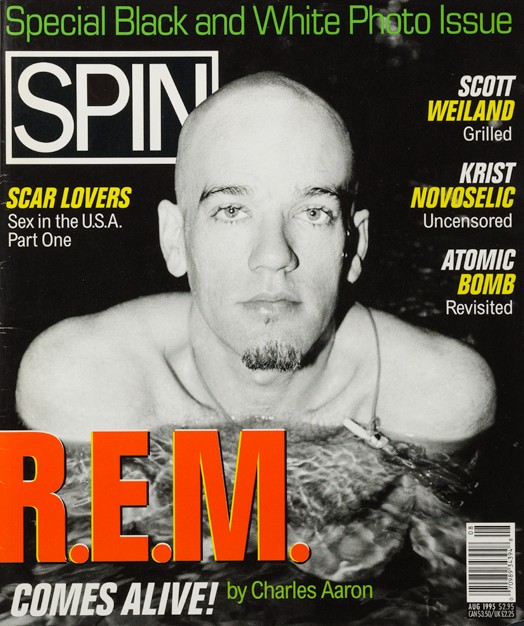

This article originally appeared in the August 1995 issue of SPIN.

In the ruins of ancient Rome, tourists peer through the locked gates of the Colosseum as tomcats scurry and vendors hawk sidewalk sketches of Judy Garland and Shannen Doherty. An Italian boy whistles from a passing bus and points out the obscenity he's scrawled on a dusty window.

To the north, near Villa Borghese (Rome's Central Park), a handful of forlorn girls linger in the drizzle for a glimpse of celebrity outside the Hotel Excelsior, where Kurt Cobain botched a suicide attempt over a year ago.

To the south, a clump of teenage boys and girls huddle under a cloud of cigarette smoke beside a bootleg T-shirt stand in the parking lot of an intimidatingly bland sports arena. Across the numbing hum of the highway, a planned residential community waits for daylight to expire and the kids to come to bed.

But first, there's some rock'n'roll business to be conducted. So the boys and girls are huddled in the Universal Exposition of Rome (or EUR, pronounced sort of like "Eeyore" Winnie-the-Pooh), a mini-city outside the city originally intended to host the 1942 World Expo until construction was halted by World War II. Completed before the 1960 Olympics, this conglomeration of housing and stadiums, charitably described in travel guides as "sterile" and "ugly," is now home to a sizable chunk of Rome's upper middle class. And this gloomy February evening, its Palazzo hello Sport, or "Palaeur," is host to the first-ever local concert by R.E.M., genial guidance counselors of alternative rock and resident hipster uncles of pop music's upper middle class.

With the college-radio days of the early '80s a trace memory, and their albums now guaranteed million-sellers, the members of R.E.M. have devoted much of the '90s to figuring out how to finesse the bigness of success without grossing themselves out, emotionally or musically. After 1989's Green tour, the band retreated, not playing live to support the follow-up albums, 1991's Out of Time and 1992's Automatic for the People. They did virtually no press, pursuing other interests—singer Michael Stipe's film production companies, C-00 and Single Cell Pictures; drummer Bill Berry's gentleman farming; bassist Mike Mills's golf game; guitarist Peter Buck's divorce, remarriage, and parenthood. But with the release of Monster, and for R.E.M.'s first tour in five years, the band has apparently decided to reenvision itself as the R.E.M. Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings, reentering arenas and entertaining enough press requests to run down Drew Barrymore's batteries.

But from where I'm loitering, it's a pity that anybody has to pay to hear the neatly situated glam-pop, garage punk, and trembly ballads from Monster in this gray, echoing dome, which is better suited for team gymnastics or the 400-meter freestyle. A fuzzed-up comment on arena-rock machismo, that album doesn't project so well in an actual arena. All the nuance and humor and coy sexiness fades into forced posturing. The tremolo loses its ironic twinge, and your focus wanders to Mills's hideously unironic, spangled cowboy costume. "Whenever we do 'hard' rock, or whatever this album is, it's always going to be just a little bit off," concedes Buck.

