancied themselves intellectuals and subversives pushed the line that “political correctness” was taking over and impeding free expression. This sentiment ran parallel to punk and D.I.Y. culture becoming more diverse, and no doubt, there were plenty of alienated bros peeved that they now had to consider the points of view of women and minorities. At the top of this contrarian trash heap was infuriated, working-class whiteboy Jim Goad, who created Answer Me!, a fuck-your-feelings, catch-all zine (published from 1991-94) that was fueled by an undeniably ferocious vigor, and mostly consisted of misanthropic, satirical, proto-VICE rants/editorials with titles like “People Ruin Everything” and random bits like prank-calling Dr. Jack Kevorkian. Answer Me!‘s fourth foray was “The Rape Issue,” featuring a battered woman on the cover wearing a nametag that read, “Hi! I asked for it!” and a board game where the goal was to rape a woman. Coupled with the faux-Nazi posturing of Boyd Rice, Shaun Partridge, and other anti-PC gasbags, the whole project seemed more like a proto-Tea Party circle jerk than some noble attack on “good taste.” Goad ended up serving time in prison on assault and kidnapping charges for an incident involving a female Answer Me! reader who became his girlfriend. Assholism would eat itself when he later began contributing to VICE. B.S.

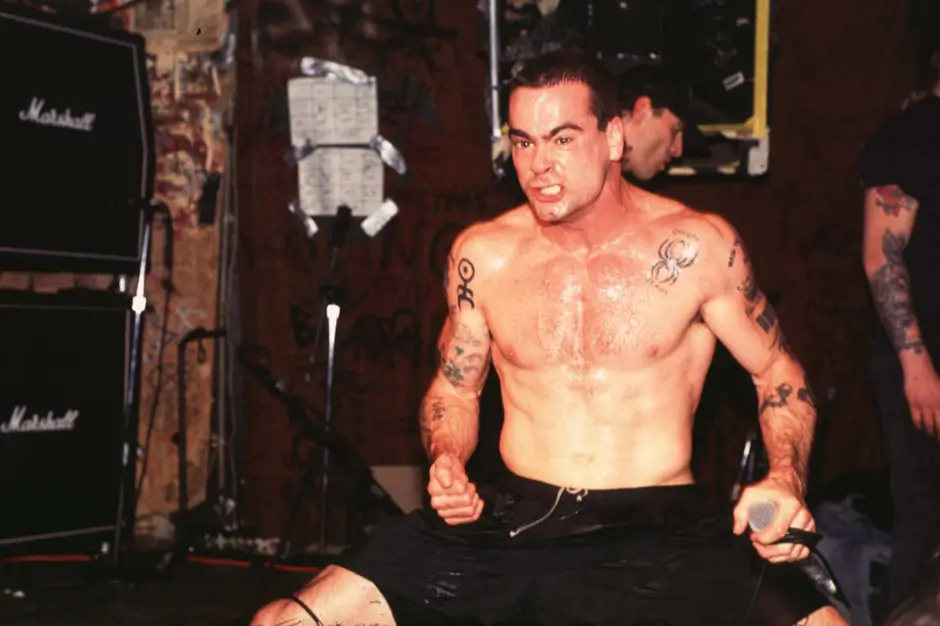

Rollins (1991)

Post-Black Flag, the mucho-macho art rage of Henry Rollins went permanently off-road. Fancying himself a sort of dim-bulb-punk Charles Bukowski, he began self-publishing his overheated journals and rants. In December of 1991, traumatized by the death of his best friend Joe Cole in a struggle with armed robbers, Rollins released a barrage of new material, most notably 1994’s Grammy-winning, double-disc spoken-word album Get in the Van: On the Road With Black Flag (culled from 1986 tour diary Hallucinations of Grandeur). Regarded as something of a rock-literary classic, the gist of the project is “We pulled up to the venue and some hippies laughed at us, so I kicked them down the stairs, blarghhh,” interrupted by all-caps, tough-guy, maybe-on-acid statements about life and struggling, man.

Thankfully, Get in the Van did not contain the grossest story from Delusions, in which Rollins described putting his toe in a woman’s vagina while onstage during a show. But what he spared us in icky details, Rollins made up for with embarrassing ventures like playing a cop in the Charlie Sheen and Kristy Swanson flick The Chase, more and more spoken word, and the Rollins Band, which felt like the Red Hot Chili Peppers running in place for hours on end, minus the melodies. B.S.

Ramanah (1991)

In 1991, founding Pearl Jam members Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament were in search of a singer. They passed along a cassette of instrumental recordings to a friend, Red Hot Chili Pepper drummer Jack Irons, who passed it along to Eddie Vedder, then a gas-station attendant in San Diego. Vedder added some properly anguished vocals, mailed the cassette back up to Seattle, and a few days later, Gossard and Ament heard what the rest of us would end up hearing for the next decade-plus: a chesty, wounded-bear vibrato that would make way for a million more just like it.

So many, in fact, that we now have “Ramanah,” a term to corral, classify, and lampoon them all. Just 13 months after the release of Pearl Jam’s debut, Ten , in August of ’91, the cosmos (or Atlantic, anyway) gave us Scott Weiland and Stone Temple Pilots’ infernally hummable Core. By late 1993, all this pained wailing had inspired an “Operaman” number on Saturday Night Live, not to mention Crash Test Dummies’ “Mmm Mmm Mmm Mmm,” Collective Soul’s “Shine,” and Candlebox’s “Far Behind”; soon, the mainstream was ready for the easy-flowin’ ballcap-bellow of Darius Rucker’s Hootie and the Blowfish, whose Cracked Rear View would go on to sell more copies than any other album in 1995. And though Pearl Jam’s visibility and commercial viability waned dramatically in the decade’s second half, Vedder’s legacy lived on most prominently in the work of Creed frontmessiah Scott Stapp. (Vedder would later use barbed wire to remove Stapp’s larynx in an episode of MTV’s clay-mated series Celebrity Deathmatch, in a desperate attempt to get back his voi-oi-oice.) His efforts were in vain, though, as hacks from Our Lady Peace to Nickelback refused to surrender the Ramanah. D.B.

To the extreme: the bottoming out of pop rap (1991)

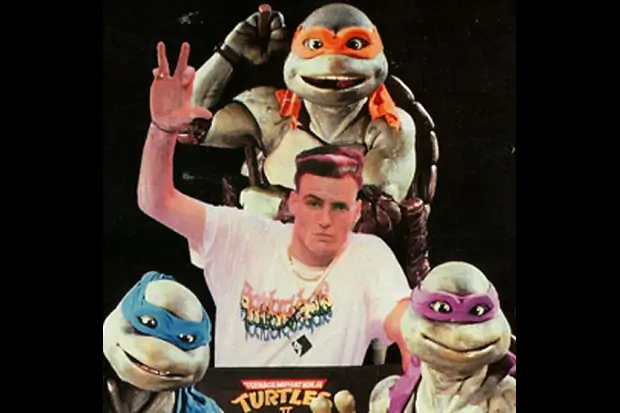

In the summer of 1990, even if you thought the indulgent, springy, sequin-coated Diet Pepsi rap of MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This” and Vanilla Ice’s “Ice, Ice Baby” were soft, those songs were “Fuck tha Police” compared to what came afterwards. Like Elvis and the Fab Four before them, Hammer and Mr. Van Winkle were hustled toward awkward film tie-ins. In his “Addams Groove” video, Hammer gallivanted with the stars of the Addams Family movie, with the clip screening alongside the flick: Hammer slapped five with Thing, mused on Cousin Itt’s dance moves (“He got to wigglin’ and wobblin'”), and had his neck placed in the guillotine by Wednesday. The disembodied Hammer head raps anyway — a better metaphor for the label politics that begat these deals, there is not.

