The morning of April 8, 1994, I was rudely stirred from sleep by a telephone that would not take a hint. I picked it up and slammed it down without answering at least three times, but whoever was on the other end was not deterred. I did not answer the phone before noon. As a callow, immature, hard-drinking twentysomething, this seemed to me reasonable behavior.

I was in a downtown hotel in Seattle, on assignment for SPIN, writing a story about Sub Pop, the Seattle-based record company that had more or less birthed grunge. I was pretending to work there so I could report to the readers of SPIN what it was like to work at a famous independent record label. I took my job seriously, so I'd been out late drinking the night before with a band on the Sub Pop label called Velocity Girl, who were in town to play Sub Pop's Sixth Anniversary party, scheduled for Saturday.

April 8, to the best of my memory, was a Friday.

Eventually I answered the phone. It was Daniel Fidler, one of our editorial assistants.

"Have you heard?" he asked.

I was hung-over. I was always hung-over back then, but still. Even though I couldn't think straight, and my head was buzzing, my heart cannonballed into my stomach. I knew what he was talking about. I knew, without knowing. Reflexively. I knew, but I didn’t want it to be true. So I played dumb.

"Heard what? It's 9:30 in the morning here. I was asleep, like a normal American person."

"Turn on the TV and call me back."

He hung up. I didn't want to turn on the TV and have my fears confirmed. But I turned it on anyway. Same thing, every channel.

"The body of Kurt Cobain was found lying in a room over the garage at his home in…"

"Preliminary reports indicate he committed suicide by shotgun…"

"Crowds of devastated fans have already begun to show up outside the Cobain residence in…"

He'd finally done it. The poor bastard. Not two days earlier, I'd been having dinner with then-Sub Pop publicist and good friend Nils Bernstein. Nils and I were discussing the latest Kurt gossip. He'd escaped rehab in Los Angeles and made his way back up to his house in Seattle, where he'd unplugged all the phones. (It was a very big house, and back then we had what are called landlines, which required cords plugged into the walls in order to make or receive calls. I know, weird.) He was refusing to talk to anyone. We shook our heads and shrugged our shoulders and drank our Brandy Alexanders. Only a month earlier, Kurt had tried to commit suicide in Rome by stuffing a bunch of pills in his mouth and washing them down with champagne. The incident was played off as an accident, but it was no accident. It was just unsuccessful. Had his wife, Courtney Love, not intervened in time, he might have succeeded.

I called Daniel back. He put me on with Craig Marks, the magazine's whip-smart, no-nonsense Executive Editor. Craig told me what to do: go out to the house, interview the fans, call the medical examiner, get more details, talk to the cops, talk to anyone of Kurt's friends I could track down willing to talk. Do my job, in essence. Act like a journalist. In a very macabre sense, SPIN had lucked out. I was their man on the scene, and I was on the scene first. We could be out ahead of the story. This is what reporters are supposed to live for.

Therein lay the problem: I wasn't a reporter. I wasn't a journalist. I had little reportorial training and was not particularly interested in developing the necessary skills. I'd talked my way into a job at SPIN because I knew about music (I was a musician) and I could write (I was a writer). I'd never interviewed a medical examiner or a cop or really anyone I didn’t absolutely have to in order to cobble together a story. Further complicating matters, I was friends with Kurt. We'd known each other a bit before his band had rocketed to fame and fortune, but mostly during that vertiginous ascent, which was a deeply weird trip for anyone even tangentially involved, especially for Kurt.

He had wanted to be successful, but on his terms, and had no way of dealing with the overwhelming demands put on him by his stratospheric and entirely unforeseen—no matter who in retrospect claims otherwise—triumph. Kurt had hoped for a gold record, worked hard to make a gold record, because that would mean he could keep making music and not starve, which was at the time his fondest wish.

"Smells Like Teen Spirit" was not meant to be a hit single. It was meant to set up the second single, "Come As You Are," which everyone thought had real potential as a crossover, mainstream hit. The record company initially shipped only about 45,000 albums to U.S. stores. When Nevermind exploded, he was horrified by the kinds of fans it attracted. All of that is public record, and should you wish, you can read more, at tedious length, in (among many others—it's a cottage industry!) The Big Book of Nirvana Things (Authorized) by Chapster McFeels. Some of the things Kurt, Dave, and Krist told good ol' Chapster were true, but most of it's just an excuse to air grievances that none of them could bring themselves to discuss face to face, back in the day. Much of the carping is petty and dumb, but it's a breezy read and aces in the underrated score-settling subgenre.