Admittedly, I'm in no position to be objective, after enduring a six-month, can't-get-there-from-here interview runaround: lame video shoot for "Bang and Blame" (where I dispiritedly watched Stipe, MTV journalist Tabitha Soren, and grunge plaything Stephen Dorff shoot squirt guns into each other's mouths); New York hotel conference-room how-don't-you-do; Italian hotel breakfast mess (don't ask).

Of course, R.E.M. doesn't owe the press anything, and I appreciate the change to fly over and check out St. Peter's Basilica, but if setting up an interview is going to be such a federal case, why is Warner Bros., the group's record company, even bothering? Is somebody worried that if R.E.M. doesn't bleed its publicity stone dry album sales will lag? (The triple-platinum Monster rests at No. 72 on the Billboard charts).

Is the band itself worried or feeling obligated? "These are all things we could say no to," says Mills. "But there's no point in being that difficult." The whole enterprise has the aroma of corporate responsibility, which is fine, if you cop to it. But R.E.M. also insists on pushing its integrity-dignity party line. Seems like every third person associated with the tour has to testify to what normal joes the guys still are compared to most big-shot rock stars.

https://youtu.be/jWkMhCLkVOg

So why are they putting on a big-shot rock tour? The stock answer is that the band members felt detached from each other (Buck now lives in Seattle) and longed for the closeness they once shared as a touring band. But taking a gander at the six equipment trucks and nine busses and 47-person road crew crowding the back of the lot at the Palaeur, not to mention the wives and kids and chefs along for the ride, I wonder if maybe the band wouldn't have been better off just getting together for a summer barbecue.

Wasn't it Stipe, 35, who said after the Green tour that it took him a year to feel like a real person again? Mills, 36, strides around like a burnt-out Burrito Brother, shades on, guard up. Berry, 36, who first encouraged the tour, has dropped out of sight, suffering from fatigue. (A week later, Berry would collapse onstage in Lausanne, Switzerland, undergoing successful surgery for a double aneurysm, thus ending the European tour.)

And sure, Buck has always wanted to live his own version of one of those crinkled paperback rock bios he read as a college dropout working at used record stores in Atlanta and Athens, Georgia. But with two kids now in two (year-old twin girls, Zoe and Zelda), he sounds more like a dad caught in the headlights.

"I used to think I worked hard a couple of years ago, but that was nothing," says the 38-year-old guitarist, sitting in a wicker chair in a covered Palaeur locker room. The twins' purple trunks, with their names stenciled on the sides, are rolled up against the far wall. "My day is filled from the second I get up to the second I go to sleep. There are pleasure things I'd like to do, like go sightseeing, but there's hardly 20 minutes when I can take a nap. It's not like our nanny can do everything….But one of the things we have to remember is that this is our life, this is what we do. This is how I choose to live my life and I'm happy about it."

[caption id="attachment_id_344553"]  Chris Carroll/Corbis via Getty Images[/caption]

Chris Carroll/Corbis via Getty Images[/caption]

On the Palaeur's concrete concourse, crew members with panicked eyes and upbeat expressions whisper into the walkie-talkies. I feel like I'm waiting for a blind date to a prom held in a bomb shelter.

Finally, Stipe turns up, publicist and assistant alongside, looking surprisingly spry. He's wearing a knit ski cap with a question-mark logo pulled tight over his bald head, leather jacket over a floppy T-shirt, big pocket key chain clanking against black jeans, and stylishly clunky motorcycle boots. Very Warhol superstar, in a neatly pressed, approachable way. He extends a hand, fingernails painted blue and chipped, grins sheepishly and gamely remembers my name.

"You know," I venture after we've retired to the locker room, "I've begun to think that R.E.M. stands for 'Really Elusive Michael.' I didn't expect such a hit-and-miss interview ordeal."

"When was the last time we talked?" Stipe sits up, elbows on knees. "In New York, during the Grammys?"

I tell him it was at the MTV Video Music Awards.

"Well, you shouldn't take it personally."

I don't, really, and I guess I should thank the band for blowing me off in New York since I scammed a free trip to Italy out of it.

"We weren't blowing you off," Stipe says, slightly offended, his good cheer visibly dissipating.

"I know that, but for the pst six months I've kind of felt like I was standing in a stag line with Old Man Schwump, like on The Andy Griffith Show."