No surprise is the even more shameless route taken by Vanilla Ice, who popped up in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze, performing the shrill, nonsensical “Ninja Rap” at the Dockshore Club, a venue that the reptiles were thrown into even though Leonardo offered some baddies “the traditional pre-fight donut.” A fight sequence happens on the dance floor as an inspired Vanilla freestyles some lyrics: “Yo, it’s the green machine / Gonna rock the town without bein’ seen.” This bogus moment pretty much spelled the end of Ice’s career, maybe because, as the great Tim Dog said later that year, “Rap is not something to be put in movies with a bunch of fucking turtles.” C.W.

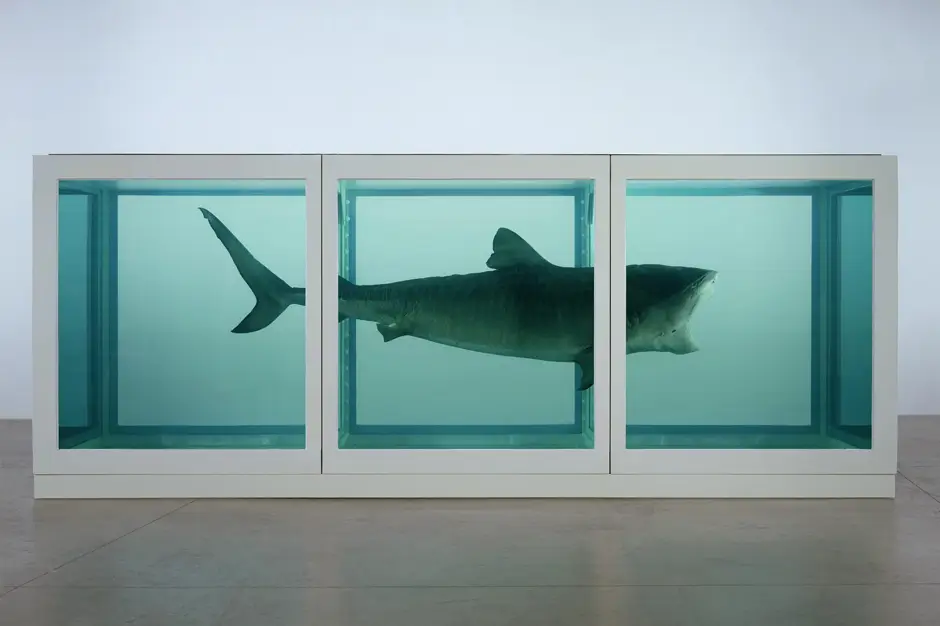

Damien Hirst, Art Superstar (1991)

God forbid some rich asshole has to think about what a piece of art actually means. Damien Hirst, leader of the provocative ’90s crew the Young British Artists (YBAs), saved auction-besotted inflationeers from such a troublesome nuisance by reducing conceptual art to stunt taxidermy, especially with his pathetically iconic 1991 shark-in-a-tank piece The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. The shark was living, and now it’s dead. In a tank. And some nitwit could buy it. No interpretation necessary. The only barrier to ideological entry was the cost, which, naturally, was gross. (The installation went for a reported eight million in 2004.)

At least Hirst developed his kiddie pool-shallow vision honestly. In 1990, he stuck a rotting cow’s head in a box, and let it fester in flies and maggots. There was no deeper statement intended, nor was there in any of his pieces, unless you count this mission statement, uttered by Hirst himself during the ’90s: “I can’t wait to make bad art and get away with it.” Mission accomplished — and it’s almost enough to make you nostalgic for the days when this bozo bothered to make his own work. D.M.

The Spanish version of Right Said Fred’s “I’m too sexy” (1991)

¡Que lástima! C.W.

The positive fluff of pillow-soft rap (1991)

Before they could be appreciated as the feathery-soft progenitors of cloud rap, Windham Hill-hoppers P.M. Dawn were the love object of rock critics and the bête noire of their fellow MCs — KRS-One famously declared, “Outta here” and tossed ’em off the stage at Manhattan nightclub S.O.B.’s. After the psychedelically bedecked duo hit No. 1 with “Set Adrift on Memory Bliss,” labels went tofu-ham, signing similarly minded softballs.

Me Phi Mi got some Buzz Bin buzz thanks to his use of tender 12-string acoustic guitars, a foggy Julien Temple video, and lyrics like “Solar energy within me, all through me / It’s the sun full of light bringing power and might.” The aggressively mellow debut from Spearhead was an organ-heavy, pro-peace, anti-dairy boho move from Michael Franti at the midpoint between his role as Molotov-throwing political rapper and pop-reggae revolutionary. Touchy-Feel rap’s moment was short, but ultimately Diddy and Ma$e realized that P.M. Dawn broke through for their universal ability to “take hits from the ’80s / But don’t it sound so crazy?” C.W.

Functional rave fashion (1991-92)

On the whole, raver fashion in the early ’90s fared better than in the latter half of the decade, as looks devolved from natty U.K. steez (FreshJive/Clobber, loose-fitting overalls) to trashy Euro-and-U.S. candy rave (JNCO, Muppet-fur spats). But the lowest of the low in the oeuvre were two accessories that emerged in the early part of the scene and, to their credit, were a definitive example of fashion as function. Most popular, and still associated with rave culture, were baby pacifiers worn as necklaces — not to freak-up parties with an art vibe, but to curb the teeth-grinding associated with popping dirty ecstasy. Also, when Coco Chanel said that true fashion is about the way we live, she probably wasn’t imagining a society that went out in public wearing surgical masks spiked with Vicks VapoRub meant to heighten the MDMA high. (Although the masks did have a quite lovely, proto-Richard Prince/Sonic Youth/Louis Vuitton appeal.) In retrospect, the copious “Where’s Molly?” t-shirts of today’s “EDM” broscape seem so innocent, so clean. (Bonus ’90s trivia: In Christina Kelly’s scathing review of a London rave in the January ’93 issue of Sassy magazine, she deferred to SPIN‘s own editorial director, then a Sassy staffer, for music advice, writing, “Quick definition of techno courtesy of Staff Boy Charles Aaron: really, really fast electronic dance music that sounds like a video game constantly going off.”) J.E.S.

The four biggest MTV Video Music Awards performance fails (1991-95)

4. Exit Sandman: Metallica’s Unforgivingly Bungled Vocals (1991)

A spirited, hair-whipping, 75-percent-sleeveless Metallica burst out at the ’91 VMAs, present only to bury ballad enthusiasts like Poison and Queensryche, two acts who had the misfortune of opening for the meanest band in MTV’s rotation. But one thing those pretty bands did have on ‘Tallica was clean, polished vocals, as bassist Jason Newsted made pillow-grippingly clear with his dog-howling yowls on “Enter Sandman.”

3. The Leningrad Cowboys Feat. Alexandrov Ensemble Perform “Sweet Home Alabama,” Complete with Balalaika (1994)

Can anyone even remember what the fuck this was all about?