It is nonetheless true in spirit, if not in the specifics, that Kurt was not built for the kind of superstardom that overtook him in the wake of Nevermind's world-beating success. If not for Courtney, who looked out for him in every possible way, and who—despite the bouts of volatility that often characterize a relationship between two strong-minded artists—was one of the few people who always had his best interests at heart, he might have self-destructed sooner. The two of them were deeply in love, and while there was an element of codependency to their relationship, it seemed to me that Courtney and their daughter Frances were the only two people on Earth keeping Kurt going towards the end. The band was squabbling over money, as bands will do, and he didn't want to headline the upcoming Lollapalooza but he didn't want to let anyone down, and he was clinically, genetically depressed, refused to take his antidepressant meds (believe me, we tried), and not good at communicating things in any way other than through music.

It was therefore a shock but not a surprise when he committed suicide. Anyone who uses the working title I Hate Myself and Want To Die, even in jest, for his third album, as Kurt famously did, has issues with self-loathing and depression. Those issues were inextricably tied to his appeal, and his death cemented that appeal to those in his audience, and later generations, who responded to his inability to handle modern life.

But that is not all Kurt was, and it wasn't even very often who Kurt was. Most of the time he was a kind, gentle, caring, friendly, open, curious, intelligent, insecure, quiet young man. He could also be a stubborn, mouthy, contrarian prick. But that was rare, and only when he felt cornered, or threatened, or was being protective of his loved ones. That's not who he was to his friends. That's not who he was to me.

After I hung up the phone with Daniel and with Craig, I sat on the couch of my hotel room in a daze. After speaking with Craig, he'd passed me back to Daniel, who had given me a few numbers to call: the police, the medical examiner, etc. I had written them down.

I didn't make any of the calls that Craig had instructed me to make, and I didn't go out to Kurt's house to interview fans. I wandered out of my hotel at around 3 o'clock in the afternoon, and went up to the Sub Pop offices. A sign on the office door read "No cameras. No comment." Everyone inside was in a state of shock, understandably. There wasn't anyone at the label who didn't know Kurt, and many knew him well.

A few minutes later, a teenaged kid walked through the door.

"I don't have any questions, I don't want to take pictures. Is it okay if I just stand here?" he said.

The label owners, Jonathan Poneman and Bruce Pavitt, were both in the office that day, partly because the Sub Pop Sixth Anniversary party was scheduled for the next night, and they had to decide whether or not to go forward with it. Most of the rock journalists in the country would be flying in for the party—or would have been flying in for the party, and now would be flying in to cover Kurt's suicide.

They took the kid out on the terrace below the office, and tried to console him. There's really not much you can do to console someone in that situation. He was "just" a fan. "Just" one of the millions of kids whose heart Kurt had just broken. He stood out on the terrace for a long time, racked with sobs. They let him stay there. We left him alone. It seemed like the right thing to do.

A cake showed up from Danny Goldberg, head of Atlantic Records and formerly founder of Gold Mountain Management, who managed Nirvana. The cake was in celebration of Sub Pop's birthday, and had been decorated with caricatures of Poneman and Pavitt in icing. It was a deeply weird moment. Nils told me to go get some beer and bring it back to the office. He also gave me some of his Xanax, for which he had a prescription.

The only sane response at that moment, it seemed to us, was to numb the pain. The prevailing mood throughout that weekend was shock and awe, tinged at the edges with a deep sorrow that had not yet surfaced. The Sub Pop party (they decided it was too late and too impractical to cancel) turned into a wake instead of a party, which seemed appropriate.

The next day, after the private memorial service for Kurt, a group of us stood smoking outside. I may not have been smoking, myself, but I was smoking-adjacent. No one said anything until Dave Grohl, grinding his dead cigarette under his heel, shook his head and chuckled, "Talk about passive-aggressive." He wasn't trying to be mean or clever. He was trying to deal with his emotions.

Many of us then went back to the house at Courtney's invitation. A lot of people came and went that afternoon, though most of it's a blur. I remember hanging out with Kurt's mother, Wendy, and his younger sister Kim, who at that age bore an uncanny resemblance to her brother. His mom told a story about one time making breakfast and whistling and Kurt sitting at the table just looking at her, asking, "Why are you happy?"

