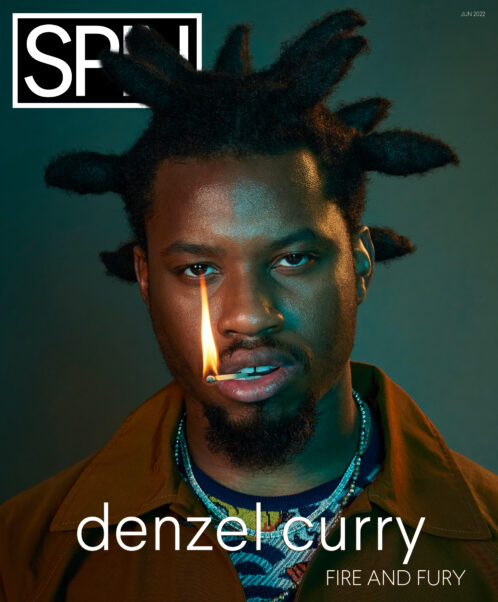

Though he didn’t blend with the sartorial elegance of his surroundings, his casual camel palette get-up was hardly eye-popping. But his signature style of dreadlocks, which can best be described as a series of jet black sand dunes, are even more captivating in-person than they are on-screen. The Dragonball Z parallels are impossible not to draw, though he lacks Goku’s hangtime. It feels somewhat as if a CGI character has just made its entrance into a live-action film.

Curry’s eyes eventually settle on his target—the breakfast table where we’ve been seated—and he makes his way over. His confused glances give way to reluctant flashes of a toothy grin; he’s happy to no longer be spinning in place, but perhaps not thrilled that his reward is two hours with a writer. Regardless, he bounds over and takes a seat as a dainty young lady, Emily*, introduces herself as the server. It doesn’t seem that Emily recognizes the multi-platinum-selling artist, and if she does, she’s quite skilled at discretion. Curry, however, slyly acknowledges that something about her piques his interest. Seconds later, he finds his opening.

*Emily’s name has been changed for privacy.

“Does that say Spooky Black?”

Emily, about to retreat from our table to tend to others, quickly takes steps back towards our table and squints her eyes, testing Curry to see if he’s trolling her. On the nametag pinned to her apron, below her given name, is another name in subtitle font: Spooky Black. “Yeah, I love him,” she says cautiously. Curry is in disbelief. He repeats the question. “You know ‘bout Corbin?” This time, opting for Spooky’s present-day moniker, which he updated in 2014. Emily reiterates her Corbin fandom and Curry’s toothy grin isn’t so reluctant anymore. He did not expect to be bonding with a complete stranger over one of 2010s rap internet’s most ironic obsessions—click here for context—yet here he was, genuinely geeked over the purity of this interaction.

Minutes later, Curry AirDrops her an invitation to a meet-and-greet he’s hosting that evening in Chinatown. Emily doesn’t promise that she’ll show up, but sincerely hopes to drop by. By this point, it’s wholly unclear who is the celebrity in this exchange.

A few moments later, Curry, impressed with his own gift of gab, playfully mocks the interaction. Oh my God, you know Corbin? Then, referencing his initial interest in Emily, he looks at me and smirks. “I called it.”

Denzel Curry is ready to cut through the bullshit.

His patience for the superficial has worn thin, eroded over time by loss, gain, grief, and therapy. He finds little fulfillment in many of the things that often characterize success at this point in his career, and even less satisfaction in the low standards currently acting as driving forces in music. He was cast into the spotlight as a teenager, established himself as a star during the most tumultuous epoch of modern-day hip hop—the dubious SoundCloud era, during which experimental artists used free file-sharing websites to launch mainstream-level careers and movements—and has proven to have the staying power that many of his peers did not. Now 27 and on the other side of a pandemic that presented him with the most challenging emotional hurdles of his young life, he is completely uninterested in Denzel Curry the idea: the rapper, celebrity and ego of it all. Instead, he’s turned his mind’s eye to Denzel Curry the person. The result is his most pensive and revealing record to date, Melt My Eyez See Your Future, an album he’s been plotting since 2018. There’s an argument to be made that Melt My Eyez is the most complete record in his catalog. There’s an even stronger argument to be made that it is the best rap record released this year.