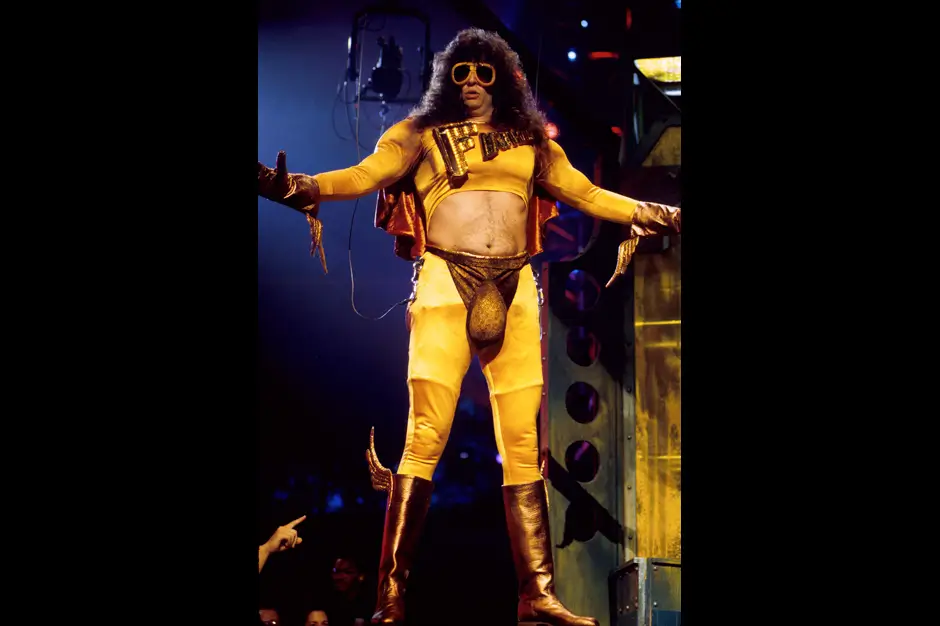

2. Fartman Attacks! (1992)

In 1992, Howard Stern, the “King of all Media,” had yet to figure out how to conquer TV or movies or satellite radio or network talent shows. Attempting to get his movie about a flatulent superhero off the ground, Stern descended from the rafters of the 1992 VMAs as “Fartman,” rudely tooting at the podium, and luring an audience member to touch his bare ass. The “sketch” was so woefully under-developed (mostly Stern proclaiming, “I am Fartman” and “Who of you would like to touch my ass?”) that it took the wind out of his film career for another half-decade.

1. Blunderkiss ’95: White Zombie Experiences Technical Difficulties (1995)

“It’s almost over!” shouted White Zombie frontghoul Rob Zombie, closing out the 1995 VMAs. “And we can go home.” But sadly for White Zombie, they would be astro-creeping out the side door instead of exiting triumphantly. During their performance, the band couldn’t sync up with their backing track on the bludgeoning “More Human Than Human” — it’s safe to assume that drummer John Tempesta couldn’t hear the track at all — and the decade’s best “Immigrant Song” rewrite turned into a trainwreck of a Reichian phasing experiment. C.W.

Courtney Love’s BFFs (1991-1996)

The ’90 brought us the full spectrum of Courtney Love — every shade of her volatile personality. At the dawn of the decade, we got her larger-than-punk, bootstrapping, shrieking ingenue who’s rep in the underground preceded her with then-fledgling band Hole. By 1999, she was Hollywood credible, shacking with a proper movie star (Edward Norton) and hitting her Hotel California stride. Along the way, her image was buffered by her crew. Here’s a power ranking…

1. Kurt Cobain

As Love told Barbara Walters after Cobain’s death, her husband was her best friend, and her entire identity is still based on her relationship to him, as his Yoko-muse and, later, as his widow.

2. Drew Barrymore

During the mid-’90s, when Barrymore was hot from a Playboy spread (plus the weird novelty of her being an adult), she dated Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson, and as Love was listing toward Hollywood, the two became official gal pals. Inseparable blonde trouble, omnipresently making the scene, they upped each other’s ante. The two were so tight that Frances Bean Cobain was the flower girl at Barrymore’s quickie wedding to Canadian comic Tom Green.

3. Kim and Thurston

Kim Gordon co-produced Hole’s debut, giving the band cool cred from the jump. Sonic Youth brought Hole out on their Goo tour, and Thurston blabbed to the British press about the mercurial Love, lumping her in with a women-in-rock trend he dubbed “Foxcore.”

4. Milos Forman

The Greek film director offered Love her most direct shot at procuring credit in the straight world — a starring role alongside Jim Carrey in The People Vs. Larry Flynt — but only if she remained sober. Love did just that, and the film earned her a Golden Globe nomination, plus a few good years of red-carpet action and an air of polished sanity.

5. Madonna

Love boasted to Vanity Fair that Madonna had courted her friendship and tried to recruit her into a punk band that Madge was starting — which Madonna later refuted by asking, “Who is Courtney Love?” The Madonna connection was Love’s way of proving that she’d entered the pop lexicon. She would later prove that Madge knew damn well who she was during an on-air incident during the 1995 VMAs, where Love whipped a make-up compact at the singer and Kurt Loder, then bumrushed the interview, embarrassing everyone involved.

6. Billy Corgan

The two were an item prior to Love connecting with Cobain (when Hole opened a Smashing Pumpkins tour), and are rumored to have had some on-off connections. By the end of the ’90s, though, Love had roped Corgan into a more significant role — he served as co-writer of five songs on 1998’s Celebrity Skin.

7. Kate Moss

Grunge chic’s two biggest icons were good friends, though Love disclosed to a British tabloid that during a Milan fashion week in the mid ’90s, they were actually “more than friends.”

8. Michael Stipe

Serving as godfather to Frances Bean, Stipe came into the Love-Cobain fold early on, and has seemingly stayed by her side ever since; he was a constant companion amid the aftermath of Cobain’s suicide. Early in her relationship, Love all but offered her boyfriend to the R.E.M. frontman, though she insisted it was merely an attempt to call Kurt’s public bisexuality bluff.

9. Amanda DeCadenet

Love and the former Mrs. John Taylor and British chat-show icon were inseparable for a stretch circa 1995, appearing in matching white silk slips and rhinestone tiaras at the Oscars that year. DeCadenet’s friendship gave Love instant name recognition Stateside and in the U.K. for something other than her marriage to Cobain, and provided her with Hollywood A-list access.

10. Trent Reznor

After a short-lived affair while their bands were on tour together, Love kissed and dished this bon mot: “More like Two Inch Nails.” In return, Reznor denied knowing Love biblically, calling her a manipulator and a careerist. Love had the last word, observing to Vanity Fair of their dalliance, “I was slumming.” J.H.

The LAPD (1991-99)

What deplorable thing didn’t the Los Angeles Police Department do in the ’90s? The 1991 Rodney King beating was just the most visible instance of rampant racial profiling and police brutality, and only one of the reasons why the city exploded after the officers — caught on tape violently assaulting an unarmed black man after a car chase — were acquitted. It was what N.W.A had been rapping about for years, so they became the unofficial soundtrack to the unrest as South Central burned and the LAPD disappeared. There was also, of course, their bumbling of (and alleged involvement in) the murder of Biggie Smalls, an incident that was just one of many that spotlighted widespread police corruption as gang violence grew. When poor black and Latino communities weren’t being racially targeted, they were all but abandoned. J.E.S.

The Jim Rose circus (1992)

The commodification of subcultures was an annoying running narrative of the ’90s, and the barnstorming Jim Rose Circus jacked up that process with more raging meathead bravado than most. By utilizing, quite literally, the oldest tricks in the huckster’s handbook — and ones that were revived with more playfulness and less gross-out extremism both before (Coney Island’s Sideshows by the Seashore) and after (Bindlestiff Family Cirkus) — Rose gloried in his role as the Perry Farrell of theatrical self-mutilation, more adept at brand management than creating anything original or shocking. His retinue of performers — the Amazing Mister Lifto (he of the tensile scrotum), Bebe the Circus Queen (she of the bed of nails), plus an array of others (the Torture King, Slug, Matt “the Tube” Crowley) — disgustingly repackaged what geeks and freaks had been hawking for decades (sword swallowing, fire-eating, sleight-of-hand, etc.).

