Spring 1974: David Bowie enters the RCA office in Manhattan to produce a couple of tracks for Lulu, the Scottish singer coming off the success of the James Bond theme song, “The Man With the Golden Gun,” and yet it is a chance meeting with someone else there that day that changes the direction of rock. David Bowie is meeting someone who will become his most trusted musical collaborator and facilitator, the man who guides him into Black American music and culture.

Guitarist Carlos Alomar has recently signed a contract at RCA as a session musician. This is a huge career step for a 23 year-old who has been gigging as a professional musician since his mid-teens. Alomar has never heard of Bowie, but producing Lulu sounds like a pretty big deal. Bowie is unfamiliar with Alomar’s work; he likes what he hears and they get along well.

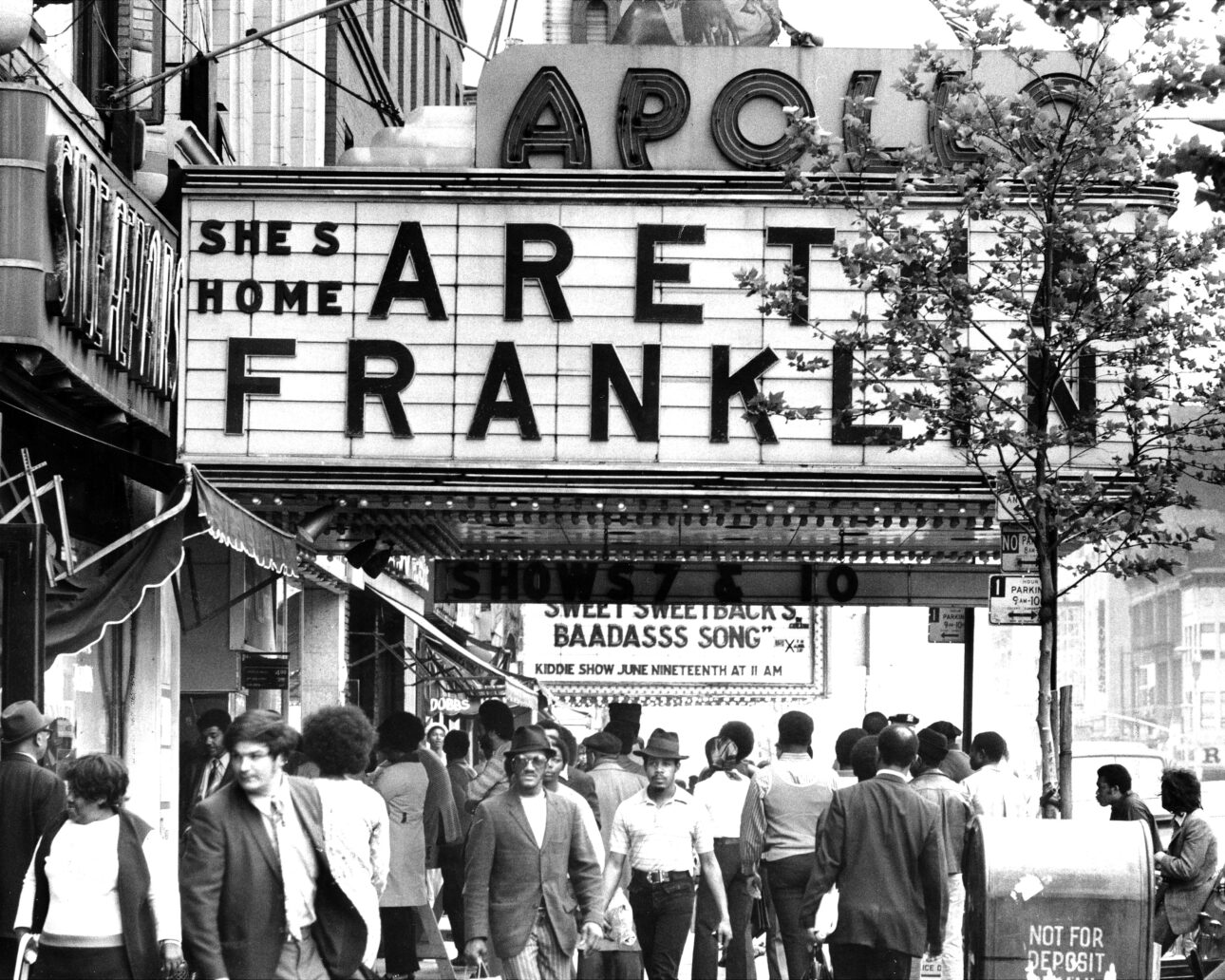

That night Alomar brings Bowie home for a home-cooked meal of chicken and rice by his wife, singer Robin Clark. At his apartment Alomar plays Jimi Hendrix songs on the guitar for Bowie to show that he can rock. Bowie asks Alomar—as did Paul McCartney before him—for stories all about the Chitlin’ Circuit of touring and performing Black music across America. Alomar is happy to regale and educate. This leads to hangout sessions with Alomar taking Bowie around New York, to places in Harlem like the Apollo Theater, Sylvia’s Soul Food, and other clubs and bars, in hunt of authenticity and the Black experience.

Bowie at this point is riding high on rock and roll stardom. He is in the process of working his way out of the Ziggy Stardust persona and preparing for a tour in support of his forthcoming LP, Diamond Dogs (released May 1974), an album that tries to extend his glam rock era. It is to be his biggest and most theatrical tour to date—more Broadway spectacular than rock show. Bowie asks Alomar to join the Diamond Dogs tour, but when his management reaches out to Alomar, they wouldn’t pay his rate that others were already paying. Not one to compromise, Alomar rejects the offer. This is the first time he turns Bowie down.