"I never watched that show."

Awkward silence. I wonder again if this isn't kind of an overwhelming, counterproductive process.

https://youtu.be/4cdZQ41rGAg

"In spite of myself, in spite of my history," he begins, taking a deep breath, "I try to make these things into conversations, you know, which depends on who I'm talking to. But basically, everybody asks the same four questions anyway, particularly in Europe."

"Well, after reading all your interviews, it seemed like you gave the same four answers no matter what questions anybody asked."

"I don't know what you mean." He pauses. "I'm confused."

"Anyway, when we talked last year, you said that you were sacred of repeating the Green tour experience. Have your fears been justified at all?"

"Oh, not really. I just eventually got tired of using that line." He laughs, breaking the tension. "Now I'm loving touring. The travel has been grueling, and we're only seven weeks into it, but we're taking as many precautions as possible so we don't fall apart again or whatever….At the end of the last tour, I felt like somebody dumped my body out at the bottom of my driveway at home and I couldn't move. Right now, it's still kind of fresh and exciting."

I suggest that he finally seems to have the faith of his own pretensions, that he's no longer going out of his way to seem so self-effacing.

"No, I still think I'm pretty self-effacing." Deadpan pause. Then he grins. "You know, I like this idea of doing an interview about doing interviews, though. That's kind of wild."

"I thought about bringing in all the clips, spreading them out on the table and asking, 'So why did you say all this silly shit?'"

"Yeah, it's like I'm being reflected in the mirror which is reflecting the camera which is taking a photograph of the mirror." HIs voice trails off as he reconsidered the question of his so-called pretensions. "Well, of course, there's a point at which it gets ridiculous, the whole self-effacing act, and truthfully, believe me, I do and don't take all this very seriously. But I can't possibly take it seriously all the time or I'd go batty. Then again, I've never thought I was as pretentious as everybody else thought. But maybe by saying that I'm being pretentious. I have no idea anymore."

[caption id="attachment_id_344557"]  Chris Carroll/Corbis via Getty Images[/caption]

Chris Carroll/Corbis via Getty Images[/caption]

Maybe people think you're pretentious, I offer, because of the games you play in the press with your sexual preference. It sometimes comes off like a put-on to get attention.

"Well, just in defense of myself, and not in a defensive way at all, I've aways fucked around with gender. And I've never played the game of arriving at big media events with supermodels to try and prove that I fuck women. If I suck dick or suck pussy of if I alternate between the two, it's my business and nobody else's. People can make whatever assumptions they want, and they have. I think a lot of people just assume that I'm queer and that's fine. I've never been ashamed of anything and I've never denied anything."

"It's interesting that you've talked a lot about Patti Smith being your main inspiration for getting into rock'n'roll. I can't think of any other male rock star who has ever said that about a female musician."

"Patti Smith was a woman, but she was also in that gray area that I feel like I embody as a public figure, the neither-nor. I've always responded to that in a big way. She was not a woman as women were generally defined in 1975 in the United States, she was something wholly other, and not just because she looked androgynous. And I kind of made myself, as much as I could, without it being some kind of theft, into my version of her."

"You know, I spoke to her for the first time on the telephone recently. I called her from this anarchist book store in San Sebastian, Spain, and it was really great just to talk, because I've, in the past, exalted her to some kind of heroic, unreasonable level. That first album [Horses] was the most important thing in the world. It was always like, 'God, she's sending some weird, secret message to me.'"

I mention that what struck me about Horses was the way Patti Smith sang about religion. She was so turned on and disgusted by it.

https://youtu.be/j4iuG7StmPc

Stipe hesitates and sits back. "I never really got the religious thing. I mean, it's there, 'Jesus died for somebody's sins, but not mine.' But I didn't grow up in a strict religious situation, so…"

"But wasn't one of your grandparents a minister?"

"My grandfather on my father's side was a Southern Methodist preacher. But it wasn't like a Fundamentalist, born-again Baptist thing. The Methodist church doesn't try to dictate every single aspect of your life."

"Yeah, I was raised Southern Baptist and I resented the Methodist kids because they got to wear turtlenecks to Sunday service and sing cool songs."