Rose and Co. found the perfect mark in an “alt”-besotted mainstream — the troupe blew up after playing Lollapalooza’s second stage in 1992 —ready for a frat-style initiation into pseudo-masochism. One notorious story had three “groupies” submitting to enemas and then competing to see who could keep from spraying their insides into bowls of Fruit Loops (supposedly held by Marilyn Manson). After one girl finally released her load into a bowl, Mr. Lifto walked up and ate the cereal. Subversive? Nah. Repulsive and opportunistic? Bingo! You know why carnies have to keep moving from town to town? Because they’re con artists. By ’98, Rose was hawking chainsaw football and Mexican-wrestling transvestites who faced off with giant purple dildos; cops in Lubbock, Texas, shut down one show, giving Rose a chance to crow about “redneck hillbillies” and throw around the word “Nazi.”. The fact that the ringleader has regularly dipped into PR consulting work during the past decade is proof enough of his barker’s bluster. D.M.

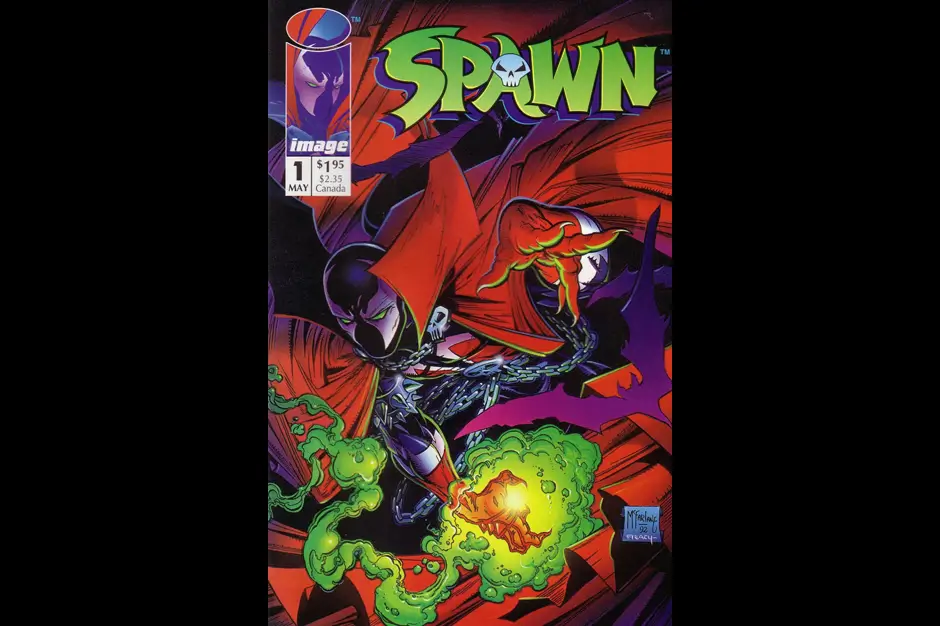

Toddler Todd takes over: image comics panders to the kids (1992)

In the late 1980s, buttressed by a black-and-white self-publishing comics boom and the vitality of sophisticated post-underground work like that featured in RAW, mainstream comics got a little gritty: Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns took superheroes and gave them real-world neuroses, positioning them as bullies and brats. It seems obvious now, but that says more about how internalized those artists’ deconstructive tics have become to comics storytelling. Soon after, though, everything got grittier and darker, and nowhere was that more apparent than at Image, a company lead by Marvel Comics’ rock-star artists Todd McFarlane and Rob Liefeld. They created their own original characters — who looked like their old characters (only now they would own the rights, not Marvel) — and engorged the men with muscles on top of muscles and afforded the women impossibly skinny waists and disturbingly large breasts, all while paying little attention to storyline. The comics were unreadable and rushed, each page something for teens to hang on their wall and nothing more, but it didn’t matter, because they were all adorned with “Ooh shiny” holographic covers and speculating, collector-bait, limited-edition numbering. A true nadir for comic books. B.S.

Who let the pogs out? (1992)

In case you don’t remember how one “played” Pog: You threw a thick round piece of plastic (a “slammer”) against thinner pieces of cardboard. If the Pog flipped over, you kept it. If it didn’t, your opponent got to try and slam yours. That’s pretty much it. Originating in Hawaii before spreading to the continental United States and then the world, Pog was banned in some schools when greedy kids would refuse to return the discs they’d won. But if Pogs were lost, Pogs had to be regained. So McDonald’s, Burger King, Taco Bell, and other fast-food chains began to give away Pogs away with their meals. And to further infect younglings with the gimme gimmes, Pog manufacturers adorned the toys with images of Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, Hot Wheels, WWF Wrestlers, and other fad-inducers in an effort to imbue, let’s repeat, pieces of cardboard meant to be destroyed with phony collectability. Other ’90s kids blips like Beanie Babies, Tamagotchis, and Magic: The Gathering looked like the height of human achievement when compared with this crap, which at its root, was nothing more than “extreme” Tiddlywinks. D.M.

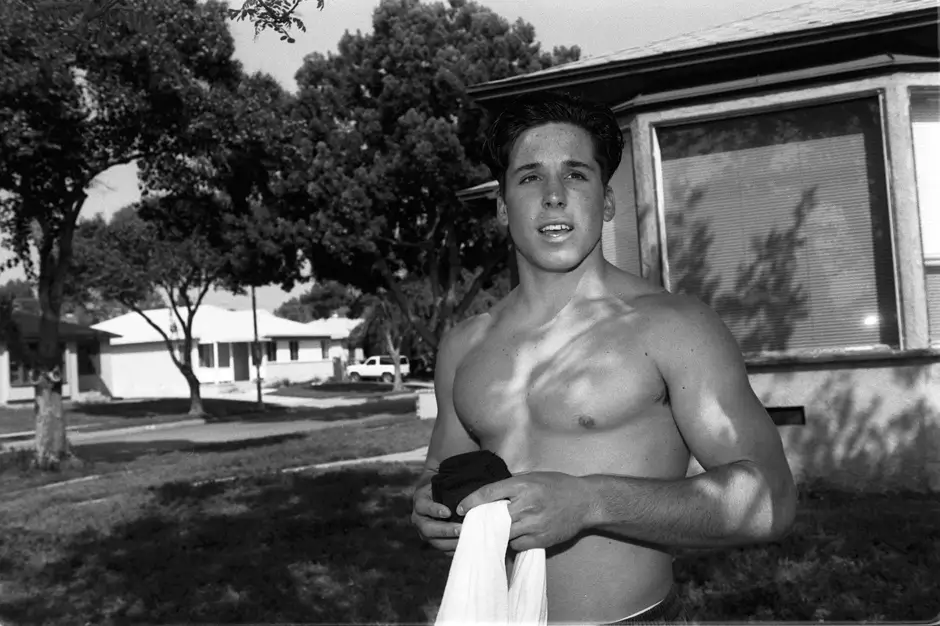

The Spur Posse (1993)

The so-called “Spur Posse” was a group of nine teenage boys from the Los Angeles suburb of Lakewood, California, who named themselves after the San Antonio Spurs when David Robinson, a favorite player of a group member, signed with the NBA team. They were the star athletes of a close-knit community, beefy white jocks who had alpha’d their way through high school, but in 1993, they were shockingly arrested for multiple counts of rape, molestation, and lewd and lascivious acts. It was subsequently learned that they had formed a sex club in which they would accrue “points” for how many girls they were with, consensually or not. Most of the girls were underage (one as young as 10), and some of the rape charges were statutory.

Typically, some of the parents rampaged about how the girls their sons had been accused of raping were “promiscuous” aggressors, amplifying the misogyny in an already misogynistic case — the boys even threatened some of the girls and witnesses about testifying. Eventually, most of the charges were dropped, and the boys were allowed to hit the talk-show circuit. In the New York Times, Anna Quindlen wrote that the “lowlife band of high-school jocks” had “treated girls like garbage while they were passing them around and trashing them afterwards”. And admonishing the slew of television networks putting them on, she added, “The girls get called sluts. And the boys get flown first-class to some big city to brag on national television, the electronic-age version of standing around in the locker room talking about what a pig she was. People always blame the girl; she should have said no. A monosyllable, but conventional wisdom has always been that boys can’t manage it.” J.E.S.