In August, Bowie tries again, calling Alomar to ask him to go to Philadelphia with him to record a foray into Black American soul music. Alomar says yes, and other than the session musicians he books, he also brings along for support his childhood friend and former bandmate, Luther Vandross (who has not yet broken through to fame as a soloist), as well as another former bandmate: his wife. Bowie wants to record at the legendary Sigma Sound Studios, the home of producers Gamble and Huff and their Philadelphia International Records with backing band International Philadelphia Allstars. This is the nexus around which “The Sound of Philadelphia” is being crafted, a soul sound with lush strings and funky rhythms. However, neither Gamble nor Huff, nor any of their regular musicians or production crew, are available. Bowie has none of the Philadelphia musicians who drew him to this town, sound, and studio, but he has Carlos Alomar.

Bowie has no idea how lucky he is.

There are additional sessions for Young Americans after the Diamond Dogs tour, and Bowie calls Alomar back. This time they record in New York at the Record Plant (December 1974) and at Electric Ladyland (January 1975), both with John Lennon. Alomar shares a writing credit with Bowie and Lennon on the song “Fame” as he developed the main riff. It is at these sessions that Alomar works for the first time with drummer Dennis Davis.

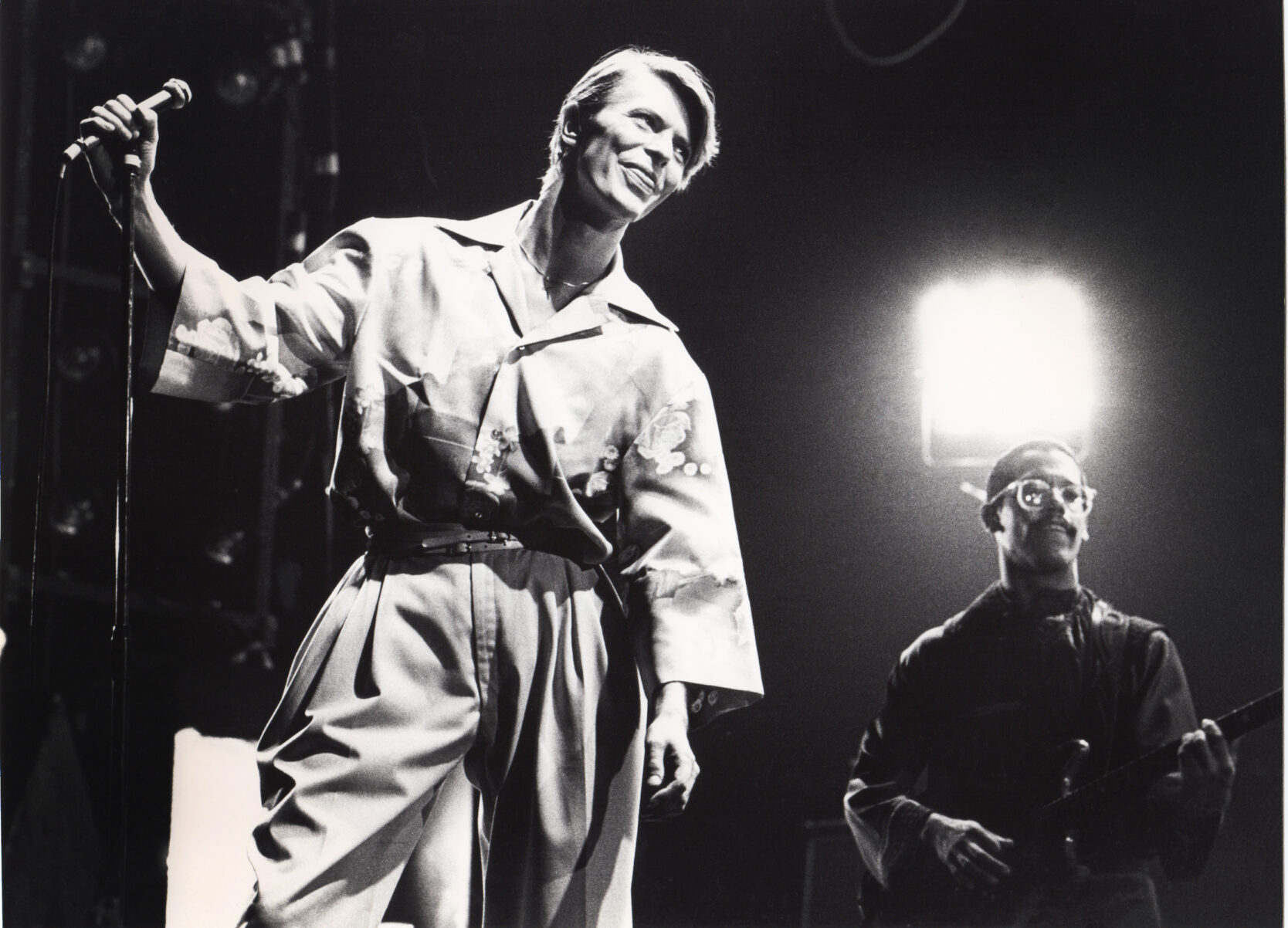

After this foray into Black American music, or ‘plastic soul,’ as Bowie called his efforts, the Englishman next goes on to write and record Station to Station (1975). For this dark and wonderfully strange transitional album, he calls Alomar back who comes out to Los Angeles and plays on the whole album. The song “Stay” is a shared writing credit between Bowie and Alomar marking a funky collaboration of the duo. For the subsequent Station to Station tour, the role of Alomar in Bowie Industries expands to that of bandleader and arranger. The tour covers North America and Europe, and helps to free Bowie from a dark period in Los Angeles, and nurtures a renewed interest in Europe, specifically Cold War Berlin.