“I was like, ‘Man, I don’t got shit to talk about,’” says Curry between sips of water. He’s describing the period of time that transpired between planning and releasing the album, citing depression and an inability to focus as the driving forces behind his writer’s block. The arrival of the pandemic conjured an omnipresent theme of soul searching in 2020 as the world retreated into quarantine. People were forced to reckon with themselves and their decisions more intimately than ever before. For many it was a novel experience, examining oneself without the obstruction of “outside.” Entertainers, despite their resources, could not buy themselves a different reality. Curry moved to Los Angeles in 2018 to put some distance between himself and the volatility of the streets of Miami’s Carol City neighborhood. However, like the rest of the world, he was shut indoors and, in several ways, reintroducing himself to himself.

“I had to stay with myself, which I never do, ‘cause usually I’m distracted by some things and I don’t like being alone,” he says. “This time it’s like, ‘Damn I’m alone. Damn I don’t know what to do with myself. Damn, I’m looking at everybody dying from a sickness. Damn, I’m looking at this movement that just happened. There were riots. The George Floyd situation’.”

The virtual disappearance of the outside world that Curry had been trying to draw inspiration from was the very trigger that began to dissolve his writer’s block. “I had everything to talk about at this point. I’m doing martial arts every day, honing in on my skills as a fighter, quietness, and going to therapy. The self-realization aspect of things.”

The album rolls this spirit of catharsis into a tightly-wrapped 14-song tracklist that plays out almost as if it were a therapy session, a succinct showcase of Curry’s storytelling, sharp wit, advanced lyrical ability and sonic range. In just 45 minutes, Curry takes himself and his peers to task, challenging the listener to fight through internal and external smokescreens to gain deeper understanding of self and, ostensibly, the world. “They smacked us in the face with that bullshit, now I gotta focus on getting my soul lit,” he posits on the chorus for “Worst Comes to Worst.” Elsewhere, on “The Last,” a brooding ramble that addresses society’s ills, Curry’s suggested response is slightly more aggressive. “Any day can be our last day, so much trouble in the streets that we need to buy an AK.”

His energy varies from accepting and understanding to frenetic and impatient, a reasonable spectrum of emotions considering the level of self-confrontation he’s undergone. Musically, the spectrum is just as vast: you’ll be hard-pressed to find many projects where Robert Glasper and Rico Nasty each deliver scene-stealing performances. This is part of what makes Curry unique. His skill set as a hip-hop artist speaks for itself, yet there’s so much more to him than writing sweet 16s. He’s gleefully covered Rage Against the Machine and held live jam sessions with Glasper that, sonically, are mutually exclusive from much of his catalog. “What drew me to Denzel was that he was a young guy who didn't give a fuck about trends,” says Glasper of their early encounters. “He's all about being honest and being who he is and I'm down for anybody that follows their own path.”

Fittingly, despite its range, Melt never feels incoherent. Even when mainstream stars like T-Pain and 6lack enter the room, they align with Curry’s agenda. T-Pain, of “I’m ‘N’ Luv Wit a Stripper” and “Buy U A Drank” fame, joins Curry on “Troubles,” where he laments the sobering struggles that accompany affluence and fame.

Also Read

The 30 Best Songs of 2022 (So Far)

But it’s on “Walkin,” the Kal Banx-produced lead single from the album, that Curry’s journey is best summarized. “Walkin’ with my back to the sun, keep my head to the sky, me against the world it’s me, myself, and I like De La,” he raps, paced by ethereal female improv (“La-da-da-da-daaa”) sampled from a 1973 Keith Mansfield instrumental composition. After the first 90 seconds, you already feel like you’ve heard a great rap song. However, moments later, the beat gives way to its skeleton: sample, snare and an urgent metronome. Suddenly, Curry is muttering what sounds like an introduction to part two. Then, it happens.

“CLEAR A PATH AS I KEEP ON WALKING, AIN’T NO STOPPING IN THIS DIRTY FILTHY ROTTEN NASTY LITTLE WORLD WE CALL A HOME.” Curry’s methodical march from the song’s first half is no more. He is now sprinting as if his head were on fire. In Dragonball Z lore, when Goku reaches his Super Saiyan state, balls of flame engulf his body as lightning dances about him, signifying that he’s reached a level of invincibility. On the second half of “Walkin,” Curry is ablaze.

