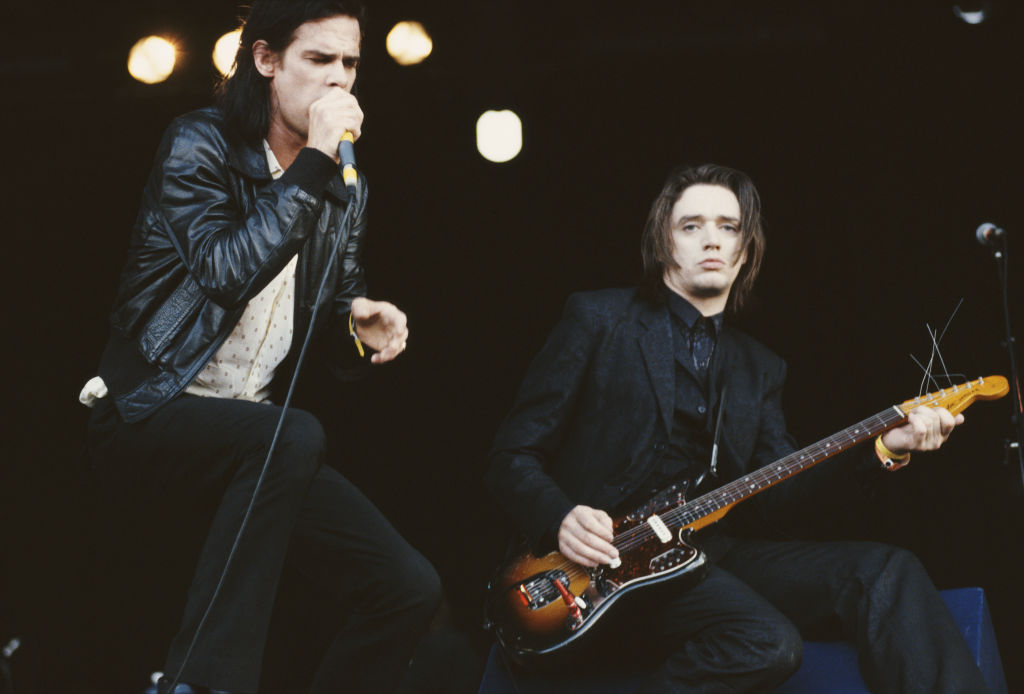

Mark Mordue’s best-selling, internationally published biography of Nick Cave, Boy on Fire, spans the singer’s infancy through to him landing in London in 1980 as a young wrecking ball with the notorious Birthday Party, dubbed the most violent band in the world and now the subject of acclaimed documentary Mutiny in Heaven. Mordue has spent decades in a persistent slow dance of conversation and revelation with the singular Cave, and in this extract from the Boy on Fire’s prologue, we experience the awkward, sporadic, but oddly honest beginnings of that flow.

The first time I ever spoke to Nick Cave was in a phone interview to promote his second solo album, The Firstborn Is Dead (1985), an ominous, blues-affected work that sanctified the birth of Elvis Presley and thereby rock ’n’ roll itself in quasi-religious, apocalyptic terms. Our conversation around the recording was as dry as spinifex, so slow and spacious it sometimes ceased to exist. As if Cave could not be less interested in what I was asking or saying and never would be. Given his notorious hatred of journalists back then, this made for an uphill experience. I put the phone down with sweating palms and a sinking feeling in my heart. What a failure.

