Is there anything more romantic than a flowy-haired, misunderstood musician who left a beautiful corpse? That’s the stereotype ascribed to Nick Drake, the immensely talented singer-songwriter and guitarist who died of an overdose of prescribed antidepressants at the age of 26 in 1974.

Drake never received the recognition his music deserved while he was living. The more years pass, however, the greater his legend looms, at times becoming more a creation of his ever-growing fanbase’s imagination than any semblance to the actual person.

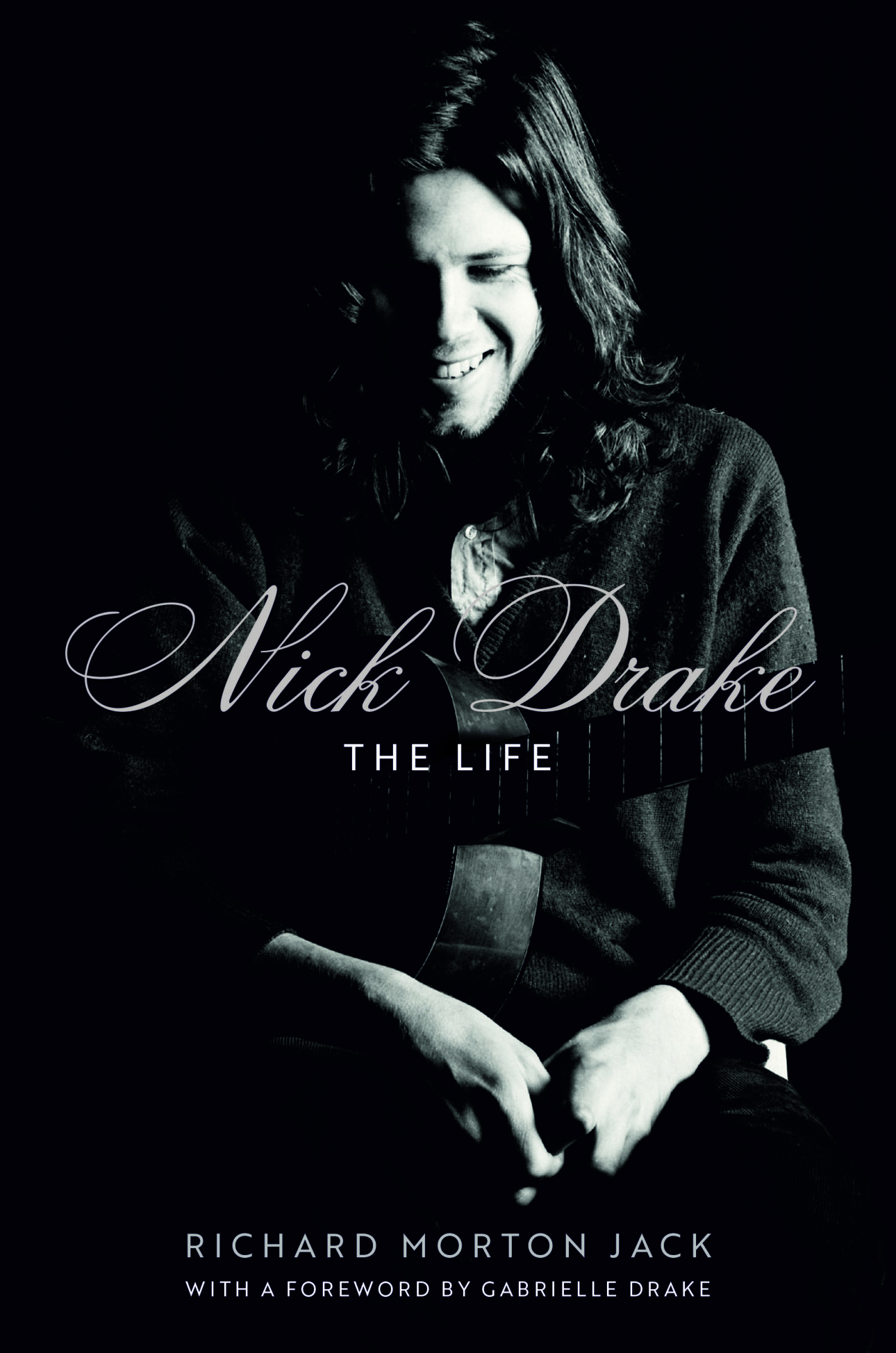

Richard Morton Jack has set the record straight, so to speak, with his comprehensive biography: Nick Drake: The Life (released last month). Sourced from friends, family, colleagues, other biographies (a number of which are listed in the exhaustive bibliography) personal diaries, letters, essays, interviews, press clippings, films, and anything else he could get his hands on, Jack provides an oral history of Drake’s day-to-day, from when his parents met through to post-mortem.