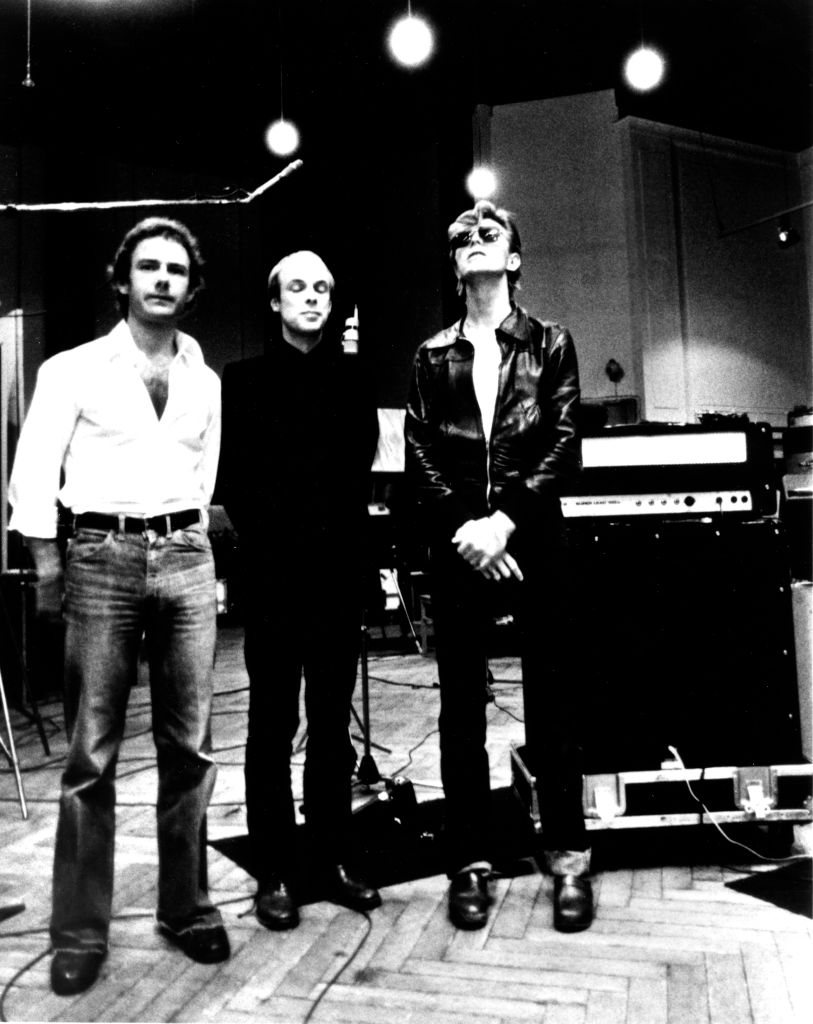

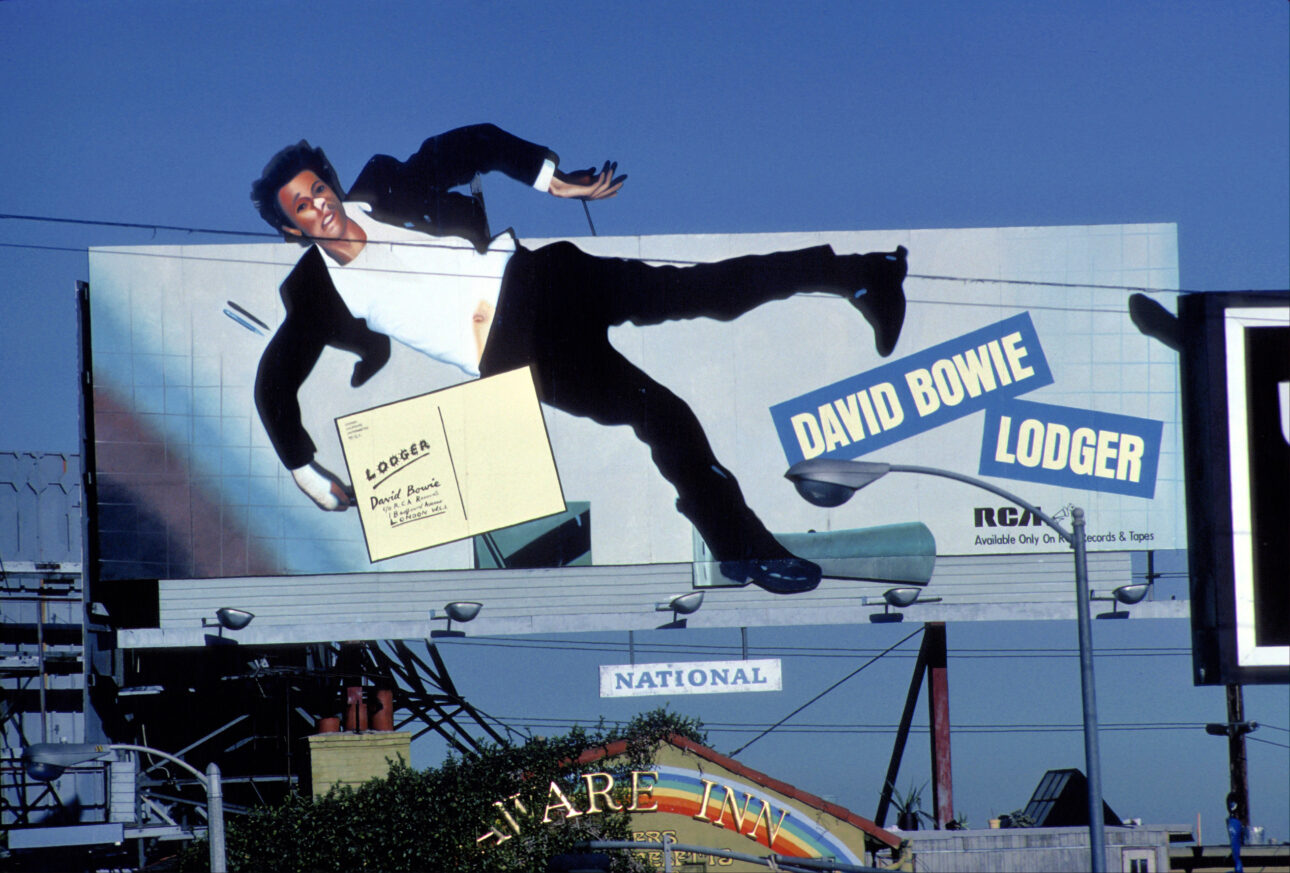

Starting in January 1977 with Low and extending across “Heroes” (1977) and Lodger (1978) is what music history and legend refer to as David Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy. The three albums are produced in collaboration with experimental, ambient musician (and former Roxy Music synth player) Brian Eno. For three albums experimenting with European Romanticism, modernist avant-gardism, internationalism, and new technologies Bowie brings along Alomar, as well as Dennis Davis on drums and George Murray on bass.

