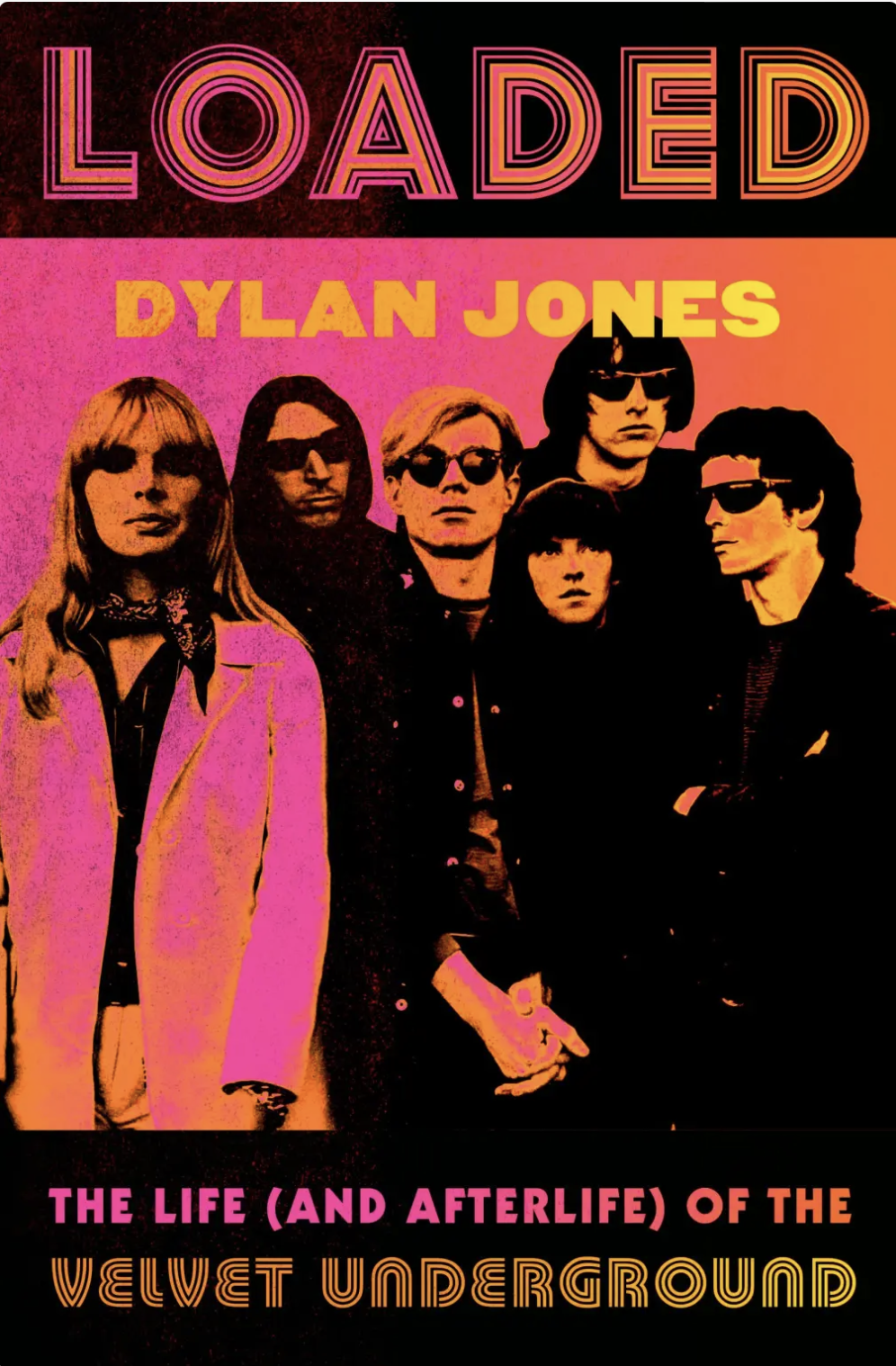

In the new oral history Loaded: The Life (And Afterlife) of the Velvet Underground, veteran culture journalist Dylan Jones gives us swirls of vivid eyewitness reports, provocative opinions and clashing viewpoints.

