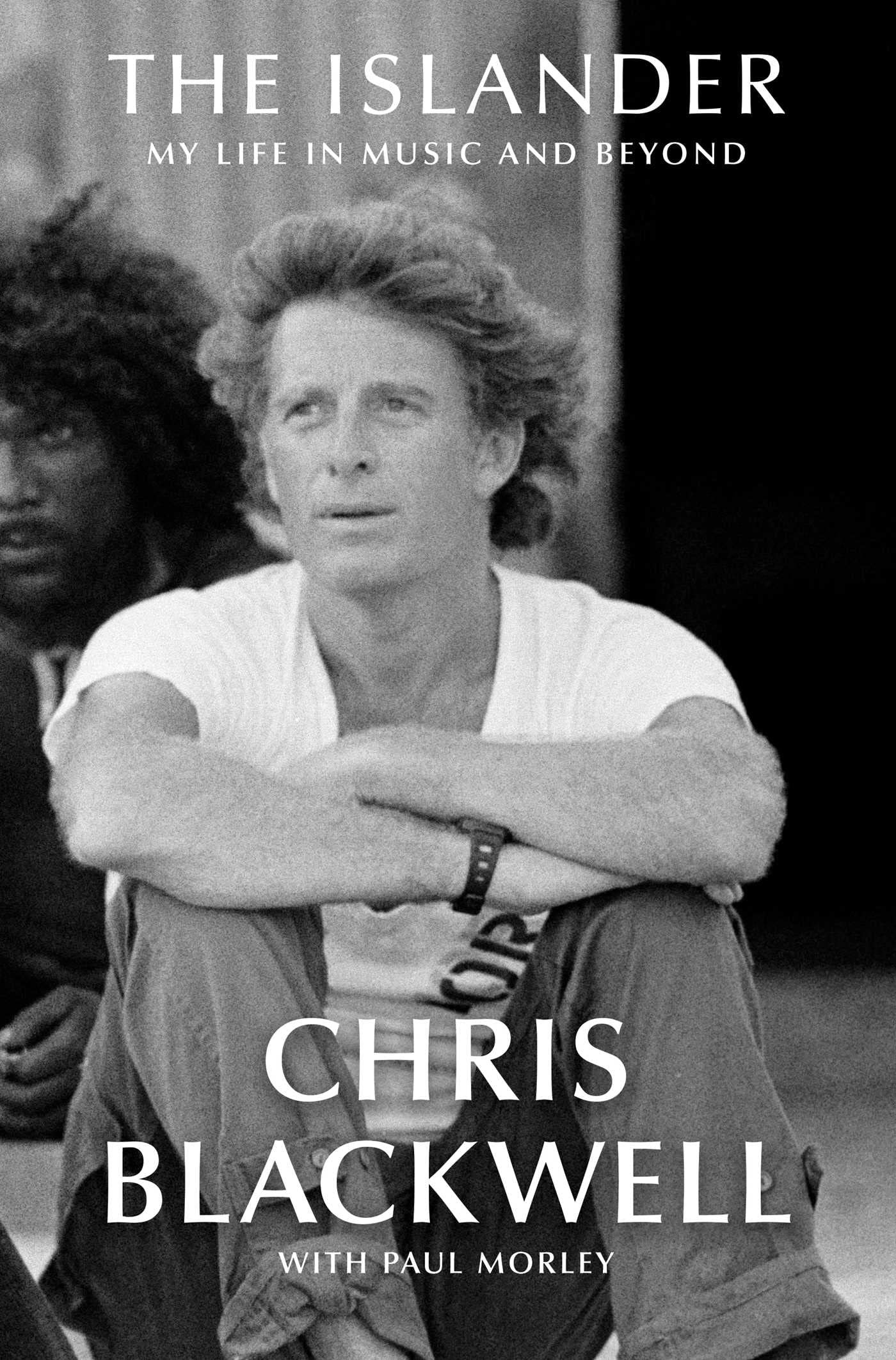

The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond, the newly released Gallery Books memoir from pioneering music executive and Island Records founder Chris Blackwell, would have been an amazing read even if it had stopped before Blackwell discovered a teenage Steve Winwood blowing minds in a London club in 1964, happened upon a struggling Jamaican musician named Bob Marley in the early 1970s or overcame initial doubts about the commercial potential of a nascent Irish rock group named U2 and signed it to a record contract.