The three albums of the Berlin Trilogy become seminal and striking works of modern music, with Philip Glass eventually composing and conducting a trio of symphonies based on each album. David Bowie’s Berlin Years period is seen as one of the most unique and creative periods of any modern musician’s biography.

That’s the basic history. Today, I’m waiting for Alomar at the horseshoe bar in the center of Red Rooster Harlem on 125th Street when he calls to let me know he found a parking spot. All of the various images, across the albums, tours, and decades come back to me of Carlos Alomar with different stages of facial hair and afros of different heights; costumes and stage-presence following Bowie’s or his own personal aesthetic.

It is 45 years since Bowie, with Alomar and the others, began recording the album, Lodger, closing The Berlin Trilogy (Bowie himself referred to it as a triptych). The Berlin Years are a legendarily raucous and weirdly geo-political time in rock folklore. A large portion of Steve Erickson’s 2012 novel, These Dreams of You, stoked the myth of this strange and wildly creative period in Bowie’s body of work. The factor most often emphasized behind the creativity is the presence of Brian Eno. Low (1977), the first album of the so-called trilogy, marks the first time that Eno—by that point a pioneering solo artist of experimental and ambient sound incorporated into rock and pop—works with David Bowie.

Alomar presents as a hip, stylish retiree or grandfather on vacation, living his best life. His graying hair is cropped low at the sides with tight black curls on top. At my age (the same age as his daughter, acclaimed singer Lea Lorien), our rapport makes him feel paternal, and yet still sagacious, and he embraces this role. He’s a teacher, a bandleader, a father, and he speaks with rhetorical flourishes, wisdom, and authority.

Throwing his mind back to that original fated meeting with Bowie at RCA, Alomar casts it in a different light and from a different angle than most biographies written by devotees of the Thin White Duke.

Bowie needed me more than I needed him.

Carlos Alomar

Carlos Alomar: I look at the trilogy in a different way. We’re [here] in Harlem, celebrating the actual birth of what it is that I did, and how I got here and how Bowie and I met. But all my training began right here [in Harlem].

Over there at the Apollo Theater, right at the door, man you might see two or three cats hanging out. “Hey Nile Rogers, how you doing?” “Dennis Davis. How you doing?” I know these cats. And so, these are the guys that are gonna steal your gig the minute you turn around. So, there’s this camaraderie that we grew up [with]; we knew the people that were around here.

So, let’s take that and let’s look at what happened with David Bowie. David Bowie did not just meet Carlos Alomar. David Bowie met Black.

And because he met Black, everything that was Black came all from Carlos Alomar.

Why? I happened to be right in the middle of Black. I worked at the Apollo Theater. So we must go back to the very beginning, and that whole thing is very evident.

We also know that David Bowie had the Spider from Mars. What a goddamn, fabulous, fucking brand. Who’s the bass player? I don’t know. Who’s the lead guitar player. Oh, that [Mick] Ronson guy. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

But what you do remember is the brand: the Spiders from Mars.

How many records did they do? Maybe two. Whatever it is, everybody [who served the band] has a different notion as to what their involvement was. But they do know this: David Bowie killed them all. Dropped them, and just said, “Bye.”

And [after] all that glitzy glamor nonsense he comes to America, and what he does is he hooks up with this guy: Carlos. Just: “Carlos.” That’s what he said in the interview [when Bowie was asked who his new collaborator was.] What’s his name? “Carlos. He’s this Black guy. He’s really good […] I wanna work with him.”

