When it comes to the vast, undulating history of rock music, you’d be hard-pressed to find a band as innovative, invigorating, provocative and perpetuating as the MC5. Oozing up from the mean streets of Detroit in the chaos and turmoil of 1960s America, the Motor City 5 were a rebellion not only against the establishment but also a retaliation to an exuberant counterculture still sporting rose-colored glasses.

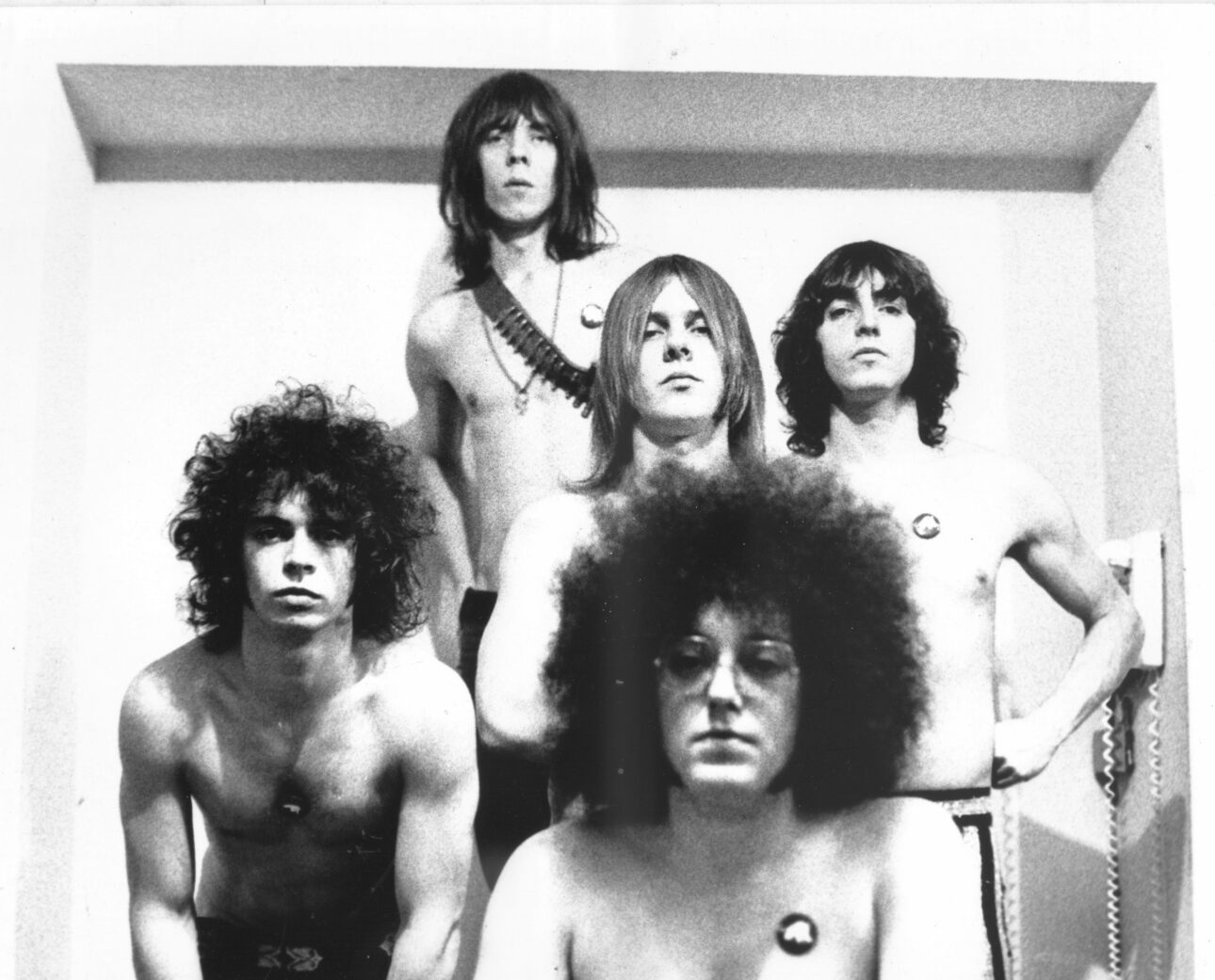

The MC5 was, and remains, a sonic revolution, one of cultural prowess and political scope. Consisting of Wayne Kramer, Rob Tyner (1944-1991), Fred “Sonic” Smith (1948-1994), Dennis Thompson and Michael Davis (1943-2012), it was a quintet of childhood friends and kindred spirits — the band’s motto, more so personal creed, being “all for one, one for all.”

