“This is Chi, right?” blurts Kanye West, arguably the world’s most famous rapper, after shouting out three underground Chicago artists — L.E.P. Bogus Boys, Chief Keef, and King Louie — whose exploding stardom might be helping him more than the other way around. That line, on West’s recent remix of Keef’s “I Don’t Like” (featuring guest MCs Pusha T, Jadakiss, and Big Sean) signaled the increasing spotlight on Chicago rap, a scene that’s currently burning at its brightest since Do or Die, Crucial Conflict, and Twista first achieved national success in 1996 and ’97. The nation’s third-largest city, Chicago gave birth to house music yet has always been underrepresented on hip-hop’s national stage. The city’s current rap resurgence, however, seems to be occurring at all levels, as a younger generation collides with new technology and cheaper distribution. A bustling YouTube culture has magnified awareness of homegrown artists, particularly the East Side street-rap network known as the “drill scene,” marked by booming, slow-rolling, Lex Luger-esque beats and rappers like the 16-year-old Keef, King Louie, Lil Durk, and Lil Reese.

Since the success of the Windy City’s own Kanye West, Chicago rappers have had moments of notoriety and commercial success, but, like West, artists often left the city to “make it.” West helped promote Rhymefest, GLC, and veterans like Common and Twista, but the city couldn’t coalesce around his sound, since New York already had claimed it on Jay-Z’s The Blueprint. Lupe Fiasco’s attempts to build a following were slowed by his crossover appeals to nonrap audiences. The “hipster rap” nexus, with acts like the Cool Kids and Kid Sister, grew out of parties and streetwear boutiques to become a media phenomenon. But the local scene flopped commercially, while artists like Pittsburgh’s Wiz Khalifa ended up monetizing that style nationally.

The first sign that things were shifting was the breakthrough of the long-bubbling L.E.P. Bogus Boys in late 2010. The Point Break-inspired visuals of their “Goin’ in 4 the Kill” video attained a low level of YouTube virality, reaching major publications and focusing newfound attention on the city. West’s former manager John Monopoly co-founded the independent record label Lawless Inc., which soon signed East Side mixtape phenom King Louie as a flagship artist. No I.D., the Chicago producer behind Common’s 1994 classic Resurrection, and West’s early mentor, became an executive vice president at Def Jam and promptly picked up local lyrical auteur Mikkey Halsted. Labels started pursuing L.E.P., YP (who since has signed with Universal Republic), Rockie Fresh (a crossover candidate who has collaborated with Fall Out Boy’s Patrick Stump and Good Charlotte), and the hip-hop band Kids These Days (who recently performed on Conan and whose next album is being produced by Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy).

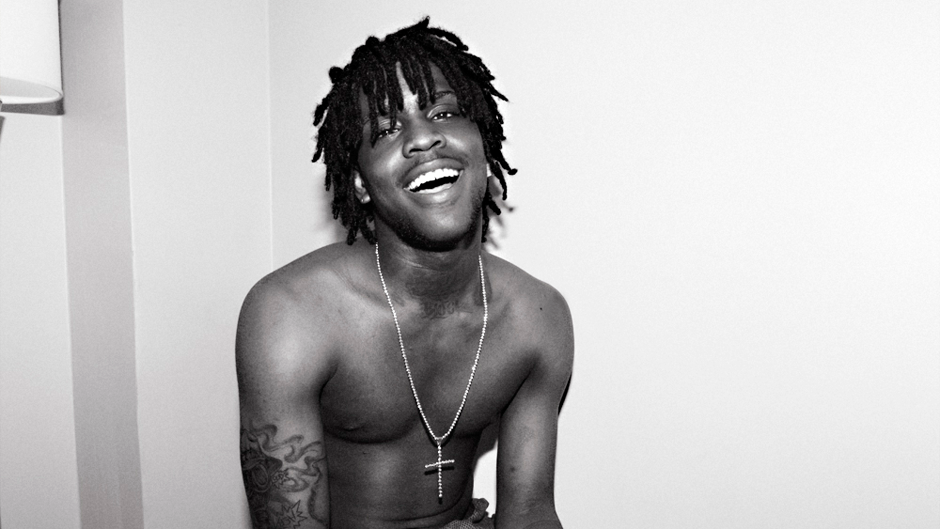

Then, this year, Chief Keef suddenly shot up out of obscurity. Emerging rap stars like Meek Mill, Danny Brown, and A$AP Rocky enthusiastically co-signed him, culminating in the “I Don’t Like” remix, a label deal with Interscope, and a publishing deal with Dr. Dre. In April, Keef associates Lil Durk and Lil Reese joined the Def Jam fold. Local radio stations Power 92 and WGCI began competing to bring attention to local acts. But what gave all of these elements the most forward momentum was the pressure that had been building up in recent years as large numbers of Chicago’s poorest communities had begun to come online for the first time.

At the forefront of this momentum was the “drill scene,” a grassroots movement that had incubated in a closed, interlocking system: on the streets and through social media, in a network of clubs and parties, and amongst high schools. It was this movement that finally exploded and drew the nation’s eye to a city that had a plethora of radically different sounds developing in isolation.

The sound of Chicago’s hip-hop scene is the sound of extreme segregation. Chicago’s white residents once showered Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with rocks as he marched through the South Side neighborhood of Bridgeport, and the city remains the most racially divided in the nation. When Frankie Knuckles, the godfather of Chicago house music, moved to the city from New York in the 1970s, he was shocked by the difference. When he first began DJ’ing to segregated crowds, he initially thought it was a problem with his parties, rather than a preexisting mindset: “The white kids didn’t party with the black kids,” he told dance-music historians Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton. Ride the Red Line train south past Roosevelt and watch white commuters exit en masse. Or ask around about former Chicago Police Department detective Jon Burge, who allegedly ran a squad that freely tortured black suspects and terrorized the South Side throughout the 1970s and ’80s, with minimal legal repercussions (Burge was eventually fired in 1993). Perhaps most visibly, look at the remains of Chicago’s segregated project towers, monuments to what had been, at one time, the nation’s largest public housing system, and which were razed throughout the 2000s. As families were uprooted, the gangs that the older generation credit with policing communities became fractured. Today, the perception is that street violence in Chicago has become more chaotic and that there are innocent victims and collateral damage. (According to the New York Times, homicides are up by 38 percent from just a year ago.) Much of what has made Keef’s controversial music resonate so widely throughout the city is that his young age and seemingly reckless lyrics — dense with references to local sets, cliques, neighborhoods, and gangs — appear to epitomize this very sense of having lost control of the younger generation.