Marilyn Manson grosses himself out (1994)

Since we’re talking about a guy who has admitted to smoking human bones that he stole from a cemetery, it’s hard to imagine that Brian “Marilyn Manson” Warner, the Florida-bred struggle rocker, could do anything that he felt crossed the line of improper behavior. But just such a moment, chronicled in Neil Strauss and Manson’s Long Hard Road Out of Hell, perfectly captured the vile, amoral emptiness at the core of Manson’s persona (and demonstrated why he should be henceforth forgotten as a cultural figure of any relevance).

In short, Manson and Trent Reznor and members of both Manson’s and Nine Inch Nails’ crews were at a Miami recording studio when a fan Manson had invited over, a deaf girl, showed up. Manson commanded her to take off her clothes, which she did, being a “flawless lip-reader,” and he and Reznor proceed to cover her with pieces of uncooked meat — ham, bacon, salami, sausage links, bologna, etc. After documenting these “meat shenanigans” via photo and video, Manson ordered his minions Twiggy and Pogo to tape their penises together and “see if she could put the two penises in her mouth at the same time.” But that didn’t work, so “so they had to face their dicks front-to-front and… She sort of licked it like some sort of dick harmonica.” Things soon escalated to Pogo having anal sex with the girl, who was wearing a leash that Pogo held while shouting obscenities at her. It’s at this point in the story that Manson actually paused and thought of editing out something “offensive;” but he soldiered on. “[Pogo] shouted, ‘I’m going to come in your useless ear canal!’ and it seemed to echo through the room as maybe the darkest thing we had ever heard.” Of course, Manson and Twiggy still peed on the girl while she was taking a shower, and then tossed a large, raw salmon at her. But at least they kinda felt bad about it. C.A.

Regulators, mount up: MTV censorship hip-hopcrisy (1994)

In 1994, the music industry was still reeling from the coup of The Chronic, turning rap’s ganja-and-gun gangsta nihilism into the most popular music on the planet. But offering even more proof that he was the savviest operator in the industry, Dr. Dre recorded equally dope clean versions of his singles like “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang.” Meanwhile, hip-hop staple Def Jam, still scrambling to address the fact that the West Coast had been eating their lunch all year, delivered Warren G and Nate Dogg’s retaliation tale “Regulate” to MTV, whose censors promptly turned it into swiss cheese. Some lines that the late great crooner Nate Dogg couldn’t say on TV: “Nate Dogg is about to make some bodies turn cold” and “I let my gat explode.”

This policy would’ve made a lot more sense if Def Jam ex-pat Rich Rubin hadn’t helped Johnny Cash wage a cool comeback on MTV with the completely unedited lead single “Delia’s Gone” the exact same year. Cash’s tune featured lyrics that might’ve given the Geto Boys pause: “First time I shot her, I shot her in the side / Hard to watch her suffer, but with the second shot she died.” Worst of all was that you could do a side-by-side comparison of the same sentiment in each song: Nate Dogg’s “I best pull out my strap” (edited by MTV) vs. Cash’s “make me want to grab my submachine” (unedited by MTV). C.W.

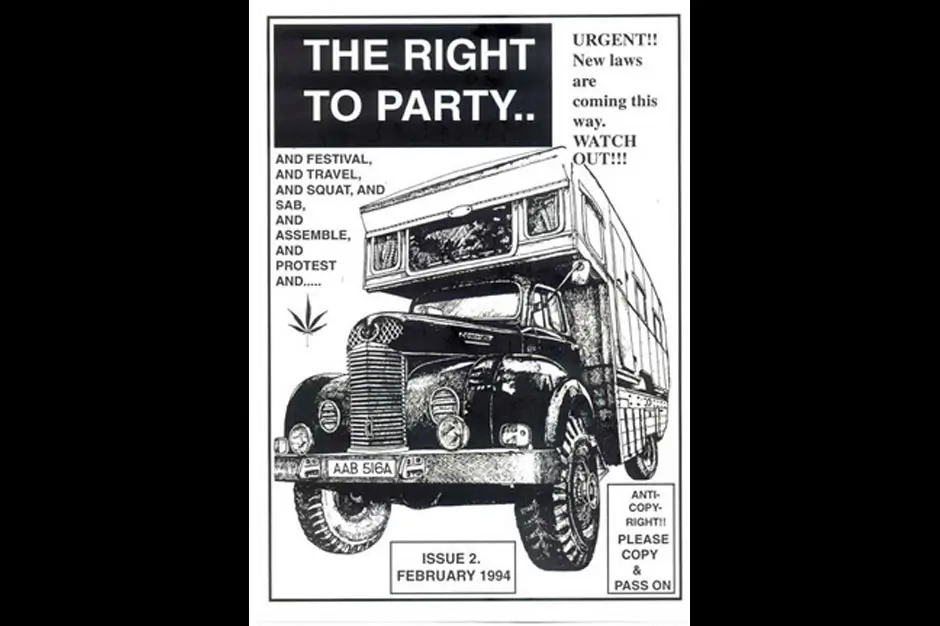

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (1994)

Governments are bad at a lot of things, but when it comes to musicology, they’re hopeless — the whole point of that beating-the-drum-of-liberty thing was to let the drummers choose their own time signatures, no? But that’s exactly what Britain’s Parliament didn’t do when it passed the Criminal Justice and Public Order act on November 3, 1994. The most contentious section of this sweeping legislation was Part V, “Public Order: Collective Trespass or Nuisance on Land,” which was aimed at cracking down on squatters, the itinerant “traveler” movement, and all manner of raves and renegade parties. Lawmakers and hand-wringing citizens had been fuming about the menace posed by the free party movement since spring 1992, when an estimated 20,000 crusties, ravers, and unwashed types descended upon Castlemorton Common for a six-day party. With an entire section dedicated to “Powers in relation to raves,” the Pub Order act granted police the power to confiscate sound systems, harass small groups of people suspected of setting up raves, and turn back suspected party-goers within a one-mile radius of any offending site. But the law’s most audacious provision threatened to criminalize musical form itself, defining a rave as a gathering of as few as 100 people playing amplified music “wholly or predominantly characterized by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” (Perhaps lawmakers were responding to the Castlemorton neighbor who complained to a local newspaper, “There’s something hypnotic about the continuous pounding beat of the music, and it’s driving people living in the front line into a frenzy.”)

The act’s passage quashed the free party scene, sending rave culture overground and, as The Guardian argued in 2009, paving the way for the increasing criminalization of protest in the U.K. Fortunately, the bill never managed to put the kibosh on four-to-the-floor beats, although it did inspire an ingenious protest from Autechre, whose Anti EP was affixed with this warning sticker: “Warning. ‘Lost’ and ‘Djarum’ contain repetitive beats. We advise you not to play these tracks if the Criminal Justice Bill becomes law. ‘Flutter’ has been programmed in such a way that no bars contain identical beats and can therefore be played under the proposed new law. However, we advise DJs to have a lawyer and a musicologist present at all times to confirm the non-repetitive nature of the music in the event of police harassment.” Who knows? Without the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, they might have ended up making tech house. P.S.

The (alleged) romantic entanglements of Adam Duritz (1994-present)

The maddening phenomenon of rock stars punching way above their weight class romance-wise is as old as, oh, Beethoven probably, but aside from the unholy union of Dave Pirner and Winona Ryder (which set a dizzyingly high bar for the Buzz Bin years), the most vexing question of the decade remains: What in blue blazes accounts for the black book of Counting Crows mewler Adam Duritz? Nicole Kidman! Emmy Rossum! Christina Applegate! Mary Louise Parker! Ah yes, and two thirds of the female cast of Friends!

