With most of the budget for a young Sinéad O’Connor’s debut album spent in the studio, the emerging Irish singer told her label that what she’d recorded was a pile of fucking shite.

Sinéad felt that the recordings made with producer Mick Glossop were all wrong — disposable ‘80s drivel that was light years from her piercing spirit and vision. And she told Ensign Records (which became owned by Chrysalis during this period) that if they released the work as it was, she would turn her back on it.

By then heavily pregnant and under all kinds of pressure, Sinéad asked young Irish producer Kevin Moloney, who had moved to London a couple years before her, to come in.

And with only funds enough for three weeks in a cheap studio used more often as a rehearsal space, they started from scratch.

Also Read

30 Overlooked 1994 Albums Turning 30

Well, actually, they started with Moloney listening to his fellow south Dubliner about the songs she had long been hearing in her head.

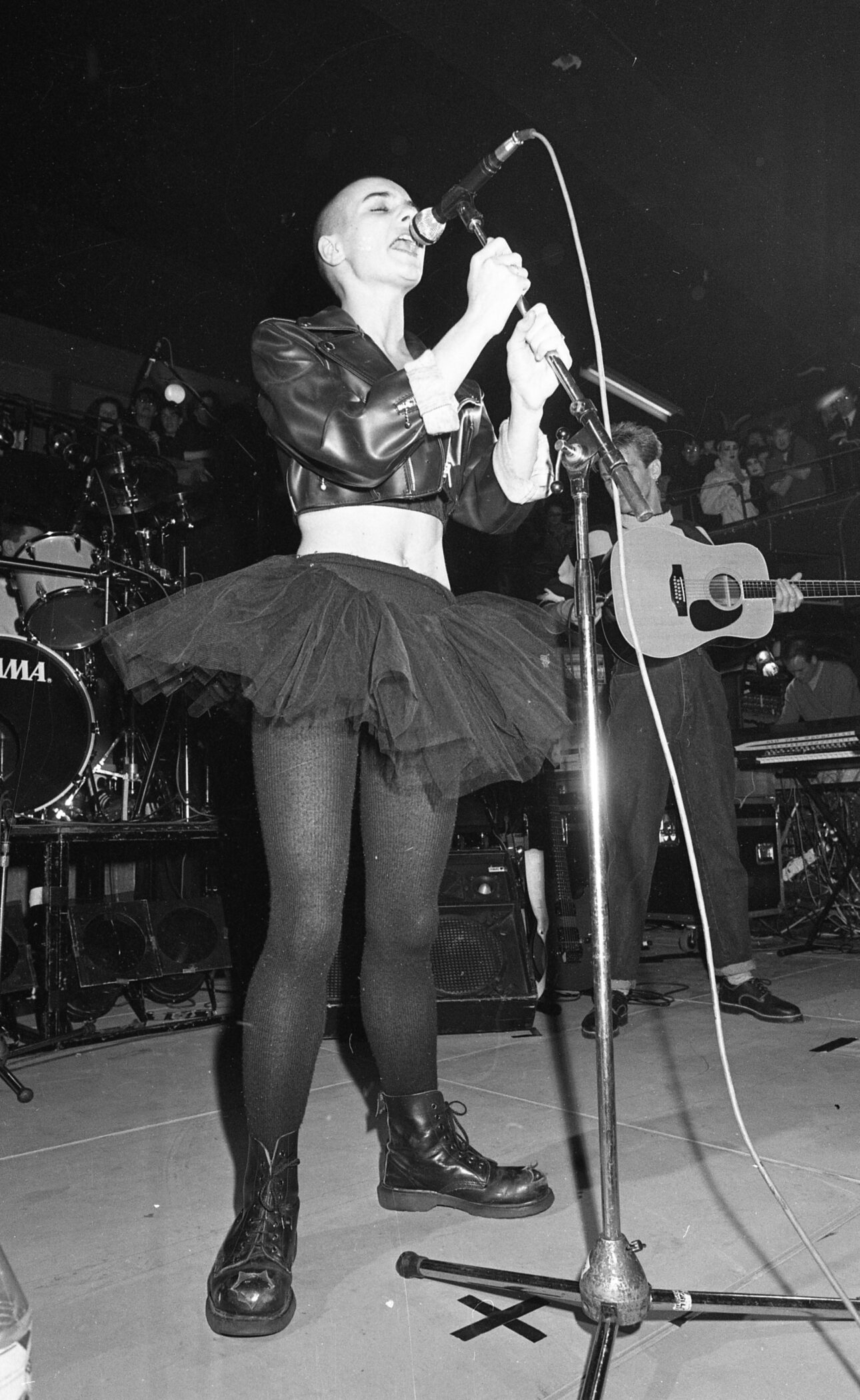

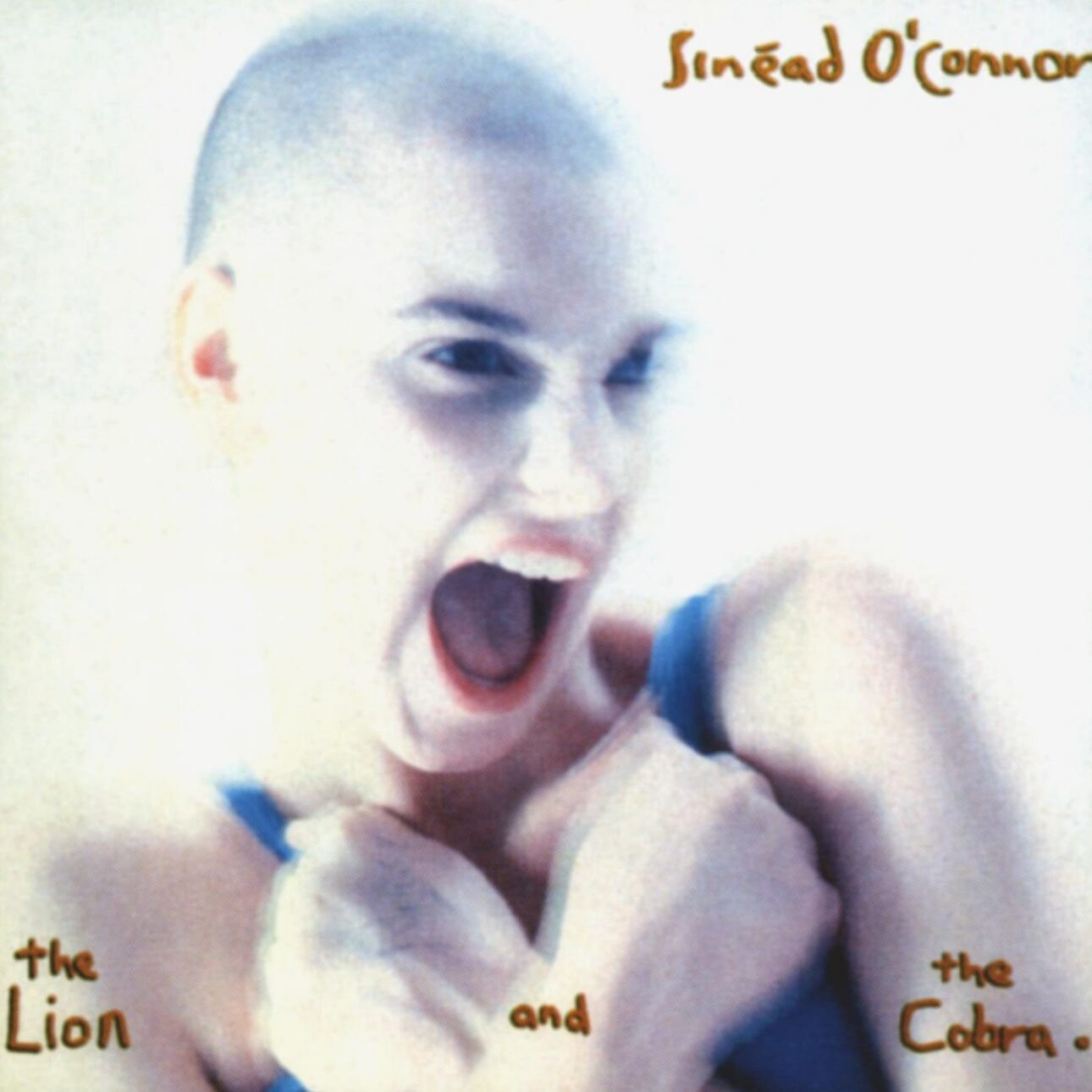

And so was born The Lion and the Cobra (1987).