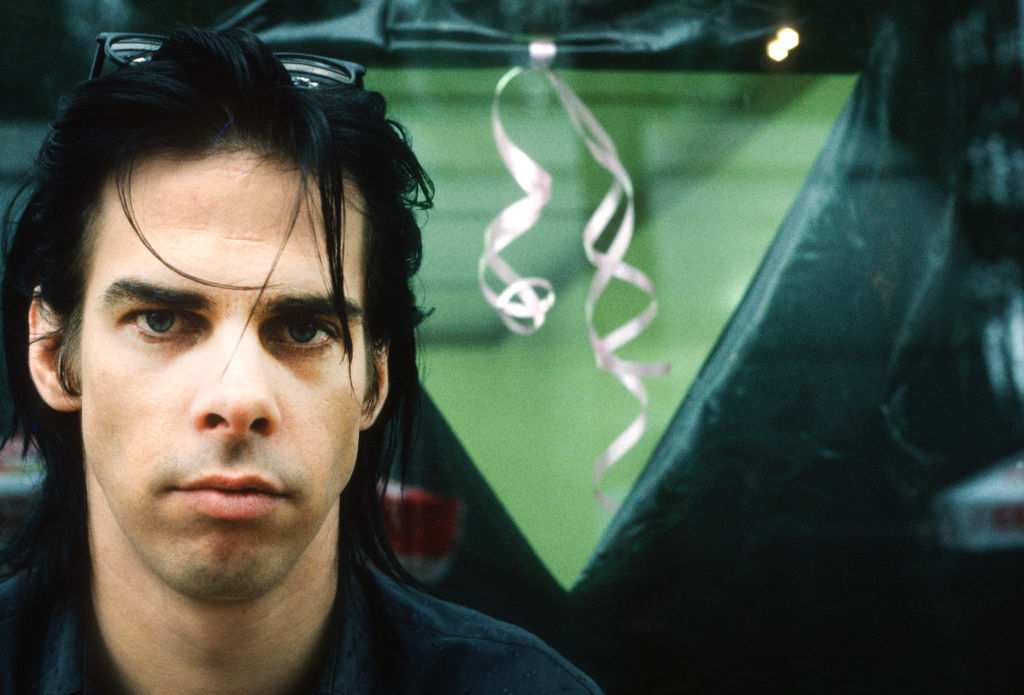

Dealing with Cave again, let alone meeting him in person, was not something I looked forward to. In 1988 I nonetheless lobbied to interview Nick Cave for Sydney’s On the Street. Second time lucky, I must have been hoping. Face to face he had to be more approachable than that distant voice on an echoing telephone line. Besides, he was the pre-eminent Australian rock ’n’ roll artist of his day. This made him hard to ignore.

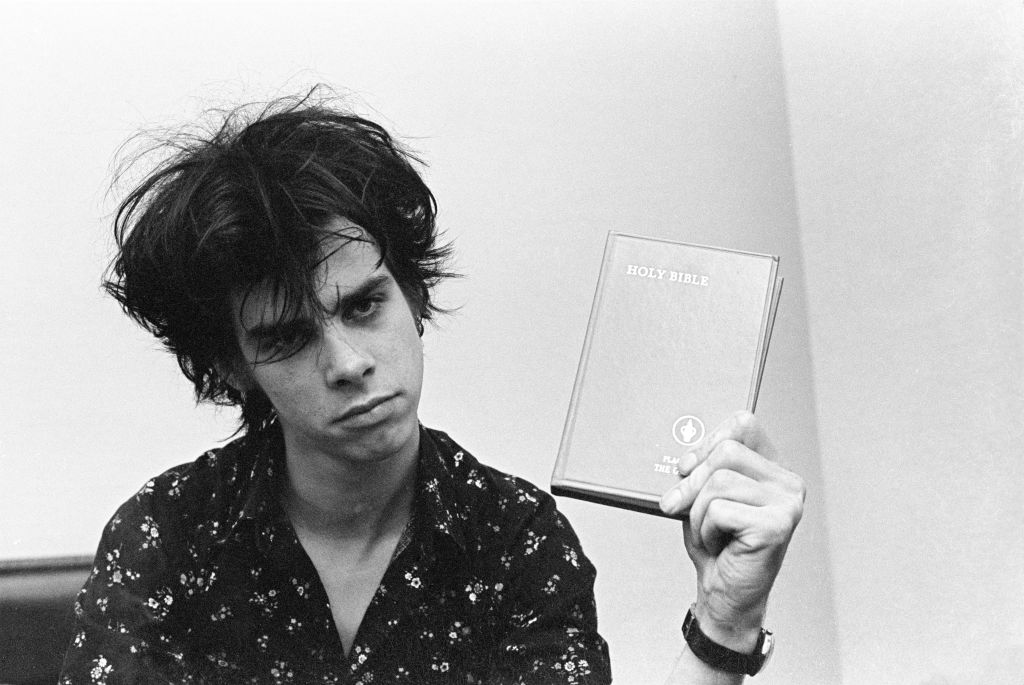

Cave was in town to read from and preview a much anticipated literary work in progress, a book that would become known as And the Ass Saw the Angel (1989). He’d already gone so far as to declare himself “more of a writer now,” disowning rock ’n’ roll for its lowbrow qualities and Pavlov’s-dog audience responses.