That he now spends a goodly amount of time coyly denying these dalliances (here he is describing Applegate as “my landlord”) only makes their mere possibility all the more enraging. Does the key to attracting scores of famous, beautiful women really involve packing your albums with insomnia and narcissism imagery (see 1996’s Recovering the Satellites) while cultivating a Rastafarian-librarian hairstyle that looks Photoshopped even when viewed in person? When everybody loves you, aw son, it’s just about as funky as you can be. ROB HARVILLA

The Jock Jams commercial (1995)

A spin-off of the profitable Jock Rock partnership between ESPN and Tommy Boy Records (compilations of songs already being played at sporting events), Jock Jams was an attempt to assemble more “contemporary” hand-waving, foot-stomping tracks. The result was an assault of pop-dance synth pummelers that had never been played at sporting events until Jock Jams appeared. Be all that as it may (AND IT MAAAY!!!), the franchise’s most impactful element was its relentless TV commercials, which featured sharply angled shots of gyrating cheerleaders and blaring catchphrases that imprinted themselves on the consciousness of any sentient ’90s mammal: “Pump up the jam!” “Whoomp! There it is!” “I Like to move it move it!” “Jump everybody jump everybody jump!” Of course, the quintessential Jock Jams anthem was 2 Unlimited’s “Get Ready for This,” the ubiquity of which cannot be overestimated. It was basically the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” of roid-raging bros in tank tops getting their swerve on (in the parlance of the time). And it provided enough royalties for the Belgian duo who created it to buy, say, a professional cycling team. Also: There were five volumes of this crap, including an “All-Star” version and a megamix. Hey, San Jose Sharks fans, GET READY FOR THIS! C.A.

Thin white duds: Duran Duran lose the plot (1995)

Duran Duran’s 1995 album Thank You, a covers album featuring their takes on Bob Dylan, The Velvet Underground, Public Enemy, and others, was intended to showcase the group’s impeccable, wide-ranging, genre-hopping taste. It also seemed to be an aging group’s response to their early reputation for nothing more than good looks and rakish style. Few cared to celebrate their game-changing music videos, or the fact that they merged jagged post-punk riffage and repetition with Nile Rodgers and Chic’s blurry, funked-out ease, taking it to the top of the charts. But Thank You only served to make them look silly, awkward, and out of their depth.

Most appalling is the 1983 anti-drug track “White Lines (Don’t Do It),” originally by Grandmaster Melle Mel. Though there’s something admirably cheeky about an ’80s band known for their problems with the white stuff taking on this rap classic, it’s an unmitigated disaster. Namely because it’s a rap song now spit by Simon LeBon, but also because it has ringing sub-U2 guitar riffs in place of those loping Liquid Liquid bass lines, and a chugging, already out-of-date early-90s acid-house pop tug. There are worse things to be be known for than being cute, super-successful New Wave art-rockers. After the falling-on-their-pretty-faces Thank You, let’s hope Duran Duran finally realized that. B.S.

The understandably forgotten history of indie remixes (1995)

Though indie rock had flirted with remixes before — lo, who could forget Coldcut’s 1992 remix of They Might Be Giants’ “The Lion Sleeps Tonight”? — it took Tortoise and the dawn of post-rock circa 1995 to push the things into floridly pretentious ubiquity. (Who knew a fusiony jazz-funk band could have such cultural capital?) Indie’s big names began dropping remix EPs and 12-inches on the heels of albums, and while they often were not the sort of thing anyone would dance to or put on in ze club — remixes were a sign of a cultural seachange, with rockers slowly shedding their crimson-faced shame about dancing. It was now almost-okay to like and be influenced by more than stiff crybaby guitar music.

The mainstream was changing, and the influence of Aphex Twin, the Orb, Tricky, and Goldie were trickling down, but it was rare that indie bands hired a brand-name producer for the task, or even someone acquainted with the laws of the dance floor. No, the remixing tasks were usually parsed out to friends, dabblers, and approximators, which meant tepid dissection more than creative reconstruction. For beat-centric groups like Stereolab, Cibo Matto, and Pizzicato Five, disco seasoning was the common go-to move. But what you wound up with most of the time were things like Unrest’s Mark Robinson turning a Butterglory song into fluttery, hiccuping electrotwaddle that wouldn’t startle a hushed wine bar (Merge 100 Remix EP, waddup!). Yo La Tengo, Tortoise, and the Sea and Cake all dropped proper remix EPs, emboldening the twee likes of the Pastels, Cornelius, and the Swirlies to go hard with full albums of bad ideas. At least groups like the Locust had the good sense to keep their remixes as hidden tracks. J.H.

Skapocalypse (1995)

There was a brief, exciting early window when No Doubt broke beyond the Orange Curtain and out of the punk-populated Southern California climes, and young Gwen Stefani enchanted us with her sass ‘n’ abs, her charm so incandescent that she made track pants seem like a cool sartorial choice. The world, and even her in-band boyfriend, had not taken her seriously, but now look at her — she was all up in our MTV. It made her easy to root for. But then the exaltation turned to omnipresence, and soon you couldn’t leave the house without getting caught in No Doubt’s spiderweb.

Though pop-punk had a couple of enormous antecedents paving the way — Dookie and the Offspring’s still-inexplicable breakthrough — Tragic Kingdom was the skapocalypse, the Nevermind moment for every awful punky reggae act who wore ties and had a horn section. It unleashed a deluge of also-rans, lesser thans, and Less Than Jakes, yet none of them had anything like charm of No Doubt. Ska bands that had been forever lurking in the shadows — we see you, Mighty Mighty Bosstones — landed major-label deals and could now skank in the light. Sure, we got the roots-radical Rancid out of the deal, but the whole big bang begat a skasmos of blissfully mediocre bands, with their own varying set of matching outfits, wacky concepts, trombone solos, and clunky puns: Reel Big Fish, Goldfinger, Sublime (yeah, bro, even them), Dance Hall Crashers, the Slackers, Mephiskapheles (satanic ska!), Save Ferris, Voodoo Glow Skulls, the Aquabats, and even future one-hit wonders Smashmouth. They came, they saw, they skanked — and thankfully, 1996 is now long behind us. J.H.

Suge Knight’s deadly promotional stunt (1995)