Almost 40 years later, Moloney, now based in Asheville, North Carolina, talks to SPIN about those history-making weeks.

SPIN: How’d you first meet Sinéad O’Connor?

KEVIN MOLONEY: She was maybe about 18, and I would have been 23 or so. I was an engineer in Dublin, working on a soundtrack with the Edge from U2. This soundtrack is still the only solo project from one of them. It was for a movie called Captive [1986]—originally titled Heroine. The main song [the title track] had been written by Sinéad with the Edge. So one day Sinéad came in with the Edge to lay down the vocals.

What were your impressions of her?

She blew me away in the studio. She was so fucking beautiful and so wonderful with her talent and so giving and so instantaneous with it. It was like, you couldn’t stop her—as soon as she wanted to get something done on the microphone, she fucking went and did it. It wasn’t the usual bunch of takes with everything compiled and composited. She would just do it in a take or two, and then leave it. She’d say, “I’m done.” She’d walk out, it wasn’t like you were stuck not having something—you’d already got the gold. She’d delivered it.

She was such a natural—the most out of all of the vocalists I’ve worked with. She had the most spontaneity, and could release these emotions without working herself up to anything. She could just naturally do it. She didn’t have to spend hours working on something to get herself in the right mood. She had a really natural gift: a gift from the universe.

And at that stage, when she was only 18, she didn’t know she had this. I remember talking to her after that session, going: “You know, you’ve got a big career ahead of you. You can do it.”

She was going, “Ah, no.”

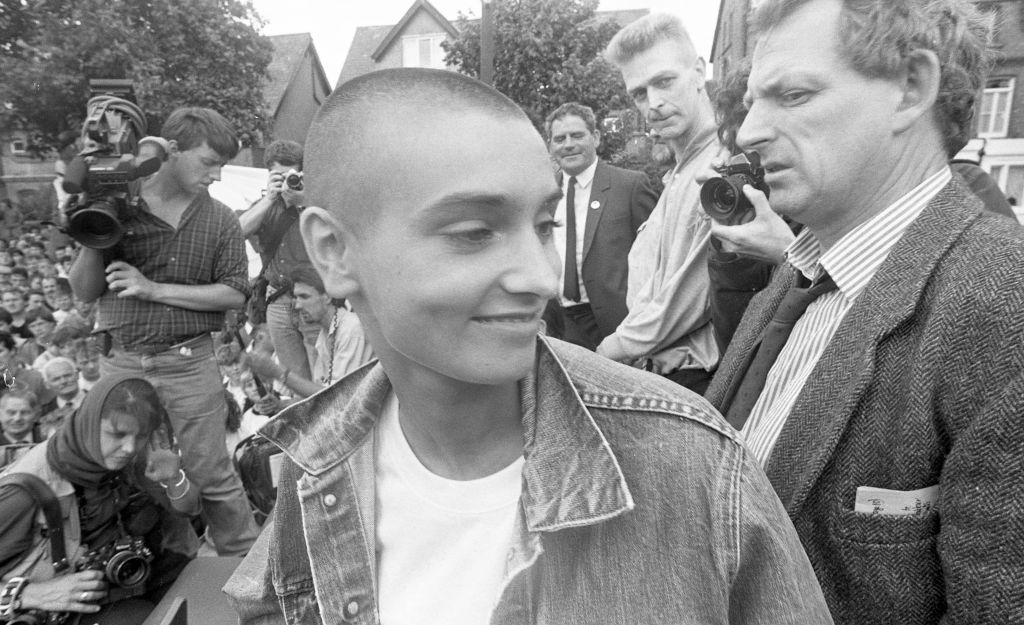

She had a lot of instability in her life. Once I’d known her over the years, I understood why: because of her childhood. She’d been abused, and then she’d gone through children’s homes and was an outcast in a way. She’d kind of raised herself in hellish circumstances. So she was on the outside. She was incredibly tough. I remember her coming into that session with her knee-high Doc Martens, and the ripped jeans before anybody else was wearing them—almost like she was living on the streets, and it turned out she had been living on people’s couches.

How did you come to produce The Lion and the Cobra?

She reached out to me. Her record label wanted her to make a very stylized, pigeonholed, ‘80s glossy kind of pop album. They had mapped it out for her that she was gonna be this successful glamorous chick, and she fucking hated it.