That’s fitting for a band made up of notoriously flinty characters — Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Maureen Tucker, as well as their patron Andy Warhol and Nico, the singer he imposed on them — that rose through the volcanic scene of Andy Warhol’s Factory in the flashy late-‘60s New York. The result helped spark the explosions of London’s glam and both that city’s and New York’s punk furnaces.

It’s a cast of hundreds — the dramatis personae roster at the beginning of the book runs for nine full pages, two-thirds from interviews Jones did himself. They’re all there: the rock stars (David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Iggy Pop, Jimmy Page), the Warhol “Superstars” (Edie Sedgwick, Holly Woodlawn, Billy Name, a particularly trenchant Mary Woronov). But as or even more important are the people who saw the Velvets outside of the spotlight, the family and friends with their own angles.

Jones has written and edited more than 25 books (including a David Bowie oral history), and is currently editor-in-chief of the Evening Standard, having served in the past as editor of the UK edition of GQ and other major publications. In 2012 he received an OBE from Queen Elizabeth for his service to publishing and fashion.

He only met Lou Reed once, near the end of his life in 2013, while producing an awards show in London. But Reed and the Velvets played a crucial role in his life, and while the book comprehensively covers a sweep of time from 1960 to the present, it’s also a very personal story for the author, as he told SPIN in a video chat from London.

SPIN: Where did your relationship with the Velvet Underground start?

Dylan Jones: I was 12 years old [in 1972]. And you are very receptive to alien forces at that time. And David Bowie was my alien force. And for us at that age, David Bowie was like Google. If David Bowie says, “I like Iggy Pop and the Velvet Underground,” we’re like, “What the fuck? Let’s go check out those guys.”

Go back to that first moment of discovery. What was the first song you heard?

It was a greatest hits album, a double album which had a cover which was meant to approximate an Andy Warhol Velvet Underground cover. It had lips and Coca-Cola bottles on it. The first song was “I’m Waiting for the Man.” In fact, When I was writing the book, “I’m Waiting for the Man” — it is one of those records that previously would come on the radio and you’d turn it off. It’s like, “I’ve heard this 10,000 times. I don’t need to hear it again.” And I succeeded in getting myself back to a place where I could imagine I’d never heard this record before. And I think it’s quite a difficult thing to do. Maybe I’m conning myself that I achieved it. But I think I did. To try to listen to that record through fresh ears, it’s quite an amazing thing because you hear it now, it’s that song, we all know that. But try to imagine what that was like when it came out of nowhere and everything else that was around it, the context. It’s mind-blowing. The orchestration, the lyrics, the production, the sound, the noise, the level, et cetera, et cetera. Mental. Crazy. Mental bonkers!

There’s been so much told about the Velvet Underground, about the Factory, about New York of that time and London of that time. What was the biggest surprise for you in putting this book together? What changed your view?

There are two things. It’s really difficult, but really important, to try to put yourself in a place before things have happened. I tried to paint a picture of what New York was like in the early ‘60s, before everything happened, before there was an explosion of pop culture, before the music, before the art, before fashion, where New York in the early ‘60s was just like New York in the late ‘50s.

And the second thing I think is in my exploration of Lou Reed’s persona, which was an incredibly strong persona, one of the defining personas of rock ‘n roll. But it was manufactured in the same way that David Bowie was, that Jagger was. The most successful pop stars, their public persona is an amplified version of what they’re really like. I still think most people don’t understand that. Bruce Springsteen is an amplified version of Bruce Springsteen. Jagger is. Keith Richard is. The same way Lou Reed is. I really drilled down into that.

You have a bit with a journalist who had been promised that Lou was going to be good in an interview, not be surly. And when it came time for it, he wasn’t good.

Exactly. That was Anita Sarko, who’s a friend of mine. He couldn’t help himself. He said, “I turned into Lou Reed.”