Courtney walked around in a state of semi-lucid grief that manifested mostly in a manic whirl of activity—she gave guided tours of the room above the garage where Kurt had been found (I did not participate), she went out and visited the public memorial for Kurt taking place that same day (or so I was told), she smoked a lot. I can't imagine the weight of sadness and responsibility bearing down on her in that moment.

Things got so chaotic that at one point I was asked to watch Frances Bean, alone, for maybe the longest 30 minutes of my life. You do not put a callow, immature, hard-drinking twentysomething in charge of a small child. I watched her play. She didn't die. Everything seems to have turned out okay, but that's the last time I have had anything to do with children.

I ended up at Nils' house later that night playing records until 4 in the morning. It seemed appropriate. As I said, we were mourning a person, and not a rock star or the abrupt end to a season of promise. That these might turn out to be related, eventually, did not then enter our heads.

At some point, talking it over with Nils and a disembodied version of myself, I decided not to do the story. In truth I'd already decided, but had not admitted to myself that I'd decided. I left town without telling anyone early the next day and hit the road. From a truck stop one evening a few days later, I called Craig to give him an opportunity to yell at me before he fired me. But Craig wasn't in a yelling mood. On Sunday, Daniel Fidler, the guy who called me to tell me that Kurt was dead, had died of an overdose. Whether by accident or in some excess of grief no one was sure. Daniel was one of the sweetest, most sincere and hard-working young men I'd ever had the pleasure of working with. It was inconceivable that he would take any kind of drug, much less heroin. Whenever anyone tries to get me to tell stories about the glory days of ‘90s rock, all I can remember is the death and the loss. There was a lot of both.

I returned to my temporary hometown, Dayton, Ohio (long story), shaken to the core. Having effectively burned my bridges at SPIN, when offered the chance two months later to play in a local band called Guided By Voices (short story), I jumped. It was not a considered decision, and it's one I would come to regret. But it was something to do, at a time when I really needed something to do.

Within two years I had quit the band, broken up with my fiancée, moved away from Dayton, and stopped drinking. All of them good decisions, in retrospect, but it didn't feel that way. It felt, instead, like that phone call from Daniel Fidler announced more than just the death of Kurt. It announced the imminent death of pretty much everything I had until that moment loved.

In a way, I wasn't completely wrong. Nirvana was seen at the time by many as the culmination of the movement of various strands of punk/indie/alternative/whatever into the mainstream of popular culture. What we did not understand at the time was that Nirvana marked the end, not the beginning, of that movement. After Nirvana, post-Kurt, that movement was co-opted and destroyed by an industry that had no idea what to do with it.

This you could probably have seen coming, and, in an unfairly simplistic way, can be reduced to one word: money. As soon as the big record companies decided that hitherto hidden or underground artists might also harbor hidden riches, the game was more or less over. Took a few years of compromise and rejection (by the public, by the companies, by the bands themselves) to understand that easy lesson.

By the time they did, it was too late. A new sensibility gripped the music business, frustrated with the anti-star mentality of its biggest artists; many of those same artists, unused to any attempt to exercise control over the content or presentation of their music, soured on the major label experience and were either dropped and went back to their underground hideouts, or dropped themselves and did the same, having decided that careerism was not a viable path for a musician with artistic pretensions. The music business then moved on to more malleable pop/rock acts and began a decline from which it has never really recovered (aided and abetted by the Internet, but that's a subject outside the scope of this article).