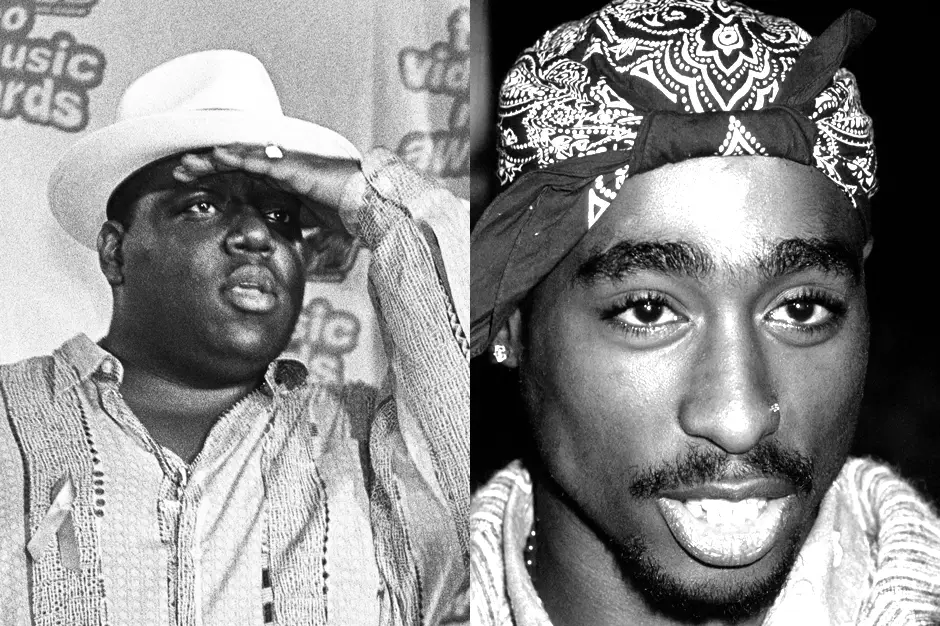

Known for his lunkheaded wannabe-capo antics, Death Row Records figurehead Marion “Suge” Knight decided that recklessly escalating the “East Coast/West Coast” rap feud at the Manhattan-hosted ’95 Source Awards would make for a clever publicity stunt. So, when Los Angeles-based Death Row won for “Soundtrack of the Year” (the Tupac-starring Above the Rim), Suge launched a direct attack on Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, head of New York-based Bad Boy. Making an announcement to “any artists out there [who] want to be an artist [and] want to stay a star,” he invited said artists to “come to Death Row.” Then he made a particularly provocative reference to a certain “producer trying to be all in the videos…dancing.”

Death Row star Snoop Doggy Dog was later booed by the crowd as he received his “Video of the Year” award (for “Murder Was the Case”). Later, Puffy told the audience, “All this East and West got to stop.” Don’t give him too much credit as a peacemaker, though. Before the Bad Boy medley performance earlier that night, Puff declared he would “live and die in the East.” Within 18 months, Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. were both killed for reasons believed to be connected to the feud. B.S.

Women in Rock scam (1995-1999)

There’s a natural temptation to look back on the ’90s as a slightly utopian time for women in rock: There was the proliferation of riot grrrl, of course, and an increasing openness to women-led music (rock or otherwise) in the industry’s conception of “alternative”: Flip on a few episodes of 120 Minutes on VH-1 Classic today and it’s a veritable cornucopia of musicians like the Breeders’ Deal sisters and Josephine Wiggs, Belly’s Tanya Donelly, Veruca Salt’s Louise Post and Nina Gordon, Liz Phair, Juliana Hatfield, PJ Harvey, Tori Amos, L7, the list goes on. But there was a little-known drawback to the bloom of attention that rock women received in the ’90s, and it wasn’t just the magazine world’s invention of the “Women in Rock” special issue (ugh), omnipresent after millions downed Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill. When Lilith Fair emerged in 1997 with a diverse lineup of women meant to further publicize/empower acts who might have gone unnoticed a decade earlier, the unfortunate, ensuing result was corporate marginalization.

Luscious Jackson’s Jill Cunniff discussed the issue with SPIN last year. “It was ironic: Lilith Fair had created all these radio stations that were female-centric, and before that, we’d been on alternative rock stations with, like, No Doubt and Hole and Garbage. Those were the female artists on alternative [radio]. After Lilith, there were all these stations created for women’s music, and the alternative stations cleared out the women. So, by the time our last album came out, they couldn’t get the song on the radio, except on all these feminine stations.” Ever wonder why alternative rock radio was overrun by tepid guitar dudes like Third Eye Blind? Here’s one answer. J.E.S

Is that your chick? Women as collateral damage of rap feuds (1996)

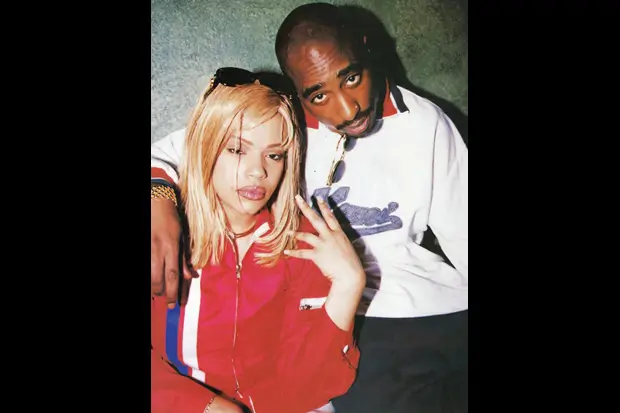

Ever more lascivious versions of the “I screwed your chick” trope are rampant in rap music today, but the over-the-top obsession can be traced back to the most legendary rap beef of the 1990s. The ire between Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. was exacerbated when Pac intimated, on the 1996 track “Hit ‘Em Up,” that he had slept with Biggie’s estranged spouse, Faith Evans: “You claim to be a player, but I fucked your wife,” he rapped, among other things. According to Evans’ 2008 memoir Keep the Faith, Pac actually threatened her — tried to buy her, really — as a way to get back at Big. Three months later, Pac was dead, but even Big believed the affair, rapping “If Faye had kids, she’d probably have two ‘Pacs / Get it?” on “Brooklyn’s Finest.” After Biggie was killed in 1997, the seed for the later Nas/Jay-Z beef was planted, which spilled over into the 2000s with the most devastating dis track in history, Nas’ “Ether.”

But the beef between Esco and Jay-Z went deeper than rap: namely, straight to Ms. Carmen Bryan, mother of Nas’ first daughter, Destiny. In her own extremely salacious tell-all It’s No Secret, Bryan detailed the dramatic love triangle between her, Nas, and Jay over the course of a few hundred pages. Jay Z, though, broke it down to two lines: On the “Ether” reply “Supa Ugly,” he rapped, “Me and tha boy A.I. got more in common than just ballin’ and rhymin’ / Get it? / More in Carmen.” Accepting that he was the first-ever rapper to be ethered, Jay simply hit back where it hurt most, accusing Bryan of sleeping with him and NBA star Allen Iverson, referencing Biggie’s own wifey-as-collateral-damage line. There are two morals to this story: 1) It’s not a game, people; and 2) Women need to take over the rap industry and straighten out all these shamefully shady dudes. J.E.S.

The swing-revival scourge (1996)

Squirrel Nut Zippers’ swing-influenced 1996 hit was called “Hell,” a too-obvious-but-still-accurate description of this wretched genre-glitch that beset America in the late 1990s, taking the twisted and cheeky cocktail-tiki-kitsch underground and reducing it to another excuse for straight white chuckleheads to play dress-up in Mommy and Daddy’s clothes, get drunk, and dance like the Nazis never invaded Poland. We should have known from the beginning that any trend sparked by a Jon Favreau movie and a Gap commercial hawking khakis was going to be a nightmare, but there you have it: penny-loafered models jitterbugging to the Brian Setzer Orchestra’s “Jump Jive an’ Wail” in a 30-second 1998 spot, which somehow led to Big Bad Voodoo Daddy playing during halftime of the 1999 Super Bowl. You know who played at halftime of this year’s Super Bowl, right? Beyoncé! Which says less about the popularity of Big Bad Voodoo Daddy’s Americana Deluxe (blech) and more about the dismal year that was 1999. And let’s not linger on the case of the Cherry Poppin’ Daddies, a band of hippie-funk opportunists from Eugene, Oregon, who performed with burlesque dancers and giant ejaculating phalluses before becoming undeservedly famous for appropriating “race music” and cheekily namechecking history-altering race riots. If all this still doesn’t sound like a grotesque wart on American pop culture’s mug, consider: Cherry Poppin’ Daddies have a new album dropping this month, and it’s called White Teeth, Black Thoughts. In addition to swing music, they will also incorporate zydeco. So… J.E.S.