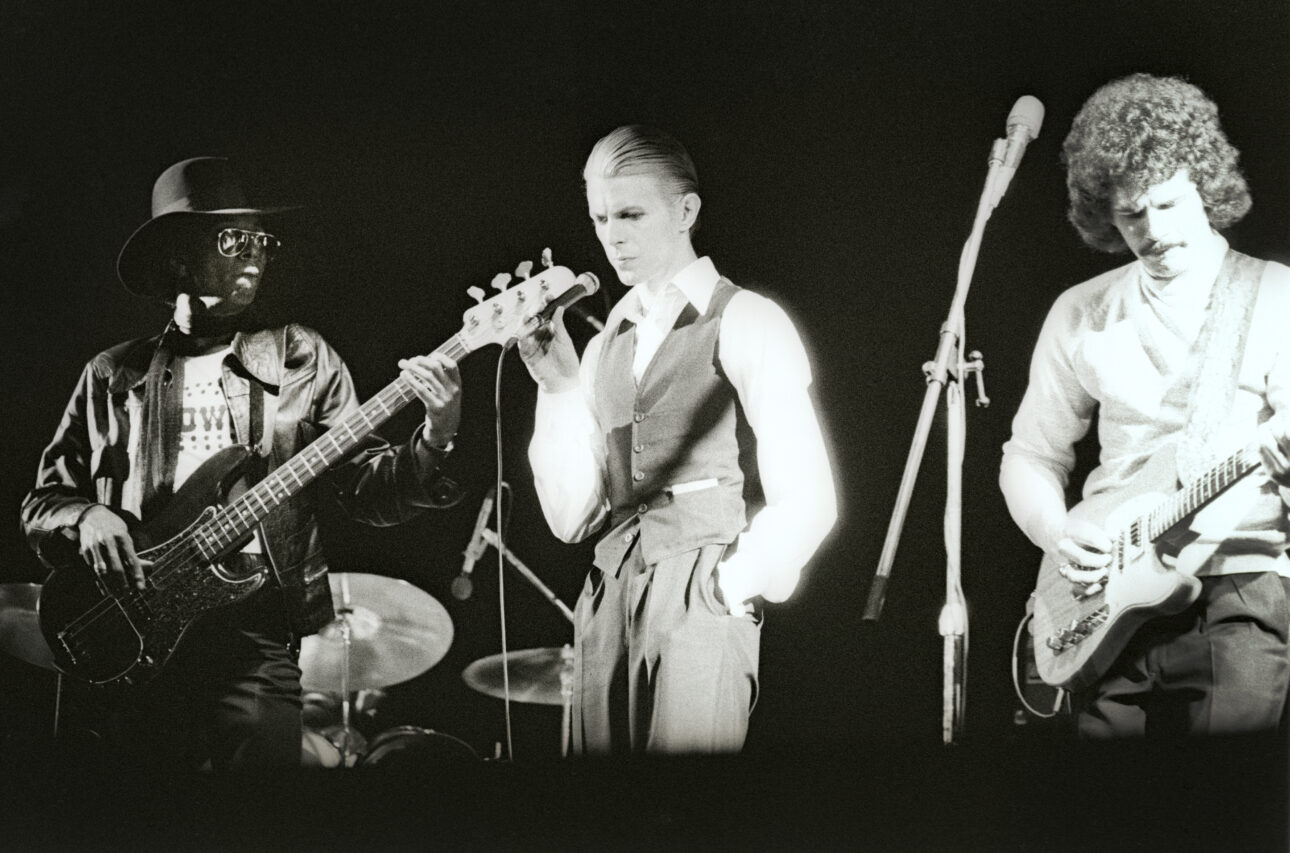

I’m Puerto Rican. And when everything fell apart, and he couldn’t get The Sound of Philadelphia to do his Young Americans album, he got Carlos Alomar, and who did Carlos Alomar bring? His bass player, Emir Kassan, and his drummer, Dennis Davis. We had all these people: Luther Vandross, Robin Clark, Anthony Hinton, Diane Sumler, all of them, and created the Young Americans album.

But then something happened.

He called us back, and nobody was there. Just me. And the drummer that I did “Fame” with: Dennis Davis—I was working jazz gigs with him. Then they called the last guy, George Murray. Now we got ourselves the trio.

David says he wants to work with me now on Station to Station. I’m like, “Dude, here’s the deal: I don’t work with piano players.” Not that I don’t work with piano players; it’s just that piano players have 10 fingers, and they wanna use every finger. And when they play a chord, they don’t just play a C chord. They play a C with an add-nine and maybe a major seven. And then leading them with all those leading tones force the singer to sing. So, I told a boy from the beginning, I don’t do that, man. I need the holes. Why? When I was working with James Brown, you know man, they created those holes in those pockets. And the first thing they slapped me down with when I overplayed was, “Yo man don’t disturb the groove.” The rhythm section has to lock down hard.

In this moment, I don’t want to talk about Carlos Alomar ’cause Carlos Alomar didn’t do it all by himself. He made the arrangements, but somebody had to execute. Who executed them? They’re called the D.A.M. Trio [Davis Alomar Murray]. That’s what I want you to brand.

Okay.

It’s not an issue of just Carlos Alomar, because look, if I didn’t have Dennis Davis, Carlos Alomar, and George Murray—the D.A.M. Trio—this would never have worked.

So, here you have David Bowie killing off the Spiders from Mars. And he hooks up with a three-piece Black rhythm section. I’m Puerto Rican, but I’m still Black. Got it? That happens for all these years: eight albums but nobody mentions them—“Who are those three Black guys?”—Nobody says anything.

Know what they say? “Oh, look at Eno; look at [Robert] Fripp.”

My daughter was like, ‘You gotta get on the website thing.’ And so, I decided, let me write a little story about the making of the D.A.M. Trio. And that’s when I actually introduced this brand.

That D.A.M. Trio would be with David Bowie from Station to Station, throughout the trilogy, and then finally, Scary Monsters. I would return later on for more, but the Trio was over by then, and anyway the issue of creating a brand finally allowed us to be acknowledged as a formidable part of the creative process of David Bowie.

So, although I speak to David, I’m the medium or the muse behind the trio being able to execute. Execute what? Man, execute break time; execute flipping the beat; execute Latin grooves; execute clave beats; African rhythms. And electronic and technologically viable equipment that later on would be like, damn! I created the first 19-inch rack units for stage use. Dennis Davis was playing through these funnel drum sets that he had created out of fiberglass. So we were always on the edge of technology as well.

So, the issue of Carlos Alomar sometimes has to be looked upon as though I’m an arranger. That’s the difference between me and a lot of other people. When he [Bowie] has tours, I gotta rearrange all the songs so that they sound current. Even if they don’t have horns, they got horns now. If they don’t have strings, they got strings now.

That’s easy—but getting a rhythm section to be able to play and create the holes that then Brian Eno can think in? And can [Robert] Fripp fill up all that? And Ricky Gardner and all the other guitar players that he calls—what they get are these perfect tracks of the rhythm section locking it down. Now whatever you wanna add to that, you can’t mess it up.

That also allowed me to play a few tricks on the audience. Little did they know that “Stay” on Station to Station was “John I’m Only Dancing.” David says, “Make me an arrangement,” and then the minute I make an arrangement he changes the words. Well then that’s a new song and it’s all well-hidden. Nobody can tell. Take a song and take the chords, flip ’em over backwards. Listen to “Move On,” and it becomes “All the Young Dudes.”

There’s all these tricks that you play, but unless the rhythm section can execute these weird-ass ideas, it doesn’t work. And so that’s what happened when we did the trilogy with Brian Eno and all that, and even Iggy Pop. David Bowie brought in the D.A.M. Trio to do Iggy Pop’s career as well [SPIN: the trio plays on The Idiot, 1977]. So, the trio became David Bowie’s viable instrument of destruction when it came to reforming himself and transforming music as a whole.

So, I want to give the props to the D.A.M. Trio. And maybe you know that Dennis Davis passed away. And I just got together with George Murray. So I kind of wanted to make sure that the D.A.M. Trio’s legacy is intact and bound to mine. Because I can’t take the credit. I can take credit for certain things but let’s face it, it’s like giving Mick Ronson credit for the whole Spiders from Mars and never acknowledging the bass player and the drummer. I mean, that’s crazy. We should set the record straight.