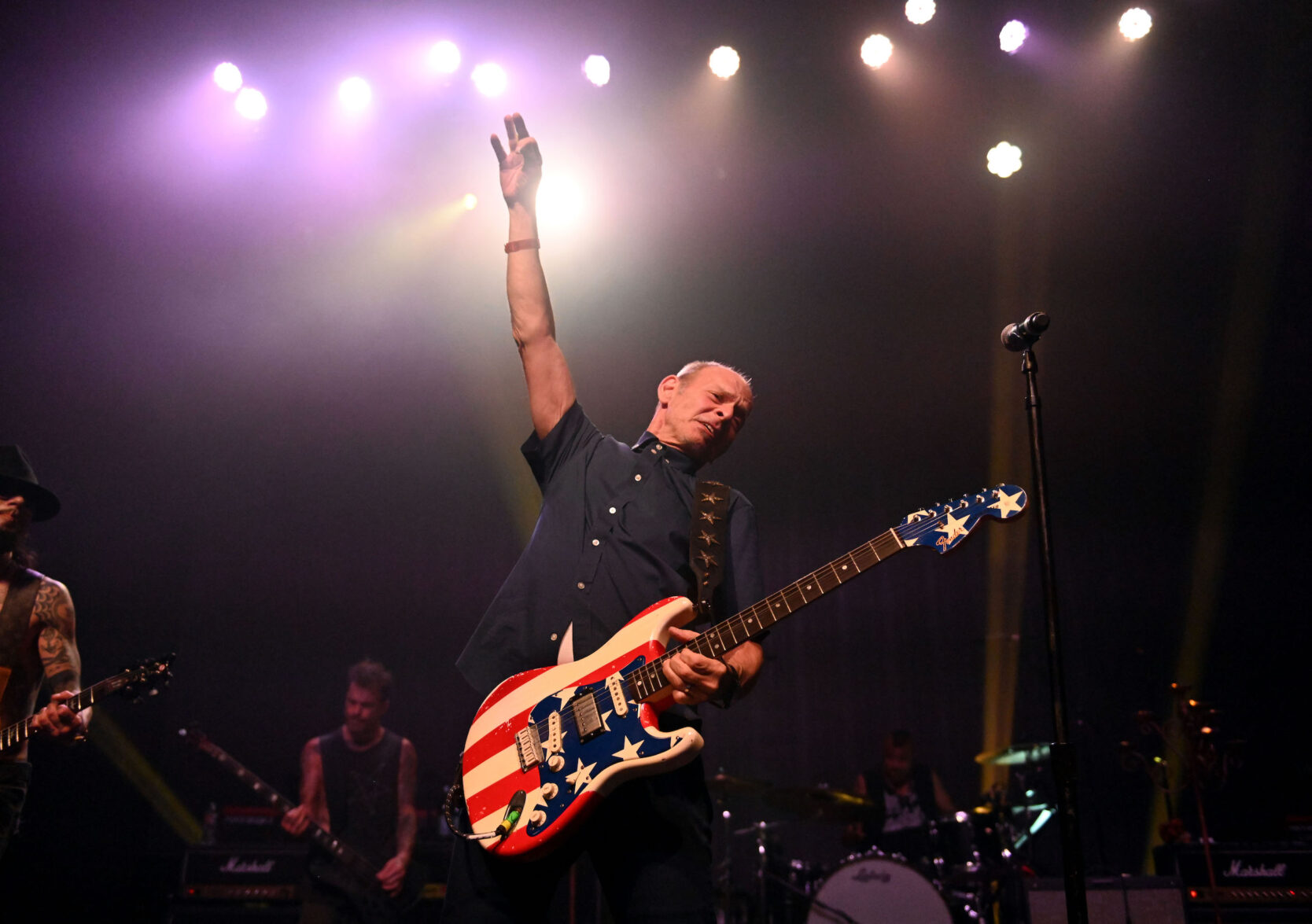

At the core of the group was Kramer on guitar. With his signature stars and stripes Fender Stratocaster, Kramer roared onto the stage, his shrieking tone echoing the anger, frustration and confusion of so many of his peers across the country. Kramer looked at his instrument and the MC5’s platform as a catalyst for real, tangible change, whether at home or abroad — a deeply-held sentiment that remained with him until his death on Feb. 2, 2024, at the age of 75.

Without the MC5, the trajectory of hard rock, punk and metal would be vastly different today. With them, they’re a melodic bridge between the Kinks of the mid-1960s and the birth of punk a decade later — the missing link between the raw power of the Stooges and the anarchy of Rage Against the Machine.