You have a lot of big names here, but also a lot of lesser-knowns and unknowns.

There are people that you expect to speak to. They’re the tent poles. Then there’s another group of people which deserves as much airtime, whose experiences are important, just as important as the bold-faced names — photographers or journalists or hairdressers or boyfriends or girlfriends or people they went on holiday with or dry cleaners or whoever. And then there is the third type, where someone says, “Have you spoken with Kevin?” And you go, “No. Who’s Kevin?” There are a lot of Kevins in my book.

Who were some of the key Kevins?

Just a wide variety of different people who don’t usually get the airtime. People like Duncan Hannah, the artist, whose contribution to the book is extraordinary. And that’s another aspect that’s unlike every other book that I’ve done — there were lots of people I needed to speak to who are of a certain age. There was an element of catching these people before they passed on. And Duncan was one of those people.

He came to my house 18 months ago and I interviewed him. We sat around the kitchen table and he went back to New York and two weeks later he was dead. It was terribly sad, but it’s an illustration of what I was talking about, the kind of symptomatic nature of writing a book about people who were still alive, but who were perhaps reaching the end of their lives.

How many of the people here would you call reliable narrators?

It doesn’t matter. That’s part of the joy. And actually, if I can interview four people about one party and they all give me completely different interpretations of what happened, who’s to say they’re not all right?

You have that one where illustrator Robert Risko says Warhol’s death changed everything in New York, and right after that you’ve got photographer Bob Gruen saying it didn’t change anything at all.

I love that. And it’s not done for contrary reasons or to be cute. There’s a legitimacy to it, but I think it’s really illuminating as well, because people’s perceptions of things are completely individual.