I was given a laneway address for a warehouse located directly behind Sydney’s somewhat alternative and bohemian gay strip, Oxford Street. Cave was apparently holed up there with a girlfriend or a dealer or criminal acquaintance: rumors varied, depending who I spoke to. As always with Cave, rumors were all around him, as if his every movement across town were hotwired into the gossip chambers of inner-city Sydney conversation. The only other wave-making machine of this kind that I would ever know was Michael Hutchence. It was as if you could feel their presence rippling through the city from the moment their flight hit the tarmac and they entered, half in secret, into our closed little world.

When I knocked on the door of what looked like an old garage, a key was hurled to the road with a vaguely familiar shout hovering invisibly on the Sunday-afternoon air. As I let myself in, I heard footsteps on the wooden ceiling and the creak of a trapdoor above. At the top of the ladder-like stairs that rolled down to meet me with a thud there was now a hole in the ceiling where Nick Cave himself stood, bathed in backlight. He beckoned me upwards like some awful figure in a B-grade horror film about a journalist come to interview a terrifying rock ’n’ roll vampire. I gulped and set forth on my way to meet my Nosferatu.

Once I arrived upstairs, the atmosphere changed immediately. Cave was a solicitous host, while a young woman I took to be his partner bossed him about as if I had just entered a Goth version of the British comedy George and Mildred. “Get Mark something to eat, Nick,” she said briskly. A large serving of the very best fruits was put before me – grapes, lychees, melon, apple – all prepared and presented in a grand manner.

As Cave was about to seat himself and enjoy some of this banquet, his partner said, “Did you offer Mark some coffee, Nick?” Again he rose, mock lugubrious, stick-insect angular. He went over to an old metal funnel attached to a wooden workbench, poured in some coffee beans and began to slowly turn a handle: “Grind, grind, grind, it’s the story of my life.”

With a variety of expensive biscuits now also arrayed before me, I was soon thanking the couple for their surprising hospitality. Cave asked me why it should be so unexpected. An evasive answer seemed tactically unwise, so I mentioned the Prince of Darkness thing around him, and his reputation for treating journalists poorly. “Who says that?” he asked, a little surly. “Why, the NME [New Musical Express] …” I began to say, in reference to the influential British music paper of the day. “The NME!” he barked. Cave began to grind the coffee beans with much greater intensity. His partner looked at me and said, “Don’t get him started.” To Cave she called out in a calming voice, “Now, Nick …” Cave ground on, taking it out on the beans: “The NME!”

Finally he came back over to us with a large silver coffee pot steaming with his efforts. A set of fine china cups were ready on a matching silver serving tray. Mid-pour, Cave lost focus, the coffee slowly streaming out of the spout and around—but not into—the cups in an ever-widening circle, the tray filling with black liquid as if it were a swimming pool, until he snapped back into consciousness and finally found the cups as well. Completing the task at last, Cave then asked me with all the decorum he could muster: “Would you like milk or sugar with that?”

The next two and a half hours felt rather like an interview taking place under similarly dark water. Each question seemed to demand huge reservoirs of concentration from Cave, not to mention frequent pauses and micro-sleeps. Cave’s sometimes thin and creaky, sometimes sonorous and self-consciously refined speaking voice certainly had its hypnotic qualities. I felt suspended, unsure of what to do, or even how to leave. To be honest, I’m not sure the encounter ever quite ended so much as faded away. With everyone heavily relaxed, I departed once more through the floor.

It was yet another Cave interview in which I felt I had somehow failed, despite Cave’s very best efforts to help me. This was largely because I didn’t really understand how to write up what had happened. I also dreaded sitting down and transcribing the interview tapes, a process that would demand even greater leagues of passing time from me all over again.