Throughout his trials and tribulations, whether personal or professional — including a hard-fought battle with drug addiction and a four-year stint in prison in the 1970s — Kramer’s continued resolve was one of compassion and understanding. He used his helping hand to uplift and not punch down.

In this never-before-published interview conducted on Halloween 2017, Kramer talked at length about where we stood as a people in the United States, what he’s been able to do with his nonprofit Jail Guitar Doors and, ultimately, the legacy of the MC5 and their eternal flame of passion and purpose.

SPIN: Beyond the fact of the MC5 being nominated again to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, I also have so many questions to ask you about what you think about the world today, It seems like everything’s going on all at once.

Wayne Kramer: Yes. We’re going through interesting times.

What do you think about what’s going on right now? Sometimes, I approach it with, ‘Nothing’s the same, everything’s the same.‘

Well, clearly the most amusing and troubling thinking comes from the highest level of power in America — the presidency. And I think the framers built in some protections that may help us survive without too much damage being done. But, I’m not sure.

Especially someone like yourself, who was not only politically active, but also lived through the Nixon years. It almost feels kind of like déjà vu.

Except that this guy is woefully underequipped. I mean, Nixon at least had served in government and understood norms. And certainly [Nixon] was a war criminal, crook, convicted felon, a liar and tried to subvert the entire nation. But [Donald Trump] is a little bit different. They both have grave mental and emotional difficulties.

And paranoia.

Yeah.

It’s also weird, too, when you look at it [today, where] Nixon kind of looks like a liberal, in terms of his environmental policies.

Well, there’s a lot of things that he did that, in retrospect, weren’t terrible. But then, it was all undone by his cunning, illegal and unethical approach to life and politics — much the same as the current resident at the White House.

Being someone who played outside at the Democratic [National] Convention in 1968 [in Chicago], what are your thoughts about the fact we’re still dealing with these same issues of police brutality and racial inequality? Is it just the human condition throughout time, or that we’re dealing with these same issues 50 years later?

My sense is that things don’t change as fast as we’d like them to. The issues of corruption, race and political expediency — these things are going to take some time. On a lot of levels, we’re doing better than we ever have. But, there are still major challenges that are clearly defined today. Trump represents a slice of the American psyche — that racist, small-minded, xenophobic mentality. It is part of the American fabric.

Where are you right now in your activism, in terms of prison reform, drug addiction and counseling?

Well, the work we do in Jail Guitar Doors is two-tiered. On one level, we operate on a people-helping-people basis, where we provide instruments in prisons to use as tools for rehabilitation, to help people figure out what went wrong and learn new strategies to avoid reoffending.

Recidivism.

Yep. And that’s going very well. Our instruments are in 105 American prisons. We have songwriting workshop programs across the country. We’re on seven California prison yards and in the California Youth Authority. We’re setting up a program now at Rikers Island. We have one in the Massachusetts Youth Authority, in Chicago at the Cook County Jail and here in L.A. at the Los Angeles County Jail. So, all that work is moving forward. I think corrections professionals have started to realize that if we don’t help offenders change for the better while they’re in custody, they will most certainly change for the worse.

What’s your take on the opioid crisis and the privatization of prisons? What are we doing wrong as a society trying to correct these issues?

Well, that ties into the other tier of our efforts, which is legislative. There has to be a political goal, a legislative goal. At the end of the day, that’s what we’re fighting for. In terms of the opioid crisis, first I think it’s helpful to realize that this was big pharma that created this. This was not brothers on the corner slinging crack. This was white men in high offices of power constructing sales programs that put profit ahead of people and, in fact, knew full well that they were going to inflict terrible damage on regular, everyday people. And they did it anyway. And they did it with the approval of the political structure. The first step is to realize who the bad guys are here. It’s certainly not the addicts. They’re people that need help. Again, it is the perniciousness of big business that puts profit ahead of people.

Are you optimistic about the future?

To quote one of my intellectual heroes, Antonio Gramsci — ‘The [challenge] of modernity is to live without illusions and without becoming disillusioned.’ See the world the way it really is, and then go from there. Make a decision to do what you can to make a difference. Listen, people made this mess. And if people make a mess, people can clean it up.

On another note, the MC5 were nominated for the third time to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Is it one of those things you’re not going to lose sleep over?

Yeah, that’s fair.

In terms of the real message and attitude of the band, I would think the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame would be the furthest thing from their mind.