Almost 600 pages in length, one feels like the fly on the wall of Drake’s life as Jack provides the minutiae of his daily existence. Drake was born into an affluent family flanked by servants and with generous pocket money. His family supported him financially as he struggled with all aspects of his life. His parents and sister, actor Gabrielle Drake, exhibited unwavering determination in helping him with his mental health issues. His friends, similarly, wanted to help, although early on they repeatedly say Drake didn’t show signs of mental illness.

Gabrielle has penned the foreword to Nick Drake: The Life, and with it, co-signed the biography as the true story of her brother’s life. As the owner of Drake’s estate, Bryter Music, Gabrielle, along with Cally Callomon who manages the estate, gave Jack access to extensive personal items. These include the aforementioned letters and diaries, which provide a personal insight previously unavailable. Gabrielle and Callomon themselves published Remembered for a While, a collection aimed at dispelling the fictitious mythology built around Drake in 2014. It’s Nick Drake: The Life, however, that Gabrielle considers the definitive narrative biography of her brother.

For his part, Jack says it is a “privilege to be trusted with the task” and shares the process of putting the book together with SPIN.

Prior to embarking on writing this book, what was your personal connection with Nick Drake and his music?

I encountered Nick’s music as a teenager in the mid-’90s. By that time, he was already canonical, so it didn’t feel like I’d joined a secret club in the way it must have 10 or 15 years earlier. Nonetheless, I found his music very alluring: melodic and varied, enigmatic and mysterious, yet with a warm core.

You have such extensive input from people in Nick’s immediate circle of friends and family. How much of that is first-person accounts and how much of it is sourced?

Before I began interviewing, I read/listened to/watched every scrap of interview relating to Nick that I could find, and cross-referred it all to expose any conflicting information that I would need to follow up on. Patrick Humphries and one or two other writers very generously gave me their interview transcripts (including some valuable ones with people who are no longer among us), which hugely helped. When I began to carry out my own interviews—around 200, in the end—I deliberately avoided asking people to repeat what they’d already said, and focused on what else was lurking in their memories.

How did you find the people you spoke to as far as their recollections of Nick? From the book it sounds like everyone had a pretty loving attitude toward him.

One of the many poignant aspects of Nick’s early death is that his friends have carried a lifelong sense of regret and even self-reproach. I found them all very open to remembering him, perhaps partly because I spoke to many of them during the COVID lockdown, when they were especially susceptible to self-reflection. In addition, those who love Nick had all been outraged by one particular book, statements in which have been repeated on Wikipedia and elsewhere, so they wanted to set the record straight as far as that went. And yes, it seems that everyone loved Nick, even if they found him baffling and even exasperating in certain ways.

You recount the contents of letters, reviews and write-ups in music press from around the world. I know some of this was made available to you by Nick’s estate. Where else did you find the information?

I have my own massive library of music magazines and newspapers (both mainstream and underground) from the ‘60s and ‘70s, and combed those for relevant information. I also looked through many local newspapers in the British Library.

Mental illness aside, I found what you said about Nick’s affluent background perhaps not giving him the toughness needed to succeed as a musician quite interesting. Can you expand on that?

Nick’s illness really gained force in 1970, when he most needed to do what he could to raise his profile, so I’m wary of reverse-engineering explanations for his lack of success at that time. All aspects of his behavior post-1969 have to be understood as figments of his illness.

That said, whoever you were in that era, to break through as a singer-songwriter, you had to be willing to promote yourself, and he lacked the basic characteristics required to enjoy the challenge of making a name for himself. Gigging was the most obvious way to do that, and it helped if you had the sort of personality that could withstand hecklers, keep an audience amused when you broke a string and also put up with the peripatetic life of a traveling musician. He was too reticent to enjoy engaging with strangers in the manner of, say, John Martyn, but (I repeat!) his illness made him turn ever inwards too.

However, it’s possible that his background had given him a sense of “real” life being less challenging than it is. Certainly, people who’d gone to expensive schools and prestigious universities were anomalous in the pop world, then as now, so maybe he’d been insulated from a few realities, and might have been self-conscious about having a different social background to his musical peers, a “posh” accent and so on. And, of course he always knew he had a comfortable family home and supportive parents to retreat to if he wished, unlike most struggling musicians from less affluent families. But I certainly don’t think he considered himself above the hard work required to succeed; many facets of it just didn’t come naturally or easily to him.

How did writing this book affect you personally?

I found it a very sad and moving process and was greatly touched by how real Nick’s struggles and death still are to his sister and friends. To them he isn’t an “icon,” he’s a very real flesh-and-blood person, and above all that’s what I wanted the reader to feel too at the end of the book.

I was constantly reminded of what a remorseless enemy mental illness is, and how it can strike anyone, anywhere, at any time, and how important it is for us all to look out for each other’s mental health, and not to stigmatize it. Separately, I found it fascinating to speak to such a wide range of intelligent and sensitive individuals about such an interesting era and person. It was a privilege to be trusted with the task, and at the end of it I felt even greater admiration for Nick’s gifts and accomplishments than I had at the outset.