As much as “Walkin’” feels like the onset of a new journey for Curry and signifies the culmination of one as well. His career is a testament to his perseverance, and an uncanny ability to communicate with his audience, which has supported him through each phase of his evolution. His debut mixtape, King Remembered Underground Tape 1991-1995, landed on the radar of South Florida native SpaceGhostPurp and his Carol City-based Raider Klan collective after its 2011 release. Purp, the noted punk rap enthusiast most known for fueling the early 2010s rise of the A$AP Mob—and then beefing with them soon thereafter—recognized Curry’s raw energy and talent, and it was on from there. As a member of Raider Klan, Curry’s buzz quickly transcended the local confines of Carol City. During his tenure, he released a slew of independent projects, most notably 2012’s Strictly 4 My R.V.I.D.X.R.Z., widely regarded as one of the best releases to ever come out of the Raider camp. South Florida standouts like Robb Banks acknowledge Curry’s influence in the region is akin to that of an OG, despite his relative youth. But in 2022, Curry has nothing to say about the fledgling portion of his career, despite the legacy he built.

“Don’t erase the history,” he says defiantly, locking eyes as he conveys the matter’s serious nature. “But they disrespected me.”

For some artists, establishing an identity after leaving a sphere of influence like Raider Klan can be challenging. For Curry, the transition was seamless. He’d watched his peers build a brand and insulate it with quality release after quality release—several of them his own—and take a local movement to national prominence. Musical descendants of what they’d created were sprouting all over South Florida, from Ski Mask the Slump God to Smokepurpp. When it was time for Curry to tend to his solo career exclusively, he had the advantage of being a rookie on the national radar, but a seasoned veteran of the SoundCloud generation, whose artists often sold tickets quicker, and more often than occupants of Hot 97’s primetime slots.

This shift couldn’t have come at a better time for an artist like Denzel Curry, who would rather pull his beloved dreadlocks out than call in Rick Rubin or Max Martin for a crash course in pop formula. But that didn’t mean his music and message didn’t carry widespread appeal. It is upon this basis that this period became the career launching pad for popular artists like XXXTentacion, Slump God, and Curry. Artists with little radio ambition, but the artistry and work ethic of a mainstream star, now had more avenues through which to thrive. Curry took advantage of this, and racked up plays on his early studio releases in the 10s-of-millions. Nostalgia 64 (2013) and Imperial (2016), two career-defining releases, were initially released to SoundCloud before being re-released on Spotify, Apple Music and TIDAL.

“What makes Denzel unique is his ability to always reinvent himself every project,” says his DJ, Po$h. Perhaps the only thing more constant at a Denzel Curry live show than the frenzied energy of Curry’s stage presence is Po$h, who has been working with Curry since they met 11 years ago. “He stands out because he doesn’t always try to do what others are doing. He’s an innovator not a follower.”

As major labels rushed to sign these fledgling stars, they demonstrated a noted lack of understanding of how to amplify the artist brands without altering them. Curry didn’t fall victim to these pitfalls. Radio continued to be as disinterested in him as he was in it, but that didn’t deter him from pushing his boundaries. He secured Rick Ross and Juicy J features for Imperial, a feat that even a mainstream artist with major label backing might find challenging. Most importantly, he’d done it without conforming to styles of music that weren’t genuine to him. Still, his goal was not and is not to be some obscure artist too cool to be enjoyed by a massive audience. He wants to make hits, his way.

“I’m 27, and I have three hits to my name independently. That’s great, but you got people on major labels with multiple, and it’s a struggle for me because I refuse to sell myself short. Some guy was telling me today I should sign to a major. So I said, ‘fuck no,’ and I put my hands behind my back. And I asked him the difference between a major label artist and a slave,” he says defiantly.

He pauses and observes me intently. Not because he’s thinking of the answer, but because he’d like me to provide it. I mumble something about major label artists getting paid more, and he shakes his head disapprovingly. “The shackles they put on major label artists? They glitter.”