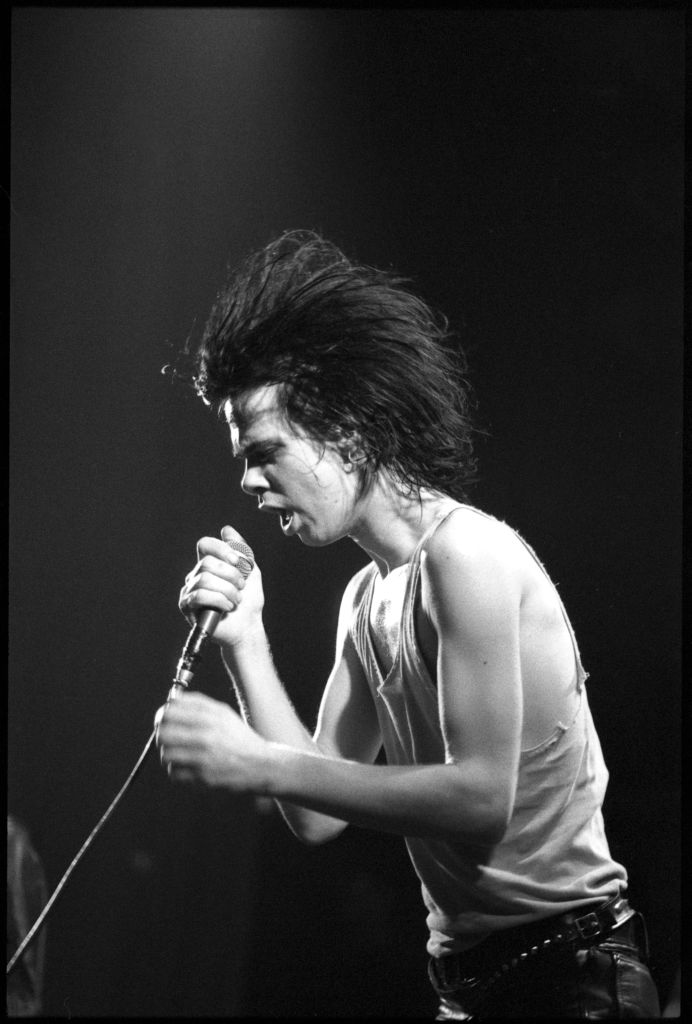

Two nights later, on stage at the Mandolin Cinema in Sydney’s Surry Hills, Cave would recite from sections of his work in progress while an ambient soundtrack rose and fell with suitably ominous and dreamlike effect around his reading voice. Looking every inch the ‘Black Crow King’ (one of many self-referential character songs that would add to his mythology, despite the satirical swipes it took at his image and those who subscribed to it), Cave did not so much walk onto the stage as dangle, stoop and hang in the air as if from unseen strings. He would eventually fall off the stage. And yet the cinema was full to the brim with his fans, a sellout performance over two nights, and a success in terms of the mood created by him reading from what appeared to be a credible, black-humored, Faulknerian work of fiction well on the way to completion.

In 1994, six years after these readings and our warehouse encounter, the boot would be on the other foot, when I once again spoke to Cave, this time over the phone. He’d been living in São Paulo, Brazil, and—by all public accounts at least—was as clean as a whistle. For me it was an early-morning interview. Very early. Unfortunately, I’d broken up with my girlfriend the previous night and not been home, to sleep or otherwise, barely brushing in the door to take Cave’s call. Thank God I’d prepared the previous day. When Cave asked me how I was, I told him at great length: that I’d been out wandering all night, that I’d been here and there, felt this and thought that, a long, wild, emotional ramble that ended with me saying I loved his new record, Let Love In, and finally asking if he had a favorite walk he liked to take in São Paulo.

Cave took this all in with a long pause and slight grunt—and we began to talk. It was a great interview and I liked him a lot. He seemed completely non-judgemental about my ‘condition’; in fact, I’d say he was both courteous and curiously amused throughout. As for his answer to my opening question: “Well, I make my favorite walk daily. Which is up to my local bar. Out the door, up the street, past the junkyard where the chickens and the old junkyard dog sits. And up a steep hill to my favorite bar, San Pedro’s. There’s this giant barman there who is the fattest guy I’ve ever seen. He is constantly described by locals as a huge woman, but he’s a man with a mustache. He looks more like a giant baby to me. I sit there and read, drink and contemplate the meaning of life. Then I walk back down.”

A few years on I would meet Cave again, in 1997 in a rather sterile, fluorescent-lit room at the offices of Festival Mushroom in Sydney. Cave remembered me well enough, but his mood was odd and, I realise now, highly vulnerable, as The Boatman’s Call—a raw and revealing album that revolved around his break-up with Brazilian partner Viviane Carneiro and a wounding affair with PJ Harvey—was about to be released. None of that was public knowledge yet. I nonetheless asked him, almost randomly, if he thought the love of a good woman could redeem a man. It was a question that seemed to arise out of his lyrics and what they implied across the record. Cave looked at me as if I were a total fucking idiot, and then away at the white wall as if he were a hopeless and godforsaken case himself. “How the hell would I know?” he said. And then he looked back at me and waited for the next question.

© Mark Mordue, 2020. Extract from Boy on Fire: The Young Nick Cave by Mark Mordue, published by Allen & Unwin, RRP $17.95. A book trailer for Boy on Fire can be viewed here, and Mark Mordue’s substack is here.