I think Hugo Wilken does that well in his short book on Low for the 33 ⅓ series. He presents the three of you as this core unit of sanity. Anyway, musician and music photographer Chris McKay said he doesn’t see the Berlin Trilogy as a trilogy because it’s the same band as the albums before and after—like what you’re saying. So, since you guys play on Station to Station, the Berlin Trilogy, and Scary Monsters, what sets the Trilogy apart from the one before and the one after? Anything?

The Macintosh computer had just come out [the Apple Computer 1 was released in 1976], and David is like, “Let’s do symphonic music with computers.”

And he said, “Why doesn’t anybody play the B-side?” Remember in those days, the A-side had the singles—that’s what everybody wanted to hear. He [Bowie] decided nobody listened to the B-side, so “Let’s do this experimental stuff that I’ve been talking to Brian Eno about and put it on the B-side, and screw you record company. You’re not gonna promote the B side anyway.”

Why call it a trilogy? Well, you’re exactly right—some of those songs don’t really merit experimental stuff. And the amount of experimentation towards the end was hardly any [SPIN: the final album of the Trilogy, 1979’s Lodger, still features Eno but, unlike Low and “Heroes,” is filled with conventional songs rather than having an ambient B side]. But it does mean that the involvement of Brian Eno is what makes it a proper trilogy.

But let’s not be silly about the obvious. Dude, it’s called marketing. Why sell one when you can sell the trio? Everybody does it. It shows an astute business brain, which David had. Why not sell it as a three-part series?

And only “Heroes” was recorded in Berlin.

Oh yeah. They scattered it around. I think the Chateau [Chateau d’Héroville outside Paris], you know, Hansa in Berlin, and Mountain in Switzerland. So, we had a few places that we went to.

We had to develop a different methodology. That methodology was introduced sometimes by myself, sometimes by David, and sometimes by Eno.

Eno was more particular, because he had those strategic cards, and they kind of offset a mind block that you might have by eliminating the perception of what’s needed, not what’s wanted. You know what I want, I wanna put down the best thing I got—[but] that’s not what’s needed, man. What’s needed is this drone that just plays one note: blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. It’s monotonous, but it’s what’s needed.

What I wanna do is impress you. Dude, don’t impress me. Just play what I want, you know?

And so these different methodologies really created a different creative process for us. We had to think before we plucked. Nobody thinks before they pluck because muscle memory kicks in and we play the same old way we played before. You can’t do that when you’re too busy pondering. What the hell—did that card just say, “Hey, you just came back from the war.” What the hell has that got to do with the part that I gotta come up with? Well, it’s got a lot to do. I did that when we did “Breaking Glass,” and you’re going to hear this one guitar part. I’m just hitting one note for the whole thing. Angry, mad, frustrated. Why? I just came back from the war, and I can’t get a gig.

That was in the Oblique Strategies card deck? You came back from the war?

Yeah, one card said, “You just came back from the war,” and then another one said, “You’re a farmer.” Something like that. And when I thought about “I’m a farmer,” I developed a part like you water a seed. You start out with a little thing, and then the second verse: you water it, and it develops into the second thing, and then you water it some more. And then […] oh my god, what the hell did that just blossom into? The cards allow you to do something that we’ve heard of and we forgot. Don’t think—ponder.

So you were born in Puerto Rico in 1951. And when did you come to the mainland?

How the hell should I know? I was a kid. Around three or four.

And you moved to Spanish Harlem initially?

Yeah. Proudly.

When did you pick up the guitar? How old you were?

Ten years old. It was my brother’s. I used to steal into his room: touch his guitar. That would’ve been all right, but I also played his records. I went up there and played his record—and scratched on his records. That’s when I got called into my dad’s room. He told me, “Look, if you stay outta your brother’s room, I’ll give you the guitar, because he doesn’t play it anyway.” I was like, hell yeah. I still went in his room, but I got the guitar.

Then I had to play church.

My father was a Pentecostal minister. And so the hidden obligation: “You wanna play guitar, son? Good, take your little butt over there and play guitar when everybody comes in and sings their little hymn.” So, I knew my three chords: G, C, and D. No matter what you sang, I played G, C, and D.

Then he took me to get a Mel Bay Guitar Dictionary and on the cover it said something like 2,200 chords. Dude, I knew three. I bought that book. Now in church, I was playing every chord they had.

That’s when I realized the power of a chord. I learned how to play a seventh chord—it’s kind of like that rock and roll, that Bo Diddley, that funky sound. That seventh chord got me put in discipline, because, “You’re not supposed to be shaking your butt when you’re in church, Carlos. That’s the devil’s music. Carlos, you’re bringing the devil’s music into the church.”

I’m like, “What the hell are you talking about? I’m a teenager. I just learned how to play this guitar and I got 1200 chords and I’m gonna unleash them on all of you.”

How did you wind up at the Apollo Theater?

By the time I was 15, I was already playing in bands. Luther Vandross recruited me to be his first band leader when I met him at Fordham University’s Upward Bound program. We were college preppies—underprivileged kids taken from high schools and given these opportunities—and during the summer they gave us extra tutorial. We stayed in the dormitories at Fordham University in the Bronx. That’s when I met Luther: when I was in high school.

He wanted to come down here to the Apollo Theater to audition. He said, “Why don’t you come with me for moral support?”