Curry’s scheduled meet-and-greet later that day in Chinatown is set in Chinatown Fair Family Fun Center, a nostalgic arcade in a corner of the city that few people would go looking for one. The venue could fit about 40 people comfortably, assuming at least half of them are seated at arcade games, and not occupying the single-file corridor that runs through its lobby. By the start of the event, at least 300 people—mostly 20-somethings of varying ethnicities and backgrounds—had packed out the arcade itself, crowded around its entrance, and lined up down Mott St. and around the corner as they waited to meet the rapper.

Inside, three-quarters of the way down that single-file corridor stands Curry, immersed in the throng of fans who have reached the front of the line. His security is present, but not hovering. He’s close enough to at least five clamoring fans to get his chain snatched or to have one of his carefully shaped dread dunes snipped by a mischievous attention-seeker. The type of calamity that can come with the territory of being a hotly-coveted figure on the streets of New York City. Instead, Curry is noticeably comfortable as he welcomes excited greetings and random fans’ musings of their experience with his music, or shared affinities for Star Wars. At one point, a uniformed Amazon delivery worker reaches the front of the line and gleefully asks Curry to sign the back of his branded, blue vest. This is rewarded with excitable squeals from patrons waiting behind him, who rousingly approve of his decision to allow Curry to vandalize his work attire with “ULT” written in permanent black marker.

Minutes later, there’s a huge commotion outside the arcade’s entrance, leading me to believe that the venue has shut its doors to the meet-and-greet crowd, possibly leaving over 100 fans’ autograph-and-selfie dreams unfulfilled. The opposite is happening. Curry, unenthused with the piecemeal setup of the event, decides that he prefers to meet and greet all the fans waiting outside simultaneously. In what feels like the blink of an eye, a circle of fans opens up with Curry as its ringleader, looking as if he’s to lead a mosh pit at one of his shows.

Then, abruptly: “YOU.”

Curry selects a fan at random and challenges him to a game of Ninja. (The objective of the game is fairly simple: opponents begin the match in set positions that look like fighting stances. However, instead of actually fighting, the goal is to slap your opponent’s hand without having yours hit. It’s very much the flag football version of sparring. Which is not to speak condescendingly of the skill required. It’s just more of a stealth mission.) The fan cautiously approaches, prepared for the challenge ahead but wary of the fact that the resulting footage could help him go viral for less than favorable reasons. But with a crowd roaring its support and at Curry’s own encouragement, the fan readies himself for battle.

This process repeats itself for the better part of an hour, with fans hopping in and out of matches, sometimes two to three at a time. The lane of downtown traffic on Mott St. had been doing its best to work around the crowd that spilled into the street when Curry first emerged from Chinatown Fair. But now, thru traffic was almost obstructed by the widening circle of fans. Curry, completely in his element, encourages fans to challenge him, staring deeply into their eyes as he sways back and forth in preparation for opening strikes. He shrieks jubilantly when one of his opponents lands a well-executed blow to one of his hands, and argues questionable calls as if it were a real dojo setting. Even as fans scaled nearby scaffolding for bird’s eye views, things never got out of control. Traffic wove its way around the commotion, and Curry’s team stood nearby patiently, ensuring that each fan got what they came for.

“I think for one thing, it’s his use of experimentation,” says one young fan, as he inches forward towards the arcade’s entrance with his female companion. “He’s a wild card when it comes to Hip Hop. He doesn’t focus on one style, and he’s an aggressive force in how he pushes for what he wants to hear. He’s a dope presence.” The fan goes on to reveal that when he’s not listening to Curry, he’s enjoying acts like Travis Scott and Smino.

“And you feel like you’re getting something from Denzel that these artists don’t offer?”

“Yes, for sure.”

Curry attributes his still and mindful demeanor to the two things he indulged in wholeheartedly at the onset of the pandemic: martial arts and therapy. He has practiced Muay Thai for a good part of the last couple years, a style of martial arts native to Thailand known for utilizing movement of the entire body. For him, Muay Thai initially acted as a substitute for substances that he was working to wean himself off of, notably weed. He picked it at random, basing his selection on the proximity of the martial arts school to his home in Los Angeles. Eventually, it became part of his everyday fiber. “It levels me out,” he says. “That’s the whole thing with martial arts. It’s the teaching experience and the learning experience. That’s what it is for me, and it helps me a lot.”