"Really? Oh, Jesus." He scoots forward, laughing. "Well, Methodism was started by John Wesley, who was, in his way, a really radical guy who believed in a lot of individual responsibility. It's not the kind of religion that's right around your throat. Actually, I was named after him, John Michael Stipe."

Since R.E.M. has always been thought of as a spiritual band in some undefined way, do you think your grandfather's preaching had any impact on your that surfaces in the band?

"Possibly. My grandfather wasn't generally a pulpit-pounder, although, I don remember him doing that from time to time and it making a big impression on me. The excitement from that, for a kid, can be really overpowering. I don't know what the right word is, it was more than just a 'kick' or a 'thrill.' It was just like, 'Wow!' It's such great theater and can be so beautiful. I guess I wanted to be part of that somehow, maybe not the religion, but just that feeling that my grandfather was giving off."

* * *

"You've got to remember one thing about R.E.M.," my friend Stephen advised me in an eerily Stipean mimic. "This is bigger than you…and you are not me." Of course, he was simply adding to the "Losing My Religion" joke book, but he was also making a crucial point. For many people—likely including Stipe's close friend Kurt Cobain—R.E.M. was never really about the music. I was an iconic, almost religious presence, a dues-paying symbol of how to survives as artists amid the exploration of the music business. Good-hearted corporate aesthetes who lived the American bohemian dream—buying in without selling out—and wrote the business prospects for alternative rock that Nirvana capitalized on.

That Automatic for the People was one of the most wittily self-aware and exquisitely mournful albums ever recorded, or that Monster raised the stakes by roughing up the band's entire sound and persona, was secondary to R.E.M.'s rigorously respectable public image. The band members never pushed our buttons with self-serving feuds or drug-rehab journeys. But now everybody "respects" R.E.M. so damn much (e.g., magazines chronicling their importance by printing set lists like sacred texts) that compliments start to sound like backhanded insults, and you forget how fun and smart their music can be.

For instance, when I asked Courtney Love why R.E.M. was so important to her and her late husband, she rambled on about being Buck's neighbor in Seattle, how she gave him a prototype of a guitar Kurt invented for Fender, how she saw the band do "Let Me In" (the song on Monster about Kurt) live in Bodukan and almost cried, and how she gets such a feeling of "well-being" from R.E.M.

"Michael Stipe is the sexiest man in America by a fucking country mile," she crows, "and if he ever decides to breed, I would appreciate being in the top five. In fact, I demand it." Typical Courtney. But also typical R.E.M. fan. Always going on about all the stuff around the music.

Which is bizarre, since my idea of what rock'n'roll should sound like was explicitly shaped by R.E.M. while I was a student in the early '80s at the University of Georgia in Athens. At one point, the band played every three weeks for two dollars at Tyrone's, a run-of-the-mill bar that started a new wave night in 1980-81 because of Pylon's popularity and lucked out as R.E.M. packed the place.

[caption id="attachment_id_344560"]  Chris Carroll/Corbis via Getty Images[/caption]

Chris Carroll/Corbis via Getty Images[/caption]

Instead of thrusting out at you from the stage, R.E.M.'s songs subtly swept you forward. The rhythm section's melodic swirl and Stipe's lulling vocals were immediately intriguing. As a result, everybody danced, but in this introverted, twitchy way I've never really experienced since, except maybe at raves. I was the spectacle of uptight white kids trying to feel good about their bodies, and succeeding.

What Athens brought to rock'n'roll was this non-macho, non-confrontational, communal stance. It was not punk. Nothing sucked and hostility was in bad taste. Lead singers didn't beg you to fuck them or hate them. R.E.M.'s guitar-pop aesthetic was influenced by a scene enamored with European new wave, funk, '70s soul, and glam rock, plus the liberating groove of the New York gay club scene. Compared to most other American rock bands at the time, R.E.M. was practically disco—all bass lines, nifty beats, and superfluous, sensual lyrics. I figured the band was too specific to Athens's subculture for anybody else to get it.