She was 20 or something, and she didn’t know the music business, so she’d followed the guidelines that the record company was giving her—believing that they always knew best. That’s a very Irish attitude: the people in power always know best. And she suddenly realizes [that they don’t] when they’ve got her halfway through making that record—I’m not naming names—with a well-known producer at the time [SPIN: Mick Glossop]. She rebelled. She said, “I think this is a fucking pile of shite. I hate this record. And if you want to put it out this way, I’m not gonna promote it. I’ll just go back and get a day job, and I’ll not be a commercial artist.” And that’s when she shaved her head. She said to her label, “I’m not gonna be your fucking glamor girl. I’m an artist. I wanna fucking make records. It’s not about how I look.”

They came back to her and said, “Okay, you make it the way you’re gonna make it. You’ve got very little budget left, but off you go: make it the way you want to.” And that’s when she contacted me about it. So we made a record from scratch.

Did you hear the scrapped version?

Some of it, but I didn’t really want to hear it, to be honest. Because once she came to me and told me her feelings about what had happened, I just said, “Let’s start again. Let’s fucking rip these songs apart.” Because they’d made lush arrangements for everything, and they all sounded very ‘80s pop, and Sinéad wasn’t that. She had this rebellious, fiery, spunky attitude. She wanted to make the record in her head that she’d been planning on for years.

I think the initial problem with her and this other producer was that she wasn’t communicating what her feelings were about the record. It was like he had taken control of it, and it was his thing. So we started completely from scratch in a pretty cheap London dance studio called Oasis.

But it turned out to be the right place for Sinéad, in terms of the tracking [recording] part. We mixed it in another studio in West London called Eden Studios, but all the tracking was done in Oasis, and it was a rough and rundown place, and the record company never showed up ever.

But it had a great spirit about it: That’s one of the great things about studios. It doesn’t matter how glamorous it is—it’s a matter of how the sound feels in the room when the band are playing. And it had a really good rough sound. Perfect for her.

What did she say she wanted? How did she get across her musical vision?

She wanted it to be close to what she was hearing in her head, and that was a very raw, stripped-down sound based around the lyrics and the vocal delivery. Not about the band. She didn’t want to make a big band record. She wanted to make a singer-songwriter record that had a lot of balls to it.

Was she suggesting what she wanted with the sound and the music?

That would have been myself. We got into a lot of conversations about what it was that was in her head that she was hearing, and how she wanted these things to roll out. It was a creative collaboration between the two of us, because she didn’t understand the recording process. Being only 20 and she’d only been in the studio twice or something, she didn’t understand how things happen. How they end up being what they are. So she was very interested in the whole process of making a record.

She would make pots of tea for everybody—make sandwiches—just being one of the guys. She wasn’t trying to be all, “I’m the star. I’m the fucking record label’s next prodigy.” She was just trying to be one of the regular people. Which is really good.

I’m glad I’d had that first experience with her working with the Edge because I kind of knew her a bit. And it turned out she came from the same suburb of Dublin as I did—Glenageary in south Dublin—and she’d gone to the girls’ convent school next door to the boys’ Catholic school I went to. So she had the nuns on one side of the wall, and I had the Catholic priests on the other side of the wall. And we’d been using the same trains and buses going to school.

Anything distinctive about the area you two are from?

It’s beside the ocean. And you can get out into the countryside in five, 10 minutes, or you used to be able to. It’s part of Dublin City, but beside the ocean and a lot of nature. I think that created a lot of sense of longingness for her. She was—she is—a traveling spirit, and I know she’s out there in the universe still.

Sinéad was more than a little pregnant during the Lion and the Cobra recording sessions, wasn’t she?

All those vocals were done when she was in the later stages of pregnancy, and every day that she’d come in she was on fucking fire. She gave birth about three weeks after we finished.

Now that I’ve been around pregnant women five times, I understand what it’s like. The hormonal levels change rapidly as they go through the cycle of it all. And that was what was going on. Sinéad didn’t know this. I didn’t know it at the time. So it’s like every day was a new thing.

Some day she’d come in and go, “You know that thing that we did yesterday and I really loved it? Today, I don’t like it. Would you just erase it, please.”

I think we did that once, and then after that, I learned, don’t ever erase anything, because the next day she’d come back in and say, “Hey, remember I asked you to erase that thing? I hope you didn’t do that.”