Therapy helped save Curry. He likens the resolve he gains from it to a life-altering breakthrough. The only way he could deal with the grief that he’s experienced already. There’s his brother, Treon Johnson, who was killed at the hands of Miami-Dade police in 2014. Following a confrontation with officers, Johnson was tasered and pepper-sprayed. He would subsequently go into cardiac arrest and be declared dead at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. He was 27.

Of the handful of news reports available on the incident, none of them mention any mental health issues Johnson may have been living with. “My brother was going through it mentally,” Curry says of the incident, matter-of-factly, when I broached it at Sessions. “He had psychological breakdowns. Police need psychiatric evaluation of situations.” He speaks with the air of someone not who lacks emotion, but of someone who would rather not go there with a total stranger.

“How did it shape your personality? Your outlook as a man?”

“I just knew I was never going to get justice for that.”

There’s also the murder of XXXTentacion, one of Curry’s closest confidantes and collaborators. The two were introduced via a happy accident: a miscommunication led XXX to believe that he was to perform at a house party where Curry lived in South Florida in 2015. When that proved to be false, XXX and Curry worked through the brief tension that followed and began keeping in touch with each other about their careers.

Curry made it a point to listen to XXX’s early material, citing songs like “I Love When They Run” and “Fuck” as his entry points into his new friend’s artistry. Conversely, XXX took note of Curry’s rising profile while “Ultimate,” one of Curry’s biggest singles to date, made its rounds as Curry prepared Imperial for a Spring 2016 release. In virtually no time, they were the best of friends, and stood poised to be one of the more potent 1-2 punches out of the region. However, on June 18, 2018, XXX was murdered in his car. Footage of his limp body had somehow made it to Twitter. Curry was back in South Florida, just months after moving to L.A. for a brief visit when he got the news. Texts and phone calls alerting him of what happened didn’t initially register. “X got bagged,” read one of them. In disbelief, Curry asked himself aloud, “Bagged? What you mean, bagged?”

“When it was good it was good, but when it was bad, it was…” Curry’s train of thought derails slightly as he recalls his complicated relationship with XXXTentacion. He cherishes the times they shared together, but he is able to objectively speak to his late friend’s erratic behavior. Much of XXX’s legacy is defined by abuse allegations. At the time of his death, XXX was awaiting trial for multiple charges of battery stemming from a domestic incident with a former girlfriend in 2016. The details of the alleged abuse are gruesome. Considering Curry’s personal history with abuse, how did he reconcile XXX’s past with his own emotional journey?

“It’s between him, that girl, and God,” Curry asserts. “He used to tell me all the time, ‘I ain’t do it, I ain’t do it.’ Well, somebody had to do it!”

Then there’s Curry’s home life. Carol City had its welcoming qualities as a hotbed of island culture, but also an entrapping presence, with crime, violence, and an ominous element of the unknown seemingly around every corner. He speaks joyously of his parents, acknowledging that though his relationship with them takes work, there’s no mistaking that he gets much of his personality from them. “That anger, that little switch, I get from my mom,” he admits. “That calmness I get from my dad.” He speaks fondly of their family meetings, or the quality time he used to spend with his brother watching UFC—one of the reasons he took up martial arts—and the backyard brawls they would host that propelled his older brother Treon to local prominence.

When he was 6, Curry was sexually abused by someone he knew well. “I’ve been touched way before I touched my—,” he raps on “Melt Session #1,” the intro track on Melt My Eyez. Fittingly, “Melt” is produced by and features Glasper, a full-circle moment for the potent tandem. “I did not know about all the things that he revealed on Melt, it was news to me,” Glasper says. “Honestly, when I really listened to the rhyme in a real way I wanted to give him a hug. It explains so much and I'm happy that he's able to heal through his music and hopefully heal others through his music.”

Curry spoke publicly about the incident for the first time during an interview with The Breakfast Club, the incendiary Power 105.1 FM morning show, it’s something that he initially struggled to process, unable to address it or think about it without slipping into depressive episodes. Therapy allowed him to face his grief head-on.