Well, it’s always nice to be recognized for your work. And I always appreciate it when somebody says they like a record or a song, a gig or an idea or something that I came up with. It’s tough with a thing like the Rock Hall because you can’t separate it from the economic interests. It’s hard to quantify. I mean, in sports, if a guy was a heavyweight champion of the world, he accomplished that. You can see it in his track record or in baseball. But, what are the statistics in rock? Is it record sales or is it influence? Art doesn’t lend itself to [that] — it’s very subjective.

In my opinion, as long as the MC5 and Steppenwolf are not in there, then it’s not really the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Well, listen, there’s a small group of people that were at the core of Rolling Stone magazine and later at the Rock Hall. And that group of people never embraced the MC5. They couldn’t wait to get rid of the MC5. And Jann Wenner is still at the core of that. I don’t think he ever liked the band, and I don’t think he likes the band today.

If the MC5 gets elected, does that mean you have to applaud the Hall of Fame now?

Yeah, right. Any organization that would have me as a member, I refuse to join.

I’m going to run some names by you and I’d like to hear your thoughts on what you remember most about that name. To start, Rob Tyner.

A genius. One of the most creative, original artists of our time. Really a firebrand and visionary artist who could see the future and work diligently to try to make that future real.

Fred Smith.

Fred Smith was my boyhood best friend. We learned how to play guitars together. And I’d like to think that we pioneered a two-guitar approach that was unique and that was as important as any of our contemporaries. I think Fred was developing into a master songwriter and storyteller. It was just heartbreaking to lose Rob and Fred so early.

Michael Davis.

Michael was an artist at heart. He was a visual artist, a painter. And he returned to painting later in life and started to rediscover his real strength. He was my dear friend for a long, long time.

And though he’s still alive, what first comes to mind when you hear the name Dennis Thompson?

Dennis is one of the most formidable percussionists. He has been for 50 years. And he chooses not to do much. He doesn’t play out and he doesn’t want to lead a band or anything. He doesn’t want to tour. He was the guy who was able to put a lot of thinking together on the drums that no one else had put together, you know? He listened to Sun Ra and Elvin Jones. He listened to Charlie Watts, Keith Moon and Mitch Mitchell. He was able to put these things together in a way that no one else had done before, and to take it further than certainly rock drummers had ever taken it. He had the ability to play outside of time, which was just genius in my opinion.

What’s your relationship with Dennis these days?

Oh, it’s fine. We talk every few months or so. We’re still close, or as close as you can be in that we live on different sides of the country and we don’t really do anything together anymore. But, he’s my boyhood friend and always will be.

Do you get back to Detroit at all?

I do. We’re trying to get a Jail Guitar Doors program off the ground in Detroit. We’ve already got instruments in one of the Michigan Department of Corrections prisons and we’re trying to get a program going in the city of Detroit itself, in the Wayne County Jail.

You grew up in Detroit in the ‘50s and ‘60s. One could surmise that was the symbol of America post-World War II as an industrial mecca. What’s it like these days when you drive around?

Detroit is the American Pompeii. It’s ruins. It’s square mile after square mile of empty lots and neighborhoods I grew up in that were thriving. Retail and residential neighborhoods are gone. It’s [Hurricane] Katrina-level destruction. When I grew up, there were almost two million people in the city of Detroit — this year there’s less than 700,000. They have no rush hour in Detroit.

Over the course of 50 years, [Detroit] represented the two extremes of the American Dream.

Yeah. Capitalism on both extremes.

You’re turning 70 next year. Are you having any full-circle moments these days? Any rebirth in your thought process?

Of course. It’s kind of a milestone. Who’d thunk it? I ponder my own finitude. I try to figure out who I am and how did I get to be who I am? And then, I have a young son. He is the world to me. He’s just bursting with enthusiasm for life. So, I get to see everything in a very realistic and clear way. The world — it’s his world now. He’s going to take it over and he’s going to have to deal with all this stuff.

It’s almost like time is all one thing.

Time is one thing.

Now that the MC5’s music has crossed the half-century mark, how has the music aged, and how is that message resonating with you?

Well, it holds up because what the band represented, at its best, was a direct connection with people’s concerns and the sense of possibilities — that there could be new music or new politics or a new lifestyle, new culture. That, with effort in full measures and going all the way with your ideas, you can actually make something happen. One person can make a difference. A handful of people can make a big difference. A couple dozen people could change the world if they were organized and committed.

What has a life playing music, creating music and meeting people from all walks of life taught you about what it means to be a human being?

To be human means to be stuck in tension between the beast and the angel. I’m never fully a beast and I’m never completely an angel. But, I’m in the middle there somewhere — imperfectly perfect.