After the first time around I said, “No, I didn’t do it, Sinéad. It’s still there. You got it. Don’t worry about it.”

She was firing on all cylinders all the time, and to me there’s more passion in those vocals than I think she ever did afterwards. There was a raw quality to them. She never talked to me about her childhood at that stage, but that’s what was going on. She was in all this pure emotion that she’d carried with her all through her life, and she let out in her lyrics.

A lot of them are about her mother, and a lot of them are about her upbringing and the horrific nightmares that she went through. I think she’d been writing them since she was a teenager, in the homes that she went through, you know? She’d been an artist in the making for quite a while. She just didn’t realize it.

And when we did the album, she was only about 20. Looking back on that record, it’s an incredible accomplishment for somebody of that age. And it still stands up.

I’ve been listening to it again these last couple of weeks. I was hooked on it when it came out. It’s still highly distinctive and powerful, and a very unusual bunch of songs.

It really was at the time because no other females were doing it like that. She broke a lot of ground for people in doing what she did with this record. You know, she wasn’t doing the pop thing—she was an anti-pop artist.

She was a freaking firecracker, so beautifully creative and such a natural spirit, you know? She wouldn’t hold her words back—she’d just talk it straight. She was so freaking ballsy, it was unbelievable.

What was London like at the time you and Sinéad were working together? Loads of Irish there in the mid-‘80s?

Oh, Jesus, yeah. London was still the mecca for Irish people. And there was a lot of anti-Irish feeling in the U.K. because of all the I.R.A. bomb threats and stuff that was going on.

I remember a lot of times trying to get to our studio, but you couldn’t get there on the Tube because it was shut down from bomb threats. So you’d have to get there some other way. That was the mid-’80s in London. There was a lot of feeling that Irish citizens in the U.K. were third class citizens. There was a lot of agro about it, and if Sinéad had that spunky attitude and a lot of people had to stop her from getting into fights. Just because somebody said the wrong thing about the Irish. She would just explode, you know, but she was heavily pregnant, so not a lot of people wanted to hit a pregnant lassie.

How did you expect her album to do? Did you think it would be a niche thing, or that it would be big?

We had the feeling at the time that she was doing something really unique. I did the first five albums with U2 as an engineer, and when I worked on their very first album, Boy, that felt similar. The feeling when we were making Boy was it was so raw and so different to anything else that was going on at the time. I did that album when I was like 18 or something, and Bono was 18 and, you know, Larry was maybe 16 or 17. So everybody was teenagers on the first album. Sinéad’s album reminded me of that sense of the voyage: that this is unique, this is very special, and nobody else is gonna do anything else like this.

And how did the release go?

The label didn’t quite know what to do.

“Mandinka” was the obvious single, but a radio station in the Netherlands started playing “Troy,” which was about seven minutes long. And it was unheard of for radio stations to be playing something so long back at that stage. Maybe in the ‘70s they were, but in the mid-‘80s they were all playing four-minute pop songs—it was Kylie Minogue and all fucking teeny bop whatever. That was it. So it took off with “Troy” in Europe, and that’s when the label realized that this is really different. They were like, “Wow, people are responding to something that’s so epic.This is really special.” If people are listening to a seven-minute song on the radio and digging it, they knew that they had something really unique, and they pushed it.

How did news of her death hit you?

I was just devastated this summer with her loss. It took me a long time to come out of that black hole.

She’s five years younger than I am, so there’s no way somebody that young should be passing away. Such a beautiful gifted talent that the world doesn’t have any longer.

But she’s left us these beautiful recordings. There’s a lot there for young artists to aspire to.

I know she’s out there in the universe still. She’s a traveling spirit who was sent on a mission. And she did a lot. She did a lot by tearing up the Pope’s pictures. That was wonderful. I know her record company and everybody hated her for doing it, but she needed to do it, and she did the right thing. That was a very important statement that she made.

She would take on anybody, and it wouldn’t fuck her if if it was the Pope or the President or anybody. It wouldn’t bother her. Everyone was the same for her.

If anything, she reminds me of Joan of Arc. She has that kind of spirit and fire about her.

See Kevin Moloney and his Instagram

Read about rock’s Jeanne d’Arc, the late Sinéad O’Connor (December 8, 1966 to July 26, 2023) being SPIN‘s Artist of the Year this year—now—here.