Guess not. Everybody got it, or got something about it (the dance-culture twist straightened out as Buck's guitar playing improved. And R.E.M. became the most beloved band of the '80s, releasing Murmur (the doleful pop-rock debut album that was nothing like its live show) to great acclaim, touring endlessly when few had the nerve, helping create an underground where non existed. And as the years passed, the band remarkably reinvented its sound a number of times, leaving Stipe's vocals the primary signifier, possibly accounting for fans' inability to describe the band's lingering appeal.

R.E.M. has inspired legions of other bands, from goody-goodies such as Live to cut-ups such as Pavement. "When I was 15 years old in Richmond, Virginia, they were a very important part of my life," says Pavement's Bob Nastanovich, "as they were for all the members of our band. [Singer-guitarist Stephen] Malkmus was heavy into them when he went to school in Charlottesville [at the University of Virginia]. I bet [guitarist Scott] Kannberg bought Monster the day it came out and played it ten times. [Drummer Steven] West was even in an R.E.M. soundalike band."

"They were always this uniting force. People who liked Black Flag liked 'em, people who liked the Dead liked 'em. They were the fist band that the frat guys looked at and didn't say, 'Oh, let's beat up some fags.'…It also turned people's attention to the South. People never through about places like Georgia or South Carolina. Then they were taking vacations down to 'R.E.M. country,' just driving around listening to R.E.M. records."

https://youtu.be/ycvJHQUqU1M

"It was a weird fashion thing too, like in my high school, you had large cliques of people who would dress like Michael Stipe, you know, raiding thrift stores and waring really neutral Army khaki stuff….Now, I don't know what's up with those guys. It's almost like a college team trying to play in the NBA."

R.E.M.'s fans have often poked the band when its sincerity shtick got too thick or self-congratulatory. Last year, the Beastie Boys' Adam Yauch, disguised as an enraged sheep farmer, hijacked an MTV video award from Stipe.

"I was just howling," says Buck, "but everybody around us, like Aerosmith, were all tensed up." Usually the digs have taken the form of song parodies, indirectly revealing a deep appreciation for the band's music. Like when the Butthole Surfers, who moved to Athens in the mid-'80s, covered "The One I Love" while burning dollar bills. "I have a bootleg of them doing that," says Buck proudly. "I thought it was great the the Buttholes took the time to learn one of our songs.

Or when the Dead Milkmen came to Athens dressed in long-sleeved white shirts and black vests (á la Buck) and did an obscene version of "Driver 8." "It's cooler than a tribute album," Buck laughs.

One tribute, however, that the band has admittedly never made sense of, and in its own smirky-quirky way may be the most insightful assessment of R.E.M.'s meaning and appeal, is Pavement's "Unseen Power of the Picket Fence" from the No Alternative compilation. "Classic songs with a long history," declares Malkmus on the grinding build-up, and he's so quixotically passionate, his clipped voice listing all the songs on Reckoning so dutifully, right down to "Time After Time (Annelise)"—his least favorite song! Sing it, brother man!—that you actually believe he believes in something (even if it's not R.E.M.).

The inevitable invocation of General Sherman becomes a perverse vision of Stipe et al. as the chosen survivors of southern culture's scorched earth. It's prepostured and touching. And proves that you can love and respect a band and still hear their career as a precious charade.

* * *

In the Spike Jonze-directed video for R.E.M.'s "Crush With Eyeliner," Japanese teenagers lip synch, pose dead-cool, and mug impetuously inside and outside a restaurant-bar, practically smooching the camera, as Michael Stipe purrs in the background, "We all invent ourselves / And you know me." He's getting off on a familiar paradox—watching someone you think you know remake themselves.

"I don't think the idea of slipping in out of different personalities is unique to performers or people who are part of the pop-culture pageant," says Stipe. "Everybody does it every day, no matter what their job or life is like. I love that commercial where this white, geeky guy stands on a corner and everybody who walks by him morphs into a white, geeky-guy version of themselves. It's for TDK or something. All this happens and they sell a product in the meantime. That could be 'Crush With Eyeliner.'"

Ostensibly, "Crush" is about a girl faking it so real that all her dreams come true. But even more, it's about a girl faking it so real that all her dreams come true. But even more, it's about being obsessed with watching that girl, gazing at the dizzying swoosh of youth culture and wondering where you fit in, when you should get out of the way and to what extent you're responsible for what's going on. R.E.M. has never been totally in with the in crowd, and they know that's part of what makes them so sympathetic. They watch, like most of us, and pick up on things over time.