“I didn’t want that to define me. It’s like Kendrick Lamar said, there are people hiding the hurt through their chains and tattoos. Just to show you that they weren’t this person.” Curry references a lyric from the Pharrell-produced title track on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, Kendrick’s recently-released fifth studio album: “Tyler Perry the face of a thousand rappers, using violence to cover what really happened.”

“It’s more psychologically damaging when you [mask it],” he says. “I was molested before I even knew what the term molested meant. Like, that shit is crazy.”

“Did you know it was wrong when it happened?”

“No”

“How long did it take you to realize?”

“When I hit 12. I got to middle school, and that’s when I figured it out. I just remember breaking down crying, because my mind had developed enough to understand the scope of the situation.”

It got to the point where thoughts of suicide had made their way into his consciousness. “One day I wanted to kill myself. I just didn’t want to live with that shit.” He submerged himself into therapy, experiencing emotional breakthrough after emotional breakthrough, trying his best not to dwell on trauma. And it’s worked. Or at least, it’s started to. “I can’t say I’m fully over it, but I’m comfortable with myself.”

“Mike Tyson is the baddest fighter on the planet, and this happened to him,” Curry says, with a subtle-but-unmistakable air of triumph. “I know I’m destined for something great because I’ve been through so much shit.”

“Fake fans,” blurts Curry mockingly, as the van carrying him and his team from the media tent back to Artist Village on Day 2 of the Governors Ball music festival in Queens, chugs its way around the perimeter of the festival site: the massive parking lot at Citi Field, the home of the New York Mets. He’d just encountered a couple of eager festival goers as he made his way through media interactions, and one of them hesitated tellingly when asked about his favorite Denzel Curry records. Curry picked up on the fact that the fan was waiting on a cue from his friend, which slightly peeved the rapper. Jokes about what the photo he took with the fans would be captioned ensued, with a member of the convoy tossing out, “Building with big bro,” as an idea.

As Curry mills about his trailer, working on setting aside time for a pre-show nap and socializing with the friends and friends of friends strolling in and out of the trailer, he has an opportunity to address his Twitter takedown of all things mediocre from May which included a denouncement of new albums from Drake and Kanye West, slurs, and fans who prefer his older material. (A fan tweeted that Curry’s music used to inspire him to live, and implied that it doesn’t anymore. Curry responded to the fan with a simple directive: “So die.”)

As instigative as it sounds, his comments on Drake and Kanye were interesting for reasons other than who he name-dropped. It was the why. “I was looking forward to Drake’s album, ‘cause Drake always got something. But then, when you get them albums, you’re like, ‘What the fuck are you doing?’” He cites older Drake albums like Take Care and If You’re Reading This, It’s Too Late as examples of the quality he expects from the megastar, and then turns his attention to Kanye and the latest of his albums to be released to streaming platforms, Donda. “We don’t even really need to talk about Kanye West, it’s Kanye West,” Curry starts, acknowledging the legendary Chicago native’s legacy.

“But for them to go out, and go against each other and make that subpar work with the resources they have. These are the same producers it’s hard for me to reach out to because they don’t see the return. You’ve got all these resources, and y’all made subpar albums. I had limited resources, and I made a great one. That shouldn’t happen.”

When he takes the stage at Governors Ball, what was initially a somewhat sparse pre-show crowd quickly thickened into a mob of people moving in unison as Curry and Po$h pranced around the stage in rhythm to “Walkin,” drawing energy from an increasingly raucous crowd and giving it right back. Each and every song was met with the type of response that one would expect from hit records, despite none of them landing on the Billboard charts. Stage performances from some of the most central and popular acts in hip hop lack the type of energy and intensity exhibited at Curry’s Gov Ball set, but as he notes, the industry is reluctant to treat him as an A-list artist.

“Everybody just looking for something to benefit them. I see the clout chasing,” he says. When “Walkin” was released, despite its obvious potential, it wasn’t immediately listed on RapCaviar, Spotify’s signature playlist for big ticket hip hop releases. “They put me on the alternative list,” Curry says, slightly rolling his eyes as he lounges in his trailer. “It felt like they pre-slated me for that. Like, ‘Yeah, he’s alternative.’”

“This ain’t alternative n***a. This rap.”

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft

Photo Credit: Robert Ascroft