Indeed, Blackwell’s early years growing up between Jamaica and London feature one “I can’t believe this really happened” anecdote after another, from being punched by actor Errol Flynn in a jealous rage to befriending James Bond author Ian Fleming and being hired as a production assistant and location scout on 1961’s Dr. No, the first film adaptation of the series that played a key role in introducing the sights and sounds of Jamaica to the wider world. Blackwell was also instrumental in importing American music to Jamaican sound system DJs and parties in the 1960s and later in exporting proto-ska and reggae from the island to listeners around the globe.

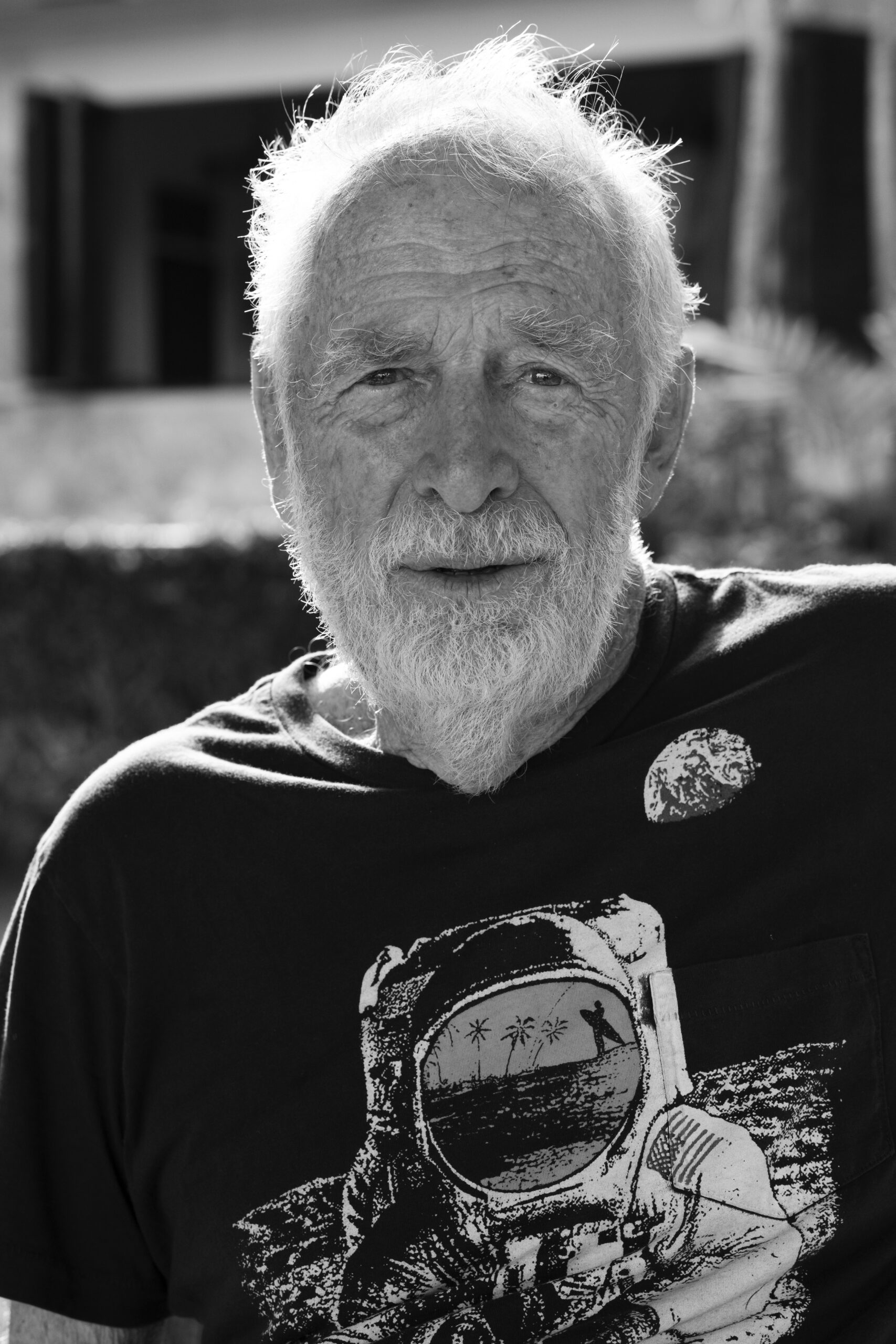

That led Blackwell, who just turned 85, on a lifelong musical odyssey that saw him sign and nurture some of the most legendary names in the field, including Cat Stevens, Joe Cocker, Nick Drake, Grace Jones, The B-52’s, King Crimson, Roxy Music, John Martyn, Traffic, Sparks, The Cranberries and PJ Harvey.