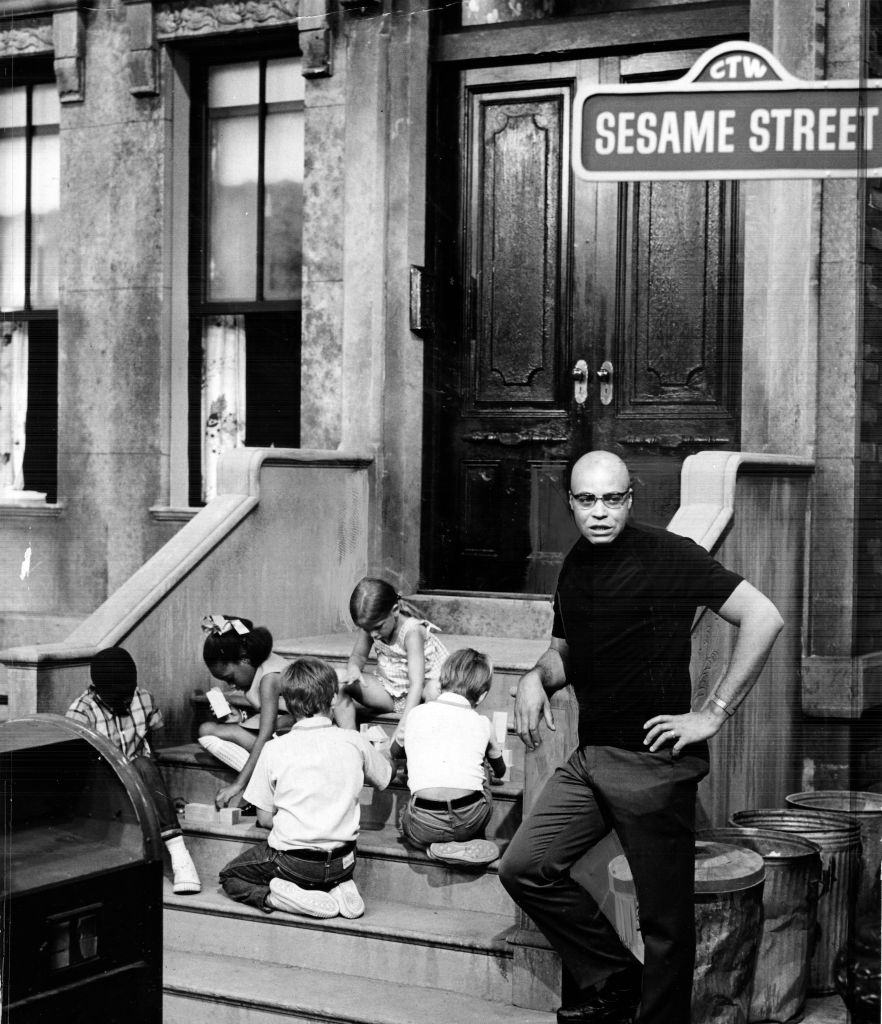

Well, he got into Listen My Brother [a musical ensemble noted for its performances on Sesame Street] and after about the second or third time of me accompanying him down there, the director comes to me and says, “Boy, what do you do?”

Respectfully, I said, “I play guitar, sir.”

He said, “I don’t wanna see your face down here no more until you bring me that guitar. Show me what you can do.”

So I came back. Oh my God. Here I am on 125th Street on the train with a Sears and Roebuck guitar and a Sears and Roebuck amplifier that my father had bought me a year ago. He had passed [died] the year back. So, I was kind of like, on my own. He gave me his blessing to be a guitarist. That’s why I was at the Apollo Theater. Man, I got down there and I could hear them laughing in their hands at my Sears and Roebuck equipment. But I put it down, I plugged it in my guitar, and I played “Soul Finger” and they applaud. And I got into that band. That’s how I joined Listen My Brother at the Apollo Theater.

What year was that?

1966, around there.

So, the band was put together by the Apollo Theater?

Yes, they auditioned people and… have you ever seen Fame?

Of course.

It was like that. They teach you dancing. Hell, they sent us to the Rock Day Dancing School to learn African dance. I couldn’t even do salsa.

We have to frame it around the fact that around 1964 we had the Harlem Riots. Some cop shot a kid and sparked off this whole gigantic thing. Around 1965 everything kind of was settling back into place. So the Apollo Theater having this group of kids was very important for them.

I was raised at the Apollo Theater. I’m in the basement. We learn choreography downstairs. And then the director says, “For homework, I want you to go upstairs and watch this group called The Temptations, and watch their dance steps. Microphone technique. Go upstairs, and watch this performance by Nancy Wilson and the way she meanders and saunters down that stage. And watch how she commands the whole audience.” I saw Michael Jackson and the Jackson Five when they were kids.

We did the pilot for Sesame Street. Jim Henson came down to the basement of the Apollo Theater and saw our review and said, “Y’all are the perfect people to write new songs for this show called Sesame Street.” He wanted to be representing the youth of America. And look: when you look at Sesame Street, that’s Harlem. Those are the Harlem tenement buildings. And all the little Puerto Rican kids and the Chinese kids and American kids, and the blonde and the black hair, all of ’em were on Sesame Street. Yeah. And so we were the opening act, and we were on the pilot, and then we did songs for Sesame Street.

We were the first act on the first shows of Sesame Street, the pilot and such.

When they went on the road, they asked me if I wanted to go on tour. I was like, yeah… The first tour I ever did. First job that I took a plane. They were going to Hawaii. I took that gig, man. The first tour of Sesame Street. We went to California, Hawaii.

So keeping kids off the streets, giving them music… And then Sesame Street.

Yeah, so that’s what Listen My Brother was.

This is where you met Robin Clarke, who would become your wife, in the band?

Luther introduced me to Robin. When I saw Robin for the first time, I went to see her. I think it was at City Center. She was singing behind Mahalia Jackson, and I was like “Oh shit, I know who Mahalia Jackson is, but who is that fine young girl behind her? Ooh hoo.” And there she was. I married her two years later.

So, did this feel like what ultimately became the Young Americans band? Did that band feel like an extension of Listen My Brother?

No, it [Young Americans] was a recording session. What you have to remember is we’re not a band. We are recording session musicians. We create. We are creatives. A band is “Here’s the record, learn it,” or “You’re a band member—you’re all I’ve got.” That’s a different situation.

When it came to band-leading and doing the arranging on tours, do the musicians use sheets? Are they looking at sheets when they are playing?