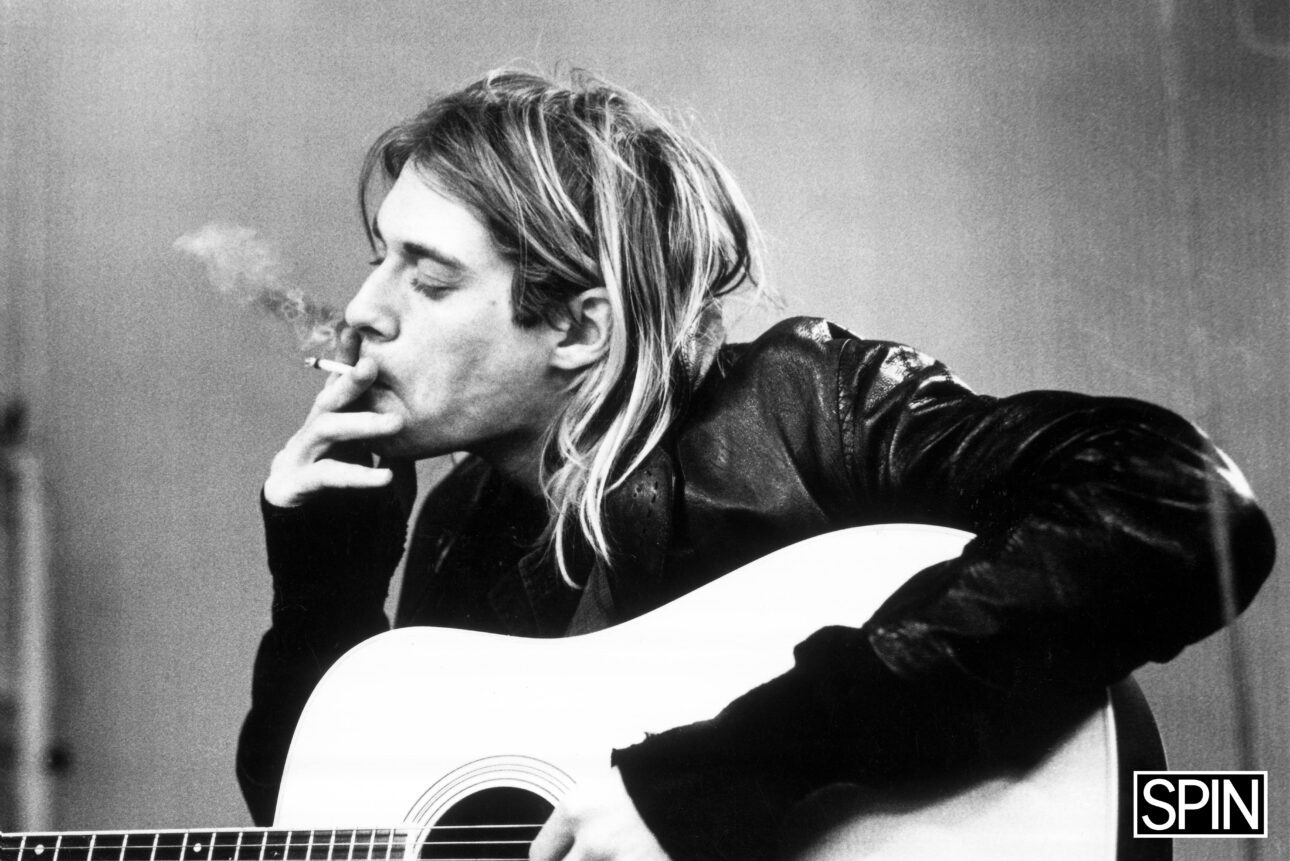

But Nirvana remains—Kurt remains—forever trapped in the amber of his golden-haired youth. The liner notes he wrote inside Incesticide included the statement: "If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different color, or women, please do this one favor for us—leave us the fuck alone! Don't come to our shows and don't buy our records." Well, that didn't happen. It was laudable as a sentiment, as a mission statement, but its ineffectuality could only have made worse Kurt's sense of futility. The people Kurt Cobain did not want to listen to his band's music are now in charge. Everything he was against has risen against us, and it's not his fault. He's regarded now as a Gen X icon, whatever that means, as the voice of that generation, and kids who were not born when he died and have likely never heard a note of his music beyond "Teen Spirit" wear Nirvana T-shirts to signify… what, exactly? A kind of vague anti-establishment attitude that they don't in fact believe in and an embrace of corporatism that the very fact of buying and wearing the dead band’s merch contradicts?

Fine. That's just fine. Thirty years after Kurt's death, feeble gestures like wearing a "Corporate Magazines Still Suck" T-shirt on the cover of Rolling Stone seem charming in their naivety and earnestness. Trying to explain the concept of "selling out" to anyone born post-Kurt is like trying to explain electricity to a cave painter. The danger is that his memory becomes subsumed by nostalgia—a disease for which the only cure is to look ahead, always ahead.

Despite his reputation as a miserabilist, Kurt always hoped and worked for a brighter future. Famous optimist Franz Kafka was once asked about the hopelessness expressed in his work. He replied, "Oh, there is hope, an infinite amount of hope, just not for us." I like to think he and Kurt would have understood each other.