Boobie bozos: The Bloodhound Gang (1996)

With these suburban Philly jokers, there is at once so little to understand — there will always be someone to laugh at a diarrhea joke — yet, in retrospect, they seem totally incomprehensible. Bloodhound Gang only could’ve been huge in the free-for-all ’90s, and they did so by being inscrutably dumb and totally cunning, hedging their bets by dabbling in every gnarly trend at once: whiteboy rap, white stoner reggae, electronica novelty, rap-metal, rock band-with-DJ, et al. Essentially, fart jokes set to music. As frontman Jimmy Pop bragged, “Like a hemorrhoidal itch, yo, you can’t ignore me.”

Hot on the heels of Nirvana, they were Geffen’s biggest outta-nowhere success, but even the label drew the line at the band’s “Yellow Fever,” pulling it from their 1996 album One Fierce Beer Coaster. The song was so loaded with racist rhymes about Asian women (“Chinky chinky bang bang”) that it makes Yeezus‘ “sweet ‘n’ sour” lines seem like a tender passage from Joy of Sex. “The Ballad of Chasey Lain”, a single from 1999’s Hooray for Boobies, is written from the point of view of an obsessive stan demanding to eat the porn actress’ ass. The uncensored video for “Uhn Tiss” features Jimmy Pop getting a blowjob from a dog through a glory hole, while the video for the group’s biggest hit, “The Bad Touch,” is a horror show of stupid ideas: Dressed as monkeys, the band members’ spy some primate freaking on a TV show, and thus inspired, they rampage through the streets of Paris looking for women to take prisoner, drugging and abducting a clan of model chicks, who get thrown into a cage, along with a gay Parisian couple, some chefs, and a dwarf dressed as a mime. “Put your hands down my pants and I bet you’ll feel nuts,” intones Jimmy Pop, making clear that no entendre is beneath him. The band humps each other in front of the Eiffel Tower, the models are subjected to pawing before a morbidly embarrassing dance sequence, and the mime meets his end via the hood of a Le Car.

Too bad we cannot say the same of Bloodhound Gang’s career. Just recently, bassist “Evil” Jared Hasselhoff stuffed a Russian flag down his pants during a performance in the Ukraine, and Russian authorities banned the group from performing. Later, band members were attacked by Russian Cossacks in an airport lounge. Just stop, already. J.H.

Electro-Crash: Spawn: The Album (1997)

Lucky for us, the rock-meets-EDM future that everyone predicted in 1997 turned out (almost 15 years later) to be Skrillex, and not the shotgun robo-marriage of Spawn: The Album. A sequel to the rappers-meets-rockers clusterfunk of 1993’s Judgment Night soundtrack, practically every single thing on this experiment is an unmitigated disaster, 14 collaborations that used the then-popular record-label dictum “electronica will yield the next Nirvana” as a reason to book loads of studio time. A wheedle-wheedling Kirk Hammett joined Orbital to make the Tron version of acid-jazz; Moby and Butthole Surfers crafted a lethargic post-“Pepper” dirge but forgot to include the pop hook; Mansun and 808 State peddled the Madchester resurgence that no one wanted; Henry Rollins spat alt-bro slam poetry over Goldie’s frantic breaks; and Soul Coughing’s M. Doughty spat alt-bro slam poetry over Roni Size’s less frantic breaks. And has there ever been a more ’97 phrase than “Incubus vs. DJ Greyboy”? Well, try this: As hard as it may be to believe, the album’s saving grace may have been the team-up between Filter and Crystal Method, only because it sounded like God Lives Underwater. C.W.

MCG as visual genius of artifice (1997)

Joseph McGinty Nichol, better known as McG, arrived in the mid ’90s, when a grunge hangover had alternative-radio listeners craving jaunty hooks, bright imagery, and cutesy lead singers. He sneaked through by way of Newport Beach, California high school buddy Mark McGrath, producing Sugar Ray’s first album, Lemonade & Brownies, and co-writing their second album’s mega-hit, “Fly.” From there, he moved on to videos, directing candy-colored, self-consciously flashy, image-defining clips for Sugar Ray, Smashmouth, the Offspring, and Korn, mindlessly transferring the celebratory hip-hop excess of Hype Williams to cocky, empty douche-rock. Lazy color filters on everything gave the illusion of cohesion, while wide-angle lenses and skewed angles gave lunkheaded teens the idea that this was edgy, fresh stuff because it looked like a Gatorade commercial. McG ended the decade by making the Charlie’s Angels movie, which set new standards for colorful vapidity. B.S.

The worst guitar solo of the decade: Creed’s “With arms wide open” (1998)

Generally speaking, the ’90s brought with it a reaction against the fleet-fingered masturbatory antics of ’80s pop-metal guitar show-offs. Sometimes the resultant anti-solos took the form of a simple restatement of a song’s main melody. (A favorite trick of Kurt Cobain’s.) Other players, like Tom Morello or the Edge of U2’s Achtung Baby era, radically refashioned the sound of solos. Insofar as they actually took the time to think about the function and purpose of what they were doing, those players were the exception. From Mike McCready’s relentless blues basics in Pearl Jam at the beginning of the decade to Carlos Santana’s Supernatural regurgitations at the end, the ’90s boasted plenty of the self-involved preening that the anti-solo was supposed to displace. And no solo was more pompously hollow than Creed guitarist Mark Tremonti’s whiff on “With Arms Wide Open”: the aural equivalent of a decadent royal shining his scepter. It’s not particularly flashy, nor is it particularly long, but the unimaginative bombast jammed into the lead’s few bars is truly staggering —the six-string equivalent of Scott Stapp’s messianic, moronic ramanah. D.M.

Nookie Monsters: Backstage Sluts DVDs (1998)

In which nü-metal’s leading penis-people — mugging-for-the-camera bozos including Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst, Korn’s Jonathan Davis, Papa Roach, Insane Clown Posse, and more — take their music’s wounded macho nihilism and pair it with lo-fi digital-porno culture, jack-hammering away in an attempt to boost their desperate limp-dick egos. Of course, all of this was presented as society-bucking, rock-star hedonism instead of the pathetic sexist nonsense that it was. This was perhaps the saddest, most oppressive example of trashy wish-fulfillment ever committed to film — witness the aggro chuckleheads in Papa Roach hurling lunchmeat at a pitiful, wayward bimbo. A second volume (subtitled “No Ass, No Pass”) even featured El Duce of the Mentors, which pretty much tells you all you need to know about just how low this time capsule of white piggy-man nonsense was willing to stoop. B.S.

Three-dollar rip-off, y’all: third-tier Nü-Metal (1998-99)

It took until the new millennium for the record industry to accept its stompin’ whompin’ fate — they had to offer legally binding contracts to bands with names like Ill Niño and Unloco. But in the short, post-Bizkit haze of the ’90s tail-end, some early birds caught the flappingly loose bass string that looked like a funky worm. California “G-punk” Beastie-core buffoons (hed) p.e. dropped a record on hip-hop label Jive, who unsurprisingly couldn’t figure out how to market their monochromatic riffs and adenoidal whines. The Ozzfest ’99 second stage buzzed with the generic chug of Kansas Korn-balls Shuvel, who sounded like Rage Against the Machine if they’d never heard Minor Threat. Fellow ’99 second-stagers Apartment 26 came from the death rattle of that “lets put jungle breaks and porno moans on everything” era, with big hooks that looked forward to P.O.D. — a shame for the band that their 2000 debut came out the same year as Linkin Park’s. Sweden’s Drain STH probably would’ve been an Alice in Chains/Babes in Toyland-style grunge band if they hadn’t had Backstreet Boys producer Herbie Crichlow yelling, “Throw your hands in the air / Wave ’em around like you just don’t care” as a chorus. And California also-rans Kilgore brought Pantera’s grooves and bark into the hip-hop age, but were sidelined by Jay Berndt’s lead vocals, which sounded like James Hetfield doing a bad Cartman impression. C.W.