Well, it is a very delicate situation ’cause I don’t like to intimidate the musicians, and so I really try to make it so that I’m the buffer between David [and them]. That way they don’t have to go to David for anything. And so I have to look at every musician, and treat them like, “Hey man, I want you to play it like you wrote it. Not play it like that guy wrote it. I don’t want you to be Fripp. I want you to be you. I want you to think like Fripp, but you can’t play like Fripp. So just think about what you would do if you were at the session.”

You know, I’m not a stickler for cover bands. You know, you gotta sound exactly like the record and stuff. I’m like, “Are you kidding me?” I don’t worry about that stuff. Plus, what I try to do is revamp every song. Let’s say we are doing “Let’s Dance.” It has horns. So now I gotta do an arrangement for “Ziggy Stardust,” but it’s gonna have horns in it. They are not just gonna stand around waiting for the “Let’s Dance” to play horns. And now you have a new generation that just heard Ziggy Stardust with horns. Dude, they think that song always had horns. So, you introduce an old song to a new audience based on the new arrangement that accommodates the new mode of music. You have to be a little bit, you know, thoughtful about what it is that you’re presenting. And with David planning the choreography, the set list: man, that was serious.

Since Bowie has all that going on, does he give you freedom and trust you to do the arrangements?

He says, “Blah, blah, blah.” He leaves the room. He doesn’t come back until I call him and say, “Here’s one from column A, two from column B: what do you want?” You see, people might think that one thing is a verse, and the other thing’s a chorus. We don’t think like that. We just do two parts and watch what happens when I make this a chorus and make that the progression. And then he listens to it, and he goes, “Oh, much better.” It’s like a Chinese menu. Pick one from each column. That kind of freedom. We love that. And not only can we do it, we can modify it, flip it. You know, we’re not a one trick pony—the D.A.M. Trio could do anything.

In David Buckley’s book, Strange Fascination, he mentions that when you joined the Diamond Dogs tour mid-way through, Earl Slick—who was the tour’s lead guitar player—was worried you were there to take his job. Your response was great, you said, “I play down on this part of the guitar; he plays up at that part.”

Yeah, I’m here to do my job, not his.

Intimidation is an easy part, because everybody feels that they don’t have another job. And this is a very important part of musicianship: they don’t owe you shit.

David Bowie had me do Young Americans, but I turned them down twice. I finally did it. Thank you very much, then I went on to record two other albums by somebody else. I wasn’t even thinking about him.

Then he calls me back for the next time: “I want you to go on the tour with me.”

You’re gonna have to pay me a lot of money for that. I just got into RCA—I’m the session musician. You know where David found me to do Station to Station? I was on Broadway with Tim Curry and Meatloaf playing The Rocky Horror Picture Show. On Broadway. Do you really think I needed to stop doing that to go with David Bowie? I didn’t need it.

But you know what? I did [join Bowie]. A lot of musicians get mad ’cause you didn’t call them back. Like you are their lifeblood, you know. That is going to lead to a lot of resentments. Nobody owes you nothing, and that’s how you create gratitude. Be grateful for what you got, and then move on.

So, how did it happen that Niles Rogers, once your understudy at the Apollo, produced the Let’s Dance album (1983), and yet you were still brought on to be the bandleader for the tour?

Well, David Bowie wanted to work with Nile Rogers ’cause he wanted a hit, and he knew that he would give it to him. And I was ready to work with him, and I was anxious for us to work together. What came in the way was, David Bowie had a new management company, and they wouldn’t pay me what I wanted. They were, “You’re a side man, and now Rogers is the producer. Now Rogers is playing with the guitar.”

I’m like, “Look man, if I play one note, I get the same amount that if I play a million notes—it doesn’t matter. The actual fact is you’re not playing for my notes, you’re playing for my name. And the minute my name goes on that record, give me my money.”

They wouldn’t do it. So I pass on the record.

When the record is done, now they gotta go on tour. David Bowie tells them: “Call Carlos.”

The minute they call me, before I even talk about a tour, “You know that money that I asked you for—for the album? I want that money as a signing bonus.”

I got the money to do the album, [but] I never did the album.

When you fuck with Carlos and the money, then Carlos simply says, “Have a nice life, and the answer is no.”

The most powerful word in the English language is ‘no’.

Carlos Alomar

How do you feel about the authenticity of Bowie singing American Black music?

It’s a fucking song, man. What’s the deal?

So, if I write a song about love, I was really in love? I was really hurt? No. I look out the window, I see a circumstance, I’m a writer. And I can say it better than you. And when I say it, I said it in a way that touched your heart because you felt it. And that’s authentic. because I was able to tap into what your needs are and what you suffered. And when I explained it, I voiced it in a way that you couldn’t. And when you heard it properly it touched you in the way that you wanted to be touched. And those tears, you could never have stopped those tears if you wanted to. You can’t. The human condition allows that to happen because there’s an integral part of your soul that you can’t control. See a movie, and for some unknown reason, you start crying like a baby. What trigger did that thing push in you that created that flood of tears that you can’t see to acknowledge? The human condition holds a lot of stuff.

What does the future hold for you?

A trilogy tour. The D.A.M. Trio Trilogy. And this way when you hear the D.A.M. Trio songs, minus all the slow, ambient Eno stuff, you’re gonna realize we didn’t do a Brian Eno album. We did a D.A.M. Trio album. And the D.A.M. Trio album has got all the songs that you forgot about. This is the D.A.M. Trio at its strongest. Take away all the slow stuff. Take all the symphonic stuff, and then listen to those albums. That’s the D.A.M. Trio.

If the story isn’t about the D.A.M. Trio, then how can you go make it just about Eno? I’m not trying to go Black and white on you, but if I told them right now that I got a tour that I’m gonna put together with Brian Eno and Robert Fripp, you know how much money they would give me for that fucking tour? But if I tell them that I’m going out to do the D.A.M. Trio tour they wouldn’t give me the time of day. That’s the reality. That’s the story. You want to know about the Trilogy—don’t mention Brian Eno, and then we’ll have a conversation.

That was the biggest moment that the D.A.M. Trio had only to be overshadowed by Robert Fripp and Brian Eno. Why? Because they are white and British?