Blackwell chronicles the stories of these artists with humility, wit and insight throughout The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond (June 7), which was co-written with Paul Morley. While many readers will be tempted to jump to Bob Marley- or U2-dominated chapters, doing so would be a disservice to a man who wound up becoming as influential as the acts he discovered. SPIN spoke to Blackwell by Zoom about The Islander, what Bob Marley might have done had he lived past 1981 and the simple pleasures of waking up in Jamaica every morning (at Fleming’s former estate Goldeneye, no less).

SPIN: I had no idea what a huge role you played as a location scout on Dr. No. Was there any part of you that wanted to keep the island more of a secret, or were you enthusiastic about sharing its virtues?

Chris Blackwell: I was excited to do that. It was really at the beginning of something, because this was the first movie of the Ian Fleming James Bond books. Naturally, I was really keen to try and get Jamaica as much attention as I could. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to get any music into it because at that time, I was just starting with it. When I was offered this job, it seemed like such a great experience to have. When they returned back to London, they offered me another job. I listened to a fortune teller, and the fortune teller basically told me I should keep doing what I was doing, which was the music business. That was it. I believed in her. I’ve done some work in films since then and it’s fun and really enjoyable, but you really have to know what you’re doing.

Many people of a certain age only became familiar with Steve Winwood during his ’80s resurgence, but you first encountered him as a teenager when he was tearing up clubs in London with Spencer Davis Group. When did you realize how unique he was?

Well, it was when I first heard him singing. I heard some incredible piano playing, but with a singer singing. When I went upstairs, I found the piano player was playing and Winwood was singing. Not only was he singing, he was belting it out. It sounded like Ray Charles. The keyboard playing was just unbelievable, really. He’s been blessed with unbelievable gifts.

You draw an incredible parallel between Bob Marley and Nick Drake in that in death they are so influential, but during their lifetime, it was a struggle to find their audiences. What do you remember most about Nick?

Nick Drake’s songs were beautiful. His music was so gentle. How he sang them was fantastic. He had a great engineer in the studio as well with him. I never went into the studio with him because it was clear what he was doing. There’s nothing I could have been able to add to what was already there. A close friend of mine, Joe Boyd, who really discovered Nick and introduced him to me, was a brilliant producer. Nick’s music really touches you. It’s got a sort of sadness in it, but a lightness too.

The book relates an experience you had in the studio with Bob Marley in 1980 while he was recording “Redemption Song,” and it was just the two of you in the room. It’s hard to imagine anything more profound, especially in light of what this song now means to so many people.

I’d just arrived from overseas to come and listen to the album he was doing, Uprising. I liked it a lot, particularly “Redemption Song.” It was somewhere in the middle of the record. I said to Bob that I thought he should just do it acoustic — just him playing guitar and singing. I felt the lyrics and message were so important. I just mentioned it briefly, and he said, well, how will that work with the rest of the album, which had the band on it. I said, well, let’s treat it like an epilogue, like the album has been played and instead of the normal four or five seconds after the last track, it’s eight seconds, and it suddenly appears. He said, Okay. It’s weird — we didn’t know when the album was going to be finished, and it also was a period in time when doctors had told him he needed to have his toe amputated. It was a Rasta thing not to cut yourself, and that was it. It was really tragic.

Do you ever let yourself speculate how Bob would have progressed musically throughout the ’80s and beyond?

Yes, for sure. I think he was interested in widening his culture, in a sense, and what his songs were — songs that make you think about things, and not just songs to go and dance to. I think he’d be around today, full of input.