Jonze deletes the band members from the video until the closing frames, when Stipe briefly appears in a crew-neck sweater and white button-down shirt, sitting at a table in the shadows. He's not lurking, just observing. As Buck once said, "Michael's got this great ability…If he doesn't know something, he'll latch on to people and learn from them."

[caption id="attachment_id_344563"]  Huddersfield Examiner Archive/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images[/caption]

Huddersfield Examiner Archive/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images[/caption]

There was a time when R.E.M. wouldn't even appear in its videos, let alone li-synch, which was interpreted as a no-sell-out move. But the band just hadn't learned how to use the medium to its advantage. In retrospect, videos were a godsend for R.E.M., allowing it to regain some measure of mystery and intimacy. And control. The reticent pop artists could hide in the margins, or, when they were ready, show up as carefully considered images.

With the poignantly studied "Losing My Religion" in 1991, and 1993's "Everybody Hurts," Stipe seriously stepped out in front of the camera, playing an almost preachily role in the latter clip, leading a somber group of commuters away from their traffic-jammed lives.

"Michael is probably the best artist Ive worked with in terms of understanding his performance, even though he's so insecure all the time,' says the director Jake Scott. "In 'Everybody Hurts,' he felt exposed and agoraphobic and I think that worked for the video. It's rare that someone has the confidence and awareness to look awkward and quite afraid in front of the camera."

With Peter Care's video for "Man on the Moon," R.E.M. achieved a sense of pop community that was probably the most confidently sublime of its career. Shot in naturalist black-and-white, Stipe strides through a barren stretch of the southwest, a snake slithering around his boot, cowboy hat cocked on his head, like a wide-eyed army brat duded up as James Dean in Giant. He's a figure, not yet tragic or comic, transfixed by the possibilities of America's expansive spaces.

While projections of the comedian Andy Kaufman flash overhead, Stipe reaches a highway, does a quick Elvis wiggle, and hitches a ride on an 18-wheeler driven by Berry. When he gets off at a truck stop (his "St. Peter's"), the other members of the band, as well as patrons of both sexes and various ages, are offhandedly singing the words of the song to each other, like a comforting conversation. It's one of those potentially corny moments that transcends itself and demonstrates the power of pop music to connect people's lives.

https://youtu.be/Kd5M17e7Wek

And that's why the Monster tour, or at least what I saw of it, was so disheartening. R.E.M., after proving it could be an inspiring international pop icon on its own unconventional terms, was now attempting to prove it deserved the status, but on everybody else's conventional terms. While the album makes rock star life seem like an absurdly affecting holiday, the area show clocks in, clocks out, and heads to the hotel bar. I was reminded of something Berry said in New York before the European tour and his near-fatal collapse.

"It really is ironic. Something starts from your soul, and when it becomes a song, right at that moment, it stops and becomes a game. If you want it to be heard, and we do, then you enter the business world. You don't have to make certain decisions, but if you don't, somebody else will make them for you. It's frustrating sometimes. All of a sudden, you're in a room talking to somebody like you, which is fine, but I had to do it at 3:15 on a Sunday afternoon for exactly X number of minutes. Everybody is so regimented. Like, I know on April 24, 1995, exactly where I'm going to be, what time I'm going onstage, an how many people are going to be in the audience."

But on April 24, 1995, Berry wasn't onstage. He was recovering from surgery and trying to get himself back in shape for the rapidly approaching American concert dates. A brutally challenging situation, at best.

So, in mid-May, with the tour set to kick off, I wanted to ask either Berry or one of the other band members if they were having any second thoughts. After a number of unsuccessful tries to get Mike Mills on the phone, a Warner Bros. publicist called me one last time from the Shoreline Amphitheater, an outdoor venue near San Francisco and the site of R.E.M.'s first U.S. show in five years. She said the band had just sound-checked, and Mills didn't feel up to talking. A thunderstorm was looming and the show had to go on "rain or shine" and well, what else could go wrong? I told her I understood.