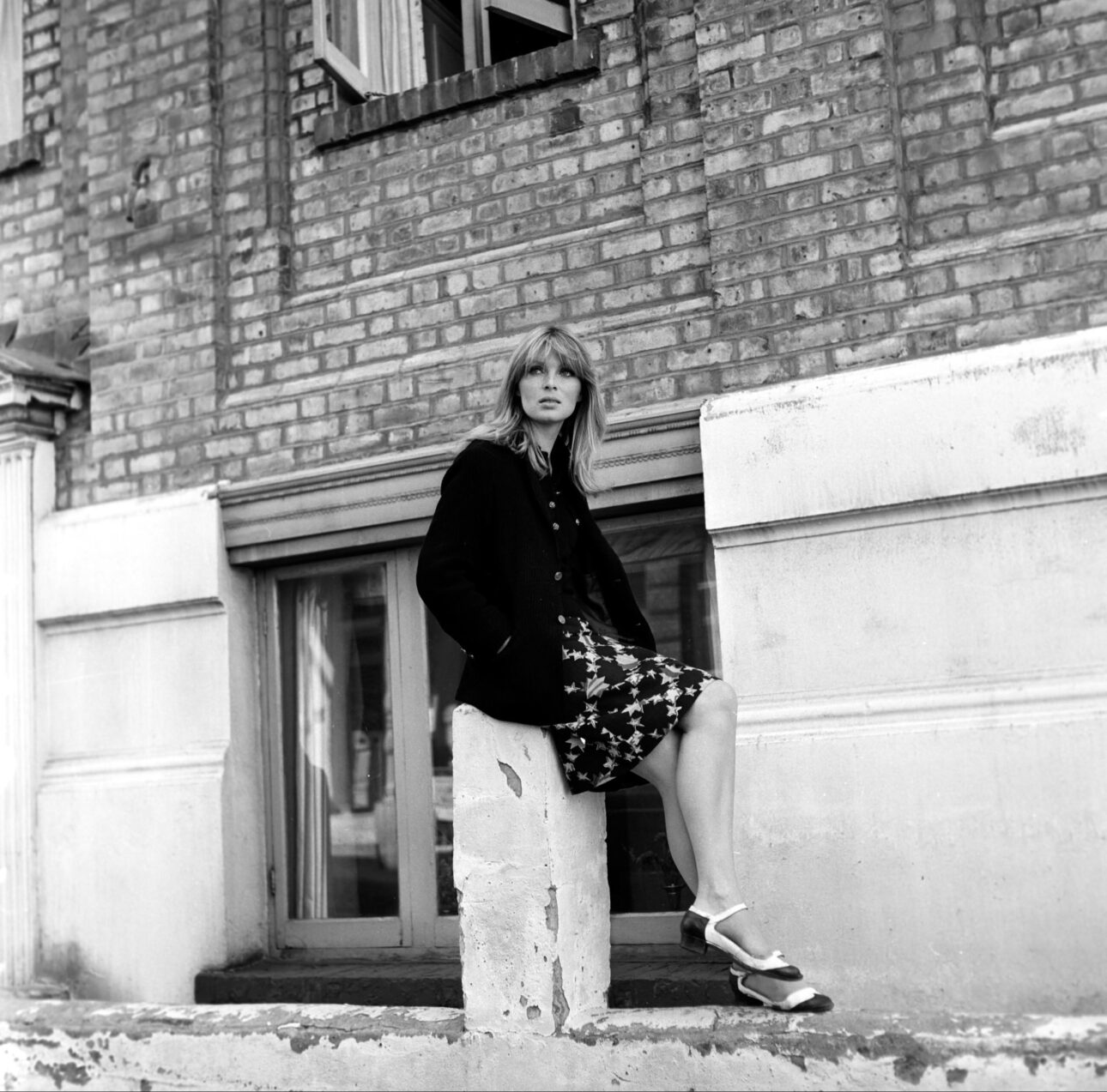

One of the stars of the book is Mary Woronov with such comments as her remark regarding Nico having a son with French actor Alain Delon: “It was cheap to have a child with a famous actor. Alain Delon? That’s cheap.”

She was great. It was one of the joys about doing that, meeting people like that, meeting people who were so important to a particular time. And Mary was interesting because she understood her importance, but it hadn’t defined her. The saddest thing is when you meet someone who had five minutes of notoriety and they’ve traded off it for the rest of their lives. Mary certainly hasn’t. But [some of] these people flew high and they were starbursts and a lot of them had unpleasant landings. What a heady world, what a heady time. How amazing.

Who felt like the hardest to get, that when they came through you knew it was really important, key to the story?

There are a couple of people in the book, I won’t mention who they are, but people who knew Lou toward the very end, who were with him in the last couple of months before he died and people who were with him when he died. It’s impossible to overestimate the importance of their testimony, which is very powerful, but very affectionate. I found what they said very affecting, very moving, actually.

Plus there were some people who had, how should we say, contact with Lou when he was at his drug peak in the mid-‘70s in downtown New York. And they’re just great rock ’n roll stories. I mean the sex, the drugs – it’s just fantastic. It’s great to be able to tell a rock ’n roll story and still be shocked.

Did you find there were people who only wanted to talk about Reed?

Not at all. In fact, after a while I gave up talking about him, because you can have enough. I actually went back to where John Cale was born, where he was brought up, which isn’t too far from where I live in Wales. And his story is more remarkable than Lou Reed’s, because here was a bog from a working-class background, Welsh, in the middle of nowhere I suppose you’d call it Buttfuck, Arizona. He gets a scholarship to go to New York to study classical music, gets involved with the avant-garde quite quickly, and in five minutes becomes one of the architects for one of the most formative rock groups of all time. That’s a pretty weird narrative arc.

In many ways you’re showing the sweep of time and how attitudes have changed. Obviously, Lou Reed figures into that, for one thing in his sexuality. What do you think the general perception of that is now?

I think because of his long relationship with Laurie Anderson, and because we know more about him now than we did, but when he died I think people probably look upon his sexuality as a narrative, as someone who was sexually curious, was dynamically bisexual, and ended up in a very satisfactory, cozy relationship with a woman. But again, I think sexual fluidity contributed enormously to his art and his success as a performer.