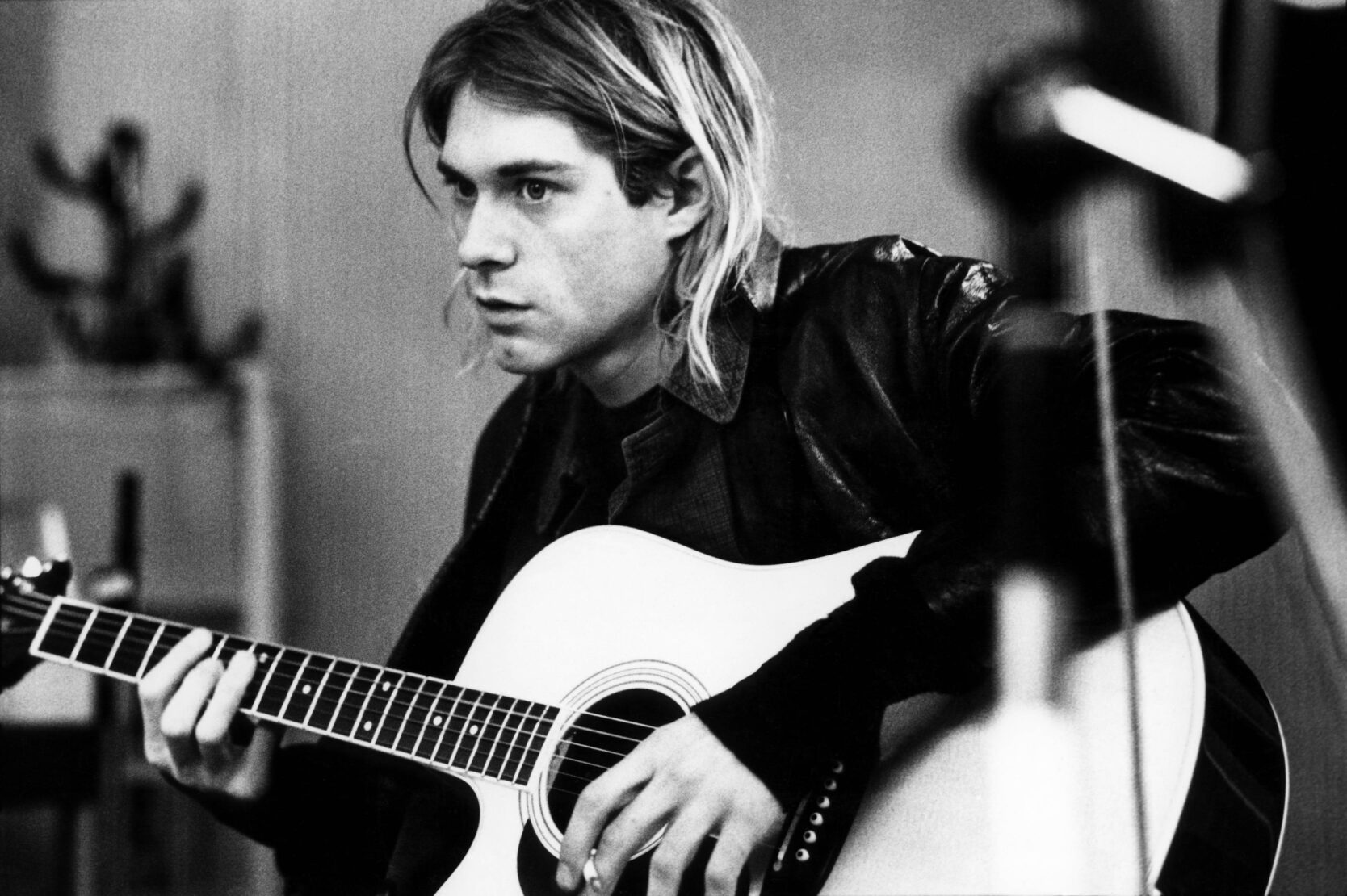

Photo Credit: Koh Hasebe/Shinko Music/Getty Images

Photo Credit: Koh Hasebe/Shinko Music/Getty Images

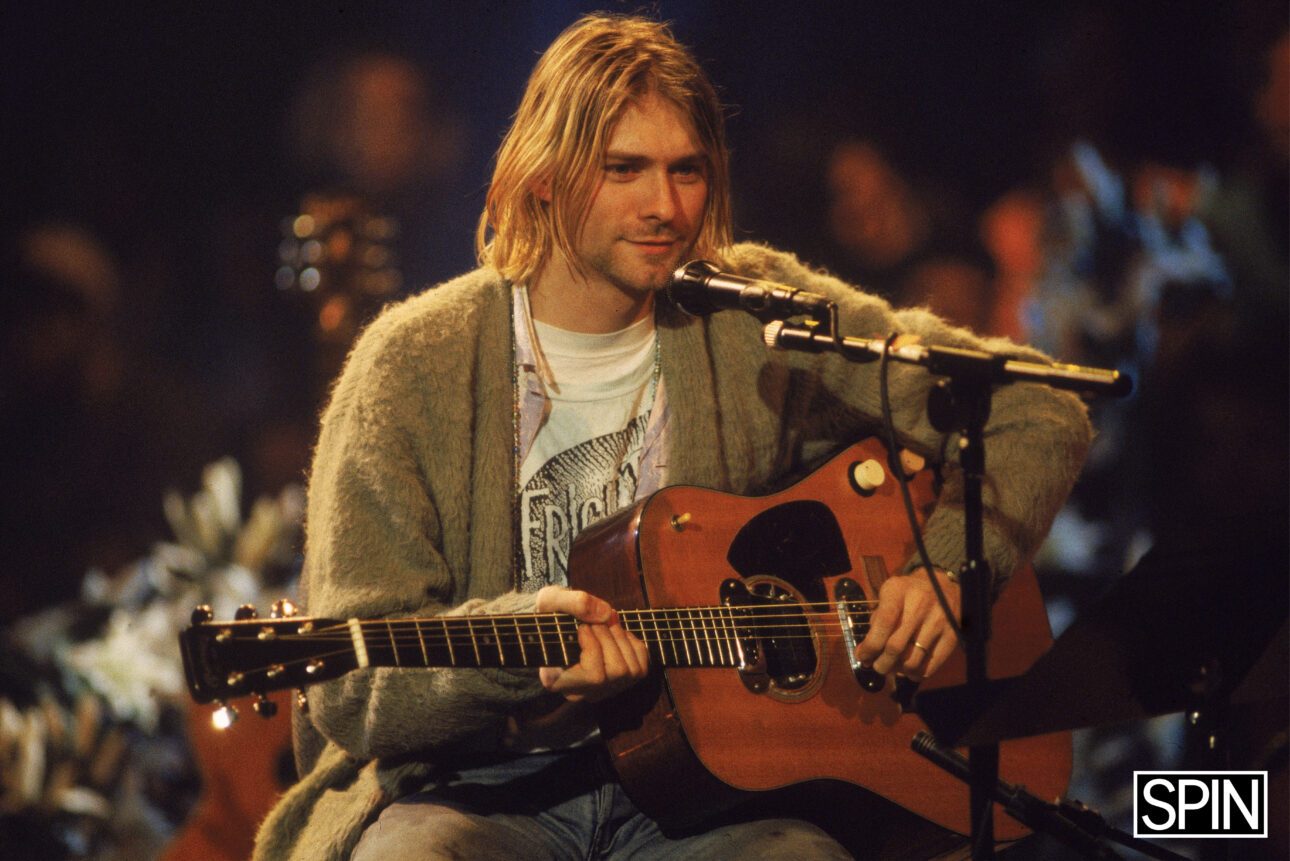

Photo Credit: Frank Micelotta/Getty Images

Photo Credit: Frank Micelotta/Getty Images

Photo Credit: Gutchie Kojima/Shinko Music/Getty Images

Photo Credit: Gutchie Kojima/Shinko Music/Getty Images

Photo Credit: Paul Bergen

Photo Credit: Paul Bergen

Photo Credit: Raffaella Cavalieri/Redferns

Photo Credit: Raffaella Cavalieri/Redferns

Photo Credit: Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

Photo Credit: Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

Photo Credit: Kevin Mazur/WireImage

Photo Credit: Kevin Mazur/WireImage

Photo Credit: Kevin Mazur Archive/WireImage

Photo Credit: Kevin Mazur Archive/WireImage

Photo Credit: Michel Linssen/Redferns

Photo Credit: Michel Linssen/Redferns