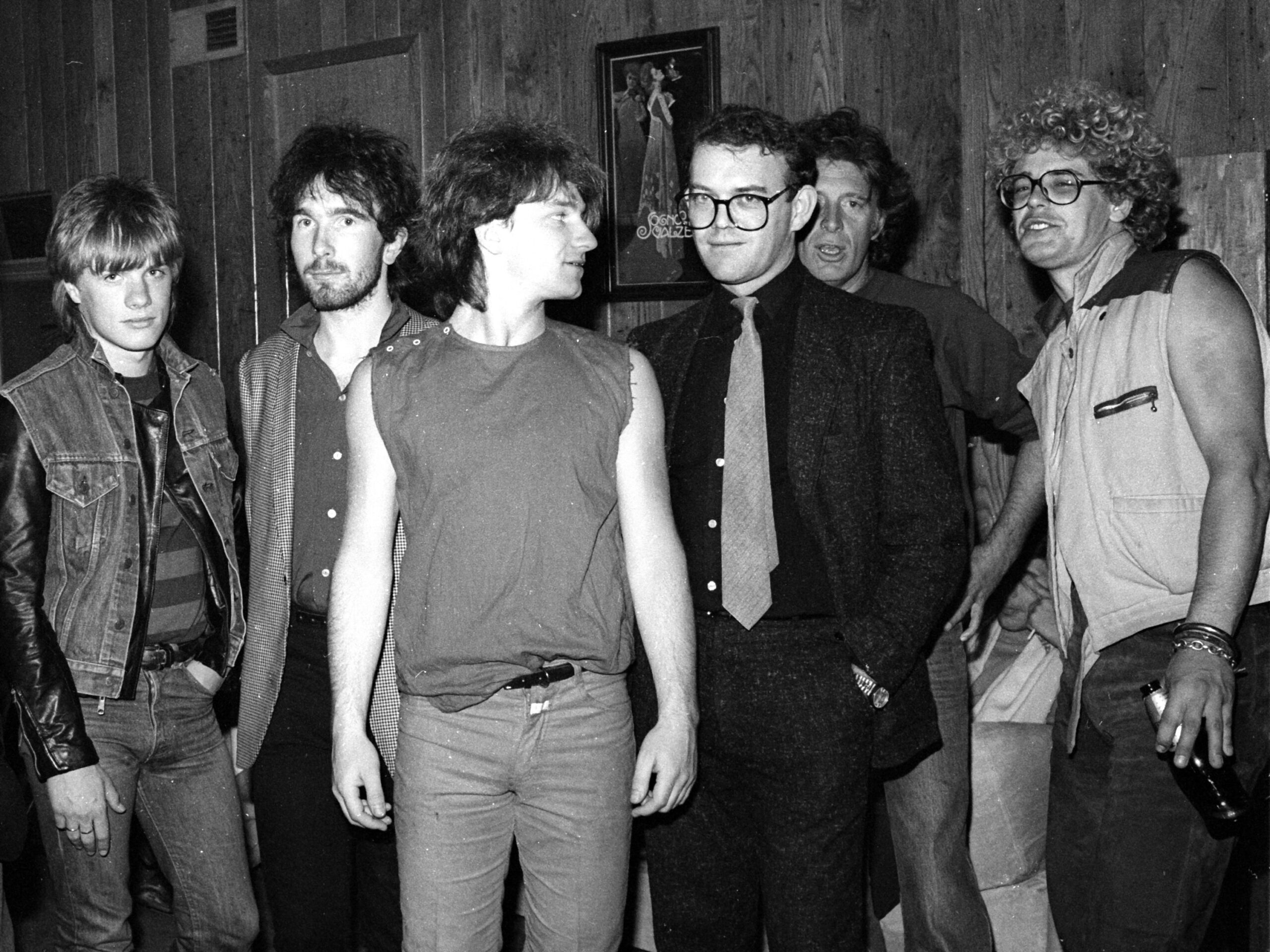

You write that if you’d only evaluated U2 on the basis of their demo tape, you probably would never have signed them. It speaks to the intangibles of a band that you can really only judge with your own eyes. What did U2 possess that set them apart from other bands of this time period?

They projected confidence. Once they got onstage, nobody looked nervous. On top of that, the people they chose to work with were brilliant, like Paul McGuinness. It’s great when something like that happens — a manager who can carry the artist on the trip where they want to go. A good manager and a smart band don’t let themselves get dragged where they don’t want to go. I liked them as people. I didn’t know them well at first, but I liked their energy and their passion for the music.

But you weren’t necessarily on board at first with U2 wanting to work with Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois on The Unforgettable Fire, but in retrospect, clearly they were onto something. How do you walk the tightrope between trusting the artist versus your own intuition?

In general, I was in support of what the artist wanted to do. Surely there’d be something I thought was a good idea, but I thought it could be tweaked into their idea. I may have gotten involved in that a couple of times. I loved music, musicians and musicianship. Whoever it is in the room who has a feel or instinct for what they can really create, I think it’s important that it sees its way through. What would happen sometimes is that a producer would get in the way of something, even though they’d be trying to help.

Was Elton John actually mad at you for 15 years for not offering him a record deal in the early ’70s?

I don’t think he was mad at me at all. The only thing he might have been mad at was having to walk up a staircase in the converted church where I was living. When he got up to the top, he was totally and completely exhausted. We were chatting and I was asking him questions. I loved his music. I met him because he’d sent a song for me to listen to for Joe Cocker. That’s how we connected.

What’s the best part about waking up in the morning at Goldeneye?

Lots of things. I go for a walk, which is very important. A fast walk or a long walk. I come back and get to work. If I’m feeling a bit hungry, I’ll ask for something. It’s a very enjoyable process.